Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between bladder trabeculation, urinary function, and the stage of pelvic organ prolapse (POP). The medical records of 104 patients with POP who underwent cystoscopies and urodynamic studies were reviewed retrospectively. Age, incidence of detrusor instability, stage and site of POP, and the parameters of urodynamic studies of patients with and without bladder trabeculation were compared. The difference in the incidence of bladder trabeculation was estimated between patients with and without a suspected bladder outlet obstruction. There were significant differences in the patients' age, stage of POP, and maximal voiding velocity. Patients with a suspected bladder outlet obstruction had a significantly higher incidence of bladder trabeculation. In addition, patients with advanced stages of POP were also found to have a higher incidence of bladder trabeculation.

Bladder trabeculation, which is detected by a cystoscope, is the secondary result of a bladder outlet obstruction and is known to be caused by morphological and histological changes due to hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the bladder muscle and the infiltration of the connective tissue, as confirmed through animal testing.1-4 Some studies have suggested that bladder trabeculation is generated by the aging process. However, a principal pathological mechanism was reported to be connected with changes of the bladder muscle in order to compensate for the increased urethral resistance in the lower bladder, which is caused by physiological or anatomical reasons such as a bladder outlet obstruction. The degree of the obstruction differs according to the site or degree of hypertrophy. Increased total volume of the prostate can mechanically accompany the obstruction of the lower urinary tract and result in an increase of intravesical pressure (Pdet) and a decrease of the maximal voiding velocity (Qmax) in the urodynamic study.5-7

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) was first reported in 15218 with a vaginal hysterectomy. According to a 1963 study in Switzerland, the incidence of POP was 30.8% in women between 20 and 59 years old, and the study reported an 11.1% risk of undergoing surgical treatment for this disease in women up to 80 years old.9 POP is generated by the weakening of the support tissue of the urethra, bladder, and pelvis, which is caused by dysfunction of the fibromuscular tissue that fixes the pelvic structure to the pelvic cavity.10 POP is related to delivery injury, neurosis, pelvic surgery, estrogen deficiency, constipation, chronic cough, myopathy, connective tissue disorder, etc.11-14 Dysfunction of the bladder, urethra, or prolapsed organ can be associated with the anatomical reason that the female genitals are located close to the lower urinary tract, colon, and rectum. POP can induce the symptoms related to organ function, urination, bowel movement, sexual life, and local symptoms caused by the prolapsed organ. The local symptoms related to urination are exemplified by urinary incontinence, frequency, nocturia, urgency, residual urine, etc.15 POP is known to be related to urinary tract obstruction, which causes recurrent urinary tract infection and hydronephrosis, in addition to disturbances of urination.11

In the male population, there is a high prevalence of prostatic hypertrophy and, consequently, acute dysuria, which are both capable of inducing urinary obstruction. Subsequently, numerous studies have made progress in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with prostatic hypertrophy.5-7 In cases of continuing dysuria, the secondary changes of hyperplasia or hypertrophy of the detrusor layer were observed.1-4 There have also been several studies investigating bladder trabeculation as a secondary change of the detrusor by a bladder outlet obstruction in men. However, only a few objective studies on female bladder outlet obstructions and its related symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis have progressed because symptoms of stress, urinary incontinence, urge incontinence, and infection, rather than those of urinary obstruction, are more prevalent in women due to differences in anatomical structures. Other reasons could include the limitations of urodynamic study for diagnosing and treating dysuria12,16-18 and patients' reluctance in visiting the hospital for urinary disturbances due to the privacy of female urination and the lack of recognition of and interest in the symptoms.

The prolapse of the urethra or bladder and the mechanical obstruction of the urinary system caused by the uterine prolapse can lead to the increase in urinary resistance and secondary changes of the detrusor. Accordingly, this study was designed to verify the correlation and significance between bladder trabeculation and a bladder outlet obstruction in patients with POP through the objective analyses of the bladder trabeculation and urodynamic studies.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Yonsei University, College of Medicine. The medical records of the patients who visited the outpatient clinic of Yonsei University Medical Center for symptoms of POP and underwent cystoscopy and urodynamic study from March 1, 1999 to March 30, 2003 were reviewed retrospectively. This study compared the patients' age, prevalence of detrusor instability, stage and site of POP, and the parameters of the urodynamic study, such as Qmax (mL/sec), Pdet (cmH2O), postvoidal residual volume (PVR, voided volume/residual volume, mL), and maximal capacity (mL), between the patients with and without bladder trabeculation on the cystoscopy. The stage and site of POP were detected and classified using the Pelvic Organ Prolapse-Quantification (POP-Q) system.19 After restoration of the prolapsed organ, the urodynamic study was performed using Dantec-5000 (Menuet, Copenhagen, Denmark), including multi-channel cystometry, urethral pressure profilometry, and uroflowmetry. The ratio of the residual urine was recorded (using the lower value of the results from the voiding cystometry and the uroflowmetry), and the presence or absence of the detrusor instability was determined by the urodynamic study. The difference in the incidence of trabeculation between the patients with and without a suspicious bladder outlet obstruction was evaluated. A suspicious bladder outlet obstruction was defined on the urodynamic study as a Qmax less than 12 mL/sec and a Pdet higher than 20 cmH2O. The statistical methods used in this study were the Student's t-test and the chi square test, with a level of significance at p < 0.05.

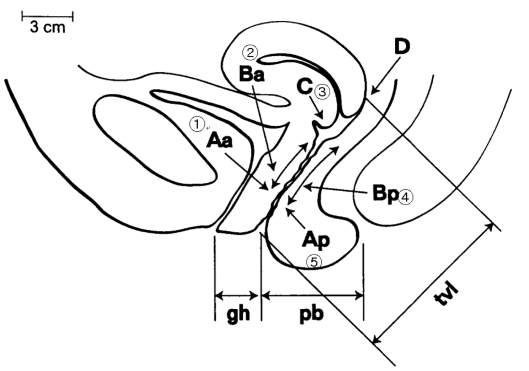

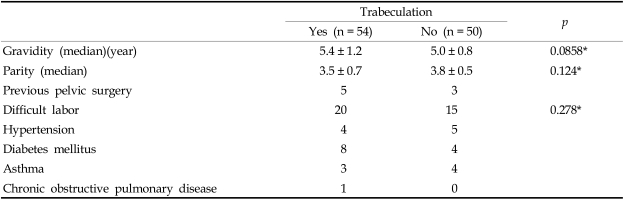

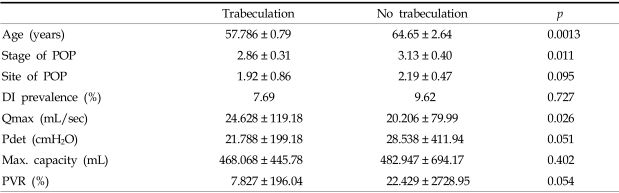

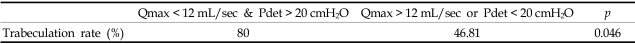

Of the 104 patients with POP, 54 had bladder trabeculation and 50 did not. Among these two groups, there was no significant difference in history of pregnancy, delivery or difficult delivery, urinary incontinence, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc. (Table 1). There was also no difference in the incidence of detrusor among the two groups. However, the mean age was significantly higher in the group with bladder trabeculation (64.65 ± 2.64 vs 57.786 ± 0.79, p < 0.05) (Table 2). The mean values of the stages in the groups with and without bladder trabeculation were 3.13 ± 0.40 and 2.86 ± 0.31 (p = 0.023), respectively, which means that the stage of POP was significantly more advanced in the group with bladder trabeculation. In addition, according to the POP sites Aa, Ba, C, Bp, and Ap, substituted with 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (Fig. 1), the mean values of the sites were 2.19 ± 0.47 and 1.92 ± 0.86 (p = 0.095) in the groups with and without the trabeculation, respectively, which means that there was no significant difference according to the POP site (Table 2). The parameters of the urodynamic study, such as Qmax, Pdet, residual urine ratio, and maximal capacity, in the groups with and without bladder trabeculation were 24.625 ± 119.18 mL/sec vs 20.206 ± 79.99 mL/sec (p < 0.05), 28.538 ± 411.94 cm H2O vs 21.788 ± 199.89 cmH2O (p = 0.052), 22.429 ± 2728.95% vs 7.827 ± 196.04% (p = 0.05), and 482.94 ± 7694.17 mL vs 468.06 ± 8445.78 mL (p = 0.402), respectively. Although Qmax was more significantly decreased in the group with trabeculation than in the group without, Pdet, residual urine ratio, and maximal capacity were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 2). Comparison of the two groups showed that the incidence of trabeculation was significantly higher in patients with a suspicious bladder outlet obstruction than without an obstruction (80% vs 46.81%, p = 0.046) (Table 3).

As the average life span of humans increases, the interest in geriatric diseases has also increased and numerous studies on POP, which commonly occurs in older women, have been undertaken. It was reported that POP accounted for approximately 0.09-0.3% of gynecological disease.15 However, this estimation is inaccurate because the symptoms of POP are quite diverse and most women do not visit the hospital owing to the prolapse. POP is a condition in which intrapelvic cavity structures, such as the uterus, bladder, urethra, or rectum, are prolapsed outside the pelvic cavity because of an incomplete pelvic supporting structure. This is caused by structural and anatomical changes in the nervous and muscular systems due to the aging process and a history of delivery or pelvic surgery. In this study, the risk factors for developing this condition were compared in the two groups and the incidences of pregnancy, delivery, urinary incontinence, and pelvic surgery, and the medical histories of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and difficult delivery were not significantly different between the groups.

Patients with POP could present with symptoms of vaginal hemorrhage, abdominal pain, lumbar pain, constipation or tenesmus, and urethral or vesical dysfunctions which can cause urinary disorders, such as frequency, nocturia, urinary incontinence, urgency, dysuria, etc. In addition, complications, such as chronic urinary tract infection or hydronephrosis, might develop, prolonging the period of urinary disorders.15 Dietz et al.20 reported that if the neck of the bladder is prolapsed over 2 cm, then the urethra is twisted. Thus, the urine flow will be significantly reduced, and when coexisting with enterocele, the maximal voiding velocity and the average urine flow will decrease.

In evaluating female patients complaining of symptoms of a lower urinary system disorder, there were not adequate examination guidelines or methods, other than a detailed history, diagnosis, and a urochemistry examination. The most commonly utilized methods were urodynamic study, endoscopy, or radiologic methods such as MRI (magnetic resonance imaging).21 Costantini et al. stated that the first method for evaluating the female patients with a urinary disorder was urodynamic study because it demonstrated over 70% of specificity, 50-100% of sensitivity, and a high negative predictive value in female patients with dysuria.22 Since subjective symptoms alone by themselves are not reliable for evaluating patients with disturbances of urination, a simple and non-invasive urodynamic study can be helpful as a basic test to diagnose those female patients19,23 and the necessity of pressure-flow study was suggested for determining the causes.24,25 However, in spite of its usefulness for diagnosing male patients with prostatic hypertrophy and a bladder outlet obstruction, there are limitations in applying this method to female patients, due to the gender-related differences in anatomic structures and causative factors of men.26 Therefore, it is necessary to study the appropriate method for examining female patients with disturbances of urination caused by POP.27

Although the incidence of a bladder outlet obstruction in women is not well known, some studies have reported an incidence of 2.7-23% incidence in women with lower urinary system symptoms.28,29 Blaivas et al.26 diagnosed bladder outlet obstructions in 50 cases (8.3%) of a total 600 cases using urodynamic study performed on the women showing lower urinary system symptoms. On the urodynamic study, the diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction was restricted by three conditions: Qmax below 12 mL/sec and over 20 cmH2O of Pdet; low Qmax and evidence of an outlet obstruction on radiologic tests with the maintenance of Pdet of at least 20 cmH2O; and the maintenance of Pdet 20 cmH2O under the transurethral insertion, but the inability to urinate. In this study, the group with a suspicious bladder outlet obstruction had below 12 mL/sec of Qmax and over 20 cmH2O of Pdet. Trabeculation was detected in 80% of this group and in 40% of the control group. Regardless of several studies reporting a correlation between bladder trabeculation and an outlet obstruction,30 the relationship is not established yet. To do so, it is necessary to construct an objective method for evaluating bladder trabeculation and a system capable of reducing the errors in evaluation methods, the examiners, and the test period. It is also essential to confirm the differences in the urodynamic study results according to the degrees of trabeculation in the patients with a suspected of a bladder outlet obstruction.

Through this study, a possible relationship between bladder trabeculation, the stage of POP and bladder outlet obstruction was suggested, but there were several drawbacks. For example, the mean age in the trabeculation group was significantly higher and this should not be overlooked because trabeculation genesis is related to aging. Therefore, confounding factors, such as age, accompanying disease, history of surgery, and stage of POP in the control group, should be studied under the same conditions. The subjects had detrusor instability on the urodynamic study and cystoscopy. Since several examiners participated in this study, interobserver variation could have existed. Additionally, the accompanying urinary disturbances should also be classified and the existence or absence of the structural or functional factors and accompanying gynecological diseases should be confirmed by tests.

Until now, an adequate method for evaluating the urinary function of patients with POP has not been suggested. Urinary dysfunction caused by POP could be improved by correcting the prolapse through surgical treatment. Results from this study indicate that a bladder outlet obstruction can be suitably diagnosed by evaluating the urinary function of POP patients through urodynamic study. Additionally, the objective evaluation of bladder trabeculation by cystoscopy could provide useful information in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with POP and concurrent urinary disturbances.

References

1. Brierly RD, Hindley RG, McLarty E, Harding DM, Thomas PJ. A prospective controlled quantitative study of ultrastructural changes in the underactive detrusor. J Urol. 2003; 169:1374–1378. PMID: 12629365.

2. Kokcu A, Yanik F, Cetinkaya M, Alper T, Kandemir B, Malatyalioglu E. Histopathological evaluation of the connective tissue of the vaginal fascia and the uterine ligaments in women with and without pelvic relxation. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2002; 266:75–78. PMID: 12049299.

3. Kojima M, Inui E, Ochiai A, Naya Y, Kamoi K, Ukimura O, et al. Reversible changes of bladder hypertrophy due to benign prostatic hyperplasia after surgical relief of obstruction. J Urol. 1997; 158:89–93. PMID: 9186330.

4. Saito M, Ohmura M, Kondo A. Effects of long-term partial outflow obstruction on bladder function in the rat. Neurourol Urodyn. 1996; 15:157–165. PMID: 8713562.

5. Witjes WP, Aarnink RG, Ezz-el-Din K, Wijkstra H, Debruyne EM, de la Rosette JJ. The correlation between prostate volume, transition zone volume, transition zone index and clinical and urodynamic investigations in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Br J Urol. 1997; 80:84–90. PMID: 9240186.

6. Reynard JM, Yang Q, Donovan JL, Peters TJ, Schafer W, de la Rosette JJ, et al. The ICS-'BPH' study: uroflowmetry, lower urinary tract symptoms and bladder outlet obstruction. Br J Urol. 1998; 82:619–623. PMID: 9839573.

7. Gomes CM, Trigo-Rocha FE, Arap MA, Arap S. Bladder outlet obstruction and urodynamic evaluation in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Braz J Urol. 2001; 27:575–588.

8. Emge LA, Durfee RB. Pelvic organ prolapse: four thousand years of treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1966; 9:997–1032. PMID: 5333791.

9. Samuelsson EC, Arne Victor FT, Tibbon G, Svardsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999; 180:299–305. PMID: 9988790.

10. Porges RF, Smilen SW. Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994; 171:1518–1526. PMID: 7802061.

11. Benassi L, Bocchialini E, Bertelli M, Kaihura CT, Ricci L, Siliprandi V. Risk of genital prolapse and urinary incontinence due to pregnancy and delivery. A prospective study. Minerva Ginecol. 2002; 54:317–324. PMID: 12114864.

12. Goh JT. Biomechanical properties of prolapsed vaginal tissue in pre- and postmenopausal women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2002; 13:76–79. PMID: 12054186.

13. Deval B, Rafii A, Poilpot S, Aflack N, Levardon M. Prolapse in the young woman: study of risk factors. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2002; 30:673–676. PMID: 12448363.

14. Sze EH, Sherard GB 3rd, Dolezal JM. Pregnancy, labor, delivery and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 100:981–986. PMID: 12423864.

15. Bai SW, Kang SH, Kim SK, Kim JY, Park KH. The effect of pelvic organ prolapse on lower urinary tract function. Yonsei Med J. 2003; 44:94–98. PMID: 12619181.

16. Lemack GE, Zimmern PE. Pressure flow analysis may aid in identifying women with outflow obstruction. J Urol. 2000; 163:1823–1828. PMID: 10799191.

17. Chassagne S, Bernier PA, Haab F, Roehrborn CG, Reisch JS, Zimmern PE. Proposed cutoff values to define bladder outlet obstruction in women. Urology. 1998; 51:408–412. PMID: 9510344.

18. Bump RC, Mattiason A, Bo K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996; 175:10–17. PMID: 8694033.

19. Blaivas JG, Groutz A. Bladder outlet obstruction nomogram for women with lower urinary tract symptomatology. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000; 19:553–564. PMID: 11002298.

20. Dietz HP, Haylen BT, Vancaillie TG. Female pelvic organ prolapse and voiding function. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2002; 13:284–288. PMID: 12355286.

21. Rovner ES, Wein AJ. Evaluation of lower urinary tract symptoms in females. Curr Opin Urol. 2003; 13:273–278. PMID: 12811290.

22. Costantini E, Mearini E, Pajoncini C, Biscotto S, Bini V, Porena M. Uroflowmetry in female voiding disturbances. Neurourol Urodyn. 2003; 22:569–573. PMID: 12951665.

23. Minardi D, Garofalo F, Yehia M, Cristalli AF, Giammarco L, Galosi AB, et al. Pressure-flow studies in men with benign prostatic hypertrophy before and after treatment with transurethral needle ablation. Urol Int. 2001; 66:89–93. PMID: 11223750.

24. Nitti VW, Tu LM, Gitlin J. Diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction in women. J Urol. 1999; 161:1535–1540. PMID: 10210391.

25. Farrar DJ, Osborne JL, Stephenson TP, Whiteside CG, Weir J, Berry J, et al. A urodynamic view of bladder outflow obstruction in the female: factors influencing the results of treatment. Br J Urol. 1976; 47:815–822. PMID: 1241332.

26. Massey JA, Abrams PH. Obstructed voiding in the femal. Br J Urol. 1988; 61:36–39. PMID: 3342298.

27. Rees DL, Whitfield HN, Islam AK, Doyle PT, Mayo ME, Wickham JE. Urodynamic findings in adult females with frequency and dysuria. Br J Urol. 1976; 47:853–860. PMID: 1241333.

28. Groutz A, Blaivas JG, Fait G, Sassone AM, Chaikin DC, Gordon D. The significance of the American Urological Association symptom index score in the evaluation of women with bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2000; 163:207–211. PMID: 10604349.

29. Pang MW, Yip SK. An overview of pelvic floor reconstructive surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. J Pediatr Obstet Gynaecol. 2003; 15:35–39.

30. EI Din KE, de Wildt MJ, Rosier PF, Wijkstra H, Debruyne FM, de la Rosette JJ. The correlation between urodynamic and cystosopic findings in elderly men with voiding complaints. J Urol. 1996; 155:1018–1022. PMID: 8583551.

Fig. 1

Schematic presentation of a female pelvic organ prolapse (POP-Q classification) and substituted number for each point. Aa, point on the anterior vagina 3 cm proximal to the external urethral meatus. Ba, most distal or dependent point of any portion of the anterior vaginal wall from point Aa to just anterior to the vaginal cuff or anterior lip of the cervix. C, most dependent edge of the cervix or vaginal cuff. Bp, corresponding point to Ba on the posterior vaginal wall. Ap, corresponding point to Aa on the posterior vaginal wall.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download