Abstract

A littoral cell angioma (LCA) is a rare benign vascular tumor of the spleen. A 60-year-old man, with multiple nodules in imaging study and liver cirrhosis graded as Child-Pugh classification class A, was transferred for splenomegaly. A thrombocytopenia was found on hematological evaluation. Because there was no evidence of hematological and visceral malignancy, a splenectomy was performed for a definitive diagnosis. The histological and immunohistochemical features of the splenic specimens were consistent with a LCA. After the splenectomy, the thrombocytopenia recovered to the normal platelet count. There has been no previous report of a LCA combined with liver cirrhosis. Herein, the first case of a LCA in Korea, diagnosed and treated by a splenectomy, is reported.

Primary vessel tumors are the most common type of non-lymphomatous tumor of the spleen. Most are benign, mainly arising from blood vessels (especially veins), but less commonly originate from cells in the red-pulp sinuses (Littoral cells). This type of benign tumor was first described by Falk et al. in 1991.1 The tumor arises predominantly in adults, but has been reported in children as young as 3 years old.1 Littoral cells have features lying intermediately between those of endothelial and histiocytic/macrophagic cells. There has been no previous medical report of LCA in the literature pertaining to Korea. Herein, the first case of Littoral cell angioma of spleen diagnosed and treated by splenectomy is presented.

A 60-year-old man was transferred for further evaluation of splenomegaly with multiple nodules. He has previously been diagnosed as a hepatitis B viral surface antigen (HBs Ag) carrier 10 years earlier.

The splenomegaly and liver cirrhosis were accidentally found during his first routine health care examination. The medical history of the patient was unremarkable and he had never undergone any operation.

He felt no general weakness, or suffer any fever, chill, weight loss and night sweats. The sclera was anicteric. There was no hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, tenderness and rebound tenderness on the abdominal palpation. His vital sign were as follows: blood pressure 110/70 mmHg; heart rate 70 beats per minutes and axillary temperature 36.8℃. His hematologic values were as follows: WBC 4,000/µl; hemoglobin 11.7g/dl; hematocrit 35.0% and platelet 59,000/µl, with the following biochemical values: Na+/K+ 141/4.3 mEq/L; BUN/Cr 12.6/0.90 mg/dl; total protein/albumin/globulin 5.9/3.0/2.9g/dl; AST/ALT 36/32 IU/L; total bilirubin 0.4 mg/dl; alkaline phosphatase 40 IU/L; glucose 95 mg/dl; LDH 418 IU/L; prothrombin time (PT) 16.9 sec (63%) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) 39.8 sec. The urine analysis was clear. The viral and tumor markers were as follows: HBs Ag/Ab (+/-); HBc Ig G/M (+/-); HBe Ag/Ab (+/-); HBV DNA 13.4 pg/ml, anti HCV Ab (-); anti HIV Ab (-); VDRL (-); α-FP 7.3 ng/ml; CA 19-9 12.44 U/ml and CEA 1.18 ng/ml.

The abdominal ultrasonography showed splenomegaly (13.0 cm) with a 5.7 mm sized small cyst and liver cirrhosis, with coarse, heterogeneous echogenicity and a nodular surface. The abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed splenomegaly with the multiple hypodense nodules of different sizes and liver cirrhosis featuring a nodular surface, heterogeneous density and mild atrophy of the left lobe (Fig. 1). There was no visible lymphadenopathy on the CT scan. The splenomegaly, with multiple nodules and liver cirrhosis, were found on abdominal MRI (Fig. 2).

The liver cirrhosis was graded as Child-Pugh classification class A. There was no evidence of malignancy on the imaging studies and laboratory tests. It was decided to undertake a splenectomy for the definitive diagnosis of the splenic nodules.

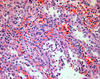

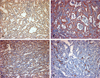

The spleen weighed 370 grams and measured 13.0 × 9.0 × 5.5 cm. On the serial sections, there were multiple circumscribed blood-filled spongy like nodules of 0.2 to 0.6 cm in size (Fig. 3). The nodules showed proliferation of the thin-walled vascular channels covered by endothelial cells that presented no atypical aspects. There were anastomosing vascular channels that attain a pseudopapillary pattern. The channels were lined by tall or flat cells, with regular indented nuclei and infrequent mitoses. The luminal spaces of the vascular channels contained exfoliated cells (Fig. 4). The immunohistochemical staining of the lining cells showed positive for Factor VIII, CD31 and CD68, and negative for CD34 (Fig. 5). The histomorphological findings were consistent with a benign splenic Littoral cell angioma.

Seven days after the splenectomy, the platelet count had become normalized (210,000/µl).

In the 1930s, endothelial cells of the vascular sinuses of the spleen were considered different from those of common endothelium, being both phagocytic and hematopoietically multipotent.2 LCA originating from the sinus endothelial cells of the splenic red-pulp was first described by Falk et al. in 1991.1

The etiology of this neoplasm remains unclear. It has been postulated that the chronic infection and systemic immunosuppression associated with aggressive visceral malignancies play a role in the pathogenesis of this type of tumor.3 However, no evidence of infection or malignancy could be found in our case.

A LCA may manifest clinically as splenomegaly, with signs and symptoms of hypersplenism (anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia),4 and because the Littoral cells have a macrophage/histiocyte-like appearance, these clinical manifestations can occur. In our case, the thrombocytopenia recovered after the splenectomy. Although liver cirrhosis itself can cause hypersplenism, it was thought that the hypersplenism in our case may have been associated with a LCA.

Pathologically, the splenic parenchyma is replaced by a vascular tumor composed of large cells, with vesicular, indented and grooved nuclei and eosinophilic to foamy cytoplasm.5 Cyst like spaces and papillary fronds can be observed in the vascular channels.6 The immunostaining profiles show positive staining for factor VIII, CD31, CD68, cathepsin D, CD 21 and BMA-120, and negative staining for CD34.7 In our case, the microscopic findings and immunostaining profiles showed the proper features of a LCA.

The ultrasonographic appearance was variable, including isoechoic8 or hypoechoic6 lesions, or mottled echotexture without discrete9 lesions. On the CT scan, they usually appear as multiple hypoattenuating masses.10 MRI showed high signal intensity on unenhanced T2-weighted images, and slightly low signal intensity on unenhanced T1-weighted images.11 MRI is the best radiological imaging method to differentiate between a LCA and other angiomatous vascular lesions.6

The diagnosis of a LCA with fine needle aspiration biopsy has rarely been reported in the literature. 12 An imaging guided percutaneous biopsy of the spleen is often avoided because the spleen is highly vascular. However, successful diagnosis of 91.0%13 and 88.9%14 of patients have been reported in recently published reviews on percutaneous biopsies. In our case, a fine needle aspiration biopsy was not performed, even though it can be tried as a diagnostic tool for evaluating splenic masses, including a LCA.

A splenectomy is the only definitive treatment. The differential diagnosis of a LCA includes lymphoma, metastatic disease, multiple hemangioma, lymphangioma, disseminated fungal infection, septic emboli and granulomatous disease (tuberculosis, sarcoidosis). Pneumocystis jirovecii, tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex, disseminated Kaposi sarcoma must be included in the differential diagnosis in immunocompromised patients.15,16 Also, a LCA has been reported in association with visceral malignancies, including colorectal, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, lung cancer (adenocarcinoma) and lymphoma.1,17 A single case of Littoral cell angiosarcoma has been reported.2 Because of the increasing risk of the subsequent development of visceral malignancies, the careful and close follow-up of patients diagnosed as LCA is recommended.18

In conclusion, herein is reported a LCA associated with liver cirrhosis. Because a LCA may be associated with visceral malignancies, it is important to differentiate a LCA from the other diseases that may accompany spleenic masses.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Enhanced abdominal CT scan shows an enlarged spleen with multiple low attenuated nodular lesions and liver cirrhosis featuring a nodular surface, heterogeneous density and mild atrophy of the left lobe.

Fig. 2

A. T2-weighted abdominal magnetic resonance image shows multiple splenic nodules with high signal intensity. B. T1-weighted abdominal magnetic resonance image shows multiple splenic nodules with iso to low-signal intensity.

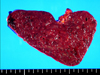

Fig. 3

The multiple circumscribed blood-filled spongy nodules of 0.2 to 0.6 cm in size located within the spleen that weighed 370 g. The capsule was intact and tensile, with a vaguely micronodular surface. The cut surface of the spleen was a dark purple color and beef-like soft.

References

1. Falk S, Stutte HJ, Frizzera G. Littoral cell angioma: A novel splenic vascular lesion demonstrating histologic differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991. 15:1023–1033.

2. Rosso R, Paulli M, Gianelli U, Boveri E, Stella G, Magrini U. Littoral cell angiosarcoma of the spleen: Case report with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995. 19:1203–1208.

3. Sauer J, Treichel U, Kohler HH, Schunk K, Junginger T. Littoral cell angioma: A rare differential diagnosis on splenic tumor. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1999. 24:624–628.

4. Goldfeld M, Cohen I, Loberant N, Magrabi A, Katz I, Papura S, et al. Littoral cell angioma of the spleen: Appearance on sonography and CT. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002. 30:510–513.

5. Ben-Izhak O, Bejar J, Ben-Elieezer S, Vlodavsky E. Splenic Littoral cell hemangioendothelioma: A new low-grade variant of malignant Littoral cell tumor. Histopathology. 2001. 369:469–475.

6. Ziske C, Meybehm M, Sauerbruch T. Littoral cell angioma as a rare cause of splenomegaly. Ann Hematol. 2001. 80:45–48.

7. Arber DA, Strickler JG, Chen YY, Weiss LM. Splenic vascular tumors: A histologic immunophenotypic and virologic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997. 21:827–835.

8. Oliver-Goldaracena JM, Blanco A, Miralles M, Martin-Gonzales M. Littoral cell angioma of the spleen. Abdom Imaging. 1998. 23:636–639.

9. Kinoshita LL, Yee J, Nash SR. Littoral cell angioma of the spleen: Imaging feature. Am J Roentgenol. 2000. 174:467.

10. Levy AD, Abbott RM, Abbondanzo SL. Littoral cell angioma of the spleen: CT features with clinicopathologic comparision. Radiology. 2004. 230:485–490.

11. Schneider G, Uder M, Altmeyer K, Bonkhoff H, Grube M, Kramann B. Littoral cell angioma of the spleen: CT and MR imaging appearance. Eur Radiol. 2000. 10:1395–1400.

12. Heese J, Bocklage T. Specimen fine-needle aspiration cytology of littoral cell angioma with histologic and immunohistochemical confirmation. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000. 22:39–44.

13. Lucey BC, Boland GW, Maher MM, Hahn PF, Gervais DA, Mueller PR. Percutaneous nonvascular splenic intervention : A 10-year review. Am J Roentgenol. 2002. 179:1591–1596.

14. Keogan MT, Freed KS, Paulson EK, Nelson RC, Dodd LG. Imaging-guided percutaneous biopsy of focal splenic lesions: Update on safety and effectiveness. Am J Roentgenol. 1999. 172:933–937.

15. Fishman EK, Magid D, Kuhlman JE. Pneumocystis carinii involvement of the liver and spleen: CT demonstration. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1990. 14:146–148.

16. Radin DR. Intraabdominal Mycobacterium tuberculosis vs Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infections in patients with AIDS: Distinction based on CT findings. Am J Roentgenol. 1991. 156:487–491.

17. Collins GL, Morgan MB, Tylor FM 3rd. Littoral cell angiomatosis with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the lung. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2003. 7:54–59.

18. Bisceglia M, Sickel J, Giangaspero F, et al. Littoral cell angioma of the spleen: An additional report of four cases with emphasis on the association with visceral organ cancer. Tumori. 1998. 84:595–599.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download