Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of prophylactic uterine artery embolization (UAE) before obstetrical procedures with high risk for massive bleeding.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective review of 29 female patients who underwent prophylactic UAE from June 2009 to February 2014 was performed. Indications for prophylactic UAE were as follows: dilatation and curettage (D&C) associated with ectopic pregnancy (cesarean scar pregnancy, n = 9; cervical pregnancy, n = 6), termination of pregnancy with abnormal placentation (placenta previa, n = 8), D&C for retained placenta with vascularity (n = 5), and D&C for suspected gestational trophoblastic disease (n = 1). Their medical records were reviewed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of UAE.

Results

All women received successful bilateral prophylactic UAE followed by D&C with preservation of the uterus. In all patients, UAE followed by obstetrical procedure prevented significant vaginal bleeding on gynecologic examination. There was no major complication related to UAE. Vaginal spotting continued for 3 months in three cases. Although oligomenorrhea continued for six months in one patient, normal menstruation resumed in all patients afterwards. During follow-up, four had subsequent successful natural pregnancies. Spontaneous abortion occurred in one of them during the first trimester.

Dilation and curettage (D&C) can cause various complications. Bleeding is one of its most common complications (12). Post-abortion hemorrhage in the second trimester accounts for 33% of cases of abortion-related mortality (3). Bleeding can lead to maternal mortality, especially in high-risk patients with abnormal placentation such as placenta previa and ectopic pregnancy, including cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) (45).

Uterine artery embolization (UAE) is an efficacious treatment approach for postpartum hemorrhage. It has been recently indicated for post-abortion hemorrhage (36). Some reports have suggested that UAE can successfully treat bleeding following D&C in high-risk patients, including those with CSP or abnormal placentation (456). Furthermore, prophylactic UAE has been introduced to decrease intraoperative blood loss in patients at high risk of peripartum hemorrhage (7).

However, few reports are available on the use of prophylactic embolization before obstetric procedures, including therapeutic abortion in high-risk patients with life-threatening vaginal bleeding or expected severe bleeding after an obstetric procedure. The objective of this study was to determine the safety and efficacy of prophylactic UAE in obstetric procedures for preventing hemorrhage in high-risk patients.

This retrospective single-center study was approved by our Institutional Review Board. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to its retrospective nature. This study included 29 female patients who underwent prophylactic UAE between June 2009 and February 2014 before undergoing obstetric procedures, including D&C and delivery for termination of pregnancy and procedures commonly associated with massive bleeding. Characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. Indications for prophylactic UAE were as follows: D&C associated with ectopic pregnancy (CSP, n = 9; cervical pregnancy, n = 6), termination of pregnancy with abnormal placentation (placenta previa, n = 8), D&C for retained placenta with vascularity (n = 5), and D&C for suspected gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD; n = 1). One patient (Patient 4) had symptomatic vaginal bleeding after full-term delivery. She underwent D&C for treatment of retained placenta after prophylactic embolization. A multiparous patient (Patient 10) was diagnosed to have a fetal death with placenta previa at the beginning of the second trimester. Even though she had no symptomatic bleeding, the obstetrician decided to perform prophylactic UAE at the request of the patient due to her painful memory of postpartum bleeding in a previous pregnancy. Symptomatic vaginal bleeding was present in 21 patients before UAE.

The mean age of patients was 33.9 ± 6.0 years. Of these patients, 25 (86.2%) were multiparous and four (13.8%) were nulliparous. The mean gestational age was 12.1 ± 8.2 weeks. During hospital stay, conservative treatments were administered to all patients. Transfusion was performed depending on clinical situation.

After puncturing the common femoral artery, a 5 Fr vascular sheath was inserted. Uterine arteries and other potential bleeding focuses were evaluated by selective bilateral internal iliac arteriogram. A cobra catheter (Radifocus; Terumo Medical Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and 0.035-in guidewire were used to obtain access to the contralateral internal iliac artery. Waldman loop technique was used for selecting the ipsilateral internal iliac artery with the same catheter. A microcatheter (Progreat; Terumo Medical Corp.) was used to select the uterine artery according to a roadmap image. Bilateral UAE at the proximal portion of the uterine artery with gelatin sponge particles was performed after artery selection. After UAE, complete occlusion of the target vessel was confirmed by angiography. Pain control during and after UAE was performed conservatively. UAE was performed in our angiographic suite by interventional radiologists with 5 to 25 years of experience.

Technical success was defined as successful catheterization and embolization of the target culprit arteries that resulted in hemostasis at the final angiography. Clinical success was defined as the termination of bleeding after the initial UAE without needing additional UAE or surgery for hemostasis after D&C. We obtained data on baseline characteristics, treatment before embolization, hemoglobin levels before/after UAE, required transfusions, embolization technique details, and clinical follow-up through careful review of obstetric medical records of patients. We also reviewed their medical records at follow-up visits 1 and 3 months after discharge to obtain data on their menstrual cycles or pregnancies after UAE and subsequent D&C.

The outcomes of the 29 patients are summarized in Table 1. The technical success rate was 100%. Complete embolization of bilateral uterine arteries on pelvic angiography was achieved for all included patients. No bleeding problem occurred. Transfusion or hysterectomy was not required during or after the obstetric procedures. The estimated amount of blood loss during the obstetric procedure was < 500 mL in all patients. No procedure-related complications occurred after UAE. One patient (Patient 6) clinically showed chorioamnionitis after the abortive delivery. Fetal death was suspected. After conservative treatment, the patient fully recovered.

The following obstetric procedures were used: D&C (n = 21), delivery (n = 6), hysterotomy (n = 1), and hysterosalpingoscopic removal of remnant placenta (n = 1). Therapeutic abortion with delivery (n = 6) was performed in cases of fetal death due to known fatal fetal anomaly. Two patients (Patients 3 and 15) underwent hysterotomy or hysterosalpingoscopic removal under general anesthesia. The remaining 27 patients underwent obstetrical procedures under local anesthesia without conscious sedation. The mean interval between UAE and the obstetric procedure was 0.6 ± 1.0 days. The obstetric procedure was performed on the same day as UAE in 18 patients. The mean hospital stay duration after the obstetric procedure was 1.9 ± 2.1 days (range, 1–9 days). The mean hemoglobin levels before and after UAE were 11.3 ± 2.1 and 10.9 ± 1.4 g/dL, respectively. Before the procedure was performed, transfusion of blood product at emergency unit was conducted for two patients (Patients 2 and 23). Both patients had severe anemia with hemoglobin levels of 7.2 and 5.8 g/dL, respectively. After transfusion, UAE and subsequent D&C were performed successfully.

The angiographic findings included diffuse uterine enhancement (n = 27) and mass-like enhancement (n = 2, Patients 1 and 21) (Fig. 1). In three patients (Patients 9, 12, and 20), the bony structure of the fetus was visible due to advanced gestational age. No pseudoaneurysm or active contrast extravasation was found. To increase the possibility of future pregnancy, all women underwent bilateral embolization by using gelatin sponge particles rather than polyvinyl alcohol (Figs. 2, 3). No arteries other than uterine arteries were embolized.

All patients underwent routine follow-up in an outpatient clinic after discharge. Successful hemostasis with minimal post procedural vaginal bleeding was confirmed after UAE. In three cases (Patients 7, 8, and 15), vaginal spotting continued for 3 months. Although oligomenorrhea continued for 6 months in one patient (Patient 10), normal menstruation resumed in all other patients. Four patients (Patients 15, 18, 19, and 21) had successful natural pregnancies during follow-up. Two patients (Patients 18 and 21) had normal cesarean delivery. One patient (Patient 19) had vaginal delivery. One (Patient 15) had a spontaneous abortion during the first trimester.

In the present study, we used prophylactic UAE to manage symptomatic vaginal bleeding or control the high risk of vaginal bleeding during obstetric procedures. We found that patients with high-risk of symptomatic vaginal bleeding who were treated with UAE followed by an obstetric procedure experienced no serious bleeding complication. No severe side effects related to UAE were observed. Our study indicated that prophylactic UAE followed by an obstetric procedure might be an effective treatment for patients at high risk of bleeding. Our results also suggested that UAE followed by an obstetric procedure did not increase the risk of side effects. We assessed four categories as indications for prophylactic UAE. One category (n = 15) comprised ectopic pregnancies such as cervical pregnancy and CSP that could cause serious bleeding after abortion (usually in the first trimester). The second category (n = 8) included abnormal placentation such as placenta previa, accreta, and percreta that could cause serious bleeding. All patients in this category had fetal death or serious fetal anomaly and needed therapeutic abortion. The third category (n = 5) had retained placental tissue that could cause active bleeding after delivery or previous abortion. Before repeating D&C to treat retained tissue that caused active bleeding, prophylactic UAE was performed to prevent massive bleeding during the repeated D&C. The final category (n = 1) was GTD with active bleeding.

Although induced abortion has low morbidity and mortality, hemorrhage is the most common serious complication. Hemorrhage is defined as an estimated blood loss volume of > 500 mL or bleeding requiring a transfusion. It occurs in approximately 0.82 cases per 100000 abortions (68). When initial conservative methods fail, hemorrhage can lead to hysterectomy in approximately 1.1–1.4 cases per 10000 abortions (29). The increasing rate of primary and repeated cesarean deliveries has increased the incidence of abnormal placentation, including CSP, placenta previa, and cervical pregnancy (10). Before performing invasive methods such as laparoscopy, laparotomy, and hysterectomy, UAE is recommended because it is associated with less morbidity and mortality (3). Although UAE is less commonly used for post-abortion hemorrhage, this method has been successful in most published cases (61112). Steinauer et al. (6) have reported that UAE is successful in avoiding hysterectomy in 38 (90%) of 42 patients with post-abortion hemorrhage. In their study, all embolization failures occurred in women who received histopathological confirmation of placenta accreta, increta, or percreta (6). In our study, 8 of the 29 patients had abnormal placentation. However, D&C after UAE resulted in no hysterectomy or massive bleeding, suggesting that prophylactic UAE was successful, even in this group of patients with high risk of bleeding.

Clinical trials of prophylactic UAE before D&C or during delivery to avoid serious complications of post-abortion hemorrhage in patients at high risk for bleeding have been reported (57). Wang et al. (5) have used a prophylactic UAE before D&C in 128 patients with CSP. Among these patients, 113 showed intraoperative blood loss volume of < 500 mL after prophylactic UAE (5). In 10 of 15 patients with intraoperative blood loss volumes of > 500 mL, uterus was preserved, suggesting that prophylactic UAE was at least successful in preventing hysterectomy (5). If the patient still bled > 500 mL, UAE was not successful for preventing bleeding. In our cohort, 15 of 29 patients had CSP or cervical pregnancy. All of them underwent successful prophylactic UAE before D&C. An important advantage of prophylactic UAE is that it prevents blood loss during D&C in high-risk patients, resulting in decreased morbidity. D&C can sometimes result in unforeseen massive bleeding. However, elective prophylactic UAE may decrease the risk of this complication and preserve fertility by avoiding undesired hysterectomy for unsuspected bleeding during therapeutic abortion.

Serious complications, including labial or vaginal necrosis with bladder fistula and endometrial atrophy with permanent amenorrhea, have been reported to be related to UAE in several studies (1314). In our study series, none of our patients had any complications related to prophylactic UAE. The reason for this might be due to the fact that the embolic material we used was biodegradable. It could be more easily absorbed than its alternatives (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol). Gel particles begin to be absorbed gradually at 7–10 days after UAE. Therefore, the uterine arteries might have recovered patency over time. In our study series, all women who underwent prophylactic UAE and obstetric procedures experienced restored menstruation, even though no subsequent pregnancy occurred in many of these patients. Hong et al.(15) have found that all patients (n = 8) have fully recovered menstruation after UAE, similar to the results of our study.

This study had several limitations. One key limitation was that our patients were selected for inclusion at their obstetricians' clinical request, resulting in selection bias. Eight (27.6%) of the 29 patients who did not have vaginal bleeding underwent prophylactic UAE to avoid expected life-threatening bleeding complication based on obstetrician guidance. Prophylactic UAE decreased bleeding risk and obstetricians' concerns about the potential loss of patient's life or her uterus. A prospective randomized study with a control group is required to confirm our results. The small number of patients included as our study sample could also be a limitation, even though our patients had relatively rare indications for UAE. In addition, our follow-up period and the data obtained were insufficient to fully evaluate the influence of UAE on future pregnancies.

In conclusion, prophylactic UAE before an abortive procedure in patients with high risk of bleeding or symptomatic bleeding might be a safe and effective way to manage or prevent serious bleeding, especially for women who wish to preserve their fertility. This procedure can decrease the morbidity, mortality, and the risk of undesired hysterectomy during an obstetric procedure in high-risk patients.

Figures and Tables

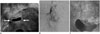

Fig. 1

Placenta previa.

A, B. Angiograms of left (A) and right uterine arteries (B) showing diffuse contrast staining (arrows), suggesting placenta on lower uterine body. Fetus (arrowheads) was confirmed to be dead based on ultrasonography. C. Post-embolization angiogram after contrast injection from right internal iliac artery showing devascularized placenta and contrast stasis (arrows) suggesting complete embolization.

Fig. 2

Cervical pregnancy.

A. Transabdominal ultrasonographic image showing gestational sac (arrows) in uterine cervix. Fetus (arrowhead) can also be seen. B. Late arterial angiogram showing engorged uterine artery and contrast staining at uterine cervix. C. Fluoroscopic image after embolization showing contrast stasis due to embolized gel foam in right uterine artery.

Fig. 3

Cesarean section scar pregnancy.

A. Transvaginal ultrasonographic image showing gestational sac (arrows) in anterior wall of lower uterine body. Patient underwent cesarean section 5 years earlier. B. Angiogram of right internal iliac artery showing engorged uterine artery and contrast staining in lower uterine body. C. Fluoroscopic image after embolization showing contrast stasis due to embolized gel foam in right uterine artery.

Table 1

Patients' Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes (n = 29)

References

1. De Sutter TC, Lohle PN, Boekkooi PF. [Severe blood loss days after suction and curettage: consider a pseudoaneurysm]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2013; 157:A6004.

2. Bartlett LA, Berg CJ, Shulman HB, Zane SB, Green CA, Whitehead S, et al. Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 103:729–737.

3. Kerns J, Steinauer J. Management of postabortion hemorrhage: release date November 2012 SFP Guideline #20131. Contraception. 2013; 87:331–342.

4. Zhuang Y, Huang L. Uterine artery embolization compared with methotrexate for the management of pregnancy implanted within a cesarean scar. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 201:152.e1–152.e3.

5. Wang JH, Qian ZD, Zhuang YL, Du YJ, Zhu LH, Huang LL. Risk factors for intraoperative hemorrhage at evacuation of a cesarean scar pregnancy following uterine artery embolization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013; 123:240–243.

6. Steinauer JE, Diedrich JT, Wilson MW, Darney PD, Vargas JE, Drey EA. Uterine artery embolization in postabortion hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 111:881–889.

7. Izbizky G, Meller C, Grasso M, Velazco A, Peralta O, Otaño L, et al. Feasibility and safety of prophylactic uterine artery catheterization and embolization in the management of placenta accreta. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015; 26:162–169. quiz 170.

8. Le Gall J, Fichez A, Lamblin G, Philip CA, Huissoud C. [Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies: combined modality therapies with uterine artery embolization before surgical procedure]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2015; 43:191–199.

9. Grimes DA, Flock ML, Schulz KF, Cates W Jr. Hysterectomy as treatment for complications of legal abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 1984; 63:457–462.

10. Warshak CR, Eskander R, Hull AD, Scioscia AL, Mattrey RF, Benirschke K, et al. Accuracy of ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 108(3 Pt 1):573–581.

11. Borgatta L, Chen AY, Reid SK, Stubblefield PG, Christensen DD, Rashbaum WK. Pelvic embolization for treatment of hemorrhage related to spontaneous and induced abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 185:530–536.

12. Haddad L, Delli-Bovi L. Uterine artery embolization to treat hemorrhage following second-trimester abortion by dilatation and surgical evacuation. Contraception. 2009; 79:452–455.

13. Godfrey CD, Zbella EA. Uterine necrosis after uterine artery embolization for leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 98(5 Pt 2):950–952.

14. Cottier JP, Fignon A, Tranquart F, Herbreteau D. Uterine necrosis after arterial embolization for postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 100(5 Pt 2):1074–1077.

15. Hong TM, Tseng HS, Lee RC, Wang JH, Chang CY. Uterine artery embolization: an effective treatment for intractable obstetric haemorrhage. Clin Radiol. 2004; 59:96–101.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download