Abstract

Advanced Hodgkin's disease is usually treated with six or more cycles of combination chemotherapy. Spontaneous regression of the cancer is very rarely reported in patients with Hodgkin's disease. We present an unusual case of a patient with Hodgkin's disease who experienced complete remission with a single cycle of chemotherapy, followed by pneumonia. The case was a 36-year-old man diagnosed with stage IVB mixed cellularity Hodgkin's disease in November 2000. After treatment with one cycle of COPP-ABV (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone, doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vinblastine) chemotherapy without bleomycin, the patient developed interstitial pneumonia and was cared in the intensive care unit (ICU) for two months. Follow-up chest computerized tomography (CT), performed during the course of ICU care, revealed markedly improved mediastinal lymphomatous lesions. Furthermore, follow-up whole body CT and 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed complete disappearance of the lymphomatous lesions. Four years later, the patient is well and without relapse. This report is followed by a short review of the literature on spontaneous regression of Hodgkin's disease. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of spontaneous remission of Hodgkin's disease in Korea.

Hodgkin's disease has been diagnosed in approximately 7 per 100,000 persons annually since the disorder was first described by Thomas Hodgkin in 1832.1 Like other malignant diseases, spontaneous regression of Hodgkin's lymphoma has been reported as a very rare phenomenon. Many possible etiologies of this phenomenon have been proposed, however, the most prevalent view is that immunologic factors in the host are responsible. Spontaneous regression of Hodgkin's disease occurs very rarely compared to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. To date, only 15 cases have been reported in the literature. We report an unusual case of a patient with Hodgkin's disease who had complete remission during intensified care for interstitial pneumonia of an unidentified organism following one cycle of combination chemotherapy.

The 36-year-old male patient was admitted through the emergency room on November 30, 2000 with a 15-day history of intermittent spiking fevers and chills. He had a temperature of 38.1℃, a pulse rate of 80/min, a respiratory rate of 16/min, and a blood pressure of 130/80mmHg. There was no palpable peripheral lymph node enlargement, hepatomegaly, or splenomegaly. Initial laboratory studies revealed a hemoglobin of 11.0g/dL, a hematocrit 31.1%, a white blood cell count 4,960/µ l (neutrophils, 75.5%; lymphocytes, 12%; monocytes, 7.3%; eosinophils, 0.6%; basophils, 0.5%), and a platelet count 328,000/µl. The C-reactive protein was 11.9 mg/dL (normal < 0.8 mg/dL). He had an AST/ALT of 98/271 IU/L, total protein 6.38 g/dL, albumin 3.08 g/dL, total bilirubin 0.5 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 299 IU/L (normal 38-115 IU/L), BUN 6.0 mg/dL, and creatinine 0.8 mg/dL. The LDH was 460 IU/L (normal 225-455 IU/L) with an increased LDH5 isoenzyme fraction and β2-microglobulin 3.6 mg/dL. The tests for the IgM antibody to herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus (VZV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) early antigen were negative, and the cytomegalovirus (CMV) early antigen was not detected. Microbiologic studies including cultures of sputum, urine, stool and blood were all negative. A posteroanterior chest radiograph was normal.

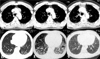

A neck computerized tomography (CT) scan showed multiple lymphadenopathy (0.5-1.2 cm in size) on the left level V, the left level II, and the right level II with well-defined, round contours without necrotic portions, strongly suggestive of benign reactive hyperplasia. A chest CT scan showed multiple areas of lymphadenopathy in the mediastinum, high and lower right paratracheal, pretracheal, aortopulmonary window, prevascular, subcarinal, paraesophageal, right and left cardiophrenic areas and the right supraclavicular fossa. The largest lymph node was measured at 3.5×2 cm in the right cardiophrenic area (Fig. 1A). The lungs were clear, without evidence of abnormal nodules (Fig. 1D). An abdominopelvic CT scan revealed hepatosplenomegaly with multiple low-density nodules on the liver and spleen as well as multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the aortocaval area, paraaortic area, and along the left iliac lymphatic chain (4 × 3 × 6 cm), and a conglomerated lymph node (3 × 2 cm) on the left renal hilum. Whole body 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) showed massive areas of hot uptake in the mediastinum, intra-abdominal lymph nodes, liver, and spleen; it showed multiple areas of hot uptake near the entire vertebra, bilateral shoulder, rib, left femur, and pelvic bones, as well as an abnormal lesion on the lungs (Fig. 2A). A whole body bone scan did not show any evidence of bone involvement. A laparoscopic biopsy of the left iliac lymph node and liver, performed on the 7th hospital day, showed mixed celluarity with high contents of epitheloid histiocytes and a few Reed-Sternberg giant cells, compatible with Hodgkin's disease (Fig. 3). Additionally, a bone marrow specimen showed no infiltration of lymphomatous cells.

The patient was diagnosed with mixed cellularity type, stage IVB Hodgkin's disease. On the 15th hospital day, he received combination chemotherapy with COPP-ABV but without bleomycin because of insufficient pulmonary function. One day after initiation of the chemotherapy, the patient complained of dyspnea on exertion and even at rest. A chest radiograph revealed slightly increased peripheral ground-glass opacities with peribronchial cuffing in both lower lung fields. He also had a positive serology for the candida antigen. Therefore, amphotericin B and acyclovir were administrated in addition to his previous antibiotics regimen, composed of cefoperazone/sulbactam and amikacin, for treatment of suspected interstitial pneumonia. Repeat microbiologic studies did not reveal any pathogens. Virologic studies including HSV IgM, VZV IgM, CMV IgM, CMV early antigen, and EBV IgM were all negative. Two days following the initiation of chemotherapy, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for low PaO2 (68mm Hg). His chest radiographs, consistent with interstitial pneumonia, continued to worsen in appearance despite the addition of trimethoprim/sulfomethoxazole and a switch of acyclovir to ganciclovir. On the 21st hospital day, a chest CT scan, performed to evaluate the abnormal chest radiographic findings, showed ground glass opacities on the periphery of both lungs with smooth bronchovascular bundle thickening and interlobular septal thickening; however, the enlarged lymph nodes in mediastinum and right supraclavicular fossa were markedly improved (Fig. 1B, 1E). The patient's dyspnea did not improve despite vigorous therapy and on the 30th hospital day the patient was started on mechanical ventilation in the ICU. One day after endotracheal intubation, trimethoprim/sulfomethoxazole was replaced with pentamidine because of the former's bone marrow suppressive effect. During the period of ICU care and mechanical ventilation, the patient experienced left foot drop, with sensory loss due to left peroneal neuropathy, nephrogenic diabetes inspidus, and pancreatitis secondary to the pentamidine. However, with maximal conservative care, on the 74th hospital day he improved enough to be transferred to the general ward and no longer required mechanical ventilation. Whole body CT scans were repeated on the 90th hospital day to assess the lymphadenopathy, noted to be improved upon follow-up chest CT scan on the 20th hospital day, because the patient had refused further chemotherapy. Interestingly, follow-up CT scans of the neck, chest and abdomen-pelvis showed no definite evidence of lymphadenopathy in the neck, intrathoracic mediastinum, markedly decreased lymphadenopathy in the paraaortic area and the left iliac chain, as well as improved hepatosplenomegaly with resolution of the previous low attenuating nodules (Fig. 1C). On 18FDG-PET images there was no evidence of lymphomatous involvement of the liver, spleen, iliac, inguinal area or spine, except for a residual lesion in the upper abdominal lymph node chain along the inferior vena cava and aorta (Fig. 2B). These findings were thought to be compatible with a partial response. Nine months following the initial chemotherapy, whole body CT (neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis) scans, 18FDG-PET, and a whole body bone scan, performed for restaging, did not show any definite evidence of lymphomatous lesions, and thus were compatible with complete remission status (Fig. 2C). On the 103rd hospital day, the patient's tracheotomy site was sealed. On the 167th hospital day, pulmonary function tests showed a vital capacity of 39.6%, FVC of 40.8%, FEV1 of 49.4%, FEV1/FVC of 122, and DLco of 58.3%. Chest radiography at this time showed diffuse and coarse reticular changes. The patient, with the support of his family, decided not to undergo further chemotherapy and he was discharged on the 198th day of hospitalization with slight dyspnea on exertion, but otherwise feeling well. Four years following hospitalization, the patient is living well, even climbing up high mountains, and is without recurrence of Hodgkin's disease.

Spontaneous regression of cancer is defined as the complete or partial disappearance of a malignant tumor in the absence of or inadequacy of therapy that is capable of inducing antineoplastic effects.2 This definition of spontaneous regression does not necessarily imply a spontaneous cure of the cancer, because it also applies to cases of incomplete or temporary regression of cancer. Although spontaneous regression of cancer is uncommon, 761 reports of individual cases and small case studies have been published between 1900 and 1987.3,4 Common clinical entities reported to have shown spontaneous regression include hypernephroma, malignant melanoma, neuroblastoma, leukemia and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.2 Spontaneous regression in malignant lymphoma has been reported primarily in patients with low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma,5,6 but rare case reports have described regression in patients with intermediate or high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and Hodgkin's disease.7-9

Untreated Hodgkin's disease has a 5-year survival rate of less than 5%.10 Spontaneous regression of Hodgkin's lymphoma is a very rare event; a search of MEDLINE identified only 15 cases of spontaneous regression of the disease, with various follow-up periods ranging from several months to eight years.11-16 Of these patients, the subtypes of Hodgkin's disease were reported in only eight cases, with the mixed cellularity being the most frequent subtype (mixed cellularity, 4 cases; lymphocyte predominant, 3 cases; nodular sclerosis, 1 case). The case described here was also of the mixed cellularity subtype. Among the 15 reported cases of spontaneous regression, five cases occurred in children following measles infection; however, all five of these patients still required treatment with chemotherapy following the regression.14,15

The etiologies underlying spontaneous remission remain unclear. The proposed mechanisms to explain this phenomenon have included the role of immunological factors, concomitant infections, hormonal factors, tumor necrosis, angiogenesis inhibition, apoptosis, elimination of carcinogens, surgical trauma on the primary tumor, or induction of differentiation.3,17

Among these possible etiologic factors, immunological mechanisms have been the most frequently used to explain spontaneous regression of Hodgkin's disease.11,16 Drobynski and Qazi reviewed the indirect experimental evidence supporting the notion that host immunological mechanisms are important in B cell lymphoma regression.17 Ono et al. suggested that highly elevated natural killing activity might be one of the possible mechanisms responsible for spontaneous regression of malignant lymphoma.18 In this study, the patients with spontaneous regression had significantly higher natural killing activities prior to cancer regression than either controls or patients without regression in the absence of episodes suggesting viral infection.

Nonspecific stimulation of the immune system may result in enhancement of host immune responses against tumors. The temporal association found between concurrent infections and spontaneous remissions of tumor suggests that infection may stimulate the immune system to induce tumor regression. Similar immunologic changes may also play a significant role in the pathophysiology of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD). In PTLD, immunosuppressive agents for prevention of graft rejection can induce disruption of T cell control of B cell growth, resulting in the proliferation of Ebstein-Barr virus infected B cells, which is followed by the development of hyperplasia or malignancy.19 This disruption of the normal immune system can be recovered by tapering immunosuppressive agents. In addition, the restored immune system can identify the abnormal lymphomatous cells and clear them out.20

It was strongly suggested that the spontaneous regression observed in our patient was most likely due to enhanced endogenous immune regulation from a concomitant unidentified infectious disease such a viral pneumonia. The immune system in our patient may have been activated during the struggle with severe interstitial pneumonia, and this intensified cellular immunity may be responsible for the spontaneous regression of the tumor. In addition, various cytokines or toxins associated with infections may also play a role in mediating regression.21,22

The experience with this case could support the possible role of infections as an important etiologic factor for spontaneous regression of Hodgkin's disease via nonspecific ostentation of host immunity. However, it is impossible to exclude the possibility that the tumor cells may have been extremely sensitive to the chemotherapeutic agents used. Therefore, the phenomenon of spontaneous regression should be studied further because a more precise understanding may make it possible to harness the host immune system to mediate tumor regression in neoplastic diseases such as Hodgkin's disease.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Serial follow up images of chest CT scans. A. Enlargement of multiple lymph nodes at the paratracheal and aortopulmonary window was noted at the time of initial diagnosis. B. The enlarged lymph nodes, noted on the initial CT scan, were found to be markedly improved on the 21st day of hospitalization. C. A CT scan performed nine months after initial diagnosis showed no abnormalities. D. No abnormalities in the lung parenchyma were found at the time of diagnosis. E. A CT scan performed at 21th day of hospitalization showed ground glass opacities in the peripheral areas of both lung parenchyma. F. Although minimal honey combing and reticular patterns remained, the ground glass opacities, noted at D, were not found with CT nine months after initial diagnosis.

Fig. 2

Serial follow up images of 18FDG-PET scans. A. The initial 18FDG-PET scan showed massive areas of hot uptake in the mediastinum, intra-abdominal lymph nodes, spleen, possibly liver, near the entire vertebrae, bilateral shoulder, rib, and left femur. B. A follow-up 18FDG-PET scan, performed 3 months after the initial chemotherapy, showed markedly decreased hot uptakes in the liver, spleen, vertebral bodies and iliac lymph nodes. C. Nine months after initial chemotherapy, there was no definite abnormal uptake noted on the 18FDG-PET scan.

Fig. 3

Pathologic features. A. Left iliac lymph node biopsy. Microscopic examination of the specimen showed mixed cellularity type Hodgkin's disease with high contents of epitheloid histiocytes and a few Reed-Sternberg cells. (H-E stain, ×400). B. Liver biopsy. Reed-Sternberg cells with background reactive cells infiltrated and replaced the liver parenchyma (H-E stain, ×40).

References

1. MacMahon B. Epidemiology of Hodgkin's disease. Cancer Res. 1966. 26:1189–1200.

2. Papac RJ. Spontaneous regression of cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 1996. 22:395–423.

3. Challis GB, Stam HJ. The spontaneous regression of cancer. A review of cases from 1900 to 1987. Acta Oncol. 1990. 5:545–549.

4. Gattiker HH, Wiltshaw E, Galton DA. Spontaneous regression in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer. 1980. 45:2627–2632.

5. Horning SJ, Rosenberg SA. The natural history of initially untreated low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1984. 311:1471–1475.

6. Krikorian JG, Portlock CS, Cooney P, Rosenberg SA. Spontaneous regression of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a report of nine cases. Cancer. 1980. 46:2093–2099.

7. Poppema S, Postma L, Brinker M, de Jong B. Spontaneous regression of a small non-cleaved cell malignant lymphoma (non-Burkitt's lymphoblastic lymphoma). Morphologic, immunohistological, and immunoglobulin gene analysis. Cancer. 1988. 62:791–794.

8. Kumamoto M, Nakamine H, Hara T, Yokoya Y, Kawai J, Ito H, et al. Spontaneous complete regression of high grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Morphologic, immunohistochemical, and gene amplification analyses. Cancer. 1994. 74:3023–3028.

9. Heibel H, Knodgen R, Bredenfeld H, Wickenhauser C, Scheer M, Zoller JE. Complete spontaneous remission of an aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with primary manifestation in the oral cavity. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004. 45:171–174.

10. Weinshel EL, Peterson BA. Hodgkin's disease. CA Cancer J Clin. 1993. 43:327–346.

11. Mangel J, Barth D, Berinstein NL, Imrie KR. Spontaneous regression of Hodgkin's disease: two case reports and a review of the literature. Hematology. 2003. 8:191–196.

12. Williams MV. Spontaneous regression of cutaneous Hodgkin's disease. Br Med J. 1980. 280:903.

13. Szur L, Harrison CV, Levene GM, Samman PD. Primary cutaneous Hodgkin's disease. Lancet. 1970. 1:1016–1020.

14. Taqi AM, Abdurrahman MB, Yakubu AM, Fleming AF. Regression of Hodgkin's disease after measles. Lancet. 1981. 1:1112.

15. Zygiert Z. Hodgkin's disease: remissions after measles. Lancet. 1971. 1:593.

16. Parekh S, Koduri PR. Spontaneous regression of HIV-associated Hodgkin's disease. Am J Hematol. 2003. 72:153–154.

17. Drobyski WR, Qazi R. Spontaneous regression in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: clinical and pathogenetic considerations. Am J Hematol. 1989. 31:138–141.

18. Ono K, Kikuchi M, Funai N, Matsuzaki M, Shimamoto Y. Natural killing activity in patients with spontaneous regression of malignant lymphoma. J Clin Immunol. 1996. 16:334–339.

19. Loren AW, Porter DL, Stadtmauer EA, Tsai DE. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder: a review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003. 31:145–155.

20. Ryu HJ, Hahn JS, Kim YS, Park K, Yang WI, Lee JD. Complete resolution of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma) with reduction of immunosuppressive therapy. Yonsei Med J. 2004. 45:527–532.

21. Nauts H. The treatment of malignant tumors by bacterial toxins, as developed by the late William B. and Coley M.D. reviewed in the light of modern research. Cancer Res. 1946. 6:205–216.

22. Balkwill FR, Naylor MS, Malik S. Tumour necrosis factor as an anticancer agent. Eur J Cancer. 1990. 26:641–644.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download