Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the frequency and relevance of the "sentinel clot" sign on CT for patients with traumatic intraperitoneal bladder rupture in a retrospective study.

Materials and Methods

During a recent 42-month period, 74 consecutive trauma patients (45 men, 29 women; age range, 12-84 years; mean age, 50.8 years) with gross hematuria were examined by the use of intravenous contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis, followed by retrograde cystography. Contrast-enhanced CT scanning was performed by using a helical CT scanner. CT images were retrospectively reviewed in consensus by two radiologists. The CT findings including the sentinel clot sign, pelvic fracture, traumatic injury to other abdominal viscera, and the degree of intraperitoneal free fluid were assessed and statistically analyzed using the two-tailed χ2 test.

Results

Twenty of the 74 patients had intraperitoneal bladder rupture. The sentinel clot sign was seen for 16 patients (80%) with intraperitoneal bladder rupture and for four patients (7%) without intraperitoneal bladder rupture (p < 0.001). Pelvic fracture was noted in five patients (25%) with intraperitoneal bladder rupture and in 39 patients (72%) without intraperitoneal bladder rupture (p < 0.001). Intraperitoneal free fluid was found in all patients (100%) with intraperitoneal bladder rupture, irrespective of an associated intraabdominal visceral injury, whereas 19 (35%) of the 54 patients without intraperitoneal bladder rupture had intraperitoneal free fluid (p < 0.001).

The bladder is located deep within the pelvis and is protected by the pelvic bones, which explains why major bladder injury is relatively uncommon in patients suffering blunt abdominal trauma (1). Nevertheless, bladder rupture remains an important injury and delay in the diagnosis and treatment of a ruptured bladder may be associated with increased mortality (2).

Accurate classification of the type of bladder injury is important due to differences in the clinical management of the injuries (2-4). Extraperitoneal rupture can be managed conservatively with catheter drainage alone, whereas intraperitoneal bladder rupture requires immediate surgical repair to the bladder tear, because of the risk of fatal peritonitis. Patients with suspected bladder injuries are usually evaluated with retrograde cystography. Instead of retrograde cystography, many investigators have attempted to diagnose bladder rupture with CT cystography that has been shown to be as accurate as conventional cystography (2-6).

Bladder rupture after blunt abdominal trauma frequently occurs in multi-trauma patients (1). Because hemodynamically stable multi-trauma patients usually undergo abdominopelvic CT as part of their initial evaluation, it is useful to predict the presence of a possible intraperitoneal bladder rupture on CT scans. However, the use of abdominopelvic CT in the diagnosis of intraperitoneal bladder rupture has received little attention and a diagnosis of intraperitoneal bladder rupture is made according to the presence of contrast material extravasation from the bladder seen on the CT scans (7, 8).

The sentinel clot sign describes a relatively highly attenuating and heterogeneous fluid (clot) that tends to accumulate near the site of injury (9). We postulated the sentinel clot sign should be a specific CT finding for patients with traumatic intraperitoneal bladder rupture.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the frequency and relevance of the sentinel clot sign on abdominopelvic CT for patients with traumatic intraperitoneal bladder rupture in a retrospective review.

Our institutional review board approved all aspects of this retrospective study and did not require informed consent from the patients whose medical records were included in our study.

From January 2002 to June 2005, 74 consecutive trauma patients with gross hematuria were examined with intravenous contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis, followed by retrograde cystography. Retrograde cystography was performed between 1-12 hours (mean time: 4 hours) after the CT examination. This patient population was comprised of 45 men and 29 women (age range, 12-84 years; mean age, 50.8 years). All of the subjects were blunt abdominal trauma patients with one of the following mechanisms of injury: motor vehicle collision (n = 36); blow to lower abdomen (n = 16); pedestrian struck by a moving vehicle (n = 14); and fall (n = 8).

CT scanning was performed by using a helical scanner (HiSpeed Advantage: GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). Initially, an unenhanced CT scan was performed from the diaphragmatic dome to the symphysis pubis for the evaluation of the presence of an intraabdominal hematoma. Unenhanced CT images were obtained with 10-mm collimation, a pitch of 2, and 10-mm reconstruction interval. Contrast-enhanced CT then was performed after intravenous injection of 120-150 mL of 60% iodinated contrast material (Omnipaque 300, Nycomed Amersham, Princeton, NJ) with a power injector (LF CT 9000; Liebel-Flarsheim, Cincinnati, OH) at a rate of 3 mL/sec through an antecubital vein. Scanning was performed 70 seconds after the initiation of the contrast material injection from the diaphragmatic dome to the symphysis pubis. Contrast-enhanced CT images were obtained with 5-mm collimation, a pitch of 2, and 5-mm reconstruction interval. Multiplanar reformation images were obtained by using a software package (Advantage Workstation 4.0, GE Medical Systems).

Retrograde cystography was performed by the on-call urology resident and followed a standard protocol. Approximately 350-400 mL of water-soluble contrast material were instilled under gravity into the urinary bladder through a urethral catheter. Initially, anteroposterior and bilateral oblique views were obtained. The urinary bladder was then drained of all contrast material and an additional image on film was obtained.

The CT images were reviewed on a picture archiving and communication system workstation without knowledge of the retrograde cystographic findings. Multiplanar reformation images were used as an adjunct to the axial source images. The CT images were evaluated with respect to the "sentinel clot" sign, pelvic fracture, associated injury to other abdominal viscera, and the presence and quantity of intraperitoneal free fluid in consensus by two experienced radiologists. The sentinel clot sign was considered to be present when clotted blood (greater than 50 HU) abutted on the bladder dome. The amount of intraperitoneal free fluid was categorized as small, moderate, or large, according to the criteria of Federle and Jeffrey (10). Retrograde cystographic images were evaluated with respect to the presence and type of bladder injury in consensus by one experienced radiologist and one experienced urologist. Bladder injuries were classified into five types (bladder contusion, intraperitoneal rupture, interstitial bladder injury, extraperitoneal rupture, combined bladder injury), according to the criteria of Sandler et al. (11). Diagnosis and classification of bladder injury were established by means of retrograde cystography and surgery (n = 25), retrograde cystography and cystoscopy (n = 2), and retrograde cystography and clinical and imaging follow-up (n = 47).

Based on the CT findings, statistical differences between patients with intraperitoneal bladder rupture and patients without intraperitoneal bladder rupture were analyzed using the two-tailed χ2 test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS software package (version 10.0 for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

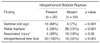

Of 74 patients, 36 patients had 36 bladder injuries: 20 injuries were intraperitoneal, 15 injuries were extraperitoneal, and one injury was interstitial. Table 1 summarizes the different CT findings for the patients with intraperitoneal rupture.

The sentinel clot sign was found in 16 (80%) of the 20 patients with intraperitoneal rupture (Figs. 1, 2) and in four (7%) of the 54 patients without intraperitoneal rupture. Four false-positive cases were noted among the 38 patients who did not have bladder injury and were caused by clotted blood from pelvic mesenteric injury (n = 2) and pelvic fracture (n = 2). In 20 patients with the CT depicted sentinel clot sign, the mean attenuation level of clotted blood was 59 HU, ranging from 52 to 68 HU. The sentinel clot sign was more frequently found in patients that were identified with intraperitoneal rupture (p < 0.001).

Five (25%) of the 20 patients with intraperitoneal rupture had one or more pelvic fractures, whereas 39 (72%) of the 54 patients without intraperitoneal rupture had one or more pelvic fractures. Pelvic fractures were more frequently found in patients without intraperitoneal rupture (p < 0.001). Eleven (73%) of the 15 patients with extraperitoneal rupture had one or more pelvic fractures. Twenty-eight (74%) of the 38 patients without bladder injury had one or more pelvic fractures. One patient with interstitial injury had no pelvic fractures.

An associated injury to other abdominal viscera was found in four (20%) of the 20 patients with intraperitoneal rupture. The sites of associated injury were as follows; liver (n = 2), bowel and mesentery (n = 2), and spleen (n = 1). In 16 patients with intraperitoneal rupture and a positivesentinel clot sign, no concomitant injury of structures adjacent to the bladder was found. In 54 patients without intraperitoneal rupture, an associated injury was found in 10 (18%) patients. The sites of associated injury were as follows; liver (n = 3); bowel and mesentery (n = 4), kidney (n = 3), spleen (n = 4), and pancreas (n = 1). In regards to an associated injury to other abdominal viscera, there was no significant difference between patients with intraperitoneal rupture and patients without intraperitoneal rupture (p = 0.885).

Intraperitoneal free fluid was found in 20 (100%) of the 20 patients with intraperitoneal rupture and in 19 (35%) of the 54 patients without intraperitoneal rupture. The quantity of intraperitoneal free fluid was small in one(5%), moderate in two (10%), and large in 17 (85%) of the 20 patients with intraperitoneal rupture. In 54 patients without intraperitoneal rupture, the quantity of intraperitoneal free fluid was categorized as none in 35 (64%), small in seven (13%), moderate in three (5%), and large in nine (16%) patients (Table 2). Intraperitoneal free fluid was more frequently found in patients with intraperitoneal rupture (p < 0.001) and these patients were more likely to have a large amount of intraperitoneal free fluid (p < 0.001).

Intraperitoneal bladder rupture constitutes about 10-40% of all bladder ruptures (12, 13). Intraperitoneal bladder rupture frequently occurs at the anatomically vulnerable bladder dome, the weakest and most mobile part of the bladder (13). It is more common with a full bladder and blunt abdominal trauma. A sudden rise in intravesicular pressure secondary to a blow to the pelvis or lower abdomen causes intraperitoneal rupture of the bladder dome (2).

The bladder is a highly vascular organ and its rupture is usually associated with gross hematuria (1). In addition, the majority of intraperitoneal bladder rupture consists of large lacerations of the bursting type in the bladder dome (7). Thus, high attenuating blood clots can be found around the bladder dome. Clotted blood, which has a mean attenuation of 50 HU, has a higher attenuation coefficient than a lysed blood clot or free-flowing blood because of the greater hemoglobin content (9, 10). In our study, the attenuation of clotted blood on CT images ranged from 52 to 68 HU, which allowed a clear separation between clotted blood and surrounding fluid. Orwig and Federle (9) have reported that the sentinel clot sign was a valuable adjunct in CT of abdominal trauma, being both sensitive and specific in identifying the injured organ. The results of our study show that the presence of a sentinel clot abutting on the bladder dome is helpful in predicting intraperitoneal bladder rupture for blunt abdominal trauma victims.

In this study there were four false-positive cases and four false-negative cases. The four false-positive findings were caused by clotted blood from sites other than the bladder. One limitation of CT in detecting the sentinel clot sign is that any clotted blood from various injured organs, which abut on the bladder dome, could be interpreted as arising from the ruptured bladder. Although a reason why the sentinel clot sign was not seen in the four patients with intraperitoneal bladder rupture is not apparent, in our opinion a small amount of bleeding at the time of impact and a delay in performing the CT examination after blunt trauma seem to be the related factors.

Pelvic fracture is a common associated injury in patients with bladder rupture. However, only 9% to 16% of patients sustaining pelvic fractures have bladder injuries, and these are predominantly extraperitoneal (14). In our study, 15 (75%) of 20 patients with intraperitoneal rupture had no pelvic fracture. It is important to remember that the absence of a pelvic fracture does not exclude bladder rupture, especially an intraperitoneal rupture (15).

It has been reported that the presence of intraperitoneal free fluid without evidence of solid organ injury may indicate injury to the bowel or mesentery (16-18). However, unexplained free fluid does not always mean the presence of bowel or mesenteric injury in patients sustaining blunt abdominal trauma. According to a study by Cunningham et al. (18), intraperitoneal bladder rupture constituted the third most common cause following bowel or mesentery injury in patients with unexplained free fluid after blunt abdominal trauma. In our study, 16 (80%) of the 20 patients with intraperitoneal bladder rupture had intraperitoneal free fluid without an associated solid organ injury or bowel and mesentery injury. Thus, intraperitoneal bladder rupture in patients sustaining blunt abdominal trauma seems to be strongly associated with the presence of intraperitoneal free fluid.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study and might have a selection bias. Wedid not include patients who underwent a CT examination after retrograde cystography because the blood clot could be replaced or could be masked by the leaked contrast material. Second, there was no uniform surgical proof of the findings because most of patients with extraperitoneal bladder rupture were not subjected to surgery. Finally, we did not compare contrast material extravasation from the bladder with the presence of the sentinel clot sign as a diagnostic criterion for intraperitoneal bladder rupture as delayed contrast-enhanced CT scans were not obtained.

In conclusion, the sentinel clot sign abutting on the bladder dome resulted in a high likelihood of intraperitoneal bladder rupture. The sentinel clot sign may improve the accuracy of CT performed before cystography in diagnosing traumatic intraperitoneal bladder rupture, especially when the patients present with gross hematuria.

Figures and Tables

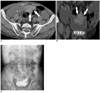

Fig. 1

An 84-year-old man with an intraperitoneal bladder rupture.

A. A transverse unenhanced CT image shows a high-attenuating hematoma (arrows) with an attenuation of 57 HU abutting on the bladder dome filled with low-attenuating fluid (arrowheads).

B. A coronal reformatted CT image clearly depicts a high-attenuating hematoma (arrows) on the bladder.

C. A conventional cystogram obtained with the patient in the supine position shows extravasation of contrast material into the intraperitoneal space.

Fig. 2

A 51-year-old man with an intraperitoneal bladder rupture.

A. A transverse contrast-enhanced CT image shows a high-attenuating hematoma (arrows) with an attenuation of 59 HU abutting on the collapsed bladder dome (arrowheads).

B. A coronal reformatted CT image clearly depicts a high-attenuating hematoma (arrows) on the bladder (arrowheads).

C. A conventional cystogram obtained with the patient in the supine position shows extravasation of contrast material into the intraperitoneal space.

Table 2

Amount of Intraperitoneal Free Fluid Correlated with Intraperitoneal Bladder Rupture

Note.-*According to Federle and Jeffrey (10)

References

1. Morey AF, Iverson AJ, Swan A, Harmon WJ, Spore SS, Bhayani S, et al. Bladder rupture after blunt trauma: guidelines for diagnostic imaging. J Trauma. 2001. 51:683–686.

2. Vaccaro JP, Brody JM. CT cystography in the evaluation of major bladder trauma. RadioGraphics. 2000. 20:1373–1381.

3. Power N, Ryan S, Hamilton P. Computed tomographic cystography in bladder trauma: pictorial essay. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2004. 55:304–308.

4. Corriere JN Jr, Sandler CM. Diagnosis and management of bladder injuries. Urol Clin North Am. 2006. 33:67–71.

5. Peng MY, Parisky YR, Cornwell EE 3rd, Radin R, Bragin S. CT cystography versus conventional cystography in evaluation of bladder injury. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999. 173:1269–1272.

6. Kane NM, Francis IR, Ellis JH. The values of CT in the detection of bladder and posterior urethral injuries. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989. 153:1243–1246.

7. Haas CA, Brown SL, Spirnak JP. Limitations of routine spiral computerized tomography in the evaluation of bladder trauma. J Urol. 1999. 162:51–52.

8. Pao DM, Ellis JH, Cohan RH, Korobkin M. Utility of routine trauma CT in the detection of bladder rupture. Acad Radiol. 2000. 7:317–324.

9. Orwig D, Federle MP. Localized clotted blood as evidence of visceral trauma on CT: the sentinel clot sign. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989. 153:747–749.

10. Federle MP, Jeffrey RB. Hemoperitoneum studied by computed tomography. Radiology. 1983. 148:187–192.

11. Sandler CM, Hall JT, Rodriguez MB, Corriere JN. Bladder injury in blunt pelvic trauma. Radiology. 1986. 158:633–638.

12. Wah TM, Spencer JA. The role of CT in the management of adult urinary tract trauma. Clin Radiol. 2001. 56:268–277.

13. Gomez RG, Ceballos L, Coburn M, Corriere JN Jr, Dixon CM, Lobel B, et al. Consensus statement on bladder injuries. BJU Int. 2004. 94:27–32.

14. Brandes S, Borrelli J Jr. Pelvic fracture and associated urologic injuries. World J Surg. 2001. 25:1578–1587.

15. Morgan DE, Nallamala LK, Kenney PJ, Mayo MS, Rue LW 3rd. CT cystography: radiographic and clinical predictors of bladder rupture. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000. 174:89–95.

16. Rodriguez C, Barone JE, Wilbanks TO, Rha CK, Miller K. Isolated free fluid on computed tompgraphic scan in blunt abdominal trauma: a systematic review of incidence and management. J Trauma. 2002. 53:79–85.

17. Ng AK, Simons RK, Torreggiani WC, Ho SG, Kirkpatrick AW, Brown DR. Intra-abdominal free fluid without solid organ injury in blunt abdominal trauma: an indication for laparotomy. J Trauma. 2002. 52:1134–1140.

18. Cunningham MA, Tyroch AH, Kaups KL, Davis JW. Does free fluid on abdominal computed tomographic scan after blunt trauma require laparotomy? J Trauma. 1998. 44:599–603.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download