Abstract

A perivascular epithelioid cell (PEC) tumor is a rare mesenchymal tumor characterized by abundant cytoplasmic Periodic acid-Schiff positive glycogen (also called sugar tumor or clear cell tumor of the lung for this characteristic) and is mostly benign. We report a case of a 63-year-old man who presented with an enlarging mass on chest radiograph. After a thorough workup, diagnosis of malignant pulmonary PEC tumor with lung to lung metastases was established. Herein, the difficulties of diagnosis and management we confronted are described.

A perivascular epithelioid cell (PEC) tumor is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm characterized by abundant cytoplasmic Periodic acid-Schiff positive glycogen. Tumors of this entity are also called a sugar tumor or clear cell tumor for this characteristic.

Although it was originally described in lung by Liebow and Castleman (1), the term 'PEC tumor' is now used as an umbrella term for the family of tumors with PEC (2). Angiomyolipoma, lymphangioleiomyomatosis and clear cell myomelanocytic tumors of the falciform ligament/ligamentum teres are also related members of this family sharing this distinctive cell type. PEC tumors are a group of ubiquitous neoplasms sharing morphological, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural and genetic distinctive features (3). Approximately 50 cases of PEC tumors of the lung are reported (4) and about 100 PEC tumors-not otherwise specified have also been reported (5) in multiple anatomic sites such as the uterus, the genitourinary tract and the gastrointestinal tract.

Patients with pulmonary PEC tumors usually range in age from 40 to 60 years and are equal in prevalence among both genders. Most PEC tumors are benign and present mostly as a peripheral, well-defined, enhancing, and round nodule without cavitation or calcification (4). Intense post-contrast enhancement is one of the characteristics of the PEC tumor and this appears to be related to rich vascular stroma (6). They manifest as an incidental solitary pulmonary nodule in asymptomatic patients (except for few cases with symptoms of hemoptysis).

Malignant PEC tumors arising from the lung are very rare and only four cases have been reported so far in the English-language literature (4, 7-9) and little is known about their radiologic findings. In the present report, we describe a case of a malignant pulmonary PEC tumor with lung to lung metastases and discuss the difficulties of diagnosis and management we confronted with a literature review.

A 63-year-old male nonsmoker with chest radiograph's abnormality was referred to our hospital. He was asymptomatic and denied any weight loss, cough, wheezing or hemoptysis. Physical examination and laboratory results were unremarkable.

The chest radiograph showed a large mass in the left lower lung zone, abutting the mediastinal structures (Fig. 1A-F). On computed tomography, a 9 × 12-cm-sized, well-circumscribed, and solid mass was located in the posteromedial aspect of the left lower lobe with wide pleural attachment. There was no displacement of bronchovascular bundles in adjacent lung parenchyma and bone remodeling. Close observation disclosed air-bronchograms in the peripheral portion of the tumor. For these reasons, this tumor seemed to be originated from the lung parenchyma rather than the posterior mediastinum or pleura. The mass contained curvilinear calcifications and showed heterogeneous enhancement (solid portion showed strong contrast enhancement; 37 HU on pre-contrast image and 115 HU on post-contrast image) with contrast-medium injection. On the lung window image, several discrete subcentimeter nodules were also noted in both lungs, raising the possibility of lung-to-lung metastases. There was no significant mediastinal or hilar lymph node enlargement. Our final radiological differential diagnosis included lung cancer or malignant sarcoma of the lung. 18F-FDG PET CT depicted a hypermetabolic mass with SUVmax of 4.4 in the left lower lobe and several small nodules with faint uptake.

The patient underwent left lower lobectomy. Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery resection was planned initially but was converted to an open thoracotomy due to severe adhesion and large mass size. On the surgical field, the tumor appeared to be a lung parenchymal lesion, probably originating from the lung parenchyma near to the left lower lobar bronchus. On gross pathologic examination, the tumor appeared as a yellow-tan, well-demarcated mass with internal hemorrhage. The left lower lobar bronchus and the visceral pleura were involved with the tumor.

Microscopic examination showed sheets of round to polygonal cells with little clustering. The tumor cells had abundant clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm with oval nuclei (Fig. 1G). Histopathologic differentiation included clear cell pulmonary carcinoma, metastasis from renal cell carcinoma, malignant form of paraganglioma, and PEC tumor. The tumor cells were immunoreactive for SMA, S-100 and CD56, but were nonreactive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, HMB45, CD10, CD34, chromogranin and synaptophysin. According to these results, other histopathologic differential diagnoses other than the PEC tumor were excluded. Thus, the histopathologic diagnosis was reported as the clear cell (sugar) tumor of the lung (i.e., PEC tumor), low grade malignancy. The Ki-67 score was 10% and there was no vascular, lymphatic or perineural invasion. Tumor resection margin was negative for malignancy. At ultrastructural analysis using electron microscopy (not shown), PECs contained microfibrillar bundles with electron-dense condensation.

A follow up CT obtained 4 months after the operation revealed enlarged metastatic nodules in both lungs. Compared with the pre-operation CT, the lesion in RLL increased in diameter from 3.8 mm to 7.3 mm within 6 months and then to 9.4 mm within another 6 months. Multifocal wedge resection for the several nodules was performed after 1 year from the initial operation and led to the diagnosis of metastatic lesions from the PEC tumor. However, there are still remaining metastatic lesions, gradually enlarging in size on a serial follow up CT.

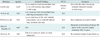

To the best of our knowledge, only four cases of a malignant PEC tumor of the lung are reported in English literature (Table 1) (4, 7-9) and not much is known about the radiologic findings of a malignant pulmonary PEC tumor until now. Our case has three unique points compared with the previous reports.

First, it is the first pathology proven malignant PEC tumor which presented with primary lung mass and lung to lung metastasis. Multiple lung metastases in this case are related with the problems of management which will be discussed later.

Second, the presence of calcifications within a PEC tumor has also not been reported in previous reports. In our case, we could observe multifocal curvilinear calcifications within the tumor. It is known that PEC tumors have rich vascular stroma and thus, we presume that the calcifications are dystrophic in nature.

Third, it is the first case demonstrating PET CT findings in a malignant pulmonary PEC tumor. According to our knowledge, there had been only one previous case report of a benign pulmonary PEC tumor with increased 18F-FDG uptake (SUVmax of 2.0) (10). Our case showed higher SUVmax of 4.4. This high metabolic activity may be associated with a more aggressive and malignant nature in our case.

In general, pulmonary PEC tumors appear as a round shaped, smooth contoured, peripheral parenchymal nodule or mass without evidence of cavitation or calcification and most are benign (4). However, our case showed aggressive features such as large size and metastatic lesions on imaging with negative immunohistochemical-staining result for HMB45 (which is positive in 75% of all PEComas), causing definitive diagnosis to be difficult.

It is thought that PECs can modulate their morphology and immunophenotype (Fig. 1H); the cells can show muscular features with a spindle shape and a stronger positivity for actin than for HMB45 (pathway 1) or they can have epithelioid features with a strong positivity for HMB45 and a mild, if any, reaction for actin (pathway 2) (5). In our case, the tumor cells presented with muscular features (as a result of pathway 1) and showed immunopositivity for S-100 and SMA rather than HMB45. The exceptionally malignant clinical features shown in our case, although elucidated further in the future, may be speculated to be related to this unusual feature of perivascular epitheloid cells.

Recently, Folpe et al. (11) reported a significant association between tumor size > 5 cm, infiltrative growth pattern, high nuclear grade, necrosis and mitotic activity > 1/50 HPF and recurrence and/or metastasis of PEC tumors. Although this study included 26 cases of PEComas of soft tissue and gynecologic origin, we think this approach is the best available for all cases of PEC tumor at the moment. In our case, the lung PEC tumor was larger than 5 cm in diameter and showed high mitotic activity (Ki-67 score of 10%), thus compatible and corroborative with the criteria of recurrent or metastatic nature proposed by Folpe et al. (11).

Another challenge in our case was its management. In our case, despite of histopathologically confirmed low grade malignancy for the primary tumor, the tumor presented with highly malignant clinical features. The metastatic nodules in both lungs increased in size. For example, the lesion in RLL increased more than 220% over six months. Even though an additional metastasectomy was performed after 1 year from the initial operation, there are still remaining metastatic lesions and they are gradually enlarging in size on a serial follow up CT.

The present case of a 63-year-old man elucidates the difficulties in diagnosis, management, associated poor outcomes, and the necessity for more advanced chemotherapeutic options. Until now, surgical resection has been accepted as the only curative approach for a primary PEC tumor at presentation as well as for local recurrence and metastasis, as chemotherapy and radiotherapy have not demonstrated significant benefits (2). To our knowledge, an optimal treatment strategy does not exist for such an aggressive PEC tumor case at the moment. Only recently limited studies have reported encouraging results of targeted therapy after oral administration of a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor in a metastatic PEC tumor of retroperitoneum, kidney and uterine cervix (12). Until now, there is no previous application of the chemotherapy, immunotherapy or targeted therapy for this extremely rare malignant PEComa of the lung with metastasis and further study is required for rational usage.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Imaging and pathologic findings of 63-year-old man with malignant pulmonary PEComa (A-G) and modulation of PEC (H)

Chest radiography revealing huge mass in left mid to lower lung field, abutting mediastinal structures (A). Computed tomography demonstrating mass attached to posteromedial aspect of left lower lobe with air-bronchogram (arrow) in peripheral portion and without displacement of bronchovascular bundle adjacent lung parenchyma (B), which indicates lung parenchymal lesion. Several metastatic nodules (arrowheads) in both lungs (B, C). Well circumscribed, heterogeneously enhancing mass (D) containing curvilinear calcifications (arrows, E). Positron emission tomography scan (F) showing hypermetabolic mass with SUVmax of 4.4. Specimen showing rounded or oval shaped tumor cells with abundant clear cytoplasm (histological examination), H&E × 400. Immunoreactivity for SMA and immunonegative for HMB45 of tumor cells (histological examination), × 200 (G). Concept of modulation of perivascular epithelioid cell in morphology and immunophenotype (H).

References

1. Liebow AA, Castleman B. Benign clear cell ("sugar") tumors of the lung. Yale J Biol Med. 1971; 43:213–222.

2. Selvaggi F, Risio D, Claudi R, Cianci R, Angelucci D, Pulcini D, et al. Malignant PEComa: a case report with emphasis on clinical and morphological criteria. BMC Surg. 2011; 11:3.

3. Martignoni G, Pea M, Reghellin D, Zamboni G, Bonetti F. PEComas: the past, the present and the future. Virchows Arch. 2008; 452:119–132.

4. Ye T, Chen H, Hu H, Wang J, Shen L. Malignant clear cell sugar tumor of the lung: patient case report. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:e626–e628.

5. Armah HB, Parwani AV. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009; 133:648–654.

6. Kim WJ, Kim SR, Choe YH, Lee KY, Park SJ, Lee HB, et al. Clear cell "sugar" tumor of the lung: a well-enhanced mass with an early washout pattern on dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography. J Korean Med Sci. 2008; 23:1121–1124.

7. Sale GE, Kulander BG. 'Benign' clear-cell tumor (sugar tumor) of the lung with hepatic metastases ten years after resection of pulmonary primary tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1988; 112:1177–1178.

8. Parfitt JR, Keith JL, Megyesi JF, Ang LC. Metastatic PEComa to the brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2006; 112:349–351.

9. Yan B, Yau EX, Petersson F. Clear cell 'sugar' tumour of the lung with malignant histological features and melanin pigmentation--the first reported case. Histopathology. 2011; 58:498–500.

10. Zarbis N, Barth TF, Blumstein NM, Schelzig H. Pecoma of the lung: a benign tumor with extensive 18F-2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007; 6:676–678.

11. Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, Fisher C, Balzer BL, Weiss SW. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29:1558–1575.

12. Wagner AJ, Malinowska-Kolodziej I, Morgan JA, Qin W, Fletcher CD, Vena N, et al. Clinical activity of mTOR inhibition with sirolimus in malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: targeting the pathogenic activation of mTORC1 in tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:835–840.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download