Bronchobiliary fistula (BBF) is an unusual disorder characterized by an abnormal communication between the biliary tract and the bronchial tree. It can develop as a complication of hepatic surgery and interventions, or can be associated with various hepatobiliary diseases such as hydatid disease, hepatic abscesses, liver metastases, biliary lithiasis, and acute cholecystitis (1-6).

Although history of bilioptysis is pathognomonic for BBF, imaging tests are often required to verify the diagnosis and to demonstrate the site of communication along with underlying disease and associated findings. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC), and hepatobiliary scintigraphy are the most commonly employed imaging modalities (1-3). MRC is a safe and non-invasive technique demonstrating biliary anatomy and providing information for treatment planning, whether endoscopic, percutaneous, or surgical (1, 2). Contrast-enhanced (CE) MRC using hepatobiliary contrast agents is a recently emerged technique with promising results with respect to its ability to visualize non-dilated bile ducts and biliary leaks (7-9). However, the use of CE-MRC in the detection of BBF has not been reported previously. We present the performance and utility of CE-MRC using gadoxetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA) in the comprehensive evaluation of bronchobiliary fistula developed secondary to a hydatid cyst.

CASE REPORT

A 56-year-old woman presented with a persistent cough and expectoration of a copious amount of greenish material consistent with biliary secretions (bilioptysis). Her complaints had started after a cholecystectomy nine months previously. A degenerated hydatid cyst was discovered in the dome of her liver during surgery. Laboratory findings were within normal limits other than slightly elevated lactate dehydrogenase and gamma-glutamyl transferase. An indirect hemaglutination test for a hydatid cyst was negative.

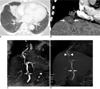

A chest radiograph showed right paracardiac infiltrates and a subsequent chest CT revealed mild stenosis in right middle lobe bronchus associated with distal subsegmental atelectasis and air bronchograms (Fig. 1A). Also present was an obscure hypodense lesion containing several punctate calcifications measuring 3 cm in liver segment 8 on CT (Fig. 1B). The lesion was extending anteriorly in the subdiaphragmatic region adjacent to the inferior surface of the right middle lobe. The continuity of diaphragm was interrupted at this location. Conventional and CE-MRC were performed using an 8-channel phased-array body coil on a 1.5T scanner (Signa Excite HD; General Electric, Milwaukee, WI). A conventional T2-weighted MRC demonstrated stenosis of the common bile duct as well as a biliary fistula extending to a subphrenic liver cyst, which communicated with the bronchial tree (Fig. 1C). To distinguish the communication between the biliary and bronchial tree, a CE-MRC was performed using breath-hold transverse and coronal 3-dimensional (3D) fat-suppressed gradient echo (LAVA, liver acquisition volumetric acceleration); (TR/TE, 4/1.8 milliseconds; flip angle, 12 degrees; section thickness, 3 mm; signal averages, 1; matrix, 288×192; scan time, 28 seconds) images, acquired 30 minutes after the intravenous administration of 25 µmol/kg gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA, gadoxetic acid; Primovist, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany). In the hepatobiliary phase images, a stricture of the common bile duct was seen. Moreover, contrast agent was seen concretely leaking from the ventrocranial branch of the right hepatic duct as well as into the subphrenic liver cyst and further transdiaphragmatically communicating with the bronchial tree (Fig. 1D). A biliary stent was placed endoscopically to close the fistula and to bridge the biliary stricture. The patient's symptoms were diminished after a successful biliary decompression.

DISCUSSION

Bronchobiliary fistula is an extremely rare clinical condition in which a bile leak penetrates the diaphragm into the bronchial tree, more frequently on the right side. In our case, transdiaphragmatic extension may likely have been caused by permeation of subdiaphragmatic inflammation as a result of a degenerated hydatid cyst. However, since the patient's complaints began after a cholecystectomy, a surgical injury with subsequent stenosis of the common bile duct might also be a contributory factor.

Bronchobiliary fistula may lead to a variety of pulmonary complications including recurrent chemical and bacterial pneumonitis, bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, and mediastinitis. Diagnosing a BBF is conducted based on the clinical symptom of bilioptysis (bile-stained sputum) (1-5). CT is the first line imaging technique for the investigation of the chest and upper abdomen. Although it rarely depicts the BBF, it may provide indirect findings such as subphrenic fluid collection, discontinuity of the diaphragm, bronchiectasis, atelectasis, or a pleural effusion (1-6). In our case, CT showed stenosis of the right middle lobe bronchus associated with distal atelectasis and bronchiectasis. Adjacent to right middle lobe was a hypodense lesion with punctuate calcification in the dome of the liver with obscuration of the diaphragm.

For patients with BBF, invasive procedures such as a percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography or ERCP have traditionally been performed in order to display the biliary anatomy. Conventional MRC performed without the use of contrast material is a rapid, safe, and non-invasive technique displaying the biliary tree. Moreover, it has been shown to be useful in the detection of BBF, and other biliary leaks; however, it lacks functional information (1, 2, 10). Therefore, conventional MRC only demonstrates indirect proof of bile leakage rather than directly depicting it. Another limitation of the technique is the inability to differentiate bile leaks from ascites as well as other perihepatic fluid collections. CE-MRC using hepatobiliary contrast agents is a recently developed technique that provides a combination of anatomic and functional information. It is particularly helpful in the concrete documentation of bile leaks since it directly depicts biliary excretion from injured ducts (9). Nevertheless, the use of CE-MRC in the comprehensive evaluation of bronchobiliary fistula has not been reported previously.

Currently, three hepatobiliary contrast agents are available for CE-MRC: mangafodipir trisodium (Mn-DPDP; Teslascan; GE Healthcare, Oslo, Norway), gadobenate dimeglumine (Gd-BOPTA; MultiHance, Bracco Imaging, Milan, Italy), and gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA, gadoxetic acid; Primovist, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany). Both gadobenate dimeglumine and Gd-EOBDTPA are incorporated into the hepatocytes by an anionic transport system after the vascular phase. Approximately 3-5% of the injected dose of gadobenate dimeglumine, and 50% of Gd-EOB-DTPA are excreted in the human biliary system (8, 11). The earlier onset (10-20 min) and longer duration (2 hours) of a high degree of contrast between the biliary system and liver for Gd-EOB-DTPA provides adequate hepatobiliary imaging within a shorter time span than Gd-BOPTA (8). In our case, a conventional T2-weighted MRC demonstrated possible communication between the subphrenic liver cyst and the bronchial tree. On the other hand, CE-MRC clearly delineated the leakage of contrast agent from the ventrocranial branch of the right hepatic duct into subphrenic liver cyst as well as the transdiaphragmatic communication with the bronchial tree. A stricture of the common bile duct was depicted for both techniques. In addition to adequate anatomic display, CEMRC also provides functional information similar to a 99mTc-HIDA scintigraphy. Thus, it can reliably differentiate bile leaks from other fluid collections such as ascites or seroma.

Treatment of BBF requires the removal of distal obstruction, reduction of flow through the fistula, or excision of the fistula. Nonoperative radiologic and gastrointestinal interventions via external and internal stenting reduce biliary obstruction and they should be the first therapeutic option in the management of BBF. Operative approaches should be reserved only when interventional procedures fail, or in patients with advanced concurrent diseases. In our case, the patient's symptoms were diminished after a successful biliary decompression by biliary stent placement.

In conclusion, Gd-EOB-DTPA enhanced upper abdominal MRI using 3D gradient echo techniques provides a robust tool for the visualization of the biliary tree in the hepatobiliary phase. Not only does CE-MRC display the biliary anatomy, it also provides functional information about physiologic or pathologic biliary flow. These properties make it an invaluable tool in the accurate detection of bronchobiliary fistula and bile leaks.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download