Abstract

Objective

We wanted to compare the efficacies of 95% ethanol and 20% hypertonic saline (HS) sclerotherapies that were performed in a single session under CT guidance for the management of simple renal cysts.

Materials and Methods

A prospective series of 74 consecutive patients (average age: 57.6 ± 8.1 years) with simple renal cysts were enrolled in this study. They were randomized into two groups and 95% ethanol or 20% HS, respectively, corresponding to 25% of the aspiration volume, was injected. Treatment success was determined six months later with follow-up clinical evaluation and performing ultrasonography.

Results

The sclerotherapy was accepted as technically successful without major complications in all except two patients who were excluded because of a communication between the simple renal cyst and the pelvicalyceal collecting system. Thirty-six patients in the ethanol group received sclerotherapy with 95% ethanol and 36 patients in the HS group underwent sclerotherapy with 20% HS. The complete regression ratio of the ethanol group was significantly higher (94% versus 72%, respectively) than that of the HS group. There was one patient with partial regression in each group. The failure ratio of the ethanol group was significantly lower (3% versus 25%, respectively) than that of the HS group.

Conclusion

Ethanol sclerotherapy under CT guidance is a successful and safe procedure and it can be used for the treatment of simple renal cysts. Sclerotherapy with 95% ethanol is more effective than 20% HS sclerotherapy. Sclerotherapy with HS may be an option for patients preferring to undergo a less painful treatment procedure.

Simple renal cysts are the most common renal masses, and they account for approximately 65 to 70% of all of them (1). They often occur in patients over the age of 50 as has been determined with performing postmortem examination or renal ultrasonography (US) (2, 3). Simple renal cysts are often incidentally discovered on US, CT or urography examinations that are performed for urinary tract problems or other abdominal problems. The characteristic appearance of simple renal cysts on US, CT and magnetic resonance imaging allows the radiologist to make an accurate diagnosis. US is commonly used to exclude the possibility of benign or malignant pathology because the kidney is readily accessible for US examination (4).

A small proportion of simple renal cysts may be associated with symptoms, of which pain is the commonest. Hematuria, hypertension, pelvicalyceal obstruction and cyst rupture are less common symptoms (2). When cysts are very large, they may produce the mechanical effects of a space-occupying lesion. Percutaneous or surgical intervention is considered necessary only when the cyst produces symptoms such as significant pain, an abdominal mass, hematuria, calyceal obstruction and/or hypertension secondary to renal segmental ischemia (5-8). Symptomatic renal cysts can be treated by percutaneous aspiration, with or without the injection of sclerosants, and by open or laparoscopic surgery (9-11). For the symptomatic cases, treatment of the cyst is usually accompanied by remission of the symptoms (12). The decortication of peripheral and peripelvic cysts via laparoscopy is a safe, minimally invasive and effective treatment for symptomatic renal cysts, and this method has a more durable response than that of open surgery (13), yet laproscopy is costly and it must be performed under general anesthesia. On the other hand, percutaneous aspiration and sclerotherapy are minimally invasive options. The data that's currently available suggests that ethanol sclerotherapy for treating simple renal cysts has not yet been performed with a standardized method (12). There is no consensus in the scientific literature about the best way to treat simple renal cysts with sclerotherapy (8, 12, 14-16). There have been several studies that have focused on patients with cystic hydatid disease of the liver and who were treated with the percutaneous aspiration and injection of hypertonic saline (17-19). There have been no studies that have evaluated the use of hypertonic saline for the management of simple renal cysts.

The aim of this study was to compare the efficacies of 95% ethanol and 20% hypertonic saline sclerotherapies that were performed during a single-session for the management of symptomatic simple renal cysts.

Written informed consent was obtained from each subject, and our Human Ethics Committee approved the study protocol. A prospective series of 74 consecutive patients (44 males and 30 females) who presented with symptomatic simple renal cyst were enrolled in this study to undergo sclerotherapy. These patients were seen between July 2002 and July 2005 at our hospital, and their average age was 57.6±8.1 years (age range: 40-72 years). The causes of referral to our department were flank pain in 67 patients, hydronephrosis and flank pain in two patients and examining the patient to reassure them due to the increasing cyst size in five patients. All the patients presented with flank pain and these symptoms were present for five to 13 months (mean 7 months) prior to admssion. For patients to be eligible for the study, their flank pain had to be non-colicky, ipsilateral to the cyst and not related to posture. Other causes of flank pain were excluded by the urologic evaluation that was done before referral to our department. The exclusion criteria were previous treatments for the renal cyst except for oral paracetamol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics, a communication between a simple renal cyst and the pelvicalyceal collecting system, abnormal renal function, polycystic or cystic dysplastic kidneys, those disorders that could possibly account for the presence of cysts (tuberous sclerosis or a previous malignancy), and peripelvic simple renal cysts.

A simple renal cyst was diagnosed when it satisfied the criteria of Bosniak (20, 21). The diagnosis was obtained by abdominal US, and this was followed by a CT scan only when the visualization was inadequate on the US scanning performed by our study's radiologists. CT scan was used for five patients because of the inadequate US imaging. The US criteria for the diagnosis of a simple renal cyst included 1) a spherical or ovoid shape, 2) the absence of internal echoes, 3) the presence of a thin, smooth wall that was separate from the surrounding parenchyma and 4) enhancement of the posterior wall that indicated there was transmission of US through the water-filled cyst with no calcification, no septa and no Doppler signals from within the cyst (22). The diagnosis of a simple renal cyst was made on the basis of the typical radiological findings with surrounding normal renal parenchyma, normal renal function and no associated systemic illnesses or disorders. The volume of the cyst was estimated by US with multiplying 3 diameters by the constant 0.5236 and also with considering that the cyst's shape resembled a sphere. We used the following CT criteria for a renal mass that was called a Bosniak class I cyst: a uniform cyst density of no greater than 20 HU (the assigned density of water was 0 HU, and the cysts' density ranged from -20 to +20 HU [23]), no enhancement of the mass on the CT images obtained after the administration of contrast medium (i.e., no increase in the Hounsfield units), and a round or oval shape with no perceptible wall (24).

The sclerotherapy was performed under CT guidance on an outpatient basis. The patients were placed in the prone position and local anesthesia was achieved with 2% lidocaine hydrochloride that was applied to the puncture site. The patient was given nothing by mouth for 4-8 hours prior to the procedure. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered 60 minutes prior to the procedure and they were continued for at least 24 hours after the procedure. For all the patients, their coagulopathies were corrected prior to the procedure to decrease the chance of developing a perirenal hematoma or renal hemorrhage. Patients with bleeding tendencies, including those who were taking anticoagulants, did not undergo sclerotherapy until their clotting parameters were brought within normal limits, when possible. A pigtail catheter 5.4-Fr (PBN Medicals, Denmark) was inserted with using a trocar-catheter system under CT guidance (Figs. 1A, B). The cyst fluid was aspirated as completely as possible and it was sent to the laboratory for cytologic and biochemical examination. The total amount of the aspirated fluid was measured to record the cyst's volume. The cyst was then filled with a half-and-half mixture of water-soluble contrast medium (Telebrix 35 [350 mg iodine/ml], Guerbet Laboratories, Aulnaysous-Bois, France) with normal saline. For patients who were undergoing sclerotherapy, contrast medium was instilled into the cyst to ensure that there was no communication with the pelvicalyceal collecting system, to exclude any leakage from the puncture site into the retroperitoneal cavity and to determine the presence of extravasation (Fig. 1C). The patients were then randomized into the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups; 95% ethanol or 20% hypertonic saline, respectively, which corresponded to 75% of the aspiration volume, was injected through the catheter into the cyst and this was left in place for 20 minutes. However, for a large cyst greater than 400 ml, the amount of sclerosants was limited to 100 ml to avoid systemic side effects. Before removal of the ethanol or hypertonic saline, the patients were placed in the prone, supine, and lateral decubitus positions for a minimum of 5 minutes each to allow adequate contact of the ethanol with all areas of the cyst wall (25). The ethanol or hypertonic saline was then removed and the pigtail catheter was removed (Fig. 1D). Sclerotherapy was deemed as technically successful if the procedure went uneventfully without any complication.

Evaluations that included asking questions about residual pain, a physical examination and routine abdominal US performed by the same radiologist who performed the puncture, were done at one, three and six months after treatment, with special attention being given to the segment of the kidney in which the treated cyst had been located. CT imaging after sclerotherapy was required for three patients because of inadequate US visualization of the kidneys.

Six months after sclerotherapy with performing follow-up clinical and US evaluations, the treatment success was evaluated according to regression of the cyst and the improvement of the previous clinical symptoms and findings. Disappearance of the renal cyst with the absence of the previous clinical symptoms and findings was considered as complete regression. A reduction in the volume of the cyst of more than half the volume before sclerotherapy was performed when there was partial improvement of the previous clinical symptoms and the findings were considered as partial regression. Treatment was accepted to have failed when the cyst recurred to more than half the previous volume before sclerotherapy and/or when no there was improvement of the previous clinical symptoms and findings. After failure of sclerotherapy, the patients underwent sclerotherapy again with the same sclerosant for up to three times if they had persistent flank pain.

The volume of the cysts and the presence of complete or partial regression and failure at the follow-up were all recorded. The presence of pain during filling the cyst with sclerosant and also the presence of pain after the procedure were also recorded. The cystic volumes of the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test. The complete regression and failure ratios of the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups were analyzed with the χ2 test.

The sclerotherapy was technically successful in all but two patients, and these patients were excluded because a communication existed between their simple renal cyst and the pelvicalyceal collecting system. Of the remaining 72 patients, 36 patients in the ethanol group received sclerotherapy with 95% ethanol, and 36 patients in the hypertonic saline group underwent sclerotherapy with 20% hypertonic saline. There were no major complications in the study groups and no signs of intoxication with the use of sclerosants. There were no significant differences between the types and volumes of the administered and removed sclerosants in the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups (p = 0.311 and p = 0.471, respectively). The cytology examination of the fluid was negative for neoplastic cells in all the patients, and biochemical analysis of the cystic fluid showed findings similar to those of the corresponding plasma.

Figure 2 presents the volume of the simple renal cysts in the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups. There was no significant difference between the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups for the median volume of the simple renal cysts (165 [52-480] vs. 178 [42-520] cm3, respectively, p = 0.995).

Figure 3 displays the number of patients in the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups with complete and partial regression, and those with failure at the follow-up six months after sclerotherapy. The number of patients of the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups with complete regression were 34 and 26, respectively. The complete regression ratio of the ethanol group was significantly higher (94% vs. 72%, respectively) than that of the hypertonic saline group (p = 0.024). There was one patient each with partial regression in both the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups. The partial regression ratios of the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups were similar (3% vs. 3%, respectively). The number of failures of the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups was one and nine, respectively. The failure ratio of the ethanol group was significantly lower (3% vs. 25%, respectively) than that of the hypertonic saline group (p = 0.014).

After failure of the sclerotherapy, the procedure was repeated with the same sclerosant because of persistent flank pain. The procedure was repeated one more time in one patient in the ethanol group and one more time in five patient, two more times in two patient and three more times in two patient in the hypertonic saline group. At the end of the study, the flank pain was controlled in all the patients with repeated sclerotherapies. Complete regression was obtained for the repeatedly treated patient in the ethanol group and for the seven repeatedly treated patients in the hypertonic saline group. Partial regression was obtained in two of the nine patients who required repeated sclerotherapy in the hypertonic saline group.

There were no other serious complications after therapy in the study groups. During the sclerotheraphy, ten patients in the ethanol group developed mild flank pain that required medical management with an oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug during the filling of the cystic cavity with the sclerosant. There was no pain during the filling of sclerosant in the hypertonic saline group.

Simple renal cysts are by definition unilocular, they do not communicate with the collecting system, they occur in a kidney that is otherwise normal and they have an epithelial lining that contains no renal elements. The vast majority of simple cysts encountered in clinical practice develop in otherwise normal kidneys and these cysts are now considered to be acquired lesion, and the age-dependence of cysts has been detected in several studies as evidence in favor of this concept (26). These occur as multiple or single, usually cortical, cystic spaces that vary widely in diameter. They are commonly 1 to 5 cm, but they may reach 10 cm or more in size.

Although the vast majority of simple renal cysts are entirely asymptomatic and do not require any treatment, intervention is needed when they are symptomatic and cause obstruction of the urinary tract. Simple renal cyst that develop adjacent to the renal hilum can cause flank pain, abdominal pain, hematuria, recurrent urinary infections, hypertension, polycythemia and/or obstructive uropathy (6, 27). Spontaneous, iatrogenic or traumatic rupture of a large renal cyst will also cause hematuria or pain. The first line of therapy for pain secondary to benign renal cysts is medical management with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents or narcotics. When this therapy is insufficient or other symptoms occur, then decompression may be indicated. The treatment options include percutaneous aspiration with or without sclerosis, percutaneous resection and fulguration or marsupialization, ureteroscopic cyst marsupialization, laparoscopic or retroperitoneoscopic resection, or open surgical resection (28). Should medical management fail for symptomatic peripheral renal cysts, then aspiration and sclerotherapy are preferred as the initial therapy unless these procedures are contraindicated by the cyst size or complexity due to the risk of obstructing the collecting system (29).

With modern imaging methods, most renal cysts are aspirated as part of the therapeutic process in symptomatic patients. To improve the efficacy, several sclerosant agents are currently used to injure the cyst wall cells, which are responsible for the fluid dynamics of the cyst (6). The inflammation induced by the sclerosant leads to adhesion of the walls and reduction or resolution of the renal cyst. Ethanol is the most widely used among the available sclerosant agents (7, 8, 13). Ethanol might destroy the epithelial wall of the cyst without damaging the adjacent renal parenchyma because its penetration through the fibrous capsule only occurs after 4-12 hr (30). There are published studies related to the successful use of hypertonic saline sclerotherapy in patients with hydatid liver cysts as a primary treatment (31, 32). Kabaalioglu et al. (33) reported a case of 6-year-old girl with a symptomatic renal cyst, and she underwent successful percutaneous aspiration and sclerotherapy with hypertonic saline under US guidance. They suggested that US- or CT-guided percutaneous sclerotherapy should always be considered before surgery.

Ethanol sclerotherapy has been reported to be successful via performing multi-session treatment with placement of a pigtail catheter inside the cyst for repeated instillation and removal of the alcohol (10). Chung et al. (8) reported that multiple sessions of sclerotherapy are better than a single injection of sclerosant for reducing the recurrence of simple renal cysts. Falci-Junior et al. (12) suggested that the complete disappearance of the cyst might take as long as six months; therefore, an abdominal US examination that revealed the residual cyst during this period did not signify failure or recurrence. They also reported that six months after single-session sclerotherapy, the procedure might be safely repeated to treat any symptomatic cyst that has recurred. Akinci et al. (14) assessed the efficacy and long-term results of single-session ethanol sclerotherapy for treating simple renal cysts. They performed the sclerotherapy procedures with the guidance via fluoroscopy and US for 98 simple renal cysts. In that study, the average reduction of the cyst volume was 93% at the end of the first year and the cysts disappeared completely in 17 (17.5%) patients. After the procedure, improvement of the flank pain was noted in 67 (90%) patients. Sixty-one (82%) patients were free of pain and the pain decreased in six (8%) of them. Second intervention was required in two patients (2%) due to recurrence of cysts and the related symptoms. One (1%) patient had a small retroperitoneal hematoma that resolved spontaneously and in another patient (1%), spontaneous hemorrhage was detected in the cyst one year after the procedure.

In this study, single-session percutaneous sclerotherapy was preferred since it was a good option for treating symptomatic renal cysts and it was a highly effective procedure that offered the benefits of a less-invasive approach. Multi-session sclerotherapy is a more time consuming procedure than single-session sclerotherapy; therefore, its morbidity rate may be high because of repeated procedures (13). CT and US are alternative image-guidance systems that are used during percutaneous sclerotherapy for simple renal cyst. We preferred CT-guidance during sclerotherapy because of its advantages for determining the presence of a communication between the simple renal cyst and the pelvicalyceal collecting system after filling the cyst with contrast medium, for exclusion of any leakage from the puncture site into the retroperitoneal cavity and for determining the presence of extravasation.

Okeke et al. (6) reported that laparoscopic de-roofing of the cyst is a more effective treatment than single-session sclerotherapy when a symptomatic cyst is established and when definitive treatment of a cyst is indicated. On the long term follow up (mean: 17 months, range: 12-23 months), pain recurred in all five patients who presented with pain and who also underwent sclerotherapy. The high recurrence rate for sclerotherapy might be due to the lower ethanol volume, which was a maximum of 75 ml and 20% of the cyst volume. Lin et al. (34) compared the therapeutic results of the 2- and 4-hr retention techniques during ethanol sclerotherapy with a single-session single-injection technique for treating simple renal cysts. In that study after complete aspiration of the cystic fluid, 95% ethanol was injected into the cyst and it was retained for 4 hr in 14 cysts and for 2 hr in 22 cysts. They found that the average maximal diameter and aspirated volume of the cysts were 8.3 cm and 223 ml in the 2-hr retention group and 7.9 cm and 167 ml in the 4-hr retention group, respectively. They regularly followed up the patients by performing US, CT or both at 3-month to 6-month intervals for at least one year. They concluded that the single-session, prolonged ethanol-retention technique is safe and efficacious for the treatment of renal cysts and there was no difference in therapeutic efficacy between the 2- and 4-hr ethanol-retention techniques.

Gasparini et al. (16) evaluated the efficacy of pure ethanol for the treatment of symptomatic renal cysts. They treated 14 patients who had renal cysts with a mean diameter of 10 cm (range: 5-15 cm). They used the following technique: US-guided percutaneous puncture with an 18-gauge needle, positioning of a 5-Fr catheter, complete cyst fluid aspiration, injection of a volume of pure alcohol equal to 15% of the initial cyst volume and alcohol aspiration after 90 min. They repeated the procedure eight times within five days. Their patients were followed up by US and/or CT scan for one year. After the study, all of their patients had become symptom free. Follow-up showed a progressive reduction of the cyst diameter in all cases. Only three cysts (in 2 patients and the cystic diameters were < 2 cm) persisted after 12 months. No significant complications were observed. They concluded that injections of pure ethanol into renal cysts and repeated for five days were effective for eliminating recurrences and the related symptoms. They did not record any significant complications. They suggested that pure ethanol sclerotherapy could be the first-choice procedure for the treatment of renal cysts instead of surgical managements, and this was because of the good results and the low cost of ethanol.

Percutaneous sclerotherapy is rarely associated with significant complications. We had no major complications after sclerotherapy, which is similar to the reports of other authors who found no major complications or alcohol intoxication (10, 13, 15, 16, 34). However, intense pain during filling of cysts with alcohol was reported by De Dominicis et al. (35) in a few patients who were unable to tolerate the procedure. Okeke et al. (6) found instant severe pain with a radicular distribution after ethanol injection for a painless cyst that presented as a renal mass. In our study, ten patients had transient mild flank pain that required medical management with an oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug during filling the cyst with 95% ethanol. The patients experienced n no pain during filling with 20% hypertonic saline.

The optimum agent for renal cyst sclerotherapy remains to be determined. Alcohol at a 95% concentration is the most commonly used sclerosing material for cyst ablation (15, 34), and 99.8% alchohol is commonly used too (16). Several factors for achieving sucessful renal cyst sclerotherapy with alcohol require optimization, such as the concentration of alcohol (95% or 99%), its volume in relation to the cystic volume, the duration of sclerotherapy per session, the number of injections required in relation to the cystic volume and whether continuous drainage is needed before and after sclerotherapy. In our study, the alcohol was retained in the cyst for 20 minutes to expedite the destroying action on the cyst epithelium without the alcohol penetrating the renal parenchyma or entering the circulation. A small-caliber pigtail catheter was used in our patients, with no tract dilatation, and there was no damage to the collecting system or adjacent organs. Single-session percutaneous 95% ethanol or 20% hypertonic saline sclerotherapy with CT guidance can be used for the management of simple renal cysts, and the technical success rate is close to 100%. There were no major complications in our study population and no signs of intoxication with the use of sclerosant agents. In the same clinical settings, 20% hypertonic saline sclerotherapy was not as successful as 95% ethanol sclerotherapy, but it may be an alternative option for patients who prefer a less painful procedure.

Our results suggest that CT-guided sclerotherapy with 95% ethanol in a single-session, and according to the protocol described in this study, is preferable as a first therapeutic option. Although the efficacy of 20% hypertonic saline sclerotherapy in our study was lower than that of the 95% ethanol sclerotherapy, 20% hypertonic saline may have a place in the armory of interventional radiologists for the managing symptomatic simple renal cysts. Further study and follow-up is needed to assess the long-term effects of 20% hypertonic saline sclerotherapy on the outcome of symptomatic simple renal cyst to determine the duration of pain for these procedures and the rates of cyst recurrence.

Figures and Tables

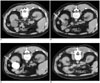

Fig. 1

Representative CT images of a 53-year-old male patient with a simple renal cyst.

A. The simple renal cyst before aspiration.

B. A 5.4-Fr pigtail catheter was inserted into the cyst.

C. Contrast medium is instilled into the cyst to ensure that there was no communication with the pelvicalyceal collecting system, to exclude any leakage from the puncture site into the retroperitoneal cavity and to determine the presence of extravasation.

D. The cyst disappeared after successful ethanol sclerotherapy.

Fig. 2

Scatter dot plot with median line graphics of the volume of the simple renal cysts in the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups. There was no significant difference of the cyst volume between the study groups (p = 0.995).

Fig. 3

The number of patients, with complete and partial regression and failure at six months follow-up after sclerotherapy, in the ethanol and hypertonic saline groups. Their percentages are also presented.

aP = 0.024 vs. the complete regression ratio of the hypertonic saline group with using Fisher's exact test.

bP = 0.014 vs. the failure ratio of the hypertonic saline group with using Fisher's exact test.

References

1. Clayman RV, Surya V, Miller RP, Reinke DB, Fraley EE. Pursuit of the renal mass. Is ultrasound enough? Am J Med. 1984. 77:218–223.

2. Caglioti A, Esposito C, Fuiano G, Buzio C, Postorino M, Rampino T, et al. Prevalence of symptoms in patients with simple renal cysts. BMJ. 1993. 306:430–431.

3. Ravine D, Gibson RN, Donlan J, Sheffield LJ. An ultrasound renal cyst prevalence survey: specificity data for inherited renal cystic diseases. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993. 22:803–807.

4. Marumo K, Horiguchi Y, Nakagawa K, Oya M, Ohigashi T, Asakura H, et al. Incidence and growth pattern of simple cysts of the kidney in patients with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. Int J Urol. 2003. 10:63–67.

5. Rockson SG, Stone RA, Gunnells JC Jr. Solitary renal cyst with segmental ischemia and hypertension. J Urol. 1974. 112:550–552.

6. Okeke AA, Mitchelmore AE, Keeley FX, Timoney AG. A comparison of aspiration and sclerotherapy with laparoscopic de-roofing in the management of symptomatic simple renal cysts. BJU Int. 2003. 92:610–613.

7. el-Diasty TA, Shokeir AA, Tawfeek HA, Mahmoud NA, Nabeeh A, Ghoneim MA. Ethanol sclerotherapy for symptomatic simple renal cysts. J Endourol. 1995. 9:273–276.

8. Chung BH, Kim JH, Hong CH, Yang SC, Lee MS. Comparison of single and multiple sessions of percutaneous sclerotherapy for simple renal cyst. BJU Int. 2000. 85:626–627.

9. Fontana D, Porpiglia F, Morra I, Destefanis P. Treatment of simple renal cysts by percutaneous drainage with 3 repeated alcohol injection. Urology. 1999. 53:904–907.

10. Kim JH, Lee JT, Kim EK, Won JY, Kim MJ, Lee JD, et al. Percutaneous sclerotherapy of renal cysts with a beta-emitting radionuclide, holmium-166-chitosan complex. Korean J Radiol. 2004. 5:128–133.

11. Roberts WW, Bluebond-Langner R, Boyle KE, Jarrett TW, Kavoussi LR. Laparoscopic ablation of symptomatic parenchymal and peripelvic renal cysts. Urology. 2001. 58:165–169.

12. Falci-Junior R, Lucon AM, Cerri LM, Danilovic A, Da Rocha PC, Arap S. Treatment of simple renal cysts with single-session percutaneous ethanol sclerotherapy without drainage of the sclerosing agent. J Endourol. 2005. 19:834–838.

13. Yoder BM, Wolf JS Jr. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic decortication of peripheral and peripelvic renal and adrenal cysts. J Urol. 2004. 171(2 Pt 1):583–587.

14. Akinci D, Akhan O, Ozmen M, Gumus B, Ozkan O, Karcaaltincaba M, et al. Long-term results of single-session percutaneous drainage and ethanol sclerotherapy in simple renal cysts. Eur J Radiol. 2005. 54:298–302.

15. Lee YR, Lee KB. Ablation of symptomatic cysts using absolute ethanol in 11 patients with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Korean J Radiol. 2003. 4:239–242.

16. Gasparini D, Sponza M, Valotto C, Marzio A, Luciani LG, Zattoni F. Renal cysts: can percutaneous ehtanol injections be considered an alternative to surgery? Urol Int. 2003. 71:197–200.

17. Akhan O, Ozmen MN, Dincer A, Sayek I, Göcmen A. Liver hydatid disease: long-term results of percutaneous treatment. Radiology. 1996. 198:259–264.

18. Khuroo MS, Zargar SA, Mahajan R. Echinococcus granulosus cysts in the liver: management with percutaneous drainage. Radiology. 1991. 180:141–145.

19. Paksoy Y, Odev K, Sahin M, Arslan A, Koc O. Percutaneous treatment of liver hydatid cysts: comparison of direct injection of albendazole and hypertonic saline solution. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005. 185:727–734.

20. Harisinghani MG, Gervais D, Hahn PF, Jhaveri K, Yoder I, Mueller PR. CT and MR of atypical cystic renal masses: Revisiting the Bosniak classification. Radiologist. 2001. 8:145–153.

21. Warren KS, McFarlane J. The Bosniak classification of renal cystic masses. BJU Int. 2005. 95:939–942.

22. Nahm AM, Ritz E. The simple renal cyst. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000. 15:1702–1704.

23. Curry NS, Bissada NK. Radiologic evaluation of small and indeterminant renal masses. Urol Clin North Am. 1997. 24:493–505.

24. Higgins JC, Fitzgerald JM. Evaluation of incidental renal and adrenal masses. Am Fam Physician. 2001. 63:288–294. 299

25. Akinci D, Gumus B, Ozkan OS, Ozmen MN, Akhan O. Single-session percutaneous ethanol sclerotherapy in simple renal cysts in children: long-term follow-up. Pediatr Radiol. 2005. 35:155–158.

26. Yasuda M, Masai M, Shimazaki J. A simple renal cyst. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 1993. 84:251–257.

27. Dalton D, Neiman H, Grayhack JT. The natural history of simple renal cysts: a preliminary study. J Urol. 1986. 135:905–908.

28. Wolf JS Jr. Evaluation and management of solid and cystic renal masses. J Urol. 1998. 159:1120–1133.

29. Camacho MF, Bondhus MJ, Carrion HM, Lockhart JL, Politano VA. Ureteropelvic junction obstruction resulting from percutaneous cyst puncture and intracystic isophendylate injection: an unusual complications. J Urol. 1980. 124:713–714.

30. Bean WJ, Rodan BA. Hepatic cysts: treatment with alcohol. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985. 144:237–241.

31. Goktay AY, Secil M, Gulcu A, Hosgor M, Karaca I, Olguner M, et al. Percutaneous treatment of hydatid liver cysts in children as a primary treatment: long-term results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005. 16:831–839.

32. Kabaalioğlu A, Karaali K, Apaydin A, Melikoğlu M, Sindel T, Lüleci E. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous sclerotherapy of hydatid liver cysts in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000. 16:346–350.

33. Kabaalioğlu A, Apaydin A, Ozkaynak C, Melikoğlu M, Sindel T, Lüleci E. Percutaneous sclerotherapy of a symptomatic simple renal cyst in a child: observation of membrane detachment sign. Eur Radiol. 1996. 6:872–874.

34. Lin YH, Pan HB, Liang HL, Chung HM, Chen CY, Huang JS, et al. Single-session alcohol-retention sclerotherapy for simple renal cysts: comparison of 2- and 4-hr retention techniques. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005. 185:860–866.

35. De Dominicis C, Ciccariello M, Peris F, Di Crosta G, Sciobica F, Zuccalà A, et al. Percutaneous sclerotization of simple renal cysts with 95% ethanol followed by 24-48 h drainage with nephrostomy tube. Urol Int. 2001. 66:18–21.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download