Abstract

A 12-week-old baby with a vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation (VGAM) was successfully treated with performing transarterial microcatheter-directed embolization with Berenstein Liquid Coils and n-butyl cyanoacrylate in the feeding arteries. Post-procedure angiography showed a marked decrease of the blood flow into the dilated vein of Galen. Three months later, follow-up angiography showed that the vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation had totally disappeared, and the baby recovered very well without any sequelae. We report here on this interesting case along with a review of the relevant literature, and we aim to enhance physicians' awareness of the treatment for VGAMs.

Vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation (VGAM) is a rare congenital intracranial vascular malformation in neonates. Dilatation of the vein of Galen is a common feature of the malformation (1-3). It is the result of an abnormal communication between one or several cerebral arteries and the vein of Galen that forces blood from the cerebral arteries into a dilated vein of Galen. These vessels are deeply located in the brain. An endovascular approach offers the best possible approach to accessing the deep brain vessels (3, 4). Here, we describe one case of VGAM in which various imaging modalities were used for making the diagnosis and then transarterial microcatheter-directed embolization was performed.

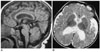

A male infant (3 kg, primi-gravida), was delivered vaginally without complications following a normal pregnancy. The ultrasound scan at 35 weeks of gestation showed an irregular volume of liquid anechoic space in the midline of the brain. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the infant's head conducted done three days after birth showed a vein aneurysm in the brain. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging was also performed, and it showed a large area of flow void along the course of the deep vein and a marked supertentorial hydrocephalus (Fig. 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of VGAM was made and elective endovascular treatment was planned.

This neonate was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation and VGAM treatment was planned at 12 weeks of age. He presented as a well-developed, wellnourished baby. Physical examination revealed nothing abnormal. There were no engorged scalp veins. His head circumference was 37 cm. The fontanels were 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm. The results of all other examinations were normal, including the haemoglobin, complete blood count, renal and liver function tests and the coagulation profile. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed evidence of biventricular hypertrophy, and echocardiography revealed a patent foramen ovale. The results of digital substraction angiography (DSA) performed under general anaesthesia confirmed the CT and MRI findings. Blood was being supplied to the VGAM from the bilateral posterior cerebral arteries and their branches, and it drained into the straight sinus with high blood flow (Fig. 2). Therapeutic embolization was subsequently done through an arterial approach. After the placement of a microcatheter (Tracker-10; Boston Scientific, Fremont, CA) on the distal part of the right feeding artery, the embolization was first performed with placing two Berenstein Liquid Coils-10 (Boston Scientific, New York, NY) in the feeding arteries, and this was followed by slow injection of a mixture of n-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA; B. Braum Melsnagen, Germany) and lipiodol (Guerbet; Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France) at a ratio of 1:2 (NBCA:Lipiodol = 1:2). A total of 0.4 ml of the embolic mixture was injected. The process was repeated in the left feeding arteries. Post-procedure angiography displayed an immediate decrease in the size of the VGAM and a marked decrease of blood flow through the fistulas (Fig. 3). Three months after therapeutic intervention, the follow-up angiography that was done via both bilateral internal carotid arteries and the left vertebral artery showed that the VGAM had totally disappeared together with the thrombosis of the straight sinus (Fig. 4). MR imaging showed the reversal of hydrocephalus without any abnormal growth of the brain parenchyma (Fig. 5). The baby recovered well without any apparent sequelae.

Vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation is a rare congenital vascular malformation that is characterized by shunting of the arterial flow into an enlarged cerebral vein of Galen (1-3). Although the cases of VGAM constitute only 1% of all cerebral vascular malformations, they comprise up to 30% of all paediatric vascular malformations (1). The arteries feeding the VGAM are the posterior cerebral artery, the choroidal arteries and the posterior perforating artery.

Vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation is believed to result from an insult to the cerebral vasculature at between six and 11 weeks of gestation after the development of the circle of Willis (2, 5). It is also thought to result from the development of an arteriovenous connection between the primitive choroidal vessels and the median prosencephalic vein of Markowski (5). The abnormal flow through this connection interferes with the normal development of the vein of Galen. The shunt is maintained through a later period of brain development, with the persistent median vein draining into the sagittal sinus and often via a persistent falcine vein. Other venous anomalies commonly co-occur with VGAMs, including anomalous dural sinuses, sinus stenoses and an absence of the straight sinus (2, 5). These anomalies commonly present during the neonatal period, although they may appear during early childhood as well.

Since VGAMs lack capillaries, blood drains directly into a single deep draining vein. The blood flow can be fast, increasing the work load of the heart and the risk of heart failure (1, 6). The associated congenital heart diseases include patent ductus arteriosus, patent foramen ovale, sinus venosus and atrial septal defects, partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage to the superior vena cava and aortic coarctation (1, 7), and these maladies may be diagnosed instead of VGAM. However, making an accurate and early diagnosis of VGAM is very important. The high flow of blood can also interfere with the normal venous drainage of the brain, potentially causing hydrocephalus (8). Alternatively, the VGAM may obstruct the flow of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), resulting in hydrocephalus. In addition, a certain degree of developmental delay can be a major problem during the neonatal presentation of these infants. As these infants have congestive heart failure, they have physical developmental delays and because of the CNS problems, neurologic developmental delays as well.

The overall mortality associated with VGAM is 26% (2). Surgical ligation of the fistula and radiotherapy are sometimes performed due to the high morbidity and mortality rates (1, 3). Endovascular procedures, either by transarterial or transvenous routes, have recently been used as a definitive or adjunct treatment (1, 3, 4). The transarterial approach is performed using microcatheter delivery systems, which may achieve superselective embolization of the fistulous connection. Transarterial embolization is more effective when there is only one or a limited number of arterial pedicles. However, when there are numerous small arterial feeders, it is often impossible to achieve occlusion of a VGAM via the transarterial route. In these cases, it is believed that transvenous embolization offers a greater chance of temporarily controlling any existing heart failure (6). The transvenous approach is performed through either an operatively exposed torcula or a transfemoral venous catheter. Large metal coils are deposited in the aneurysmal vein of Galen to reduce the arteriovenous shunting. The transvenous approach can be easily repeated several times and this may be supplemented by transarterial embolizations. For the VGAMs with high flow, NBCA should be injected carefully through arteries into the inner VGAM in order to avoid the NBCA flowing into the venous route. Solid materials such as microcoils, microballoons and silk sutures have been used to embolize these vessels, and these materials have achieved variable success. The liquid adhesives that have been used for embolization include cyanoacrylate monomers like NBCA and ethylene such as ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (10). The Berenstein Liquid Coil can be used for embolization of some vascular lesions (11), but it was more dangerous to use in a large and high flow shunt as compared with the use of detachable coils because it may cause inappropriate embolization of the cerebral venous system or pulmonary embolization. Considering the stenosis and tortuosity at the terminal portion of the feeding artery in our case, we chose the Berenstein Liquid Coil for reducing the high flow of the shunt instead of using a detachable coil.

This report describes the effective process of transarterial embolization with using Berenstein Liquid Coils and NBCA for the treatment of VGAMs. In this case study, various imaging modalities were used diagnostically prior to performing transarterial microcatheter-directed embolization. The patient recovered without any apparent sequelae. When considering the reports in the relevant literature, this approach appears to be a favorable option for the treatment of VGAMs.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

MR images (A. sagittal, T1-weighted image; B. axial, T2-weighted image) show a dilated vein of Galen with hydrocephalus.

Fig. 2

Angiography shows a vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation that is supplied from the bilateral posterior cerebral arteries and their branches (A. right internal carotid artery; B. left internal carotid artery; C. left vertebral artery).

Fig. 3

A. Plain film just after the injection of Berenstein Liquid Coils and n-butyl cyanoacrylate shows an inhomogenous distribution of radiopaque glue and free coils into the vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation. Angiography just after embolization (B. right internal carotid artery; C. left internal carotid artery) shows a marked decrease of flow into the vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation.

References

1. Johnston IH, Whittle IR, Besser M, Morgan MK. Vein of Galen malformation: diagnosis and management. Neurosurgery. 1987. 20:747–758.

2. Jones BV, Ball WS, Tomsick TA, Millard J, Crone KR. Vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation: diagnosis and treatment of 13 children with extended clinical follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002. 23:1717–1724.

3. Lasjaunias P, Garcia-Monaco R, Rodesch G, Ter Brugge K, Zerah M, Tardieu M, et al. Vein of Galen malformation. Endovascular management of 43 cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 1991. 7:360–336.

4. Dowd CF, Halbach VV, Barnwell SL, Higashida RT, Edwards MS, Hieshima GB. Transfemoral venous embolization of vein of Galen malformations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1990. 11:643–648.

5. Raybaud CA, Strother CM, Hald JK. Aneurysm of the vein of Galen: embryonic considerations and anatomical features relating to the pathogenesis of the malformation. Neuroradiology. 1989. 31:109–128.

6. Stanbridge Rde L, Westaby S, Smallhorn J, Taylor JF. Intracranial arteriovenous malformation with aneurysm of the vein of Galen as cause of heart failure in infancy. Echocardiographic diagnosis and results of treatment. Br Heart J. 1983. 49:157–162.

7. McElhinney DB, Halbach VV, Silverman NH, Dowd CF, Hanley FL. Congenital cardiac anomalies with vein of Galen malformations in infants. Arch Dis Child. 1998. 78:548–551.

8. Pun KK, Yu YL, Huang CY, Woo E. Ventriculo-peritoneal shunting of acute hydrocephalus in vein of Galen malformation. Clin Exp Neurol. 1987. 23:209–212.

9. Baenziger O, Martin E, Willi U, Fanconi S, Real F, Boltshauser E. Prenatal brain atrophy due to a giant vein of Galen malformation. Neuroradiology. 1993. 35:105–106.

10. Yang HJ, Choi YH. Posttraumatic pseudoaneurysm in scalp treated by direct puncture embolization using N-Butyl-2-cyanoacrylate: a case report. Korean J Radiol. 2005. 6:37–40.

11. Ha-Kawa SK, Kariya H, Murata T, Tanaka Y. Successful transcatheter embolotherapy with a new platinum microcoil: the Berenstein Liquid Coil. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1998. 21:297–299.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download