Primary intraventricular hemorrhage, a nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage confined to the ventricular system, is uncommon. Intraventricular bleeding is more often observed as a secondary hemorrhage complicating a parenchymal hemorrhage originating near the ventricles (1). Most intraventricular meningiomas of the lateral ventricles originate in the trigones of these cavities. Acute intraventricular hemorrhage in patients with lateral ventricular meningioma is exceedingly rare, though a few cases of lateral ventricular meningioma presenting with hemorrhage have been described in the literature (2-4). We report a case of intraventricular hemorrhage attributable to intraventricular meningioma.

CASE REPORT

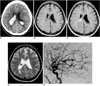

A 43-year-old woman was admitted with sudden headache associated with nausea and vomiting. There was no history of head trauma. Blood pressure on admission was 170/100 mmHg and neurologic examination was unremarkable. An initial CT scan (Fig. 1A) showed a well-defined, dense, calcified mass, combined with intraventricular hemorrhage in the trigone of the right lateral ventricle, and another dense calcified mass was present in the trigone of the left lateral ventricle. Mild ventricular distension was also observed. On T1-weighted MR images (Figs. 1B and 1C) obtained on the same day, the mass in the right lateral ventricle was seen as almost iso intense relative to the brain, and after the infusion of contrast material, intense enhancement was observed. The mass in the left lateral ventricle demonstrated inhomogeneous signal intensity on T1-weighted images, with less intense enhancement, and there was intraventricular hemorrhaging. On T2-weighted images (Fig. 1D), the right lateral ventricular mass demonstrated inhomogeneous low signal intensity and the left lateral ventricular mass also showed low signal intensity. Extraventricular drainage was initiated and dark red blood flowed copiously. Cerebral angiography (Fig. 1E) was performed two days after hemorrhaging. The right lateral ventricular tumor was fed by both the right anterior and right posterior lateral choroidal arteries; the predominant source of vascular supply was the former. The left lateral ventricular tumor showed no vascular abnormality. Surgery revealed that the mass within the right lateral ventricle was hard and yellowish, and adhered to the choroid plexus. Histologic examination demonstrated the presence of psammomatous meningioma in which increased vascularity and intratumoral hemorrhage were at varying stages. The intraventricular hemorrhage was thought to be due to the right lateral ventricular meningioma.

Serial follow-up CT scans showed the complete disappearance of the right ventricular tumor and gradual resolution of the intraventricular hemorrhage, though the left lateral ventricular mass, also identified as a meningioma, remained.

DISCUSSION

Meningioma is the most common intraventricular tumor of the trigone to occur in adults, and intraventricular meningiomas constitute approximately 0.5% to 2% of all intracranial meningiomas. Most meningiomas of the lateral ventricles originate in the trigones of these chambers, extending into their bodies (3-7); they rarly arise in the foramen of Monro (2, 4, 6). As a rule, meningiomas show a female predominance of approximately 2:1. Although they may occur over a wide age range, intraventricular meningiomas are most common over the age of 30 years (3, 6), and the left lateral ventricle is more often affected than the right (6, 8). The origin of intraventricular meningiomas is uncertain, though they appear to arise either from the stroma of the choroid plexus or from arachnoid tissue rests within the choroid, which can explain their frequent occurrence in the trigone. Their CT appearances are similar to those of meningiomas elsewhere. In most cases, they appear as well-defined mass lesions that show marked enhancement after the injection of intravenous contrast material, and calcification is seen in as many as 50% of cases. On T1- and T2-weighted MR images, the lesions are usually isointense to normal brain parenchyma, though their signal intensity may be markedly reduced in the presence of calcification. An obstructing atrial lesion may cause enlargement of the ipsilateral temporal horn (2, 5, 7). Cerebral angiography reveals moderate to marked homogeneous blush, most frequently from the anterior choroidal artery and less commonly from the posterior lateral choroidal artery (5). Meningiomas causing intracranial hemorrhage are infrequent, and hemorrhage from a lateral ventricular meningioma seems to be even rarer (3, 4, 8). To our knowledge, only five cases in which a lateral ventricular meningioma presented with hemorrhage have been described (4), and the patients involved were younger than most with meningioma. Fibroblastic meningioma is the most frequent histologic variation to occur in lateral ventricular meningiomas with hemorrhage. The mechanism of hemorrhage in intraventricular meningioma is still uncertain but may be similar to that occurring in other hemorrhagic neoplasms, in which endothelial obliteration leads to necrosis of the vascular wall and pathologic vascular proliferation results in the formation of thin-walled vessels which rupture easily. The events contributing to hemorrhage of meningiomas may be as follows: 1) the sudden disruption of congested, tortuous vessels which surround the meningioma and are less resistant to blood pressure changes; 2) the rupture of new vessels with thin, softened vascular walls located in the peritumoral zone; 3) bleeding from enlarged and weakened feeding arteries, a phenomenon corresponding to a demand for increased blood supply; and 4) anticoagulation therapy or systemic disorders such as hypertension or atherosclerosis. The intraventricular location of these pathologic vessels presumably favors apoplectic rupture. Hemorrhage from a lateral ventricular meningioma does not usually require decompression such as ventricular drainage or shunt emplacement to relieve obstructive hydrocephalus, suggesting that such hemorrhages may be of venous origin, which is insufficient to obstruct CSF flow. Hemorrhage from a clinically silent meningioma can influence prognosis, and surgery is thus the optimal treatment for this rare disease (4). Differential diagnosis must include metastatic deposits in the choroid plexus which may also cause hemorrhage, though it is unusual for metastases to become so large before presentation. Ventricular hemorrhage is a recognized complication of choroid plexus papillomas, which at imaging may be indistinguishable from meningioma. Choroid plexus tumors are rare after adolescence, and in most cases a patient's age permits clear distinction (2, 3). Primary gliomas may arise in the ventricles, though have not been associated with hemorrhage, and are more commonly found in the body of the ventricle. Ependymomas are much more common in the ventricular body, are rarely calcified, and have not been associated with hemorrhage. Cavernous hemangiomas, neurocytomas and hemangioblastomas are uncommon intraventricular tumors that may present with hemorrhage, and should also be included in the differential diagnosis (3).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download