Abstract

In 1999, the Korean government made a drug pricing policy reform to improve the efficiency and transparency of the drug distribution system. Yet, its policy formation process was far from being rational. Facing harsh resistance from various interest groups, the government changed its details into something different from what was initially investigated and planned. So far, little evidence supports any improvement in Korea's drug distribution system. Instead, the new drug pricing policy has deteriorated Korea's national health insurance budget, indicating a heavier economic burden for the general public. From Korea's experience, we may draw some lessons for the future development of a better health care system. As a society becomes more pluralistic, the government should come out of authoritarianism and thoroughly prepare in advance for resistance to reform, by making greater efforts to persuade strong interest groups while informing the general public of potential benefits of the reform. Additionally, facing developing civic groups, the government should listen but not rely too much on them at the final stage of the policy formation. Many of the civic groups lack expertise to evaluate the details of policy and tend to act in a somewhat emotional way.

Korea has one of the highest levels of drug consumption in Asia, but policies related to drug use have not been developed accordingly. Most of all, the drug pricing policy has long been criticized due to its obscure operating methods and its lack of flexibility. Furthermore, until recently, both physicians and pharmacists were allowed to prescribe and dispense drugs for outpatient care. It was claimed that these underdeveloped drug-related policies allowed the overuse and misuse of drugs, and encouraged high pharmaceutical expenditures. To allegedly improve the transparency and efficiency of the drug distribution system, the Korean government launched a pharmaceutical reform. The implementation was very difficult, drawing Korea into a vortex of social and economic turmoil, culminating with five nation-wide physicians' strikes.

The Korea's pharmaceutical reform consisted of two parts. First, a drug pricing policy reform promulgated on November 15, 1999. Second, a drug policy reform declared on July 1, 2000 that mandated the separation of medical institutions and pharmacies for outpatient care (hereafter, the mandatory separation policy). Most researchers and policymakers thoroughly discussed the implementation of the mandatory separation policy,1-5 but did not focus on the drug pricing policy reform. One reason for this may be that the drug pricing policy, rather than the mandatory separation policy, is very complicated for general readers to understand. Secondly, the general public may not be thought of as a primary stakeholder regarding the drug pricing policy reform.

Without fully understanding the drug pricing policy reform, one cannot look into Korea's pharmaceutical reform or the mandatory separation policy and the resulting side effects. One reason is because it was a precursor of the mandatory separation policy. Another reason is due to the interacted, dynamic reallocation of benefits among various interest groups such as, physicians, civic groups, and multinational and domestic drug companies, and not from the headstrong pursuit of post-pharmaceutical reform benefits to physicians. Therefore, this paper will deal with the drug pricing policy reform, with particular emphasis on the role of interest groups.

In the health domain, some interest groups have been extraordinarily powerful and influential participants in the political process. They are often very effective as either defenders or opponents of health policy reforms. Deeply involved in the policy formation process, they pressure the government to change reform details for their own benefit.6-8 The case of Korea's drug pricing policy reform was no exception. Various interest groups were involved in agenda-setting and policy formation. As a result, the finalized details of the reform were far from the government's initial proposals, making it difficult to achieve the policy objective of improving the transparency and efficiency of Korea's drug distribution system.

This paper will investigate how the initial proposals of Korea's drug pricing policy reform were changed by various interest groups and what the policy reform has really accomplished. First, we review Korea's traditional drug pricing policy and its structural deficiencies. Second, we examine the drug pricing policy reform process and details, with the main focus on the role of various interest groups. The role of civic groups who appear to have few economic motives but still work for political interest will be addressed. Finally, we review the impact of the reform on Korean society and the health care sector.

Korean government has strictly regulated the prices of reimbursable drugs since the public insurance system was first introduced in 1977. The main method used to "fix" the drug price was the "officially notified price (ONP) method", whose regulation was under the supervision of a drug pricing commission for the national health insurance system. Specifically, when a new drug was first registered, its ONP was determined by adding a fixed wholesale margin and value-added tax to the ex-factory price reported by the manufacturing company. Once a drug was officially registered, its price acted as a base for the ONP of other drugs having identical constituents. The ONP of a new drug, whose weight was different from the registered ones, was determined by comparing its weight with that of previously registered and structurally similar drugs.

The ONP of a "new, innovative drug" was subject to more stringent price controls than that of domestic, generic drugs. Its price was set to the lowest value as determined from the following three methods: ① a composite price of the ONPs of similar constituents or of products having similar efficacy, ② the average ex-factory price prevailing in the advanced seven (A-7) countries plus a wholesale margin and a value-added tax, and ③ if the drug had previously been imported, the combined value of cargo, insurance, freight, and a value-added tax, multiplied by 2.1.9 As a result, the drug prices of the multinationals' innovative products in Korea were lower than in their mother countries.

The traditional drug pricing policy has long suffered harsh criticism due to its structural deficiencies. First, the reimbursed prices were too rigid, often failing to reflect true economic conditions. The government investigated actual transactions and lowered the prices if the drugs were sold at larger discounts than at the government-fixed allowable level. However, their inspections were narrowly based, restricted to several intentionally or arbitrarily chosen drugs. Second, underground pharmaceutical drug transactions were encouraged under the ONP scheme. Drug companies sought to sell products at the highest price possible, while health service providers attempted to lower prices, because the drug margin (the difference between the ONP and the actual transaction price (ATP)), was their own profit. To prevent the government from lowering reimbursed prices, drug companies often requested buyers to issue false transaction reports, stating that they had bought drugs within the government-fixed allowable level. In return, drug companies gave buyers under-the-table benefits, such as unofficial rebates, kickbacks, or even payment for trips abroad. Third, initial reimbursement prices were often incorrectly estimated, as the ONP was determined by simply adding a wholesale margin and a value-added tax to the ex-factory cost, without taking into account the effects of scale and variation in the production process. Finally, the ONP system left room for the over-prescription of drugs in order to provide higher profits to clinics, hospitals and pharmacies. Indeed, with the ONPs being far higher than the actual purchase prices, physicians and/or pharmacists were reimbursed more than they paid, guaranteeing greater profits if more drugs were distributed to patients.10

Despite its weakness, the traditional drug pricing policy endured in the Korean health system for more than 20 years. Given that details of the drug pricing policy were too complicated for the public to understand, the government acted to utilize the obscure and inefficient nature of the traditional drug pricing policy in order to compensate physicians for the losses they incurred under Korea's national health insurance system.

Specifically, when Korea extended public health insurance to the national level in 1989, the government fixed physician's fees at levels far below the supply costs to reduce the cost to the patients. According to a study of a resource-based relative value system in Korea, the weighted average fee for medical care covered by the national health insurance system was only about 65 percent of the supply costs for that care in 1997.11 For instance, the physician's fee for a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery regulated by the national health insurance system was set at about US$ 33 (equivalently, 39,670 Korean Won) in 1998.12 Although there was no contract regarding fees and benefits between the government and medical institutions, even private medical institutions, contributing about 90% of health services, had to provide medical services at the regulated fees as the Korean government forced all medical institutions to join the national health insurance system. Given the lack of public medical institutions, the government thought that the national insurance system could not be maintained without government control of private medical institutions. The physicians continued to request an increase in fees as well as a contract-based participation in the national health insurance system. The government was reluctant to accept their requests, as they ran counter to public consensus that physicians were already relatively wealthy and the public disbelief that physicians were losing money.

Instead, the government implicitly compensated for the physicians' losses by utilizing the vagueness of the traditional drug pricing policy. The government implicitly allowed physicians to make profits from the drug margins, thereby actually subsidizing physicians with drug profits rather than with physicians' fees. Because the drug pricing mechanism was complicated and technically difficult for the general public to understand, this kind of cross-subsidization worked well in soothing the physicians' concern, while blinding the general public to the truth. This seemingly stable, but actually fragile equilibrium between the government and physicians had lasted for a long time when a political change called for drastic drug policy reform in 1998.13 In the meantime, domestic drug companies remained somewhat passive between the government and physicians. The fragile political equilibrium under the traditional drug pricing policy is shown in Fig. 1.

The government of ex-President Kim Dae-Jung, who came to power in February 1998, the first so-called post-authoritarian regime in Korea, was supported by progressive members of the labor unions, the academia, and civic groups wanting reforms in various areas. However, Kim's ruling party was still in the minority in the Korean National Assembly and it was difficult to pursue the reforms demanded by his supporters. Accordingly, Kim's administration relied on civic groups to influence public consensus directly, rather than through the National Assembly. Partly being interpreted as a populist approach, Kim's dependence on civic groups suffered criticism while forcing many civic groups to carry a political agenda. Many civic groups were newly created during Kim's regime to gain his support.14,15

Kim used a similar tactic in the pharmaceutical reform. Interestingly, what the government initially targeted was not the drug pricing policy but the separation of prescription and dispensing of drugs for outpatient care. This separation had long been scheduled for launch on July 1, 1999, as specified in the Korean Pharmaceutical Law. Nevertheless, it was not an easy task because each related interest group, such as the Korea Medical Association, Korea Pharmaceutical Association and Korea Hospital Association, was ready to strike against the government if the details of the policy were not favorable to their own interests. Worse yet, the public had no idea what the policy meant, why it was needed, or how much it would cost.

Accordingly, Kim's government decided to rely on the activities of civic groups again, this time to highlight the problems of the traditional drug pricing policy in order to raise the public's interest in the reform. Notably, the civic groups with leading members in the health care reform committee of the ruling party, disclosed that physicians were enjoying huge profits resulting from the drug margins, while simultaneously incurring excessive costs of up to about 13% of medical treatment expenses, US$ 1.06 billion (equivalently, 1.28 trillion Korean Won), through the national health insurance system. It was asserted that the current drug pricing policy tempted physicians to over-prescribe drugs for their own profit.16

This disclosure attracted a great deal of attention from the media and general public. Shortly afterwards, physicians were severely criticized as having long enjoyed huge, under-the-table profits from the drug margins, excessive prescriptions and tax evasion at the expense of their patients' health and financial well-being.17 A debate arose for the elimination of the drug margins, and a substantial number of civic groups organized a united civic front and staged angry demonstrations and rallies calling for a radical pharmaceutical reform to eliminate the drug margins.18

The detailed tasks for the drug pricing policy reform included ① the selection of a method for determining the launch price of a new, innovative drug, and ② the development of a formula for determining prices of all reimbursed drugs after their launch. In the beginning, the government planned to adopt the "purchasing power parity" (PPP) method for pricing new, innovative drugs, and the "aggregate ATP" (AATP) method for pricing all reimbursable drugs after their launch.

The PPP method, recommended by the government-funded Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, is a conversion method whereby the reimbursement is based on ① the innovativeness and cost-effectiveness of a drug, ② its price in other countries, and ③ the purchasing power of Korean consumers.19 The PPP method has some illogic; for example, irrespective of the same benefit, the method must impose a higher price on a relatively higher income society. Nevertheless, the method was thought of as a new approach which could take into account the ability-to-pay, in order to determine the price of the new, innovative drugs.

Meanwhile, the AATP method was designed to increase the economic incentives for physicians to buy drugs as cheaply as possible, while decreasing the drug margins gradually. The AATP method was first proposed by the Health Care Reform Committee, an advisory group for the Korean Prime Minister,20 and details were supplemented by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs and the government-funded Health Insurance Review Agency.21 Some of the shortcomings of the AATP method were that certain drug price differentials would remain even under the new method, and that it was necessary to have most of the drug distributors report their transaction prices to the government for calculating the AATP. The government had openly stated for more than two years that it would adopt the AATP method, shaping specific details through public discussions and research done by various public institutions. The Korean government was not able to implement its plan because of the pressure exerted by domestic and multinational drug companies.

As discussed earlier in this paper, the traditional drug pricing policy worked against multinational drug companies' interests. Under the traditional drug pricing policy, there was almost no room for the multinationals to be able to raise their drug prices to the levels they wanted. The only possibility to increase their revenue was to expand their sales in the Korean health sectors. Accordingly, the multinational manufacturers of new, innovative drugs, along with their mother countries' trade agencies, have long searched for an opportunity to influence Korea's drug pricing policy. One example was to abolish the traditional pricing method and to raise the reimbursed prices of internationally innovative drugs to the same price levels operating in developed countries. Demanding that the national health insurance system increase the extensive use of their drugs, they often criticized Korea's traditional drug pricing method as a highly discriminative and effective import barrier.

Yet, such requests from multinationals went ignored for a long time until Korea started moving more aggressively toward globalization, one of the conditions of the International Monetary Fund's rescue package following the 1997's currency crisis. In the background of Korea's move to open its markets in various areas, the multinationals took an important step in developing a more effective channel of communication with the government by establishing the Korea Research-based Pharmaceutical Industry Association (KRPIA) in March 1999. Previously, their main avenue to influence the Korean government was the Korea Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, but this organization consisted mainly of domestic drug companies who were seeking to limit the multinationals' market share in the Korean market. The KRPIA employed, as a policy adviser and executive vice president, an ex-senior official of the Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Heath Insurance Review Agency. It rapidly grew to become a major lobby group, supported by foreign public and private interest groups. To mold the Korean drug pricing policy reform to fit their own interests, the KRPIA and their supporters visited the Korean government and frequently requested meetings for negotiation.22

Their efforts were not in vain. To select a method to determine the launch price of new, innovative drugs, in August 1999, the "captured" Korean government organized an eight-member task force consisting mainly of drug suppliers: five members were from multinational and domestic drug companies, while one was from each of the Health Insurance Review Agency, the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, and the government-funded Korea Consumer Protection Board.13 After approximately three months, the so-called A-7 pricing method was adopted by a majority vote (six to two),23 and replaced the long-discussed PPP method. It is worth noting that the A-7 pricing method was initially proposed by the KRPIA. According to this method, the reimbursement price for a new, innovative drug is determined by the average ex-factory price of the product in the advanced seven (A-7) countries, plus a wholesale margin and a value-added tax. This method raised the launch price of a new, innovative drug in Korea to a level higher than or equal to that of at least one of the A-7 countries. Indeed, the A-7 pricing method was implemented on July 1, 2000, with all previous discussion and support for the PPP method ignored and without any public hearing.

Meanwhile, domestic drug companies played an important role in the government choice of reimbursable drugs as opposed to the long-discussed AATP method. In an internal and covert meeting, the government surprisingly adopted the "individual ATP" (IATP) method, instead of the AATP method, as the main formula for pricing all reimbursable drugs after their launch. The IATP method was mainly supported by drug companies and their lobby groups, the Korea Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association and the KRPIA, and was duly implemented on November 15, 1999 without any further public discussion.24

According to the IATP method, the drug reimbursement price is determined by the "individual" ATPs employed between buyers and sellers, but cannot be higher than a ceiling price fixed by the government; the ceiling price itself is determined as the average of the ATPs of the drug in the previous period. Contrary to the AATP, the IATP method discourages any economic incentives for physicians to acquire drugs at cheaper prices, whereas drug companies and wholesalers seek to sell drugs at the highest possible prices, namely, the ceiling prices. Therefore, almost no possibility exists for a drug price to drop below its launch price, initially determined as its ceiling price. Because the drug price tends to stay at its launch price, drug companies strive to set the launch prices as high as possible. Despite this inherent weakness in the method, drug companies and their lobby groups were successful in convincing the government and civic groups that the IATP method could eliminate the problem of the drug margins, as physicians were reimbursed for what they had paid for the product, creating more honest and transparent pharmaceutical drug transactions. Meanwhile, domestic drug companies remained somewhat passive between the government and physicians. Fig. 2 summarizes the political dynamics which triggered the drug pricing policy reform.

Who was the major winner or loser of the new drug pricing policy? Based on the available data and anecdotal evidence, we will discuss the impact of the reform on physicians, drug companies and the national health insurance, including consumers.

The discussion of the new drug pricing policy was primarily led by the drug companies, civic groups and the government, with the physicians being largely isolated. Accordingly, physicians' interests were completely ignored in the policy. Indeed, the new drug pricing method, which officially eliminates the drug margins, removed the opportunity for physicians to have their losses subsidized. On top of this, the government planned to implement a radical type of mandatory separation reform, that is, a separation of medical institutions and pharmacies for outpatient care, as opposed to a separation of the prescription and dispensing of drugs for outpatient care. All health care institutions were legally restricted from employing pharmacists for outpatients and from locating pharmacies within their buildings or business perimeters. This implied that most health care institutions would have to incur sustainable financial losses unless physicians' medical service fees were raised.

In February 2000, just after the drug pricing policy reform and the passage of the mandatory separation reform in the Korea's National Assembly, physicians began opposition to the government on a large scale, with about 40,000 physicians demonstrating against the government. Subsequently, physicians again went on strike in the periods April 4-6, June 20-26, August 11-17, and October 6-10, 2000. During the second strike, more than 90% of clinics participated. Even the interns and residents who provide a considerable proportion of the medical services at teaching hospitals went on strike for more than four months. The entire health care system of Korea was severely disrupted for about 10 months, which drew Korea into a vortex of social and political turmoil. Pressured by complaints from the general public and the physicians' anger, the government modified the reform details to exclude injectable drugs from the mandatory separation and raised the physicians' fees five times, to a total increase of 44% of the pre-reform level.25 The fee raise may be interpreted as a process of compensation for the asserted low level of physicians' fees.

Inasmuch as drug companies were deeply involved in the drug pricing policy reform, they benefited greatly from the new policy, particularly the multinational producers of new, innovative drugs. The A-7 pricing method allowed the multinationals to raise the prices of their new, innovative drugs to the average prices of the A-7 countries, allowing drug prices to be higher than those in some A-7 countries, whose per capital GDP is more than twice that of Korea. A study by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs calculated the PPP-converted, weighted average price of new, innovative drugs. Notwithstanding its lack of methodological perfection, the study estimated the price index for new, innovative drugs in Korea as 145.6, compared to 100 in France, and being much higher than that of the UK and Japan (Table 1).26

In addition, the mandatory separation reform, which was implemented in July 2000, worked in favor of the multinationals by boosting the utilization of the new, innovative drugs that they produced. The market share of the multinationals increased sharply, doubling in only one year to 22.7% in 2000, from 9.6% in 1999. Consequently, drug imports rose an impressive 58.3%, to US $1,554 million in 2000, up from US $982 million in 1999 (Fig. 3).27-29

The new drug policy appears to have worked against the national health insurance budget in several ways.

First, the new drug pricing policy eliminated any economic incentives to report ATPs in the drug distribution process, thus sharply increasing government reimbursement prices. Indeed, the introduction of the IATP method eventually pushed the ATPs up to the ceiling prices, a situation which is reflected in the official data, which reported the average ATP of all reimbursable drugs to be as high as 99.2% of the average ceiling price.30

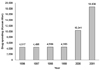

Second, the rising utilization of new, innovative drugs deteriorated the financial condition of the national health insurance budget. Patients, who are now able to compare prescriptions dispensed at various health care sources after the mandatory separation, often ask their physicians to replace generic drugs with new, high grade, innovative drugs which are used at tertiary care institutions. Physicians no longer have any incentive to prescribe cheaper drugs to patients. Accordingly, drug spending per insurance claim for outpatient care soared sharply, rising 127.3% in 2000 and 80.2% in 2001 (Fig. 4).31

Third, the increase in average physician service fee hurt the national health insurance budget. Overall, with the pharmaceutical reform firmly in place in 2001, reimbursement by the national health insurance system surged by 32.2% in just one year.32 This resulted in a huge, unprecedented deficit in the national health insurance budget, raising concerns that the system might face a serious budget crisis in the near future (Table 2).33

All of these costs could be acceptable as long as the drug pricing policy reform achieves its main policy goal of improving the transparency and efficiency of the drug distribution system. Unfortunately, there is little evidence that the new pricing policy has achieved its objectives. It was discovered that drug producers illegally kept wholesalers from offering cheaper prices to buyers, thereby maintaining the ATPs at their ceiling levels. In addition, while the drug companies supplied wholesalers with drugs at discounts ranging from 5-85% off the ceiling prices, wholesalers allegedly reported false transaction documents purporting that they still sold the drugs at ceiling prices to medical institutions and pharmacists.26 The forging of documents was, and still remains, common for drug transactions in Korea.34

The main objective of the Korean drug pricing reform in 1999 was to improve the efficiency and transparency of the drug distribution system. Motivated by long-standing criticism about its traditional drug policies, the reform itself was a move in the right direction. Yet, its policy formation process was far from being rational. Facing various interest groups involved in the reform process, the Korean government changed its details into something different from what was initially investigated and planned. For example, the selection of the IATP method instead of the AATP method eliminated the economic incentives for physicians to buy drugs at cheaper prices. This was very unusual for countries that operate national health insurance systems and naturally strive to minimize the fiscal costs of reimbursement. Moreover, adoption of the A-7 pricing method, based on the average drug prices in the advanced seven countries, ignored country-specific factors such as the potential demand, income level, or purchasing power of the country. In most countries, the pricing of new, innovative drugs goes though a case-by-case negotiation process between drug companies and private or public insurers, along with a detailed analysis of the cost-effectiveness of the drugs.35,36

So far, the reform outcome leaves much to be desired. Little evidence has supported any improvement in the efficiency and transparency of Korea's drug distribution system. The prevailing drug pricing policy reform with differences between reported and actual prices still exists. Meanwhile, the new drug pricing policy has deteriorated Korea's national health insurance budget, indicating a heavier economic burden for the general public.

From Korea's experience of the drug pricing policy reform, we may draw policy lessons for the future development of a better health care system.

As a society gets more pluralistic, the government should come out of authoritarianism and prepare thoroughly for resistance to reform in advance, by making greater efforts to persuade interest groups while informing the general public of the potential benefits of the reform. In Korea, the government did not develop any mid-term strategies for reform, and instead changed policy details whenever it faced harsh resistance from various interest groups. Additionally, the government should listen to civic groups but not rely extensively on them at the final stage of the policy formation. In Korea, amidst a lack of political support, the government mobilized civic groups to influence public opinion. However, many of the civic groups were not familiar with the details of the drug pricing policy and lacked expertise to evaluate the policy implications of the various interest groups' demands. To make matters worse, they acted somewhat emotionally. In order to eliminate the physicians' profits from the traditional drug pricing method, the civic groups blamed physicians as a selfish and rich group, yet they failed to consider the loss of the traditionally low service fees.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 4

Changes in drug spending per insurance claim for outpatient care in Korea's national health insurance, 1996-2001.31

References

1. Ahmad K. Korean doctors end crippling strike. Lancet. 2000. 356:54.

2. Lee CC, Crupi RS, Kim GW, Min YG. A challenge for reform in South Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2001. 42:152–153.

3. Watt J. Doctors' first strike in Republic of Korea likely to end. Bull World Health Organ. 2000. 78:1478.

4. Kwon S. Pharmaceutical reform and physician strike in Korea: separation of drug prescribing and dispensing. Soc Sci Med. 2003. 57:529–538.

5. Kim HJ, Chung W, Lee SG. Lessons from Korea's pharmaceutical policy reform: the separation of medical institutions and pharmacies for outpatient care. Health Policy. 2004. 68:267–275.

6. Beaufort BL. Health policymaking in the United States. 1998. 2nd ed. Chicago, Illinois: Health Administration Press.

7. Rodwin MA, Okamoto A. Physicians' conflicts of interest in Japan and the United States: Lessons for the United States. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2000. 25:343–375.

8. Morone JA, Kilbreth EH. Power to the people? Restoring citizen participation. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2003. 28:271–288.

9. Korea Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association. Policy measures for pharmaceutical industry in the 21st century. 1997. Seoul, Korea: Korea Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association;Unpublished document.

10. Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare. Report on policy measures for improving drug reimbursement pricing policy. 1999. Seoul, Korea: Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare;Unpublished document.

11. Research Institute for Health Policy and Management. Developing the resource-based relative value system in Korea. 1997. Seoul, Korea: Yonsei University.

12. Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare. Fee schedules for medical insurance. 1998. Seoul, Korea: Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare.

13. Chung W. The political economy of health policy decision-making: Korea's drug pricing policy reform. Korean Policy Studies Review. 2002. 11:99–134.

14. Cho HY. Democratic transition and changes in Korean NGOs. In : Paper presented at the 1999 Seoul International Conference of NGOs; 12 October 1999; Seoul, Korea: CONGO, NGO/DPI of UN and GCS.

15. NGOs movement without citizens. Weekly Hankook. 12 September 2002, 2000. Available at: http://www.hankooki.com/whan/200010/w200010312255446151282.htm.

16. People's Solidarity for Participatory Democracy of Korea. Survey report of drug transactions. 1998. Seoul, Korea: People's Solidarity for Participatory Democracy of Korea;Unpublished document.

17. Cho BH. Separation of prescription and dispensing, and social conflicts. In : Paper presented at the 2000 Fall Annual Meeting of The Korean Society of Health Policy and Administration; 8-9 December 2000; Seoul, Korea.

18. Ahn BC. The political character and feature in policy formation process: A case study on separation of prescribing and dispensing drugs. Korean Policy Studies Review. 2001. 10:23–55.

19. Chung W. Proposal for reimbursement pricing for innovative drugs. 1999. Seoul, Korea: Korea Institute for Health and Social Welfare;Unpublished document.

20. Health Care Reform Committee. Health care policy agenda for 21st century. 1997. Seoul, Korea: Health Care Reform Committee.

21. Chung W, Hwang I, Chae YM, Lim J. Policy recommendations for health insurance drug pricing. 1998. Seoul, Korea: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

22. Moonhwailbo. The multinational drug companies lobbying to increase prices of their products. 1999. 06. 23. Seoul, Korea: Moonhwailbosa.

23. Drug Pricing Commission of the National Health Insurance. Final report of the task force for revising drug pricing policy. 2000. Seoul, Korea: Ministry of Health and Social Affairs;Unpublished document.

24. Bureau of Health Insurance and Pension. Report of policy measures for improving drug reimbursement pricing policy. 1999. Seoul, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare;Unpublished document.

25. Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare. Overview of health insurance system in Korea. 2001. Seoul, Korea: Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare;Unpublished document.

26. Bae EY, Kim JH. Pharmaceutical price regulation in Korea. 2002. Seoul, Korea: Korea Institute for Health and Social Welfare.

27. Korea Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association. Policy recommendations for the pharmaceutical industry in the 21st century. 2001. Seoul, Korea: Korea Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association;Unpublished document.

28. Bae EY. The impact of the separation of prescription and dispensing on pharmaceutical industry. Health and Welfare Policy Forum. 2002. 64:31–39.

29. Kookminilbo. The multinational drug companies making huge amount of profits in Korea. 2002. 09. 26. Seoul, Korea: Kookminilbosa.

30. Lee GS. Problems of current drug pricing policy and its policy measures. 2001. In : Paper presented at a public hearing for revising the drug pricing policy; Seoul, Korea: Korea Hospital Association.

31. Major indicators of the national health insurance by year. Korea National Health Insurance Corporation. 2003. 20 September 2003. Available at: www.national health insurancec.or.kr/jaryo/TWEBC02_04_htm/years02.htm.

32. Korea National Health Insurance Corporation. Comparative study of the utilization pattern under the national health insurance in Korea. 2002. Seoul, Korea: Korea National Health Insurance Corporation;Unpublished document.

33. Korea Ministry of Planning and Budget. Report on the measures for stabilizing the national health insurance budget. 2002. Seoul, Korea: Korea Ministry of Planning and Budget;Unpublished document.

34. Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare. Report on a survey of drug transactions. 2002. Seoul, Korea: Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare;Unpublished document.

35. Gross DJ, Ratner J, Perez J, Glavin SL. International pharmaceutical spending control: France, Germany, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Health Care Financ Rev. 1994. 15:127–140.

36. Pickering PEM. Pricing and reimbursement in Europe: A concise guide. A Pharma Pricing Review Report. 1996. Dorking, Surrey, England: PPR Communications.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download