Abstract

A solid-pseudopapillary tumor (SPT) of the pancreas is known as a low grade malignant tumor with a good prognosis; therefore, surgical intervention is necessary. A 14-year-old boy presented with a large pancreatic SPT and three hepatic metastases. The patient and his family refused surgery. Two serial follow-up CT scans over a period of 13 years demonstrated almost complete disappearance of the pancreatic tumor and three hepatic metastases without relevant treatment. Although there have been a few reports of spontaneous healing of SPT, there has been no report regarding spontaneous disappearance of SPT and distant metastasis. Herein, we report on the spontaneous regression of a large SPT and the disappearance of three hepatic metastases.

A solid pseudopapillary tumor (SPT) is a relatively uncommon neoplasm of the pancreas with a relatively high prevalence in young women (1). Most SPTs are limited to the pancreas, and an adequate surgical intervention results in long term survival (2-4). However, 10-15% of patients will develop metastatic disease (5). The natural course of SPT has not yet been clarified due to a lack of reports based on a long follow-up period. Recently, a few case reports have described natural reduction of SPT in pediatric patients (6-8); however, the tumors in those cases were confined to the pancreas and were relatively small (less than 5 cm). We herein report on an unusual case of a large SPT with liver metastases in which the tumor showed a marked decrease in size from 11 to 3 cm and demonstrated a complete disappearance of hepatic metastases over a period of 13 years without any relevant treatment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing the spontaneous shrinkage of SPT and the disappearance of distant metastasis.

A 14-year-old boy presented with continuous upper abdominal pain after falling down. Physical examination revealed a soft, flat abdomen with no palpable mass or tenderness, and no enlargement of the superficial lymph nodes. Laboratory data upon admission showed no abnormalities in serum hormone levels, including those of insulin, glucagon, gastrin, secretin, and vasoactive intestinal peptide. The same is true for levels of tumor markers, including those of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen.

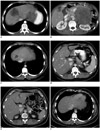

Abdominal CT (Fig. 1A, B) demonstrated an encapsulated mass measuring 11 × 10 cm, and located in the left upper quadrant. The mass showed central low attenuated and peripheral high attenuating areas. After contrast administration, solid components showed heterogeneous enhancement due to irregular necrosis. The portal vein, stomach, and the body of the pancreas were displaced anteriorly, while the celiac axis was displaced upward, and the left kidney was displaced posteriorly. The tail of the pancreas was not delineated, suggesting that the mass originated from the pancreatic tail. Marked dilatation of the pericapsular vein was noted. No involvement of the bile duct or the portal vein and no enlarged lymph node were observed. In the right hepatic lobe, there were three masses with maximum diameters of 6.0 cm, 5.3 cm, and 3.5 cm, respectively. They showed the same CT features as those of the primary mass. SPT with hepatic metastasis topped the list of differential diagnoses.

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy of the pancreatic mass revealed "a solid and cystic pseudopapillary neoplasm". Clinicians planned a tumor resection and the right hemi-hepatectomy and right portal vein embolization was performed for induction of left hepatic hypertrophy. Angiography demonstrated no hypervascularity in the pancreatic tumor and liver metastases. However, the patient and his family refused surgery and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Five years later, the patient visited our hospital in order to obtain a medical certificate. CT (Fig. 1C, D) showed that the tumor had decreased in size from 11 to 4.5 cm and contained foci of calcification. The hepatic masses had almost disappeared, and only one 2-cm mass remained at the right hepatic dome. During the five-year period, he had never undergone any relevant treatment.

The last follow-up CT, which was performed 13 years later (Fig. 1E, F), showed that the size of the pancreatic mass was 3 cm and that the residual hepatic mass had completely disappeared. Presently, the patient is doing well and will continue with follow-ups in our hospital.

Solid-pseudopapillary tumor is an uncommon neoplasm of the pancreas, accounting for 1-2% of all exocrine pancreatic tumors, and usually occurs in young females in their second or third decade of life (1, 9). SPT is generally considered a tumor with a low malignancy potential. Most cases of SPT of the pancreas are limited to the pancreas and cured by complete resection (2-4). Thus, surgical resection has been considered the treatment of choice. Of all SPTs, approximately 6% were reported to invade surrounding organs and approximately 10-15% developed distant metastasis. The most frequent organ of metastasis is the liver (5). Typically, CT shows a well-encapsulated heterogeneous mass in the pancreas with both solid and cystic components as in our case (10). Thus, when these features are encountered in a young female patient, this neoplasm should be a strong diagnostic consideration.

To the best of our knowledge, there have been three articles regarding spontaneous regression of SPTs of the pancreas and the patients were all pediatric patients. Nakahara et al. (6) reported a case showing shrinkage of a tumor from 4.5 cm to 1.5 cm during a 10-year follow-up period, and Suzuki et al. (7) reported on a case showing shrinkage of a tumor from 5 cm to a non-measurable size over a six-year period. Also, Hachiya et al. (8) demonstrated two cases of vanishing SPTs measuring 3 cm and 4 cm, respectively on long term follow-up. The authors explained that the natural shrinkage resulted from degenerative change, including hemorrhage and necrosis, followed by absorption. SPTs of these cases were primary pancreatic masses, which were relatively small (less than 5 cm). In our case, both the primary tumor and the three hepatic masses were large. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of the natural regression of a large SPT and multiple distant metastases.

The patient did not undergo any relevant treatment during the follow-up period except for right portal vein embolization for induction of left hepatic lobe hypertrophy. Because the tumors were hypovascular, as shown by minimally enhancing tumors on contrast-enhanced CT and no tumor staining on angiography, we do not think that the portal vein embolization had an effect on shrinkage of the hepatic tumors. In a previous similar case report, the authors underwent portal vein embolization for delayed hemihepatectomy as in our case and a 3-month follow-up CT showed no shrinkage of hepatic metastases (11). Although it was a relatively short-term follow-up, this report is supporting our speculation that the portal vein embolization was not impacted on the tumor regression. Therefore, in the present case, we believe that regression of the primary and metastatic tumors should be considered spontaneous.

Given the paucity of the reported cases, the management of metastatic disease is, to date, poorly defined. Vollmer et al. (11) reported a case with a pancreatic SPT with liver metastases in an adult patient and the case was managed by aggressive surgical treatment due to an indeterminate pathology. In fact, because surgical resection for even solitary pancreatic SPT has been recommended considering the possibility of malignant potential (2-4), their management could be acceptable. However, under the absence of established treatment guidelines in the pediatric patient, the clinical course of the patients in this case report indicates that SPTs are histopathologically-confirmed, especially in pediatric patients. Also, when some tumor regression is observed, a "wait and see" strategy is worth a try to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Serial CT images of 14-year-old with continous upper abdominal pain after falling down.

A, B. Contrast-enhanced CT images demonstrate 11 × 10 cm encapsulated mass in left upper quadrant showing slightly heterogeneous enhancement. Mass comes in direct contact with anteriorly displaced pancreatic body (arrowhead). Note marked dilatation of pericapsular veins (arrows). Two hepatic metastatic tumors, measuring 6.0 cm and 3.5 cm, respectively, are observed in right hepatic lobe. Another tumor, measuring 5.3 cm was observed in right hepatic lobe on another CT image (not shown). C, D. Contrast-enhanced CT images 5 years later show that primary tumor has decreased to 4.5 cm in longest diameter (arrow), and contains several small calcific foci. Small residual mass, measuring 2 cm is observed at right hepatic dome. E, F. CT image 13 years later shows further decrease in pancreatic mass to 3 cm (arrow), with more prominent calcification. Small mass at right hepatic dome has completely disappeared. SMV = superior mesenteric vein

References

1. Lam KY, Lo CY, Fan ST. Pancreatic solid-cystic-papillary tumor: clinicopathologic features in eight patients from Hong Kong and review of the literature. World J Surg. 1999. 23:1045–1050.

2. Reddy S, Cameron JL, Scudiere J, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, Ahuja N, et al. Surgical management of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas (Franz or Hamoudi tumors): a large single-institutional series. J Am Coll Surg. 2009. 208:950–957. discussion 957-959.

3. Sanfey H, Mendelsohn G, Cameron JL. Solid and papillary neoplasm of the pancreas. A potentially curable surgical lesion. Ann Surg. 1983. 197:272–275.

4. Zinner MJ, Shurbaji MS, Cameron JL. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasms of the pancreas. Surgery. 1990. 108:475–480.

5. Martin RC, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF, Conlon KC. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a surgical enigma? Ann Surg Oncol. 2002. 9:35–40.

6. Nakahara K, Kobayashi G, Fujita N, Noda Y, Ito K, Horaguchi J, et al. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas showing a remarkable reduction in size over the 10-year follow-up period. Intern Med. 2008. 47:1335–1339.

7. Suzuki M, Shimizu T, Minowa K, Ikuse T, Baba Y, Ohtsuka Y. Spontaneous shrinkage of a solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: CT findings. Pediatr Int. 2010. 52:335–336.

8. Hachiya M, Hachiya Y, Mitsui K, Tsukimoto I, Watanabe K, Fujisawa T. Solid, cystic and vanishing tumors of the pancreas. Clin Imaging. 2003. 27:106–108.

9. Papavramidis T, Papavramidis S. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2005. 200:965–972.

10. Buetow PC, Buck JL, Pantongrag-Brown L, Beck KG, Ros PR, Adair CF. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas: imaging-pathologic correlation on 56 cases. Radiology. 1996. 199:707–711.

11. Vollmer CM Jr, Dixon E, Grant DR. Management of a solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas with liver metastases. HPB (Oxford). 2003. 5:264–267.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download