Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) with sodium tetradecyl sulfate (STS) liquid sclerotherapy of gastric varices.

Materials and Methods

Between February 2012 and August 2014, STS liquid sclerotherapy was performed in 17 consecutive patients (male:female = 8:9; mean age 58.6 years, range 44–86 years) with gastric varices. Retrograde venography was performed after occlusion of the gastrorenal shunt using a balloon catheter and embolization of collateral draining veins using coils or gelfoam pledgets, to evaluate the anatomy of the gastric varices. We prepared 2% liquid STS by mixing 3% STS and contrast media in a ratio of 2:1. A 2% STS solution was injected into the gastric varices until minimal filling of the afferent portal vein branch was observed (mean 19.9 mL, range 6–33 mL). Patients were followed up using computed tomography (CT) or endoscopy.

Results

Technical success was achieved in 16 of 17 patients (94.1%). The procedure failed in one patient because the shunt could not be occluded due to the large diameter of gastrorenal shunt. Complete obliteration of gastric varices was observed in 15 of 16 patients (93.8%) with follow-up CT or endoscopy. There was no rebleeding after the procedure. There was no procedure-related mortality.

Bleeding from esophageal and gastric varices is a life-threatening complication of portal hypertensive conditions (1). Bleeding from gastric varices is more fatal and difficult to manage with endoscopy than that from esophageal varices (2). Treatment of gastric varices with gastrorenal shunts was first proposed by Olson et al. (3) in 1984, and Kanagawa et al. (4) developed the balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) procedure in 1996. In Japan, ethanolamine oleate has been used as an endovascular sclerosant in BRTO, but not in other countries due to its potent adverse effects, such as hemolysis, hemoglobinuria, and hemolysis-induced renal failure, and lack of availability of an antidote (5). Outside Japan, 3% sodium tetradecyl sulfate (STS) has been widely used as an alternative sclerosant in BRTO, since its introduction in the United States in 2006 (6). Foam sclerotherapy, proposed by Tessari et al. (7), is commonly accepted as a standard treatment for varicose veins, and is known to be more effective than liquid sclerotherapy, even with less volume (8). Therefore, STS liquid sclerotherapy is now rarely used for the treatment of gastric varices. However, there are several reports on the ability of portopulmonary venous anastomosis (PPVA) to cause systemic paradoxical embolism (910). In addition, one study reported that some complications such as deep vein thrombosis, visual disturbances, headache, migraines, and chest tightness, occur more frequently with foam sclerotherapy than with liquid sclerotherapy (11). For these reasons, we used the STS liquid sclerosant in BRTO.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of BRTO using STS liquid for the treatment of gastric varices.

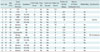

Between February 2012 and August 2014, 17 consecutive patients (8 men and 9 women; mean age 58.6 years, range 44–86 years) with gastric varices underwent BRTO at our hospital. Of 17 patients, 15 were bleeding cases and 2 were prophylactic cases. Liver cirrhosis was caused by hepatitis B virus (n = 3), hepatitis C virus (n = 3), chronic alcohol ingestion (n = 7), cardiac disorder (n = 1), biliary disease (n = 1), autoimmune hepatitis (n = 1), or cryptogenic causes (n = 1). All patients presenting with active bleeding underwent emergent endoscopy for diagnosis and bleeding control. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was performed in all patients, after stabilization of vital signs. All abdominal CT scans showed variable-size gastric varices with a gastrorenal shunt. The demographic characteristics of patients were summarized in Table 1.

Although informed consent was waived for the retrospective study, written informed consent for the BRTO procedure was obtained from all patients or their family. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital.

Venous access was obtained under ultrasound guidance with a 21-gauge micropuncture set. An 8 Fr curved catheter introducer sheath (Ansel, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was inserted through the right common femoral (n = 16) or right internal jugular vein (n = 1) under local anesthesia. The tip of the 8 Fr introducer sheath was advanced to the left renal vein. A 5 Fr Simmons II catheter (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was used to select the gastrorenal shunt. A 0.035-inch stiff guidewire (Radiofocus, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was placed in the gastric varices, and an occlusion balloon (11–20 mm diameter; Clinical Supply, Gifu, Japan) was placed into the gastrorenal shunt. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous venography was performed to evaluate the anatomy of the gastric varices and portosystemic collateral veins and the existence of PPVA. Metallic coils (Nester; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) or gelfoam pledgets, selectively positioned using a microcatheter, were used to occlude the collateral veins, such as the inferior phrenic veins or the pericardiacophrenic veins, whenever the whole gastric-variceal system was not fully opacified. Coils or gelfoam pledgets were used for embolization of collateral draining veins depending on the draining venous diameter. Repeat retrograde venography was performed to confirm if the gastric varices were completely filled with nonionic contrast medium (CM) (iomeprol [Iomeron] 350, Bracco Imaging, Milano, Italy). If retrograde venography showed complete opacification of the gastric varices and stagnation of CM in the gastric varices, we injected a mixture of STS (3% Sotradecol, AngioDynamics, Inc., Queensbury, NY, USA) and nonionic CM using a coaxially inserted microcatheter to reduce the injection volume of STS. The 2% liquid sclerosant was prepared by mixing 3% STS with CM in a 2:1 volume ratio. The amount of instilled sclerosant was determined when the afferent vein was opacified by the radio-opaque sclerosant. The inflated occlusion balloon was left in place for 4–6 hours, before deflation and withdrawn under fluoroscopic guidance. If the procedure began towards the end of the work day, overnight inflation was performed. Technical success was defined as successful occlusion of the gastrorenal shunt, with a balloon catheter, and stagnation of sclerosant in the gastric varices for more than 4 hours without balloon rupture. Obliteration of varices was defined as absence of residual enhancement within the gastric varices on follow-up CT, or disappearance of the gastric varices on endoscopy.

Follow-up data related to the obliteration of gastric varices, rebleeding, and clinical complications were obtained from patient medical records. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT or endoscopy was performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months, and every 6 months thereafter. Follow-up intervals for the patients were determined depending on the individuals' circumstances.

Hepatic and renal function test including total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, serum blood urea nitrogen, and serum creatinine were evaluated 1 day after the procedure. Procedure-related complications were assessed according to criteria from the Society of Interventional Radiology (12). Minor complications were defined as complications requiring nominal or no therapy, whereas major complications were defined as those requiring prolonged hospitalization for therapy or those causing permanent adverse sequelae. The 30-day mortality rates were also noted.

The collected data were analyzed using PASW Statistics 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or number of patients (%). The differences of measured laboratory data associated with hepatic and renal function before and after the BRTO were compared by Mann Whitney U-test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The technical success rate was 94.1% (16/17 patients). One technical failure (patient ID No. 15) was due to the inability to occlude the gastrorenal shunt because of its large diameter (32 mm). Actually, the occlusion balloon catheter could occasionally be placed barely in the orifice of the gastrorenal shunt but slipped out of the position. Ehe attempt to advance the balloon catheter into the periphery of the gastrorenal shunt was unsuccessful. Subsequently, another trial via right internal jugular vein was made but occlusion of gastrorenal shunt could not be achieved. However, gastric variceal bleeding was controlled with terlipressin and this patient was discharged the next day.

Embolization of the collateral veins with coils or gelatin pledgets was performed in 15 patients. The mean volume of liquid sclerosant was 19.9 ± 7.8 mL (range 6–33 mL). Follow-up abdominal CT or endoscopy could not be performed in 2 patients (ID No. 1 and 6) because these patients were lost to follow-up. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT and endoscopy revealed complete obliteration and no recurrence of gastric varices in 15 out of 16 (93.8%) patients during the follow-up period (median 142 days, range 3–673 days) (Fig. 1). One patient (ID No. 17) showed recanalization of gastric varices in the 3 months post-procedure, but rebleeding was not present during the follow-up period.

Two patients experienced complications related to the BRTO procedure, one with left renal vein thrombosis without symptoms (patient ID No. 11) and the other with transient increase of ascites (patient ID No. 5). Retrograde venography showed no PPVA in this study. After the procedure, there were no major complications, such as paradoxical embolism or pulmonary thromboembolism. There was no case of balloon catheter rupture and no deaths within 30 days. The overall results were also summarized in Table 1. There were no significant changes in laboratory data before and after the BRTO. Hepatic and renal function test data were presented in Table 2.

Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration is recognized as an effective treatment for gastric varices (13) and an alternative to transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt according to the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria (6). To date, several types of sclerosing agents, such as ethanolamine oleate, STS, polidocanol, absolute ethanol, and N-butyl-cyanoacrylate, have been used for sclerosis of gastric varices. Among these, STS and polidocanol are the most commonly used sclerosants in countries where ethanolamine oleate is not available. STS and polidocanol are surfactants that are used in a foam or liquid form to disrupt the endothelial lining of blood vessels and inducing endovascular occlusion (14).

Since foam sclerotherapy in the treatment of varicose veins shows greater efficacy and requires smaller treatment doses than liquid sclerotherapy (1516), foam sclerosants have been used in most BRTO procedures. Nonetheless, foam sclerotherapy has been shown to cause serious neurologic complications, including visual disturbance and cerebrovascular attack (111718). One possible mechanism for these effects is that foam microemboli enter the left circulation through the patent foramen ovale (PFO), or another right-to-left shunt, secondary to pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (19). In addition, there have been several reports of PPVA during BRTO (910). PPVA was firstly described by Schoenmackers and Vieten (20) in 1953, and is an unusual collateral channel between the portal and the bronchial venous systems observed in patients with portal hypertension. PPVA is a means of right-to-left shunt, which may result in systemic arterial embolization when foam sclerosants, or particle-like embolic materials, are injected into these collateral channels. Until now, there have been 9 reports of serious cerebrovascular events associated with the treatment of varicose veins using foam sclerotherapy (21), and paradoxical embolization caused by N-butyl-cyanoacrylate during the treatment of gastric varices (2223).

Recently, vascular plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (PARTO) was introduced in some countries where ethanolamine oleate is not available (24). This procedure showed high technical and clinical success rate for the treatment of gastric varices and hepatic encephalopathy. The major advantages of PARTO over BRTO include short procedure time and low procedure-related complications due to unneeded indwelling balloon catheter, sclerosing agent, and selective embolization of efferent veins. However, if selective embolization of efferent veins is not performed in most cases, there is a possibility of migration of gelfoam particles into the systemic circulation via right-to-left shunt such as PPVA, PFO and pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. Therefore, in this study, we used liquid sclerotherapy for the treatment of gastric varices. We also hypothesized that liquid sclerotherapy may be as effective as foam sclerotherapy, because occlusion of the gastrorenal shunt could allow sufficient dwelling time of the sclerosant, and it would be safer than foam sclerotherapy, even if sclerosant leakage into either the portal or the systemic veins occurred. However, there have been no reports of paradoxical embolization during BRTO, possibly due to the stable stagnation of sclerosant within the gastric varices. Nevertheless, given the possibility of right-to-left shunt and PPVA, caution is required when injecting gas containing sclerosants or particle like embolic materials into the gastric varices.

To our knowledge, few studies have been conducted on the efficacy and safety of liquid sclerotherapy in BRTO. Complete obliteration of the gastric varices has been reported in 82–100% of patients (25) and rebleeding rate is reportedly as high as 15% (26). In the present study, complete obliteration of gastric varices was achieved in 93.8% of patients, and rebleeding rate was 6.3%. These results are comparable to those obtained with foam sclerotherapy in the treatment of gastric varices. These results can be attributed to the displacement and dilution of the blood component in the gastric varices by injection of CM during retrograde venography before sclerotherapy, and allowing for sufficient contact time between the veins and the liquid sclerosant due to the stagnation of the sclerosant within the gastric varices. Therefore, it is important to ensure complete stagnation of the sclerosant within the gastric varices in order to achieve adequate results.

According to manufacturer's instructions, the maximum single treatment dose of STS should not exceed 10 mL. In our study, although 11 patients received more than 10 mL STS, no overdose-related adverse events were observed after the procedure. In a study by Sabri et al. (27), the mean total doses of the sclerosing mixture and of 3% STS were 34.1 mL and 10 mL, respectively, which were also without any procedural-related major complications or mortality. This finding can likewise be attributed to the stagnation of sclerosant within the gastric varices.

Our study showed that BRTO using STS liquid sclerotherapy can be a safe and effective treatment option for gastric varices. Hence, stagnation of the sclerosant within the gastric varices may play a major role in preventing systemic adverse effects. Therefore, strict control of STS dosage may be unnecessary, whereas complete filling of the varices with sclerosant may be much more important in BRTO.

The main limitations of this study are its retrospective design and small sample size. Although our study suggests that liquid sclerotherapy could be an option for treating gastric varices, a direct comparison study with larger sample size between liquid and foam sclerotherapy with randomized controlled trial is required.

In conclusion, this study showed that BRTO using STS liquid sclerotherapy can be a clinically safe and effective method for treating gastric fundal varices with gastrorenal shunts in the short term. This modified technique may be safer than BRTO with foam sclerosing agents in some specific cases such as gastric varices. Therefore, the results of our study may be useful in countries where 10% ethanolamine oleate is not available.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

59-year-old woman (patient ID No. 5) presented with hematemesis and melena from gastric varices.

A. Fluoroscopic image shows liquid sclerotherapy with 16-mL mixture of 3% STS and nonionic contrast media (final STS concentration was 2%). To note that no air bubbles are present in gastric varices. B. Contrast-enhanced CT scan obtained before BRTO shows multiple dilated gastric varices (arrows). C. Contrast-enhanced CT scan obtained 98 days after BRTO shows complete resolution of gastric varices (arrows). BRTO = balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration, CT = computed tomography, STS = sodium tetradecyl sulfate

Table 1

Patient Demographic Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes of BRTO

AIH = autoimmune hepatitis, BRTO = balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration, EIS = endoscopic injection sclerosis, F = female, F/L = follow-up loss, H = hematemesis, HBV = hepatitis B virus, HCV = hepatitis C virus, M = male, Me = melena, O = obliteration, R = recanalization, RV = renal vein, TO = thrombotic occlusion

Table 2

Laboratory Data of Hepatic and Renal Function Test before and after BRTO

References

1. Saad WE, Sabri SS. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO): technical results and outcomes. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2011; 28:333–338.

2. Rockey DC. Management of gastric varices. Gastroenterology. 2001; 120:1875–1876. discussion 1876-1877

3. Olson E, Yune HY, Klatte EC. Transrenal-vein reflux ethanol sclerosis of gastroesophageal varices. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984; 143:627–628.

4. Kanagawa H, Mima S, Kouyama H, Gotoh K, Uchida T, Okuda K. Treatment of gastric fundal varices by balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996; 11:51–58.

5. Kiyosue H, Mori H, Matsumoto S, Yamada Y, Hori Y, Okino Y. Transcatheter obliteration of gastric varices: Part 2. Strategy and techniques based on hemodynamic features. Radiographics. 2003; 23:921–937. discussion 937

6. Saad WE, Simon PO Jr, Rose SC. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014; 37:299–315.

7. Tessari L, Cavezzi A, Frullini A. Preliminary experience with a new sclerosing foam in the treatment of varicose veins. Dermatol Surg. 2001; 27:58–60.

8. Hamel-Desnos C, Allaert FA. Liquid versus foam sclerotherapy. Phlebology. 2009; 24:240–246.

9. Miura H, Yamagami T, Tanaka O, Yoshimatsu R. Portopulmonary venous anastomosis detected at balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric varices. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013; 24:131–134.

10. Kariya S, Komemushi A, Nakatani M, Yoshida R, Kono Y, Shiraishi T, et al. Portopulmonary venous anastomosis in balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for the treatment of gastric varices. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 29:1522–1527.

11. Guex JJ. Complications and side-effects of foam sclerotherapy. Phlebology. 2009; 24:270–274.

12. Sacks D, McClenny TE, Cardella JF, Lewis CA. Society of interventional radiology clinical practice guidelines. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003; 14(9 Pt 2):S199–S202.

13. Kitamoto M, Imamura M, Kamada K, Aikata H, Kawakami Y, Matsumoto A, et al. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric fundal varices with hemorrhage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 178:1167–1174.

14. Cameron E, Chen T, Connor DE, Behnia M, Parsi K. Sclerosant foam structure and stability is strongly influenced by liquid air fraction. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013; 46:488–494.

15. Saad WE, Nicholson D, Lippert A, Wagner CC, Turba CU, Sabri SS, et al. Balloon-occlusion catheter rupture during balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices utilizing sodium tetradecyl sulfate: incidence and consequences. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2012; 46:664–670.

16. Alòs J, Carreño P, López JA, Estadella B, Serra-Prat M, Marinel-Lo J. Efficacy and safety of sclerotherapy using polidocanol foam: a controlled clinical trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006; 31:101–107.

17. Gillet JL, Guedes JM, Guex JJ, Hamel-Desnos C, Schadeck M, Lauseker M, et al. Side-effects and complications of foam sclerotherapy of the great and small saphenous veins: a controlled multicentre prospective study including 1,025 patients. Phlebology. 2009; 24:131–138.

18. Forlee MV, Grouden M, Moore DJ, Shanik G. Stroke after varicose vein foam injection sclerotherapy. J Vasc Surg. 2006; 43:162–164.

19. Ceulen RP, Sommer A, Vernooy K. Microembolism during foam sclerotherapy of varicose veins. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358:1525–1526.

20. Schoenmackers J, Vieten H. [Portocaval and portopulmonary anastomoses in postmortem portography]. Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr. 1953; 79:488–498.

21. Asbjornsen CB, Rogers CD, Russell BL. Middle cerebral air embolism after foam sclerotherapy. Phlebology. 2012; 27:430–433.

22. Tan YM, Goh KL, Kamarulzaman A, Tan PS, Ranjeev P, Salem O, et al. Multiple systemic embolisms with septicemia after gastric variceal obliteration with cyanoacrylate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002; 55:276–278.

23. Saracco G, Giordanino C, Roberto N, Ezio D, Luca T, Caronna S, et al. Fatal multiple systemic embolisms after injection of cyanoacrylate in bleeding gastric varices of a patient who was noncirrhotic but with idiopathic portal hypertension. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 65:345–347.

24. Gwon DI, Kim YH, Ko GY, Kim JW, Ko HK, Kim JH, et al. Vascular plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration for the treatment of gastric varices and hepatic encephalopathy: a prospective multicenter study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015; 26:1589–1595.

25. Patel A, Fischman AM, Saad WE. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012; 199:721–729.

26. Hong CH, Kim HJ, Park JH, Park DI, Cho YK, Sohn CI, et al. Treatment of patients with gastric variceal hemorrhage: endoscopic N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection versus balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009; 24:372–378.

27. Sabri SS, Swee W, Turba UC, Saad WE, Park AW, Al-Osaimi AM, et al. Bleeding gastric varices obliteration with balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration using sodium tetradecyl sulfate foam. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011; 22:309–316. quiz 316

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download