Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the ultrasonographic (US) findings of rupture and the healing process of the medial head of the gastrocnemius ("Tennis Leg").

Materials and Methods

Twenty-two patients (age range: 30 to 45 years) with clinically suspected ruptures of the medial head of the gastrocnemius were referred to us for US examination. All the patients underwent US of the affected limb and the contralateral asymptomatic limb. Follow-up clinical evaluation and US imaging of all patients were performed at two-week intervals during the month after injury and at one-month intervals during the following six months.

Results

Of the 22 patients who had an initial US examination after their injury, partial rupture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle was identified in seven patients (31.8%); the remaining 15 patients were diagnosed with complete rupture. Fluid collection between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle was identified in 20 patients (90.9%). The thickness of the fluid collection, including the hematoma in the patients with complete rupture (mean: 9.7 mm), was significantly greater than that seen in the patients with partial tear (mean: 6.8 mm) (p < 0.01). The primary union of the medial head of the gastrocnemius with the soleus muscle in all the patients with muscle rupture and fluid collection was recognized via the hypoechoic tissue after four weeks.

Rupture of the distal musculotendinous junction of the medial head of the gastrocnemius is also called "tennis leg", and it is a relatively common clinical condition. The classic clinical manifestation is that of a middle-aged person who complains of acute sports-related pain in the middle portion of the calf that is associated with a snapping sensation (1). The patients are usually injured when performing active plantar flexion of the foot with simultaneous extension of the knee, which implies simultaneous active contraction and passive stretching of the gastrocnemius (2). Ultrasonography (US) has been used as the primary imaging technique for evaluating the patients suffering with this clinical condition (3, 4). This muscle injury is generally managed conservatively with a nonoperative protocol of ice, elevation, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications and neoprene case sleeves (5, 6). However, recovery of their previous pain-free activity level may take several months (5). Also, the follow-up examination by US after this muscle injury shows a hypoechoic area interposed between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle, and this probably corresponds to fibrous tissue (3). In this report, we present our experience with the US findings and the correlation between the clinical symptoms and the follow-up ultrasonographic findings for the patients suffering with ruptures of the distal musculotendinous junction of the medial head of the gastrocnemius.

The study subjects were twenty-nine consecutive patients who were seen at a Korean military hospital and they were referred to our department for an US examination with the clinical diagnosis of rupture of the musculotendinous junction of the medial head of the gastrocnemius; these 29 subjects were seen between May 2002 and March 2004. Prospective analysis of the clinical symptom and US was done for these patients. Of the 29 patients, seven were excluded from this study because they didn't suffer muscle rupture (n = 4) or they were lost to follow-up (n = 3). The remaining 22 patients were included in this study (age range: 30 to 45 years; mean age: 39). All the patients were male. The institutional review board of our hospital approved this study, and a written informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

The patients had acute, posttraumatic calf pain that occurred subsequent to such intense sports activity as football (n = 16) and tennis (n = 6). The patients came to the hospital at an average of 1.5 days (range: 1-4 days) after the onset of their clinical symptoms.

The US examinations were performed with using 12 MHz broad-band electronic linear array probes (ATL HDI 3000). One radiologist (H-S.K.) performed the first examinations at a single institution. The patients were placed in the prone position to emphasize the longitudinal and transverse planes for the analysis. Stand-off pad were not used. In each case, the opposite lower extremity was also examined for making a comparison. US of the normal limbs showed the muscle fibers of the medial head and fibroadipose septa as being regularly organized parallel hypoechoic and hyperechoic lines ending in the muscle aponeurosis. We (H-S.K. and K-N.K.) conducted a prospective review to analyze the partial and complete muscle ruptures, and the diagnosis of a partial muscle rupture was based on the presence of a localized disruption or discontinuity of the muscular fibers, whereas a complete rupture was defined as a lesion that involved the entire muscle (4). Fluid collection with/without hemorrhage at the heterogeneous echogenicity between the aponeurosis of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles was defined as abnormal echogenicity at this location. The measurement of fluid collection was considered as the greatest distance of separation between the two muscles. The degrees of fluid collection after partial or complete rupture were analyzed during the follow-up period. The Student t-test was used for statistical analysis (SPSS version 10.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL). A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The treatment, clinical evaluation and US evaluation during the follow-up period of all patients was performed with the following protocol; they received ice, rest, leg elevation and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs within the first 1-2 days after the muscle ruptures, and then each patient received a crutch and a neoprene cast sleeve to be worn for 2-4 weeks. This was followed by a passive and active stretching program for two weeks. The patients whose symptoms disappeared had their neoprene cast sleeve removed and they performed an early stretching program. Follow-up clinical evaluation and US evaluation of all the patients were done at two-week intervals during the first month of their injury and then at one-month intervals during the following six months. The amount of fluid collection after the initial injury was defined as the distance of the widely separate area between the two muscles on the longitudinal scanning during the US examination. Also, the primary union between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle was defined as a beginning of the appearance of reparative tissue at the musculotendinous junction between the two muscles during the follow-up period. The clinical healing time was defined as the length of time until the patient could walk without feeling pain. Also, US imaging was used to analyze the change in the fluid collection and the reparative process of the muscle ruptures during the follow-up period.

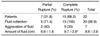

As noted on the US examination, all the patients experienced disruption of the normal regular linear hyperechoic and hypoechoic appearance of the tendon at the origin site of the medial head of the gastrocnemius, and this was accompanied by the indistinct appearance of the tapering distal end of the tendon at its insertion. The results of the 22 patients on the initial US examination after injury are shown in Table 1. On the initial US examinations of the 22 patients after injury, partial rupture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius was identified in seven patients (31.8%) (Fig. 1A). Of these seven patients, five had an associated fluid collection between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle (71.4%). The remaining 15 patients were diagnosed as having complete rupture, and they had fluid collections between the two muscles (Fig. 2A). These fluid collections showed evident hematoma that appeared as a fusiform heterogeneous area between the disrupted medial head of the gastrocnemius and the aponeurosis of the soleus. The degrees of the fluid collection after muscle injury were from 4-16 mm (mean: 8.2). The degrees of the fluid collection in the patients with complete rupture (6-16 mm; mean: 9.7) were significantly greater than that in patients with partial rupture (4-8; mean: 6.8) (p < 0.05).

Of the five patients with partial rupture and fluid collection, two patients showed a greater aggravated fluid collection on the follow-up imaging at a 2-week interval after injury than was identified on the initial findings (Figs. 1B, C). For two patients with small tears, but no fluid collection, the distal portion of the medial head of the gastrocnemius revealed that the muscle fibers and septa did not reach the aponeurosis. One of these two patients showed fluid collection on the follow-up examination two week following the injury. One patient without fluid collection was clinically asymptomatic two week following the injury. Of the 15 patients with complete rupture, five of them experienced increased fluid collection between the two muscles at two-weeks following injury.

The follow-up US examinations two weeks later showed the reparative process as a hypoechoic area starting from the periphery of the fluid collection and this gradually proceeded toward its center, while the amount of the central fluid decreased in size (Figs. 2B, C). The primary union of the musculotendinous junction between the two muscles of all patients with muscle rupture and fluid collection appeared as heterogeneous hypoechoic tissue at the distal musculotendinous junction of the medial head of the gastrocnemius after four weeks (Fig. 2B). All the patients were able to walk after primary union of the distal musculotendinous junction of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle. The time interval from the initial injury to forming a union was not significantly different between the group with partial rupture and the group with complete rupture.

On the last six-months follow-up US examination of the 21 patients who showed an initial fluid collection, 12 patients, including the two patients with partial rupture and fluid collection, had a central anechoic fluid portion and a thick heterogeneous hyperechoic area of reparative tissue (Fig. 2D). The remaining nine patients had complete union of the tear that showed as a hyperechoic area; this corresponded to the fibrous tissue interposed between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle. All the patients were clinically asymptomatic at the six months follow-up, excluding the one patient with muscle rupture at the same location that was caused by running at two months.

Rupture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius is known as "tennis leg", and it is a relatively common clinical condition. It typically occurs when the muscle is overstretched by dorsiflextion of the ankle with the knee in full extension (1). This condition frequently occurs in the middle-aged, poorly conditioned patient who is engaged in strenuous physical activity (2, 5). A sudden pain is felt in the calf, and the patients often report an audible or palpable "pop" in the medial aspect of the posterior calf, or they have a feeling as though someone has kicked the back of their leg. Most patients who come to the hospital because of this condition develop substantial pain and swelling during the first 24 hours following their injury. In our study, patients were examined in the hospital at an average of 1.5 days following their injury. The physical examination immediately after the injury reveals a palpable defect in the medial belly of the gastrocnemius just above the musculotendinous junction. Patients are frequently unable to do a single-leg toe raise with the affected extremity and they have decreased power upon plantar flexion.

Although these clinical findings are believed to be characteristic of a tear of the medial head of the gastrocnemius, this condition is frequently confused with deep-vein thrombosis or thrombophlebitis of the lower extremity. Anticoagulation therapy, if it's undertaken before confirmation of the true diagnosis, can have serious adverse consequences, including severe hemorrhage, hematoma or compartment syndrome (7-9). Using an imaging modality can allow the physician to confirm the clinical suspicion of muscle tear, exclude other diseases and allow assessment of the size of the lesion; all of these things have an influence on the choice and duration of treatment (3, 4). US has proved to be successful for the evaluation of muscle trauma, including partial and complete muscle ruptures.

US examination of the muscle rupture is easy to perform, painless and can be done quickly. The normal distal medial gastrocnemius muscle tapers superficially to the soleus muscle. The soleus, together with the lateral gastrocnemius muscle, forms the Achilles tendon. The plantaris tendon can be visualized between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle. A rupture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius is characterized by disruption of the normal parallel linear hyperechoic and hypoechoic appearance of the tendon at its insertion, and this finding is typically accompanied with indistinctness of the tapering distal end of the tendon at its insertion (3, 4). The axial US image, in which the entire medial head is usually depicted in the same plane, was the most useful image for differentiating the partial lesions from complete lesions. Delgado et al. (4) reported two cases of plantaris tendon ruptures that were diagnosed on US examination. The US findings showed total discontinuity of the plantaris tendon, which was retraced proximally. The tendon tears were found distal to the musculotendinous junction; these have been found to occur in isolation (10, 11) and to be related with tennis leg.

Of our 22 study patients, 20 (90.9%) displayed a collection of fluid between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscles. The remaining two patients who were without any fluid collection were clinically asymptomatic for two weeks following their injury. Fluid collection between the two muscles has been noted in the cases of disruption of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle (3, 4, 12) as well as in the cases of plantaris rupture, especially at the level of the muscle belly or the musculotendinous junction (10, 11, 13). This fluid is considered to most likely represent a hematoma, which is usually seen as heterogeneous mixed echogenicity on the initial US examination after muscle injury (3). These fluids are slowly absorbed and then replaced by reparative tissues. In our study, the degree of fluid collection in the patients with complete rupture was larger than that of the fluid collection in the patients with partial rupture. Also, of the 20 patients with fluid collection on the initial US examination, seven of them (35.0%) had an increased amount of fluid collection on their follow-up examinations. Although the fluid collection was almost entirely evacuated, as shown by simultaneous US examination, the two-week follow up showed recurrence of nearly the same amount of fluid (3). In our study, of the five patients with partial rupture and fluid collection, two patients had an aggravated fluid collection that was greater at the time of the follow-up US examinations than that identified on the initial findings. Also, of the two patients who had small tears and no fluid collection, one showed fluid collection on the follow-up examination at two-week after the injury. These findings appeared because of the delayed fluid collection after the initial injury. Therefore, we think that early treatment is important for decreasing the collected fluid after injury.

The treatment for this condition is usually conservative, i.e., ice, elevation, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, heel pads and neoprene case sleeves, and this is followed by a passive stretching program for two weeks after the injury (5). Surgical treatment (fasciotomy) is indicated only when an associated compartmental syndrome has complicated the evolution of the signs and symptoms (1). Our treatment protocol is ice, rest, leg elevation and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs within the first 1-2 days following muscle ruptures, and then the patient uses a crutch and a neoprene cast sleeve for 2-4 weeks; this is followed by a passive and active stretching program for another two weeks.

Healing of a muscle rupture occurs slowly, and it takes three to 16 weeks to be completed. At a mean of 27 months after tennis leg injury, there was no statistically significant difference in the plantar flexion strength between the injured and non-injured limbs (6). Affected athletes should not resume their previous activity level until ambulation without pain is possible, i.e. approximately four to 12 weeks, depending on the extent of the tear (6). After the initial evaluation, the role of US is to determine the stage of healing. The follow-up US examinations show the reparative process as a hypoechoic area that starts from the periphery of the fluid collection and gradually proceeds toward the center.

In our study, the primary union of the two muscles of the patients suffering with muscle rupture and fluid collection appeared as the hypoechoic tissue at the distal musculotendinous junction of the medial head of the gastrocnemius after four weeks. It was usually possible for the patient to walk without pain, and at this time, there was usually union between the distal musculotendinous junction of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle. Therefore, we thought that the clinical healing time and the union of the distal musculotendinous junctions were consistent. Also, the last follow-up US examinations six months after the injuries showed a decrease in the amount of central fluid. All the patients were clinically asymptomatic, excluding for the one with a muscle rupture at the same location that was caused by running after two months.

Our study had some limitations. No confirmation of the US findings was obtained by surgery or by using other imaging modalities. No surgical therapy was performed because the patient care given by our medical and physical therapy departments was adequate and successful for all the patients. No patients underwent MR imaging because of its high cost and low availability.

In conclusion, for the patients with clinically suspected rupture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius, US imaging proved to be an easily performed, fast and a safe imaging modality. In our study, the primary union that was achieved via the hypoechoic tissue between the distal end of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle made it possible for the patients to walk freely and without pain. Therefore, the hypoechoic tissue between the distal end of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle, as demonstrated by US, will be the reliable sign of the primary union of the musculotendinous junction, and this will enable the clinicians to recommend early normal ambulation to the patients.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1A 35-year-old male with a partial rupture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius at the musculotendinous junction.

A. The longitudinal US image shows the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle with partial discontinuity of the muscle fibers (double arrows). A small hypoechoic fluid collection (single arrow) is noted. G = gastrocnemius muscle, S = soleus muscle.

B. The longitudinal US image one-week later shows a hyperechoic fluid collection (arrows). This fluid can be considered as most likely representing flesh blood.

C. The longitudinal US image four weeks later shows the reparative process as a hypoechoic area (arrows) and a well-defined anechoic fluid collection.

|

| Fig. 2A 31-year-old male with complete rupture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius at the musculotendinous junction.

A. The longitudinal US image obtained one day after the injury shows a poorly defined large fluid collection that separates the medial head of the gastrocnemius from the soleus muscle. G = gastrocnemius muscle, S = soleus muscle.

B. The longitudinal US image obtained four weeks later shows union of the hypoechoic tissue between the distal ends of the medial head of the gastrocnemius with the soleus muscle (arrows).

C. The longitudinal US image obtained three months following the injury shows the reparative process (arrows) as a hypoechoic area starting from the periphery of the fluid collection.

D. The longitudinal US image obtained six months following injury shows the healing of the rupture as heterogeneous echogenicity (arrows) that corresponds to fibrous tissue interposed between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle.

|

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Bonnie Hami, MA, Department of Radiology, University Hospital of Cleveland, for her editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Notes

References

1. Gilbert TJ Jr, Bullis BR, Griffiths HJ. Tennis calf or tennis leg. Orthopedics. 1996. 19:179.

2. Miller WA. Rupture of the musculotendinous juncture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle. Am J Sports Med. 1977. 5:191–193.

3. Bianchi S, Martinoli C, Abdelwahab IF, Derchi LE, Damiani S. Sonographic evaluation of tears of the gastrocnemius medial head ("tennis leg"). J Ultrasound Med. 1998. 17:157–162.

4. Delgado GJ, Chung CB, Lektrakul N, Azocar P, Botte MJ, Coria D, et al. Tennis leg: clinical US study of 141 patients and anatomic investigation of four cadavers with MR imaging and US. Radiology. 2002. 224:112–119.

5. Shields CL Jr, Redix L, Brewster CE. Acute tears of the medial head of the gastrocnemius. Foot Ankle. 1985. 5:186–190.

6. Blue JM, Matthews LS. Leg injuries. Clin Sports Med. 1997. 16:467–478.

7. Anouchi YS, Parker RD, Seitz WH Jr. Posterior compartment syndrome of the calf resulting from misdiagnosis of a rupture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius. J Trauma. 1987. 27:678–680.

8. McClure JG. Gastrocnemius musculotendinous rupture: a condition confused with thrombophlebitis. South Med J. 1984. 77:1143–1145.

9. Straehley D, Jones WW. Acute compartment syndrome (anterior, lateral, and superficial posterior) following tear of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 1986. 14:96–99.

10. Helms CA, Fritz RC, Garvin GJ. Plantaris muscle injury: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1995. 195:201–203.

11. Hamilton W, Klostermeier T, Lim EV, Moulton JS. Surgically documented rupture of the plantaris muscle: a case report and literature review. Foot Ankle Int. 1997. 18:522–523.

12. Bencardino JT, Rosenberg ZS, Brown RR, Hassankhani A, Lustrin ES, Beltran J. Traumatic musculotendinous injuries of the knee: diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiographics. 2000. 20:S103–S120.

13. Leekam RN, Agur AM, McKee NH. Using sonography to diagnosis injury of plantaris muscle and tendons. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999. 172:185–189.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download