Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to show the clinical and radiologic features of a variety of diffuse, infiltrative breast lesions, as well to review the relevant literature. Radiologists must be familiar with the various conditions that can diffusely involve the breast, including normal physiologic changes, benign disease and malignant neoplasm.

The breast can be diffusely affected by a variety of specific and unique disorders, including benign disorders that are closely related to physiologic changes and inflammatory and infectious diseases, as well as by benign and malignant tumors. The clinical manifestations include unilateral or bilateral breast enlargement with/without a palpable masses, shrinkage and breast asymmetry. Thus, knowledge about the etiologies of the entities that cause size changes or asymmetry of the breasts and their typical appearances can help in making an accurate diagnosis. In this article, we discuss and illustrate a spectrum of diffuse infiltrative breast lesions that range from normal physiologic changes to pathologic conditions.

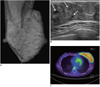

During pregnancy and lactation, the breast undergoes considerable changes in response to increased levels of circulating hormones such as estrogen, progesterone and prolactin. The physiologic changes associated with pregnancy and lactation makes it difficult to detect and evaluate breast masses both clinically and radiographically (1). On mammography, the breast of a lactating or pregnant woman appears very dense, heterogeneously coarse, nodular and confluent, with a marked decrease in adipose tissue and a prominent ductal pattern (Fig. 1A). The ultrasonography taken during pregnancy or lactation is characterized by diffuse, inhomogeneous hypoechogenicity with a prominent ductal system and increased vascularity (Fig. 1B).

The pattern of uptake and excretion of 18F-FDG in the lactating breast has been reported by some articles (2, 3). Hicks et al. (2) have reported on the unilateral breast uptake in the women who used only one breast for nursing and the loss of metabolic uptake of FDG in the unused breast, the same as was seen in our cases (Fig. 1C). These findings indicate the influence of breast-feeding on the glandular uptake of FDG in the breast, which has implications for diagnosing breast cancer in the postpartum woman who is undergoing PET scanning (2).

Mastitis may occur in the puerperal or non-puerperal state. The most common causative organisms are staphylococcus and streptococcus, although tuberculosis may sometimes be encountered (4, 5). Clinically, these patients may present with a focal area of tenderness with associated erythema and induration. Breast abscess can be a complication of mastitis, and especially if treatment is delayed or it is inadequate (5).

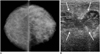

Mammography is not routinely performed for puerperal mastitis unless malignancy is suspected. The most common mammographic finding of mastitis is an irregular mass, whereas skin and trabecular thickening from breast edema is observed in rare cases (4) (Fig. 2A). Ultrasonography is very useful for detecting breast abscesses that are caused by complications of mastitis (5). Abscesses usually manifest as subareolar, focal, irregular hypoechoic or complex echoic masses with surrounding edema. However, in cases of severe mastitis, a diffuse abscess with surrounding edema can be seen (Fig. 2B). If there is no association of mastitis and abscess with pregnancy and lactation, or if there is inadequate resolution after antibiotic therapy, then these are indications for US-guided biopsy to exclude inflammatory breast carcinoma.

Granulomatous mastitis is a very rare inflammatory disease of an unknown origin that can clinically and radiographically mimic carcinoma (6). This disease usually affects women of childbearing age or those with a history of oral contraceptive use. It is pathologically characterized by chronic granulomatous inflammation of the lobules without caseous necrosis or evidence of microorganisms. The diagnosis of granulomatous mastitis is based on excluding other granulomatous reactions such as tuberculosis (7, 8). The reported mammographic features are focal asymmetry with no distinct margin or mass effect. Han et al. (6) reported the ultrasonographic features of granulomatous mastitis as multiple, irregular, clustered, often contiguous, tubular hypoechoic lesions. The lesions are usually located at the periphery of the breast, but a subareolar location or diffuse involvement can also be evident according to Lee et al. (9) (Fig. 3).

The primary treatment has classically been based on excisional biopsy with or without corticosteroid therapy. The prognosis is often good, but local recurrence has been reported (10).

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) is a benign proliferation of stromal cells, which are composed of myofibroblasts. The characteristic histologic appearance is anastomosing slit-like empty spaces lined by flattened myofibroblasts. Histologically, PASH can be mistaken for low-grade angiosarcoma and phyllodes tumor. PASH may be found incidentally in as many as 25% of all breast biopsy specimens. PASH is a benign lesion that is believed to be hormonally induced and is not thought to be associated with an increased incidence of malignancy (11).

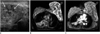

The typical imaging finding of PASH is a large, solid, oval mass with a well-defined border. Most reported cases of PASH have been small- to moderate-sized lesions. There have been two case reports (12, 13) describing rapidly growing tumoral PASH and both cases had similar imaging findings. These lesions manifested as a uniform and marked increase in the density of the breast without a discrete mass seen on mammography and compact stromal hyperplasia with conglomerated cystic spaces. In particular, Ryu et al. (12) have reported the mammographic and sonographic findings with the correlative magnetic resonance imaging of huge, bilateral, diffuse involvement of PASH (Fig. 4).

Breast edema can be caused by a variety of pathologic processes of benign or malignant diseases. It may occur with inflammatory breast carcinoma, lymphatic obstruction, mastitis, lymphoma, post-radiation changes or systemic conditions such as congestive heart failure and nephritic syndrome (14). Systemic problems, like congestive heart failure, occasionally result in unilateral rather than bilateral breast edema, although cases of bilateral breast edema have mostly been reported. Unilateral breast edema with lung cancer and ipsilateral pleural effusion has also been reported (15), the same as in one of our cases.

The mammographic findings of breast edema are skin thickening and increased parenchymal density with prominent interstitial markings (Fig. 5). On ultrasonography, it presents as marked skin thickening and increased echogenicity of the subcutaneous fat layer with a reticular anechoic structure, which is suggestive of dilated lymphatics.

Hemangiomas are benign vascular tumors of two common types (capillary or cavernous), depending on the size of the involved vessels.

According to Rosen and colleagues (16, 17), hemangiomas are classified into two groups: diffuse hemangiomas (angiomatosis) and localized hemangiomas. The localized hemangiomas are subdivided into four types: 1) perilobular, 2) parenchymal, 3) nonparenchymal or subcutaneous and 4) venous hemangiomas.

Most often, a hemangioma is superficially located either subdermally or within the subcutaneous tissues (18) (Fig. 6). Image-guided biopsy appears to be sufficiently reliable to rule out any malignant or premalignant component and to avoid surgical excision if this is clinically appropriate (19). Bleeding complications occasionally occur, but these can be manageable with manual compression.

Inflammatory breast carcinoma is a rare, highly aggressive form of primary breast cancer that comprises 1-6% of all the cases of breast cancer. It is associated with a poor prognosis because of the likelihood that it has already micro-metastasized at the time of diagnosis. Pathologically, any subtype of primary breast carcinoma may be present, but the dermal lymphatic vessels must be involved (20, 21).

Clinically, inflammatory breast carcinoma is characterized by the rapid onset of swelling and enlargement of the breast. The overlying skin remains intact, but there is erythema that is often combined with a "peau d'orange" texture, local tenderness, induration and warmth.

The imaging finding of inflammatory breast carcinoma is breast edema with an inflammatory pattern with or without a mass on mammography and sonography (Fig. 7A, B). Ultrasonography is helpful not only for depicting masses that are masked by the edema pattern, but also to demonstrate skin invasion and axillary involvement. The differential diagnoses of inflammatory breast cancer include non-puerperal mastitis, locally advanced breast cancer and primary breast lymphoma, and all of which may result in skin thickening, diffuse breast enlargement and edema. The MRI features of inflammatory breast carcinoma are skin thickening and a reticular/dendritic pattern of enhancement (Fig. 7C). A single PET study of seven patients with inflammatory breast carcinoma demonstrated diffusely increased or intense foci of increased uptake in enlarged breasts with increased skin uptake (22) (Fig. 7D).

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is the second most common breast malignancy, and it accounts for approximately 10% of all breast cancers. ILC spreads through the breast parenchyma by means of diffuse infiltration of single rows of malignant cells in a linear fashion around the non-neoplastic ducts. This infiltration causes little disruption of the underlying anatomic structures, and it generates little surrounding connective tissue reaction (23).

The detection of ILC on mammography and ultrasonography may be difficult because of its growth pattern and the resulting low density of the lesion.

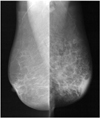

A higher incidence of subtle mammographic findings, such as architectural distortion, asymmetry and an irregular mass and especially a mass of lower or equal density compared to that of the surrounding parenchyma, or a decrease in breast size, have been reported as findings of ILC instead of a discrete mass (24) (Fig. 8A).

According to Butler et al. (25), the most common ultrasonographic finding was a hypoechoic, heterogeneous mass with irregular or indistinct margins and posterior acoustic shadowing (Fig. 8B).

If ILC is strongly suspected or if ILC is confirmed and breast conservation is favored, then performing MRI can be considered to assess the extent of tumor and to obtain additional information about multifocality and multicentricity (Fig. 8C, D).

Metastatic involvement of the breast is relatively rare and this accounts for approximately 1% to 3% of all breast malignancies. Spread of malignancy from the contralateral breast accounts for most of these metastases. The most recent review of the literature by Vizcaino et al. (26) showed the following as the commonest primary tumor sources, in order of decreasing frequency: lymphoma (Fig. 9), melanoma, rhabdomyosarcoma (Fig. 10), lung tumors and ovarian tumors. Metastases to the breast were found as a single mass, multiple masses or as diffuse infiltration. Metastasis to the breast may occur by two distinct routes: the lymphangitic and hematogenous routes.

Lymphangitic metastasis to the breast usually occurs across the anterior chest wall (transthoracic or cross-lymphatic metastasis) to the opposite breast, and the radiologic findings become indistinguishable from those of inflammatory carcinoma. This commonly occurs from contralateral breast cancer, stomach cancer and ovarian cancer (27, 28). The mammographic findings of lymphangitic metastasis are skin thickening and increased density in the subcutaneous fat tissue and the breast parenchyma (Fig. 9A). On ultrasonography, these metastases display swelling and inhomogeneously increased echogenicity in the subcutaneous fat layer and the breast parenchyma (Figs. 9B, 10B). On MRI, lymphatic metastasis appears as high signals in areas of edema on the T2 weighted image (Fig. 9C) and as heterogeneous non-mass-like contrast enhancement on the post contrast T1 weighted image.

In contrast to lymphatic metastasis, hematogenous metastases on imaging manifest as a single mass or multiple masses with a paucity of associated microcalcification, spiculation or other signs of a surrounding desmoplastic reaction. These findings most commonly occur in cases of melanoma, and they can also occur in cases of leukemia and lung cancer (29).

The overall prognosis of patients with metastases to the breast is extremely poor. Moreover, metastases to the breast suggest advanced systemic disease.

Many conditions can diffusely involve the unilateral or bilateral breasts. Unfortunately, the mammographic and ultrasonographic findings are frequently nonspecific. In many instances, CT and MRI are complementary studies that provide useful information about these lesions. To differentiate between the many diseases that are potentially involved, the patient's clinical history, the previously performed procedures and detailed knowledge concerning unilateral/bilateral diffuse enlargement or asymmetry can help the thoughtful radiologist to arrive at an accurate diagnosis.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Lactating breast in 31-year-old woman with past history of thyroidectomy due to thyroid cancer. Patient was nursing her infant with only her left breast.

A. Mammogram shows asymmetrical enlargement of left breast with diffuse increase in density. B. Ultrasonogram of left breast reveals diffuse enlargement of glandular component with duct ectasia (arrows). C. FDG PET scanning shows diffuse and intense uptake in left breast (SUVmax = 4.7).

|

| Fig. 2Puerperal mastitis with abscess secondary to Staphylococcus hominis infection in 28-year-old lactating woman.

A. Mammogram shows diffuse increase in density and trabecular thickening of left breast. B. Ultrasonogram show irregular, hypoechoic fluid collections that suggest abscess (arrows). Note edematous change of overlying skin and subcutaneous fat.

|

| Fig. 3Granulomatous mastitis in 31-year-old woman who was currently breast feeding at two years' postpartum.

A. Mammogram shows asymmetric increased density in left breast. B. Ultrasonogram shows ill-defined, irregular tubular, heterogeneous hypoechoic lesion involving left breast (arrows). Note vascularity immediately adjacent to lesion on Doppler sonography.

|

| Fig. 4Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia in 47-year-old woman.

A. Ultrasonogram demonstrates heterogeneously hypoechoic lesion with scattered cystic spaces (arrows) involving entire left breast. B. MRI of breast shows scattered cystic spaces of high signal intensity (black arrow) between diffuse and nodular low signals (white double arrows) on fat-saturated HASTE T2 image (TR/TE = 1100/118, flip angle: 150°). C. Fibrous tissue with low signal intensity on T2 image (white double arrows in B) shows homogeneous enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1 weighted image with fat suppression. (Material in Fig. 4 is quoted from Ryu et al.'s case report, which was published in Korean J Radiology in 2010).

|

| Fig. 5Left breast edema associated with left lung cancer in 89-year-old woman.

Mammogram shows diffusely increased density with skin thickening and trabecular thickening of left breast.

|

| Fig. 6Hemangioma of left breast with long-standing reddish purple skin change in 70-year-old woman.

A. Mammogram shows diffusely increased density and trabecular thickening with enlargement of left breast. B. Ultrasonogram shows diffusely increased echogenicity of overlying subcutaneous fat layer of left breast.

|

| Fig. 7Inflammatory breast cancer in 52-year-old woman.

A. Mammogram shows diffusely increased density, trabecular thickening and skin thickening of left breast. B. Ultrasonogram of left breast shows marked skin thickening, subcutaneous edema and dilated lymphatic channels (arrows), which are all typical of breast edema pattern. C. Axial contrast-enhanced T1 weighted image shows diffuse, infiltrative, non-mass enhancement involving entire left breast (TR/TE = 5.1/2.5). D. FDG PET scanning shows diffuse uptake of right breast with focal uptake on overlying thicken skin (SUVmax = 2.3).

|

| Fig. 8Invasive lobular carcinoma in 50-year-old woman who presented with hardness and decrease in size of right breast.

A. Mammogram shows diffuse skin thickening and trabecular thickening of right breast. B. Ultrasonogram of right breast shows diffuse posterior acoustic shadowing without discrete mass. C, D. Sagittal (C) and axial (D) contrast-enhanced T1 weighted images, respectively, reveal non-mass enhancement involving nearly entire right breast (TR/TE = 4.2/2.0).

|

| Fig. 9Secondary lymphoma to breast in 78-year-old woman with left breast enlargement.

A. Mammogram shows diffuse increased opacity throughout entire left breast with skin thickening. Note enlarged lymph nodes in left axilla on left mediolateral oblique mammogram. B. Ultrasonogram shows diffuse skin and subcutaneous edema of left breast. C. Sagittal T2 weighted image shows diffuse breast edema of high signal intensity in left breast (TR/TE = 4000/81.9).

|

| Fig. 10Metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma to breasts in 30-year-old woman with bilateral enlargement of breasts. She had history of sinonasal rhabdomyosarcoma that was treated by chemotherapy and radiation therapy 21 months previously.

A. Chest CT scan shows dense parenchyma with subtle nodular infiltration in both breasts. B. Ultrasonogram shows heterogeneous, infiltrative hypoechoic lesion that occupies majority of breast parenchyma.

|

References

1. Hogge JP, De Paredes ES, Magnant CM, Lage J. Imaging and management of breast masses during pregnancy and lactation. Breast J. 1999. 5:272–283.

2. Hicks RJ, Binns D, Stabin MG. Pattern of uptake and excretion of (18) F-FDG in the lactating breast. J Nucl Med. 2001. 42:1238–1242.

3. Yasuda S, Fujii H, Takahashi W, Takagi S, Ide M, Shohtsu A. Lactating breast exhibiting high F-18 FDG uptake. Clin Nucl Med. 1998. 23:767–768.

4. Crowe DJ, Helvie MA, Wilson TE. Breast infection. Mammographic and sonographic findings with clinical correlation. Invest Radiol. 1995. 30:582–587.

5. Ulitzsch D, Nyman MK, Carlson RA. Breast abscess in lactating women: US-guided treatment. Radiology. 2004. 232:904–909.

6. Han BK, Choe YH, Park JM, Moon WK, Ko YH, Yang JH, et al. Granulomatous mastitis: mammographic and sonographic appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999. 173:317–320.

7. Fletcher A, Magrath IM, Riddell RH, Talbot IC. Granulomatous mastitis: a report of seven cases. J Clin Pathol. 1982. 35:941–945.

8. Going JJ, Anderson TJ, Wilkinson S, Chetty U. Granulomatous lobular mastitis. J Clin Pathol. 1987. 40:535–540.

9. Lee JH, Oh KK, Kim EK, Kwack KS, Jung WH, Lee HK. Radiologic and clinical features of idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis mimicking advanced breast cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2006. 47:78–84.

10. Van Ongeval C, Schraepen T, Van Steen A, Baert AL, Moerman P. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Eur Radiol. 1997. 7:1010–1012.

11. Ibrahim RE, Sciotto CG, Weidner N. Pseudoangiomatous hyperplasia of mammary stroma. Some observations regarding its clinicopathologic spectrum. Cancer. 1989. 63:1154–1160.

12. Ryu EM, Whang IY, Chang ED. Rapidly growing bilateral pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia of the breast. Korean J Radiol. 2010. 11:355–358.

13. Teh HS, Chiang SH, Leung JW, Tan SM, Mancer JF. Rapidly enlarging tumoral pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia in a 15-year-old patient: distinguishing sonographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings and correlation with histologic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2007. 26:1101–1106.

14. Kwak JY, Kim EK, Chung SY, You JK, Oh KK, Lee YH, et al. Unilateral breast edema: spectrum of etiologies and imaging appearances. Yonsei Med J. 2005. 46:1–7.

15. Toh CK, Leong SS, Thng CH, Tan EH. Unilateral breast edema in two patients with malignant pleural effusion. Tumori. 2004. 90:501–503.

16. Rosen PP. Vascular tumors of the breast. V. Nonparenchymal hemangiomas of mammary subcutaneous tissues. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985. 9:723–729.

17. Rosen PP. Vascular tumors of the breast. III. Angiomatosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985. 9:652–658.

18. Siewert B, Jacobs T, Baum JK. Sonographic evaluation of subcutaneous hemangioma of the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002. 178:1025–1027.

19. Mesurolle B, Sygal V, Lalonde L, Lisbona A, Dufresne MP, Gagnon JH, et al. Sonographic and mammographic appearances of breast hemangioma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008. 191:W17–W22.

20. Dershaw DD, Moore MP, Liberman L, Deutch BM. Inflammatory breast carcinoma: mammographic findings. Radiology. 1994. 190:831–834.

21. Ellis DL, Teitelbaum SL. Inflammatory carcinoma of the breast. A pathologic definition. Cancer. 1974. 33:1045–1047.

22. Baslaim MM, Bakheet SM, Bakheet R, Ezzat A, El-Foudeh M, Tulbah A. 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography in inflammatory breast cancer. World J Surg. 2003. 27:1099–1104.

23. Dixon JM, Anderson TJ, Page DL, Lee D, Duffy SW. Infiltrating lobular carcinoma of the breast. Histopathology. 1982. 6:149–161.

24. Krecke KN, Gisvold JJ. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: mammographic findings and extent of disease at diagnosis in 184 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993. 161:957–960.

25. Butler RS, Venta LA, Wiley EL, Ellis RL, Dempsey PJ, Rubin E. Sonographic evaluation of infiltrating lobular carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999. 172:325–330.

26. Vizcaíno I, Torregrosa A, Higueras V, Morote V, Cremades A, Torres V, et al. Metastasis to the breast from extramammary malignancies: a report of four cases and a review of literature. Eur Radiol. 2001. 11:1659–1665.

27. Chung SY, Oh KK. Imaging findings of metastatic disease to the breast. Yonsei Med J. 2001. 42:497–502.

28. Lee SH, Park JM, Kook SH, Han BK, Moon WK. Metastatic tumors to the breast: mammographic and ultrasonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2000. 19:257–262.

29. Arora R, Robinson WA. Breast metastases from malignant melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 1992. 50:27–29.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download