Abstract

The herniated lumbar disc (HLD) in adolescent patients is characterized by typical discogenic pain that originates from a soft herniated disc. It is frequently related to back trauma, and sometimes it is also combined with a degenerative process and a bony spur such as posterior Schmorl's node. Chemonucleolysis is an excellent minimally invasive treatment having these criteria: leg pain rather than back pain, severe limitation on the straight leg raising test (SLRT), and soft disc protrusion on computed tomography (CT). Microsurgical discectomy is useful in the cases of extruded or sequestered HLD and lateral recess stenosis due to bony spur because the nerve root is not decompressed with chymopapain. Spinal fusion, like as PLIF, should be considered in the cases of severe disc degeneration, instability, and stenosis due to posterior central bony spur. In our study, 185 adolescent patients, whose follow-up period was more than 1 year (the range was 1 - 4 years), underwent spinal surgery due to HLD from March, 1998 to December, 2002 at our institute. Among these cases, we performed chemonucleolysis in 65 cases, microsurgical discectomy in 94 cases, and posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) with cages in 33 cases including 7 reoperation cases. The clinical success rate was 91% for chemonucleolysis, 95% for microsurgical disectomy, and 89% for PLIF with cages, and there were no nonunion cases for the PLIF patients with cages. In adolescent HLD, chemonucleolysis was the 1st choice of treatment because the soft adolescent HLD was effectively treated with chemonucleolysis, especially when the patient satisfied the chemonucleolysis indications.

The characteristic features of adolescent herniated lumbar discs (HLDs) are 1) a soft protruded disc, 2) no severe spine degeneration, 3) the typical discogenic pain is usually due to a single nerve root compression, 4) it is frequently trauma related, 5) the symptom duration is relatively short-term, and 6) it is sometimes combined with a degenerative process and a bony spur such as posterior Schmorl's node.1-6

Chemonucleolysis is the effective treatment method for adolescent HLD because the disease is characterized with typical discogenic pain due to soft disc herniation, and it is not usually combined with spinal stenosis. But if it is combined with sequestered disc particle or with posterior bony spur, the patient needs laminectomy and discectomy.3,5 In spite of the patient's young age, in the case where HLD is combined with severe disc degeneration and instability, posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) should be done. In this study we report on HLDs' clinical symptoms, the symptoms' duration, the treated segments, limitations of the straight leg raising tests, trauma relevance, the radiological findings of the herniated lumbar discs, instability, bony spurs, and congenital stenosis. In addition, we have evaluated the surgical results according to each surgical method, and we suggest the proper treatment methods for each type of adolescent HLD.

We evaluated and treated 185 adolescent patients under the age of 20, whose follow-up period was more than 1 year (1 - 4 years), and who underwent lumbar disc surgery due to HLD from March, 1998 to December, 2002. The average age of the patients was 18.4 (10 - 20) years old.

The treatment options for adolescent HLD are conservative treatment, chemonucleolysis, microsurgical discectomy, and spinal fusion with techniques like PLIF.

The principles of adolescent HLD treatment at our institute were 1) chemonucleolysis was considered the 1st line of treatment method, 2) microsurgical discectomy was a surgical method for severe extruded or sequestered disc and posterior bony spur cases, 3) PLIF was also a useful surgical method for severe disc degeneration and instability cases. We performed chemonucleolysis at our institution according to the indications set by Kim's triad of chemonucleolysis: 1. leg pain more than back pain, 2. significant SLR limitation, and 3. soft disc protrusion that was observed by CT.

We classified the adolescent HLD patients into 3 groups according to limitation of SLRT; mild limitation over 80°, moderate limitation from 45° to 80°, and severe limitation under 45°. We also classified the disc herniation as disc bulging, protrusion, extrusion, and sequestration according to the preoperative radiological findings.

The disc bulging was defined as an extension of disc beyond the disc space with a diffuse and circumferential contour, protrusion was defined as a displacement of disc material extending focally and asymmetrically beyond the disc space, extrusion was defined as a displacement of disc material extending focally and asymmetrically beyond the disc space with a greater diameter of displaced disc material than the disc material maintaining continuity with the disc of origin, and sequestration was defined as a fragment of disc that has no continuity with the disc of origin.

The patients complained of pain in both legs pain in 11 cases, left leg pain in 86 cases, right leg pain in 72 cases, and 161 patients complained both of leg pain and low back pain that occurred simultaneously. Just 16 patients among the 185 patients experienced low back pain patients without leg pain.

There were 35 patients having a symptom duration period of 1 month, 67 patients had a symptom duration period of 1 month to 3 months, 56 patients had a symptom duration period of 3 months to 1 year, and 27 patients had a symptom duration period of more than 1 year, 102 (55%) among 185 patients had a symptom duration period of 3 months or less. Especially, the short symptom duration patients were more frequently seen in the chemonucleolysis group (44/65 (67%) patients) than in the other groups.

In the chemonucleolysis group, 8, 54, and 16 segments were treated at each L3/4, L4/5, and L5/s1 level, respectively, including 13 cases of one-stage 2 level chemonucleolysis. In the microsurgical discectomy group, 7, 69, and 28 segments were treated at the L3/4, L4/5, and L5/s1 level, respectively, including 10 cases of one-stage 2 level microsurgical discectomy. In the PLIF with cages group, 2, 26, and 10 segments were treated Yonsei Med J Vol. 46, No. 1, 2005 at the L3/4, L4/5, and L5/s1 level, respectively, including 5 cases of one-stage 2 level PLIF.

The L4/5 segment was most commonly involved and treated: there was 54/65 (83%) L4/5 segment cases in the chemonucleolysis group, 69/94 (73%) L4/5 segment cases in the microsurgical discectomy group, and 26/33 (78%) L4/5 segment cases in the PLIF group (Table 1).

There are 125 patients in the severe SLRT limitation group, 45 patients in the moderate SLRT limitation group, and 15 patients in the mild SLRT limitation group. In the chemonucleolysis patients group, 53, 11, and 1 patients were included in the severe, moderate, and mild limitation groups, respectively.

36 (19.5%) patients among 185 adolescent HLD patients had HLD directly related to back traumas, 18 patients had sports related trauma, 6 patients had traffic accident related trauma, 7 patients had lifting injury trauma, and 5 patients' HLDs were due to other causes.

We classified the disc herniations as 73 bulging disc, 65 protruding discs, 22 extruding discs and 25 sequestered discs according to the preoperative radiological findings.

The adolescent HLD was combined with instability in 18 patients, with bony spur in 23 patients, and with congenital stenosis in 7 patients. Among the 18 patients with instability, we operated on 8 patients using microsurgical discectomy and on 10 patients using PLIF. There were 23 (12.4%) bony spurs, the so called posterior Schmorl's node, among 185 patients. We performed 10 microsurgical discectomy surgeries on 10 patients with bony spur on the posterolateral portion and 13 PLIF surgeries on patients with central bony spur, 14 cases of spur occurred at the L4/5 segment, and 9 cases of spur occurred at the L5/s1 segment.

There are 7 (3.8%) congenital stenosis patients among the 185 adolescent HLD patients. In the congenital stenosis groups, we performed PLIF for 3 patients and microsurgical discectomy for 4 patients.

There were 41 patients having an excellent result, 17 patients having a good result, and 7 patients having a failed result in chemonucleolysis group. The success rate (excellent and good) of chemonucleolysis was 89% (58/65).

There were 2, 3, and 2 patients, respectively, with the disc bulging type, protruded type, and extruded type among the 7 failed chemonucleolysis patients. We were willing to do microsurgical discectomy for the 4 patients who had foraminal stenosis among the 7 failed chemonucleolysis patients, but they strongly objected to open surgery and so we once again tried the chemonucleolysis.

Especially for the 22 disc extruded patients, we performed PLIF for 3 patients, microsurgical discectomy for 7 patients, and chemonucleolysis for 12 patients. There were 7 patients having an excellent result, 3 patients with a good result, and 2 patients with a failed result among the 12 chemonucleolysis treated patients. The 2 failed chemonucleolysis patients had also foraminal stenosis.

There were 74 patients with an excellent result, 18 patients with a good result, and 2 patients with a fair result in the microsurgical discectomy group. The success rate of microsurgical discectomy was 97%. The causes of the 2 fair results were low back pain due to postoperative adhesion for one patient and continuous postoperative pain owing to massive disc rupture for the second patient, the latter patient had developed foot drop preoperatively due to the preoperative neural damage.

There were 14 patients with excellent results, 17 patients with good results, and 2 patients with fair results in the PLIF group. The success rate was 93% in the PLIF with cages group. There were 2 patients who complained of postoperative low back pain.

Herniated intervertebral discs are rarely seen in children, and adolescents constitute approximately 1 - 5% of all the patients undergoing surgery for lumbar and lumbosacral intervertebral disc herniation.7,8 HLD in adolescents was 4% of all the cases of HLD we experienced (185 among a total of 4530 HLD patients), from March, 1998 to December, 2002 at our institute.

The characteristics of adolescent HLD are a soft protruded disc, no severe spine degeneration, typical discogenic pain that is usually due to a single nerve root compression, a relatively short symptom duration, it is frequently related to back trauma, and HLD is sometimes combined with a degenerative process and bony spur formation such as posterior Schmorl's node. In addition, adolescent patients frequently cannot exactly describe their pain by themselves. Parisini et al. reported that for disc herniations in the pediatric and juvenile aged patients, it is difficult to evaluate the subjective symptoms and clinical signs.6

According to Parisini et al., almost all adolescent HLD patients (82%) had low back and leg pain, only 13% of adolescent HLD patients complained of low back pain alone and 5% of adolescent HLD patients complained of leg pain alone, but lumbosacral stiffness was noted in 87% of the patients and a positive straight leg raising test was noted in 51% of the patients.6 In our study, 169 adolescent HLD patients complained of leg pain, 161 patients complained of leg pain and low back pain simultaneously, and just 16 among the 185 patients complained of only low back pain without leg pain. The causes of low back pain were mainly due to a degenerative HLD, and instability, and 3 patients' pain was related to severe cauda equina compression due to massive disc rupture.

Trauma, when considered as a severe physical stress on the lumbosacral spine (falling, heavy lifting, and extreme flexion-extension), is often mentioned as the primary causative factor.1,8 According to Clarke and Cleak, the incidence of trauma causing lumbar disc prolapse in children and adolescents was about 20%, and so the trauma was the main inciting event for the exacerbation of a pre-existing lesion.9 In our results, trauma was involved in 36 of the 185 patients (19.5%).

Lorenz and McCulloch analyzed 55 adolescents between the ages of 13 and 19 years old who underwent chemonucleolysis, and these patients had a symptom duration from two months to three years. Pain in the lower limb was the predominant symptom in 48 patients and limitation of straight leg raising was present in all patients. An anaphylactic reaction occurred in one patient and this was treated successfully. Failed chemonucleolysis occurred in 11 of the 55 patients, and these 11 patients all subsequently had surgical excision of the disc.4

Lorenz and McCulloch have reported that the long-term results of surgery were not better than the results of first-line chymopapain treatment with surgery being reserved for the failures. They suggested that chemonucleolysis should be considered as an alternative to discectomy and this was performed for their patients only after the patient failed to respond to conservative management.4

Alphen et al. have reported the excellent and good surgical results were 95% on the short term follow up, but only 87% on the long term follow up (with a mean follow-up of 12.4 years), and 10 patients underwent reintervention after 9 years on average (2 fusions and 8 reexplorations for herniated disc).10

In a comparison study between laminectomy and chemonucleolysis, Javid et al. have reported that 92% of the laminectomy patients had successful results and 82% of the chemonucleolysis patients had successful results at 6 weeks, and 88% of the chemonucleolysis patients and 85% of the laminectomy patients had successful results after 6 months. The surgical result for chemonucleolysis was better at 6 months follow up rather than at the short-term follow up.11 In another comparative analysis between 78 patients having open discectomy and 73 patients having chemonucleolysis with disc herniation, 18 patients (25%) required open discectomy following their failed chemonucleolysis; two patients (3%) in the discectomy group needed a second operation within 1 year. Comparison of the final results of the two modes of treatment 12 months after the last intervention (including second treatments) did not reveal any significant differences.10

In our study, the failed chemonucleolysis patients received reoperations; 5 patients underwent microsurgical discectomy and 2 patients underwent PLIF with cages. The time interval from chemonucleolysis to reoperation was from 3 days to 3 months (the average post-chemonucleolysis period was 26 days), 4 cases were reoperated on at 1 month and the other 3 cases were reoperated on from 1 month to 3 months.

After chemonucleolysis, the disc materials were resolved and this material changed to a liquid-gel at the time of microsurgical discectomy or PLIF with cages for the 7 failed chemonucleolysis patients.

We performed PLIF for 3 patients, microsurgical discectomy for 7 patients, and chemonucleolysis for 12 patients among the 22 disc extruded patients. The results of chemonucleolysis for the 12 disc extruded patients were excellent or good except for the 2 failed chemonucleolysis patients who had foraminal stenosis. Therefore, chemonucleolysis could be tried for the disc extruded type, if this is not combined with foraminal stenosis.

The advantages of chemonucleolysis are no back muscle trauma, a short hospital stay, no postoperative adhesion, early rehabilitation and ambulation after treatment, but there are also some disadvantages for chemonucleolysis: early disc degeneration, rare but possible anaphylactic shock, and the generally narrower indication for this procedure rather than for microsurgical discectomy.

According to Bradbury et al., chemonucleolysis is as good as primary surgery for treating adolescent's lumbar disc protrusions. In that study, the long-term outcome was good or excellent in 81% of the surgical group and 64% in the chemonucleolysis group. The patient was more likely to have satisfactory employment after chemonucleolysis than after primary surgery.7

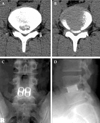

According to Alphen et al., the leakage of contrast medium out of the disc was not related to the final outcome.10 We also slowly injected the chymopapain to wet the whole disc material, in spite of contrast medium leakage on discogram, in the 2 patients who wanted only the chemonucleolysis, and we achieved an excellent and good result. We injected chymopapain very slowly to prevent chymopapain leakage in the extruded cases (Fig. 1).

According to Ishihara et al., the microsurgical discectomy procedure relieved the clinical symptoms quickly. Clinical symptoms such as low back pain and leg pain and the neurologic disturbances disappeared within 3 months after surgery for the children's lumbar disc herniation.2 Microsurgical discectomy is excellent for complete nerve root decompression, and especially for lateral recess stenosis and extruded HLD. Microsurgical discectomy has a wider surgical indication and a higher success rate than does chemonucleolysis (Fig. 2).

In some cases, microsurgical discectomy maybe produce postoperative back pain, operation related risks, and foraminal restenosis due to the postoperative disc space narrowing.

Kuroki et al. have suggested that performing the minimum discectomy necessary to decompress the nerve roots is important for maintaining the intervertebral disc functions. He also believed that the prevention of recurrent disc herniation requires complete excision of the degenerative nucleus pulposus and ruptured posterior annulus fibrosus, because even in children and adolescents, MRI or the intraoperative findings revealed a reduced water content and degenerative change of the nucleus pulposus. The proteoglycan synthesis in the intervertebral disc cells is most active in the inner annulus of the growing child. Therefore, discectomy while leaving the inner annulus intact may give rise to regeneration of the intervertebral disc.12 Narrowing of the intervertebral disc space was observed to progress up to 3 - 6 months after discectomy, but then disc space widening occurred in the children's lumbar disc herniation.2 We also completely remove the degenerated nucleus pulposus and ruptured posterior annulus fibrosus during the microsurgical discectomy, but the inner annulus was left intact to enhance the disc regeneration.

We performed the PLIF with cages in the patients with spinal stenosis for wide decompression, for segmental instability to immediately stabilize the spine, for central bony spur, and for degenerative disc disease (Fig. 3).

The mechanism of apophyseal ring fracture is a combination of two factors: congenital insufficiency of the rim plate and injury to the lumbar spine. Avulsion of lumbar vertebral rim plate is an uncommon lesion, and especially when it is seen in young adults. Its occurrence during pediatric age is very infrequent.5 But in our studies, there were bony spurs in 23 (12.4%) patients among the 185 patients. For the 23 bony spur patients, we operated on 10 patients with microsurgical discectomy for those cases of bony spur on the posterolateral portion and we operated on 13 patients with PLIF for those cases of bony spur on the central portion.

For the centrally located bony spurs, we usually removed the spur bilaterally to completely remove the spur. Bony spurs were also commonly combined with disc degeneration, and both the endplate and disc were injured during the spur removal, so PLIF with cages was an effective treatment method in cases of centrally located bony spur.

For PLIF with cages, we should, consider the growing bone in young children and the possible instrumentation related complications: for example, non-union and cage retropulsion, in addition to discectomy related risks.

We performed PLIF with cages for 3 patients with massively ruptured discs. They complained of severe low back pain due to this massive disc rupture and the narrowing of disc space that developed. We performed the PLIF with cages for disc space restoration and for the prevention of foraminal stenosis.

We achieved satisfactory results for chemonucleolysis, microsurgical discectomy, and PLIF in all groups, and the success rates were 89%, 98%, and 94%, respectively, after more than 1 year follow up. Kim et al. reported that the clinical success rate for 3000 patients treated with chemonucleolysis was 85% and for the best chemonucleolysis results, patient selection was very important. The clinical criteria for the selection of chemonucleolysis patients were a chief complaint of leg pain rather than back pain, a positive straight leg raising test, and a soft protruded disc. Other prognostic factors favoring a good outcome were young age, a short duration of symptoms, and no bony spur or calcification on radiological study.3

Adolescent HLD was mainly characterized by severe leg pain, severe limitation of straight leg raising test, a soft protruded disc, young age, and short symptom duration, so chemonucleolysis was a safe, effective, and minimally invasive treatment method for teenager soft disc herniation.

In adolescent HLD, the chemonucleolysis is the 1st choice of treatment because the soft adolescent HLD is responsive to chemonucleolysis, and the patients especially satisfy the chemonucleolysis indications. However, microsurgical discectomy is useful in cases of severe extruded disc, sequestered disc, and HLD combined with bony spur.

It there is severe disc degeneration, central bony spur, and lumbar instability for the adolescent HLD, then in spite of the young age, PLIF is the effective surgical treatment method in these cases.

Proper selection of the surgical method according to the disc condition for adolescent HLD patients is the key to achieving the best results.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1A) Computed tomogram revealed left side soft disc protrusion. B), C) On discogram, the contrast dye leaked slightly. So we injected the chymopapain very slowly for 10 minutes. After chemonucleolysis, the pain subsided completely. |

| Fig. 2A) A sequestrated disc particle migrated downward on the left side L3/4 segment. B) The extruded disc particle was shown on the left side L5/s1 segment. We performed microsurgical discectomy to remove the ruptured particle in 2 cases. |

References

1. Epstein JA, Epstein NE, Marc J, Rosenthal AD, Lavine LS. Lumbar intervertebral disk herniation in teenage children: recognition and management of associated anomalies. Spine. 1984. 9:427–432.

2. Ishihara H, Matsui H, Hirano N, Tsuji H. Lumbar intervertebral disc herniation in children less than 16 years of age. Long-term follow-up study of surgically managed cases. Spine. 1997. 22:2044–2049.

3. Kim YS, Chin DK, Yoon DH, Jin BH, Cho YE. Predictors of successful outcome for lumbar chemonucleolysis: analysis of 3000 cases during the past 14 years. Neurosurgery. 2002. 51:123–128.

4. Lorenz M, McCulloch J. Chemonucleolysis for herniated nucleus pulposus in adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985. 67:1402–1404.

5. Martinez-Lage JF, Poza M, Arcas P. Avulsed lumbar vertebral rim plate in an adolescent: trauma or malformation? Child's Nerv Syst. 1998. 14:131–134.

6. Parisini P, Di Silvestre M, Greggi T, Miglietta A, Paderni S. Lumbar disc excision in children and adolescents. Spine. 2001. 26:1997–2000.

7. Bradbury N, Wilson LF, Mulholland RC. Adolescent disc protrusions. A long-term follow-up of surgery compared to chymopapain. Spine. 1996. 21:372–377.

8. Lee JY, Ernestus RI, Schroder R, Klug N. Histological study of lumbar intervertebral disc herniation in adolescents. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000. 142:1107–1110.

9. Clarke NM, Cleak DK. Intervertebral lumbar disc prolapse in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 1983. 3:202–206.

10. Van Alphen HA, Braakman R, Bezemer PD, Broere G, Berfelo MW. Chemonucleolysis versus discectomy: a randomized multicenter trial. J Neurosurg. 1989. 70:869–875.

11. Javid MJ. Chemonucleolysis versus laminectomy. A cohort comparison of effectiveness and charges. Spine. 1995. 20:2016–2022.

12. Bayliss MT, Jonestone B, O'Brien JP. Proteoglycan synthesis in the human intervertebral disc, Variation with age, region and pathology. Spine. 1988. 13:972–981.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download