INTRODUCTION

Median arcuate ligament syndrome (also referred to as celiac artery compression syndrome) is often diagnosed when idiopathic, episodic abdominal pain is associated with dynamic compression of the proximal celiac artery by fibers of the median arcuate ligament. The character of the abdominal pain is often postprandial and associated with regurgitation of undigested food, and weight loss, all of which are caused by gastric ischemia from impingement of the celiac axis (1, 2, 3). But our patient showed that median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) might be a cause of recurrent abdominal pain associated with gastric ulcer and iron deficiency anemia that this association is relatively uncommon and therefore not well determined. In addition, we reported both the computed tomography (CT) angiography findings and three-dimensional reconstructions of this rare case.

CASE REPORT

A 72-year-old male patient was admitted with a five-month history of severe, recurrent postprandial, periumbilical pain associated with alternating bowel function and fatigue and weakness. The pain lasted 30 minutes to hours, and fear of eating led to a 5 kg weight loss. No nausea or vomiting was reported. He denied extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. He had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypertension for twenty years. The physical examination was unremarkable, except for nonspecific epigastric tenderness.

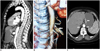

Laboratory evaluation revealed low hemoglobin level (6.2 mg/dL) and mild elevated liver enzymes, low iron 15 µg/dL (37-145), high total iron binding capacity 464 µg/dL (112-346), normal ferritin levels 12.3 ng/mL (4.6-204) and inflammatory markers; erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 45 mm/h while C-reactive protein 46 mg/L. In addition; the patient had normal formed stools per day and fecal occult blood was absent. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed an ulcero-vegetating fragile mass in stomach and biopsies were taken from the lesion. The pathology report diagnosed benign gastric ulcer. The colonoscopy levels were within normal limits. He was, therefore, referred to abdominal ultrasound (US)-Doppler and CT angiography. A US-Doppler of the abdominal vessels showed stenosis of the celiac trunk with an increase in flow velocity during expiration (490 cm/s) and improvement on inspiration. This was confirmed by sagittal CT angiography showing compression of the celiac artery by the median arcuate ligament and post-stenotic dilatation of the celiac artery (Fig. 1A). Three-dimensional reconstructions of CT angiography revealed a severe stenosis and poststenotic dilataion of the proximal celiac artery compatible with celiac artery compression syndrome (Fig. 1B). Axial CT image shows median arcuate ligaments and gastric mucasal thickening with contrast enhacement (Fig. 1C).

Consequently, the patient was surgically treated, releasing the vascular compression. After the operation, he reported a complete relief from postprandial pain which was one of his major concerns. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 4, and was completely symptom-free at two-six-week and six months follow-up visits.

DISCUSSION

In 10% to 24% of the population, the ligament may cross over the proximal portion of the celiac axis, and cause a characteristic indentation (4, 5). In some individuals, the topographic relationships of the neighboring structures are so close that the celiac artery is compressed from above by the ligament. A small subset of this population may present with MALS, an anatomic and clinical entity in which extrinsic compression of the celiac axis leads to postprandial epigastric pain, nausea or vomiting, and weight loss (often related to "food fear" or fear of pain triggered by eating), and some of them had epigastric fullness and bowel function disorders (4, 6).

These symptoms are usually nonspecific and are easily misdiagnosed as functional dyspepsia, peptic ulcer disease, or gastropathy (1, 2, 3). But our patient showed that MALS might be a cause of recurrent abdominal pain associated with gastric ulcer and profound iron deficiency anemia that this association is relatively uncommon and therefore not well determined. As a possible cause of idiopathic reversible gastroparesis and gastric dysrhythmias, theories invoking either a neurogenic or vascular origin for the clinical features associated with MALS have been proposed, but lacks objective evidence to support these theories. The regularization of the gastric electrical rhythm in a previous report after surgical decompression of the celiac axis would support a neurogenic basis for the symptoms associated with MALS (7). However, a few cases of a patient of MALS having both iron deficiency anemia and celiac disease or drug resistant gastric ulcer have been reported (8, 9). Our patient had iron deficiency anemia with gastric ulcer. Proton pump inhibitor and oral iron supplementation therapies were ordered after surgery and the patient was completely symptom free at the follow-up visit.

The syndrome most commonly affects individuals between 20 and 40 years old, and is more common in women, particularly thin women (4). However; our patient was 72 years old male. The diagnosis of MALS is mainly based on the exclusion of other intestinal disorders but once suspected, imaging techniques including Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and selective catheter angiography can be used to identify the abnormality (10).

A reasonable screening test for the suspected patients is duplex ultrasonography that measure the rate of blood flow, enabling quantitative evaluation of celiac artery flow on inspiration and expiration, and comparison of flow rate before, during and after surgery (11). Diagnosis of MALS was made if a greater than 2-fold acceleration of peak systolic flow in the celiac artery compared to the abdominal aorta or a peak systolic velocity greater than 200 cm/s was measured in the mid position and if a variation of flow velocity occurred during respiration (12). However, in our patient; Doppler US of the abdominal vessels showed stenosis of the celiac trunk with an increase in flow velocity on expiration (490 cm/s) and improvement on inspiration.

The CT findings characteristic of MALS may not be appreciated on axial images alone. Sagittal plane in CT angiography is optimal for evaluating the focal narrowing of celiac axis. The focal narrowing of the proximal celiac artery with poststenotic dilatation, indentation on the superior aspect of the celiac artery, and a hook-shaped contour of the celiac artery support a diagnosis of MALS. The hook-shaped contour of the celiac artery is characteristic of the anatomy in MALS and helps distinguish it from other causes of celiac artery stenosis such as atherosclerosis (4, 5). But, in our case, hook shaped appearance was masked due to post-stenotic aneurysmal dilatation.

Additional diagnostic techniques that may be used to aid in the diagnosis of MALS include magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and direct catheter angiography. A definite diagnosis of MALS can be achieved by lateral aortography of the visceral aorta and its branches during inspiration and expiration (13). Lateral aortic angiography is the gold standard but there are other less invasive techniques such as US-Doppler, CT or MRA. In every case it is important to correlate abdominal symptoms with radiological data (14, 15).

Radiologically, the lateral aortogram shows a characteristic superior indentation on the celiac artery about 5 mm from its origin. The presence of poststenotic dilatation and hypertrophy of the pancreaticoduodenal arcades (which act as collateral vessels from the celiac artery) imply a more severe degree of stenosis and hemodynamic significance. Celiac artery compression decreases with inspiration as the abdominal viscera descend, causing the caudal orientation of the celiac artery. It increases with expiration, and in the worst cases the celiac artery occludes (16).

Treatment of MALS is aimed at restoring normal blood flow in the celiac axis and eliminating neural irritation produced by the celiac ganglion fibers. Decompression of the celiac artery is the general approach to treat MALS. The general method of treatment involves an open surgical approach, the mainstay being open division, or separation, of the median arcuate ligament combined with removal of the celiac ganglia. The majority of patients benefit from surgical intervention. A laparoscopic approach may also be used to achieve celiac artery decompression. Endovascular methods such as percutaneous transluminal angioplasty have been used in patients who have failed open and/or laparoscopic intervention (6, 13, 14).

As a result, this case demonstrates that the MALS could be the major cause of recurrent abdominal pain associated with profound iron deficiency anemia, even in existence of other abdominal disorders. For this reason, in patients with upper gastrointestinal disorders, especially postprandial pain, that persist after medical therapy, it could be useful to perform vascular investigation evaluating the possibility of celiac trunk compression.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download