Abstract

Widespread use of antimicrobial drugs in the management of otitis media has significantly reduced the incidence of labyrinthitis nowadays. Cases of tympanogenic labyrinthitis following acute otitis media have rarely been reported in recent literature on otolaryngology. We report an unusual case of tympanogenic labyrinthitis that presented with sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) following acute otitis media in an adult who had no previous otological complaints. An audiogram revealed SNHL with pure tone threshold of 43.7 dB in the left ear. MRI was helpful to identify the inflammatory change of the membranous labyrinth. The patient's hearing returned to normal after treatment. The definite diagnosis of serous labyrinthitis was established retrospectively.

Complications of otitis media may occur when the natural defensive barriers of the middle ear are penetrated, permitting infection to spread into adjacent structures. Tympanogenic labyrinthitis is secondary to middle ear disease so it is typically unilateral. Aggressive middle ear infections may result in propagation of infection to involve round window or oval window. Nowdays, widespread use of antimicrobial agents in the management of otitis media has significantly reduced the incidence of labyrinthitis.1,2 Cases of tympanogenic labyrinthitis following acute otitis media have rarely been reported in recent literature on otolaryngology.

We report an unusual case of tympanogenic labyrinthitis in an otherwise healthy adult that presented with sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) following an episode of acute otitis media.

A healthy 29-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital in July 2002 with chief complaints of unilateral sudden hearing loss, tinnitus and dizziness. Two weeks earlier, she had developed otalgia, middle ear fullness and fever over 2 days and had been treated with antibiotics for 2 weeks under the impression of acute otitis media at a local clinic. She was referred to our deparment because of unimproved hearing loss and dizziness in the left ear, along with headache, and tinnitus, despite rigorous antibiotic treatment. She had no past history of any ear disease. Physical examination was unremarkable. She had no nystagmus, signs of meningeal irritation or neurological deficits. Otoendoscopic examination revealed a still hyperemic, tympanic membrane with purulent middle ear effusion. An audiogram revealed SNHL with pure tone threshold of 43.7 dB in the left ear (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. Contrast-enhanced, axial-T1 weighted, MRI images demonstrated minor enhancement of basal turn of cochlea, vestibule, semicircular canals and intense enhancement of mastoid in the left side (Fig. 2). These MRI findings were suggestive of otitis media with mastoiditis and membranous labyrinthitis.

The patient underwent myringotomy and insertion of ventilation tube. The purulent secretion drained from the middle ear was sent for culture. Although the culture demonstrated no growth of microorganisms, she was initially treated with intratympanic instillation of ciprofloxacin drops and put on intravenous cephalosporin (Meicelin®) injection for one week. The ECG, chest radiograph and laboratory studies were unremarkable. However, the symptoms of tinnitus and hearing loss were not resolved despite the parenteral antibiotic treatment. Under the impression of possible labyrinthitis, 5-day oral steroid treatment with prednisone (69 mg/d) was started on the 8th day after admission and was tapered off between days 10 and 12. Six days after the commencement of steroid treatment, objective improvement in hearing was first noted, and the patient was discharged. At first outpatient check-up 9 days after the commencement of steroid treatment, dramatic improvement was detected with pure tone threshold returning to 25 dB (Fig. 3). Her hearing had returned to normal at all frequencies except 8 kHz. Tinnitus continued to subside over the subsequent 1 month of outpatient follow-up (Fig. 4). Post-treatment MRI was not obtained owing to the patient's refusal off follow-up examination.

We report a case of a young woman who presented with acute suppurative otitis media and tympanogenic labyrinthitis. Nowadays, tympanogenic labyrinthitis is a rare intratemporal complication of otitis media. The decline in its incidence is partly due to earlier diagnosis, development of better antibiotics and greater awareness by medical personnel of the complications of otitis media. Acute serous labyrinthitis is a result of irritation to the labyrinth caused by otitis or meningitic infection without real bacterial invasion of the inner ear. Labyrinth irritation is induced by bacterial toxins or other mediators of inflammation.3 SNHL may fluctuate and is less severe than that often seen in suppurative labyrinthitis. Suppurative labyrinthitis caused by direct bacterial invasion into the inner ear may lead to severe, irreversible hearing loss and vertigo.

In the acute phase, serous labyrinthitis may not be easily distinguishable from suppurative labyrinthitis. However, patients with serous labyrinthitis often can retain some audiovestibular function. The signs and symptoms are less dramatic than those of purulent labyrinthitis, and the pathologic consequences in the inner ear are less destructive. Every patient with serous labyrinthitis should be observed closely for development of suppurative labyrinthitis, which presents as abrupt worsening of the vestibular symptoms and sudden loss of all hearing.4 Ludman has observed that the distinction between serous and suppurative labyrinthitis is one made in retrospect after cochlear and vestibular function has returned.5 In the present case, the diagnosis of serous labyrinthitis was established retrospectively.

Until recently, the diagnosis of tympanogenic labyrinthitis was made on clinical grounds. The presence of labyrinthitis can be speculated only if bone conduction loss co-exists with otitis media. In this case, the toxins were assumed to have penetrated the round window to affect the basal turn of the cochlea; hence the resulting hearing loss was localized at the high frequencies. MRI proves to be beneficial to confirm the presence of labyrinthine inflammation by showing enhancement of the membranous labyrinth as seen on gadolinium-contrasted, T1-weighted sequences. This enhancement is typically faint and is clearly different from the intense and localized contrast enhancement that occurs in individuals with intra-labyrinthine Schwannoma.6 The enhancing labyrinth occurs most commonly in the subacute stage. The enhancement is believed to occur due to accumulation of gadolinium within inflamed labyrinthine membranes resulting from breakdown of labyrinthine vasculature.7 Aside from the characteristic, faint, diffuse nature of the contrast enhancement, segmental involvement of the labyrinth is not uncommon. Hearing loss is also a sign a cochlear involvement, and high frequency loss is closely associated with the disease extent to the basal turn of cochlea.

Treatment for labyrinthitis caused by otitis media usually starts with establishing a drainage route and obtaining a purulence culture; appropriate antibiotic therapy is then administered subsequently. Myringotomy and ventilation tube insertion should be reserved for patients with clear evidence of serous labyrinthitis associated with otitis media. If there is persistent SNHL despite adequate antibiotic treatment, steroids should be considered as adjunctive therapy for otitis media associated with labyrinthitis. Treatment with steroid has been reported to yield a statistically significant reduction in subsequent hearing loss.8 Untreated serous labyrinthitis can ultimately lead to suppurative labyrinthitis and consequently meningitis.

In conclusion, we have described a rare case of tympanogenic labyrinthitis complicated by acute otitis media. MRI is mandatory diagnostic tool for the investigation of suspected cases.

Figures and Tables

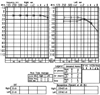

Fig. 1

Pure tone audiogram revealed a sensorineural hearing loss with pure tone threshold of 43.7 dB in the left ear on admission day.

Fig. 2

Contrast-enhanced axial-T1 weighted images of MRI demonstrated that faint enhancement of basal turn of cochlea, vestibule, semicircular canals and intense enhancement of mastoid in the left side. These MRI findings are suggestive of otitis media with mastoiditis and tympanogenic labyrinthitis.

References

1. Youngs R. Ludman H, Wright T, editors. Complications of suppurative otitis media. Disease of the Ear. 1998. 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press Inc;398–415.

2. Wetmore RF. Complications of otitis media. Pediatric Am. 2000. 29:637–647.

3. Schuknecht HF. Infections: labyrinthitis. Pathology of the ear. 1993. Pennsylvania: Lea & Febiger;211–216.

4. Dew LA, Shelton C. Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LA, Krause CJ, Richardson MA, Schuller DE, editors. Complications of temporal bone infections. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988. 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby;3047–3075.

5. Ludman H. Kerr AG, editor. Complications of suppurative otitis media. Scott-Brown's Otolaryngology. 1987. 5th ed. London: Butterworths;264–291.

6. Mafee MF. MR imaging of intralabyrinthine schwannoma, labyrinthitis and other labyrinthine pathology. Otolaryngology Clin North Am. 1995. 28:407–430.

7. Seltzer S, Mark AS. Contrast enhancement of the labyrinth on MR scans in patients with sudden hearing loss and vertigo: evidence of labyrinthine disease. AJNR. 1991. 12:13–16.

8. Rappaport JM, Bhatt SM, Burkard RF, Merchant SN, Nadol JB Jr. Prevention of hearing loss in experimental pneumococcal meningitis by administration of dexamethasone and ketorolac. J Infect Dis. 1999. 179:264–268.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download