Abstract

We present a rare case of a pleural loose body, thought to be a pedunculated pleural tumor, found incidentally in a 58-year-old female. Computed tomography showed a non-enhancing mass, which migrated along the mediastinum and paravertebral area. Thoracoscopic surgery revealed a 4 cm, soap-like mass that was found to be a fibrin body consisting of hyalinized collagen histopathologically. Mobility and the lack of contrast enhancement of a pleural mass are important clues to diagnosing this benign condition.

A pleural loose body, which is also known as a 'pleural mouse', 'pleural fibrin body', or 'thoracolithiasis', is a rare benign condition. There have been several case reports of this benign condition, in which most of the loose bodies were calcified and up to 1.5 cm in size (123). We report a pleural loose body found incidentally that was unusually large and non-calcified, mimicking a pedunculated pleural tumor on imaging studies. This case report was approved by our Institutional Review Board and the patient's informed consent was waived.

A 58-year-old woman presented with a mass found incidentally on a chest radiograph. She had been treated for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia for the past 10 years.

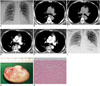

Laboratory tests revealed no abnormality. The posteroanterior chest radiograph showed a well-defined mass with a smooth margin in the right paratracheal area (Fig. 1A). Precontrast computed tomography (CT) showed a 4 cm mass in the subcarinal area (Fig. 1B, C), but on the postcontrast CT obtained 2 minutes later, the mass was observed in the right paravertebral area (Fig. 1D, E). The attenuation value of the mass was 42-44 Hounsfield units on precontrast CT, and the mass did not show contrast enhancement. In a follow-up posteroanterior chest radiograph, the mass had migrated to the subcarinal area (Fig. 1F). The impression based on the imaging studies was a pedunculated solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura, and the differential diagnosis included a benign neurogenic tumor. Cystic mass types, such as the bronchogenic cyst, were not included in the differential diagnosis due to the mass' mobile nature.

The patient underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. A 3 × 4 cm "soap-like" white hard mass was found floating freely in the pleural cavity. The mass did not have a stalk connecting it to the parietal pleura (Fig. 1G). Histopathologically, the mass consisted of hypocellular hyalinized collagen and the surface of the tumor showed some scattered chronic inflammatory cells and the characteristic "basket-weave" configuration of laminated hypocellular mature collagen (Fig. 1H). The final diagnosis was a fibrin body in the pleural cavity.

A pleural loose body is a rare benign condition. There have been a few case reports and case series, mainly from Japan, which variably describe this condition as an 'intrapleural loose body', 'pleural fibrin body', or 'thoracolithiasis' (123456). The pleural loose body is rarely symptomatic and there are no age or sex predilections. Most of the cases were found incidentally on imaging studies or at autopsy, although there have been a few case reports in which the mass developed after a thoracotomy or traumatic pneumothorax (56). The size usually ranges from 5-15 mm (123) and it may or may not be calcified. The largest reported example was a 5 cm calcified mass (7). In our case, the loose body was a 4 cm non-calcified fibrin body, which is the largest reported non-calcified loose body. Although this mass was found around the carina, they tend to be located in the dependent portion of the thorax around the diaphragm.

The mobile nature on sequential imaging studies is the most characteristic finding of a pleural loose body. Kinoshita et al. (3) demonstrated the continuous migration of 11 calcified loose bodies on multiple sequential CTs. Our case also showed spontaneous shifting in every sequential imaging study, even in the 2 minute interval between the pre- and postcontrast CTs. In a retrospective review of our case, another important diagnostic clue differentiating it from soft tissue tumors was the absence of contrast enhancement, although some benign tumors, such as benign neurogenic tumors, can show little contrast enhancement.

The histology of loose bodies has been described. They consist of an outer wall of fibrous tissue and a variable central core which is usually fatty tissue with or without necrosis (8). Calcification may or may not be present. In our case, the entire mass consisted of hyalinized collagen without a fatty core. In cases with a fatty core, magnetic resonance imaging can help with the differential diagnosis, since the fatty core shows high signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images (9).

The etiology remains unclear. Based on the histological features, Kinoshita et al. (3) proposed epipericardial fat necrosis as a possible mechanism for loose bodies with a fatty core, in which twisted, torn epipericardial fat undergoes aseptic fat necrosis and then may drop into the intrapleural space, resulting in a mobile loose body. For loose bodies not containing a fatty core, such as in our case, another possible mechanism is needed. Since loose bodies have occurred after a thoracotomy (5) or traumatic pneumothorax (6) in which an exudative pleural effusion or hemothorax occurs, we postulated that a fibrin clot might form during resolution of the effusion or hemothorax. Although our patient did not have a history of chest-related problems, she might have once suffered from self-limited pleurisy because tuberculous pleurisy is endemic in our country.

A small calcified nodule migrating freely in the pleural cavity is virtually pathognomonic for thoracolithiasis, although a loose body with no or little calcification might be misdiagnosed as a benign neoplasm and resected with unnecessary surgery. Some loose bodies have been reported to grow at follow-up (710). Our case was also misdiagnosed pre-surgically as a benign pedunculated solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura because of its non-calcified nature, mobility, and location between the lung and pleura, although the absence of contrast enhancement on CT did not favor a neoplastic condition. Pre- and postcontrast CT may play an important role in the differential diagnosis and prevention of unnecessary surgery.

In a mass abutting the pleura or mediastinum, the combination of mobility and no contrast enhancement is an important clue to diagnosing a pleural loose body. In patients with these imaging findings, radiologists should recommend clinical observation or minimal surgery for this benign condition.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

58-year-old woman with pleural fibrin body.

A. Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows right paratracheal mass (arrow). B, C. Pre-contrast CT demonstrates soft-tissue density mass in subcarinal area (arrows). Attenuation of mass was 42-44 Hounsfield units (HU). D, E. On postcontrast CT, mass is observed in right paravertebral area (arrows). Mass did not show contrast enhancement and had attenuation value around 44 HU. F. On preoperative chest radiograph obtained 1 month after initial radiograph, no mass is observed in right paratracheal area. Increased opacity in subcarinal area suggests migration of previous right paratracheal mass to subcarinal area. G. Gross tumor specimen is whitish "soap-like" mass with smooth surface. H. In high-power view, surface of tumor shows scattered chronic inflammatory cells and characteristic "basket-weave" configuration of laminated, hypocellular mature collagen (hematoxylin-eosin stain, × 200 magnification).

References

1. Bolca C, Trahan S, Frechette E. Intrapleural thoracolithiasis: a rare intrathoracic pearl-like lesion. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011; 59:445–446.

2. Peungjesada S, Gupta P, Mottershaw AM. Thoracolithiasis: a case report. Clin Imaging. 2012; 36:228–230.

3. Kinoshita F, Saida Y, Okajima Y, Honda S, Sato T, Hayashibe A, et al. Thoracolithiasis: 11 cases with a calcified intrapleural loose body. J Thorac Imaging. 2010; 25:64–67.

4. Spitz WU, Taff ML. Intrapleural golf ball size loose body. An incidental finding at autopsy. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1985; 6:329–331.

5. Kawanami T. [Post-thoracotomy "fibrin body": 16 year follow-up of a case (author's transl)]. Rinsho Hoshasen. 1980; 25:863–866.

6. Euphrat EJ, Beck E. Fibrin body following traumatic pneumothorax; a problem in differential diagnosis of a nodular pulmonary density. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1955; 74:86–89.

7. Dias AR, Zerbini EJ, Curi N. Pleural stone. A case report. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1968; 56:120–122.

8. Iwasaki T, Nakagawa K, Katsura H, Ohse N, Nagano T, Kawahara K. Surgically removed thoracolithiasis: report of two cases. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006; 12:279–282.

9. Tanaka D, Niwatsukino H, Fujiyoshi F, Nakajo M. Thoracolithiasis--a mobile calcified nodule in the intrathoracic space: radiographic, CT, and MRI findings. Radiat Med. 2002; 20:131–133.

10. Kosaka S, Kondo N, Sakaguchi H, Kitano T, Harada T, Nakayama K. Thoracolithiasis. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000; 48:318–321.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download