Abstract

Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis (PAM) is a rare chronic disease with paucity of symptoms in contrast to the imaging findings. We present a case of a 24-year-old Malay man having an incidental abnormal pre-employment chest radiograph of dense micronodular opacities giving the classical "sandstorm" appearance. High-resolution computed tomography of the lungs showed microcalcifications with subpleural cystic changes. Open lung biopsy showed calcospherites within the alveolar spaces. The radiological and histopathological findings were characteristic of PAM.

Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis (PAM) is a rare chronic disease characterised by calcifications within the alveoli (calcospherites) and a paucity of symptoms in contrast to the imaging findings. Patients are usually symptom-free until middle age when chronic respiratory failure starts to develop. The radiological and histopathological findings of this young patient were characteristic of PAM. The diagnosis of PAM is incidental in the early age as in this present case. The pathogenesis of PAM has yet to be elucidated (1).

A 24-year-old Malay male patient was referred to the respiratory clinic because of an abnormal pre-employment chest radiograph. He had been smoking about 10 cigarettes a day since he was 21 years of age. He stopped smoking 10 months ago after he noticed he had being having reduced effort tolerance for the past three years. He was an office worker and did not have a history of exposure to organic or inorganic dusts. His two siblings were asymptomatic.

On examination, the patient was not tachypnoeic. There were no signs of finger clubbing or pulmonary hypertension. His oxygen saturation on room air at rest was 94% and dropped to 92% after climbing up four flights of stairs. Spirometry testing revealed a restrictive pattern of lung disease with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and a forced vital capacity (FVC) of 2.7 L (69% of predicted) and 3.2 L (68% of predicted), respectively. The FEV1/FVC ratio was 85%.

His haemoglobin (168 g/L), serum parathyroid hormone (2.9 pmol/L [normal, 1.1-7.3]) and calcium (2.34 mmol/L) levels were normal. 24-hour urine calcium was also normal 6.9 mmol with a 24-hour urine volume of 2.8 L.

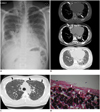

His chest radiograph (Fig. 1A) revealed dense micronodular opacities distributed symmetrically and predominantly in the middle to lower zones of both lungs giving the classical "sandstorm" appearance. The cardiac borders were obscured by the sand-like opacities.

A high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan of the lungs (Fig. 1B) showed widespread tiny microcalcifications throughout the lungs with a preponderance of microliths in the lower lobes. There were associated areas of interlobular septal thickening and ground-glass changes. Subpleural cystic changes were also seen in both lower lobes giving rise to the 'black pleura sign' (Fig. 1C) (2). No pneumothorax or pleural effusion was present. Both the bronchial system (including the small bronchioles) and the size of the pulmonary vessels were normal.

As this was diffuse parenchymal lung disease, videoassisted thoracic surgical (VATS) lung biopsy was planned but the procedure was converted into a mini-thoracotomy because there was difficulty in manoeuvering the endostapler. There was a moderate pneumothorax postmini-thoracotomy from which the patient fully recovered after 5 days in the ward. The lung biopsy specimen revealed features consistent with PAM, with numerous calcospherites within the alveolar spaces (Fig. 1D). The intervening alveolar septae were congested and showed mild fibrosis with infiltrates of mainly lymphoplasmacytic cells.

Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis is characterised by the presence of numerous tiny calculi (calcospherites) within the alveolar spaces, and occurs worldwide with most of the cases coming from Europe (42.7%) and Asia (40.6%) (3). The peak incidence in Japan occurs between the ages of four to nine years, while in the West, the majority of reported cases have been in patients between the ages of 30 to 50 years. There is no gender predilection for this disease. In our case, this young Malay male was less than 30 years old. This early detection was an incidental finding in a pre-employment chest radiograph.

The aetiology and pathogenesis of PAM are unknown. It is widely accepted that the disease has autosomal recessive inheritance (4). Familial occurrence has been noted in more than half of the reported cases. Hypothetical mechanisms that have been proposed include an inborn error of metabolism, an unusual response to an unspecified pulmonary insult, an immune reaction to various irritants, and an acquired abnormality of calcium or phosphorus metabolism. Recently, there have been reports of mutation in type IIb sodium-phosphate cotransporter gene (SCL34A2 gene) in the disease pathogenesis (5).

Plain chest radiographs typically show bilateral areas of micronodular calcifications producing a "sandstorm" appearance that predominates in the middle and lower lung areas as in our patient. The lung bases appear to have increased density due to the greater thickness of the lung tissue there, as well as increased surface densities. This distribution of calcified nodules may be due to the relatively richer blood supply to this area (6). Small apical bullae may be seen with an associated pneumothorax.

High-resolution computed tomography of the thorax shows alveolar calcification that is a mixture of calcified micronodules in a ground glass pattern or consolidation accentuated along the pleural margins and fissures adjacent to the interlobular septa giving rise to polygonous structures and bronchovascular bundles, explaining the coarsely linear nodulations, reticulations and septal lines seen on the HRCT of this patient. The predominance of calcification in the medial rather than the lateral portions of the lung as described by Hoshino et al. (7) was evident in this patient. Some authors consider the interlobular septa of calcium density due to deposition of calcospherites within the peripheral lobular parenchyma as pathognomonic of PAM on the HRCT scan (4). Calcospherites measuring less than 1 mm produce a ground-glass appearance, and with appropriate windowing, such as a bone window, can often be discerned as discrete calcifications (8). It has been postulated by Hoshino et al. that the black pleural line on HRCT is caused not by subpleural cysts but by a fat-dense layer between the ribs and the calcified lung parenchyma. However, a review of the CT and pathologic findings in 10 patients with PAM revealed that the sub-pleural cysts on CT were histologically dilated alveolar ducts (9). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in their patients with PAM showed diffusely increased signal intensity on T1-weighting at the lower lung zones (7). MRI was not performed in our patient as an HRCT was considered sufficient for diagnosing this patient. This patient's HRCT had features characteristic of PAM, which are calcified nodules, calcifications along the interlobular septa and pleura, ground-glass opacities, consolidation, and subpleural cysts. These HRCT features are better demonstrated with 0.75 mm slice thicknesses than with 10 mm thicknesses, which were used prior to 2005 (9).

Chest radiograph and CT scan findings are characteristic, and along with the clinical dissociation (as well as the blood results), are sufficient for diagnosis of the disease, even if microscopic evidence of calcospherites in the alveoli is obtained, as in this patient (3). Lung biopsy for diffuse lung disease such as this is best approached by VATS or open thoracotomy as CT guided lung biopsy is associated with a high risk of complications such as pneumothorax and bronchopleural fistula. Bronchoalveolar lavage has also been used to recover calcospherites which are seen as rounded concentrically laminated masses histopathologically.

Pulmonary function tests are often normal or near normal even with extensive radiograph changes. Progression of the restrictive lung disease is generally very slow. Some patients are followed up for more than 30 years without evidence of significant deterioration (10). End-stage lung disease was reported to occur more frequently among cigarette smoking PAM patients. The florid appearance of PAM on chest radiograph and HRCT in this patient may be attributed to the smoking history. Home-based oxygen therapy is often necessary with advanced disease. Systemic steroids and bronchoalveolar lavage have not been proven to be effective (11). The only definitive treatment for PAM is lung transplant.

Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis is a disease with characteristic radiological and pathological features, and it is asymptomatic till it progresses to restrictive lung disease. As it is uncommon, the radiologist needs to keep this disease in mind if conditions that produce a similar appearance such as occupational lung disease have been excluded.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis.

A. Frontal chest radiograph showing classic sandstorm-like appearance of pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis with symmetrical pattern of diffuse fine micronodules in both lungs and partial obscuration of heart border (arrows). B. Axial HRCT image of lower chest in bone window (top most) and mediastinal window (middle) showing diffuse pattern of microlithiasis, consisting of both discrete nodules and calcified interlobular septae (arrows); and in lung window (bottom most) showing areas of ground-glass attenuation in lung parenchyma (*). C. Axial HRCT image of lung at level of aortic arch in lung window showing subpleural cystic changes (arrows). D. Photomicrograph of section of resected lung tissue showing numerous laminated calcospherites (arrows) within alveolar spaces.

|

References

1. Wallis C, Whitehead B, Malone M, Dinwiddie R. Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis in childhood: diagnosis by transbronchial biopsy. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1996; 21:62–64.

2. Siddiqui NA, Fuhrman CR. Best cases from the AFIP: Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis. Radiographics. 2011; 31:585–590.

3. Mariotta S, Ricci A, Papale M, De Clementi F, Sposato B, Guidi L, et al. Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis: report on 576 cases published in the literature. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2004; 21:173–181.

4. Marchiori E, Gonçalves CM, Escuissato DL, Teixeira KI, Rodrigues R, Barreto MM, et al. Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis: high-resolution computed tomography findings in 10 patients. J Bras Pneumol. 2007; 33:552–557.

5. Corut A, Senyigit A, Ugur SA, Altin S, Ozcelik U, Calisir H, et al. Mutations in SLC34A2 cause pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis and are possibly associated with testicular microlithiasis. Am J Hum Genet. 2006; 79:650–656.

6. Barbolini G, Rossi G, Bisetti A. Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:69–70.

7. Hoshino H, Koba H, Inomata S, Kurokawa K, Morita Y, Yoshida K, et al. Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis: high-resolution CT and MR findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998; 22:245–248.

8. Deniz O, Ors F, Tozkoparan E, Ozcan A, Gumus S, Bozlar U, et al. High resolution computed tomographic features of pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis. Eur J Radiol. 2005; 55:452–460.

9. Sumikawa H, Johkoh T, Tomiyama N, Hamada S, Koyama M, Tsubamoto M, et al. Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis: CT and pathologic findings in 10 patients. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2005; 63:59–64.

10. Mascie-Taylor BH, Wardman AG, Madden CA, Page RL. A case of alveolar microlithiasis: observation over 22 years and recovery of material by lavage. Thorax. 1985; 40:952–953.

11. Tachibana T, Hagiwara K, Johkoh T. Pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis: review and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009; 15:486–490.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download