This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

A 38-year-old woman who had undergone pelvic lymphangioma resection two months previously presented with cough and dyspnea. Transthoracic echocardiography and CT demonstrated the presence of a mixed cystic/solid component tumor involving the inferior vena cava, heart and pulmonary artery. Complete resection of the cardiac tumor was performed and lymphangioma was confirmed based on histopathologic examination. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of lymphangiomatosis with cardiac and pelvic involvement in the published clinical literature.

Go to :

Keywords: Heart, US, Heart, CT, Lymphangiomatosis

Lymphangioma is a well-known benign tumor that occurs in the head and neck during childhood. However, cardiac lymphangioma is rarely encountered (

1,

2) and lymphangiomatosis involving the inferior vena cava (IVC), heart, pulmonary artery and pelvis has not been previously described. We report here a case of lymphangiomatosis that presented as a mixed cystic/solid component tumor in the IVC that traversed the right heart to the right pulmonary artery with a previous immediate history of another huge cystic mass in the pelvic cavity.

CASE REPORT

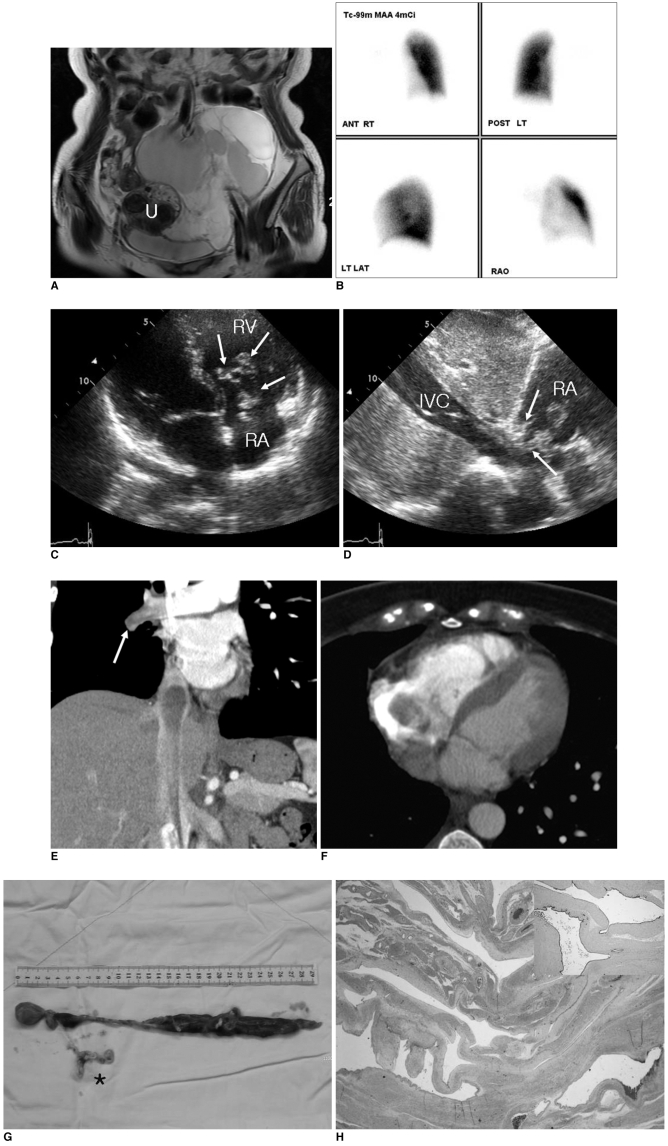

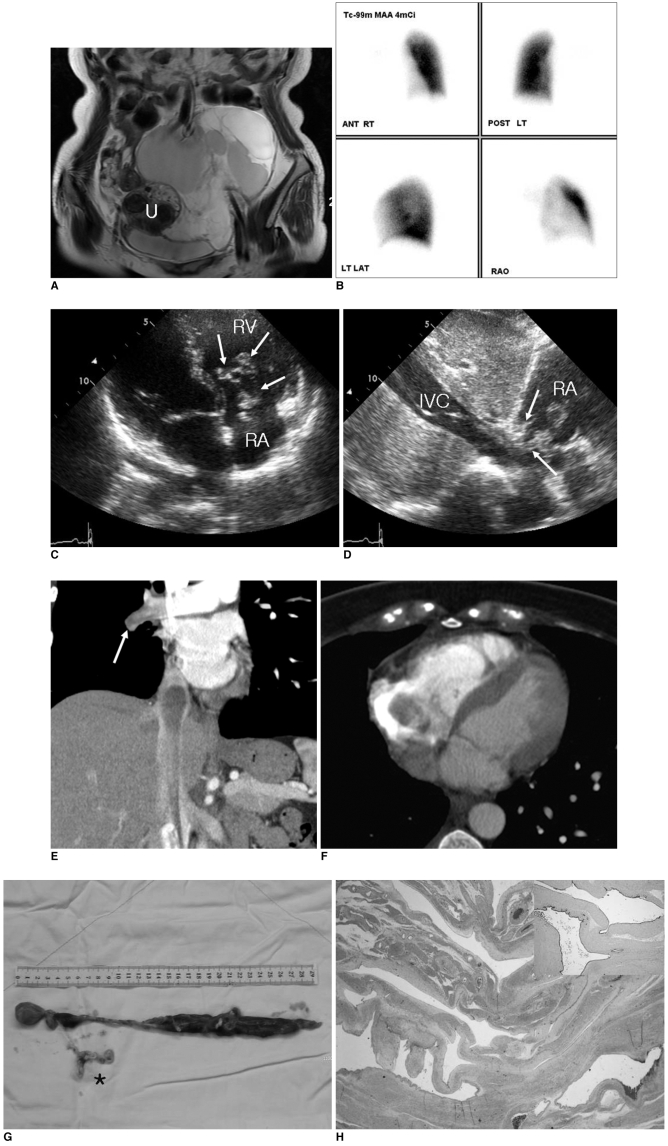

A 38-year-old woman with a history of pulmonary thromboemboli of seven months' duration was referred to our hospital for further evaluation. The patient had suffered from cough, dyspnea and transient hemoptysis. The patient had also undergone resection for a pelvic lymphangioma two months previously. At that time, pelvic MRI had demonstrated the presence of a large cystic mass with many septations and no involvement of the adjacent organs in the pelvis (

Fig. 1A).

| Fig. 1

Lymphangiomatosis in 38-year-old woman.

A. Coronal T2-weighted image shows large lobulated cystic mass with many septations in pelvic cavity. Preserved uterus (U) without tumor involvement is seen.

B. Perfusion lung scan with Tc-99m macroaggregated albumin shows perfusion defect in entire right lung, which was suspected to indicate complete occlusion of right pulmonary artery.

C, D. Transthoracic echocardiographs show heterogeneous echogenic mass with cystic component and incomplete coaptation of tricuspid valve, which resulted in tricuspid regurgitation (arrows in C). Mass extended to inferior vena cava (IVC) (arrows in D) (RA = right atrium, RV = right ventricle).

E, F. CT coronal (E) and axial (F) scans show non-enhanced mass with inferior vena cava and right atrial involvement, and hypoattenuating nodular lesion in right distal pulmonary artery (arrow in E).

G. Gross specimen excised from inferior vena cava, right heart and right pulmonary artery was seen as an elongated, reddish, 29 cm long mass with web-like tumor extension in right pulmonary artery (asterisk).

H. Hematoxylin & Eosin stained section of lesion shows dilated lymphatic channels with variable wall thicknesses. Based on immunohistochemical staining, tumor cells were positive for lymphatic vessel marker D2-40 (×40, insert).

|

A physical examination revealed no vital sign abnormalities. Levels of pro-BNP (B-type natriuretic peptide) and D-dimer were mildly elevated to 196.2 pg/ml (normal range, 0-97.3 pg/ml) and 486 µg/L (normal range, 0-324 µg/L), respectively. However, peak serum levels of creatine kinase-MB fraction (CK-MB), troponin T, other blood chemistry findings and blood counts were within normal ranges. An initial plain chest radiograph demonstrated reduced volume of the right hemithorax and a paucity of pulmonary vascular markings on the right side (not shown). Perfusion lung scanning using Tc-99m macro-aggregated albumin identified the absence of perfusion throughout the right lung, indicating occlusion of the right main pulmonary artery (

Fig. 1B). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) performed for the evaluation of persistent dyspnea demonstrated the presence of a mobile echogenic tumor adhering to chordae and papillary muscles of the tricuspid valve at the right atrium and right ventricle chordae. The tumor extended from the IVC into the right heart and caused tricuspid regurgitation (

Fig. 1C, D). Chest CT confirmed the presence of an elongated non-enhanced mass in the right chambers of the heart and in the IVC, with extension to the right distal pulmonary artery (

Fig. 1E, F). A median sternotomy was performed and the tumor was resected. Despite the presence of a neoplastic thrombus in the IVC, excision was straightforward except for resections of an adhesive chordal portion and a web-like tumor, which occluded the right distal pulmonary artery (

Fig. 1G). Postoperative recovery was excellent, and the patient was extubated the day after surgery and was discharged to the general ward on day-2 postoperatively. At seven days postoperatively, the patient underwent follow-up TTE that demonstrated the absence of any residual mass inside the cardiac chambers (data not shown). The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged at day-15 postoperatively.

Specimens from the IVC, right heart and right pulmonary artery were all diagnosed as cavernous lymphangiomas without features of malignancy. Grossly, the contiguous 29 cm long mass was a well-circumscribed, gray-white tumor with a soft, rubbery consistency (

Fig. 1G). Based on the histology, the tumor consisted of dilated lymphatic channels with variable wall thicknesses (

Fig. 1H). Lumina were lined with attenuated, bland endothelial cells. A few lymphocytes and rare lymphoid follicles were observed in the surrounding stroma, and a small number of disorganized bundles of smooth muscle were present in the walls of larger channels. Atypical features, such as, endothelial tufting, atypia and mitotic activity of lymphatic endothelium were absent, and based on immunohistochemical staining, tumor cells were positive for lymphatic vessel marker D2-40 (

Fig. 1H, insert) and CD31.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Although lymphangioma can occur in any region subserved by the lymphatic system (e.g., the head, neck, axilla, retroperitoneum, spleen, colon, intra-abdominal mesentery, esophagus, mediastinum and chest wall), cardiac manifestations of this disease entity are rare (

1-

3). In addition, cardiac and pelvic involvement, which we refer to as lymphangiomatosis, has not been previously described. The majority of reported cases of cardiac lymphangioma have occurred in children younger than 10 years (

1-

5), and symptoms appear to depend on sites and the extent of involvement, ranging from congestive heart failure, syncope, arrhythmia and palpitations to cardiac tamponade (

5).

Echocardiography is the initial imaging modality utilized to evaluate cardiac tumors, and subsequently, echocardiographic examinations that are more extensive provide detailed descriptions and allow for an accurate diagnosis. Recently, a technique based on enhanced CT has been developed and has been recommended as a better modality for the evaluation of the primary tumor and extracardiac extensions (

6). Furthermore, MRI can be a useful method to achieve a differential diagnosis. However, conventional coronary angiography can visualize tumor vascularity, but the modality is not considered a primary imaging method. In the described case, echocardiography and CT suggested the presence of a well-demarcated mass involving the IVC, heart and pulmonary artery, and low echogenicity and poor-enhancement resulted in suspicion of a cystic mass. At the time, cystic lymphangioma, myxoid degeneration of lymphangioma, hemangioma and intravenous leiomyomatosis were included in the differential diagnosis of the intracardiac cystic mass. Almost all patients with intravenous leiomyomatosis have a history of hysterectomy or myomectomy, different from lymphangiomatosis. In addition, the tumor showed enhancement and a well-circumscribed elongated solid mass.

Lymphangiomas arise from remnant lymphatic tissues, which fail to communicate with the normal lymphatic system, and may be detected in any body region. Generally, cardiac lymphangiomas are uncommon and mostly occur in the pericardium and other unusual sites, such as the myocardium (

5). However, intraatrial and intraventricular lymphangiomas as observed in the present case are rare (

1,

2). Flörchinger et al. (

1) described a cystic lymphangioma that originated from mitral valve tissue and caused mitral prolapse. Kim et al. (

2) described a cystic lymphangioma in the right atrium that was detected incidentally. In the present case, the lymphangioma originated from chordae and papillary muscles of the tricuspid valve, which caused tricuspid regurgitation. In addition, the growing mass occluded the right main pulmonary artery, mimicking thrombosis. Indeed, our patient had been treated unsuccessfully under the impression of pulmonary thromboembolism for some time.

Histologically lymphangiomas display dilated lymphatic vessels, lined by flattened endothelium among lobules of adipose, fibrous and lymphoid tissues. Lymphangioma requires surgical treatment to prevent fatal arrhythmia as previously mentioned. In addition, lymphangiomas may recur (

7), and therefore, complete resection is essential. However, adhesions to vital structures may make resection dangerous or impossible, and in such cases, high recurrence rates in totally excised and incompletely resected cases indicate a continuing need for effective treatment options to supplement surgery (

8). Other known treatment options include palliative surgical treatment or the use of sclerosing agents, such as OK-432 (

9).

Our case is interesting as it consisted of two lymphangiomas located at separate sites. One cystic tumor was detected in the pelvis, whereas the other tumor was attached to chordae and the tumor had progressed to the IVC and right pulmonary artery through the right cardiac chambers. Although lymphangioma rarely involves the heart, the tumor should be included in the differential diagnosis of cystic cardiac tumors.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download