Abstract

We report a case of transient abnormal myelopoiesis in a Down syndrome fetus diagnosed at 28+3 weeks of gestation that rapidly progressed to intrauterine death 10 days later. Fetal hepatosplenomegaly with cerebral ventriculomegaly, although not specific, may be a suggestive finding of Down syndrome with transient abnormal myelopoiesis. Prompt fetal blood sampling for liver function test and chromosomal analysis are mandatory for early detection and management.

Transient abnormal myelopoiesis (TAM) occurs in about 10% of newborns with Down syndrome, but prenatal diagnoses of fetal TAM has been rarely documented. Suspicion of this disorder arises when fetal hepatosplenomegaly with or without fetal hydrops is detected by prenatal ultrasonography (1-3). Percutaneous umbilical cord blood sampling is needed to diagnose TAM prenatally. Hematologic characteristics of TAM are markedly increased leukocyte level with blast cells in peripheral blood, which usually disappears spontaneously within a couple of months. Hepatosplenomegaly in TAM is thought to result from hepatic invasion of blast cells and/or secondary hepatic fibrosis (1). Hepatic failure and/or heart failure, and true leukemic change have been suggested as the main cause of death in fetuses with TAM (4). Here we present a report of fetal TAM in Down syndrome that resulted in a fatal outcome.

A 32-year-old Korean woman (gravida 3, para 2) was referred to our hospital at 28+3 weeks of gestation because of suspected fetal hepatomegaly. The course of this pregnancy had been uneventful. Her previous two pregnancies had resulted in full-term, uncomplicated vaginal births.

Transabdominal ultrasonogram and Doppler examination with a 4-MHz convex transducer (GE Kretzvolusom730, NY) were performed on referral. Decreased amniotic fluid (amniotic fluid index, 5) and a hydropic placental change were noted (maximum thickness, 6.2 cm). By biometry, the head circumference was demonstrated as being between 90 and 97 percentile size and the femur length was normal for gestational age, but abdominal circumference was increased due to hepatosplenomegaly (34.3 mm, larger than 97%) (5). A hypoechoic liver occupied nearly the entire enlarged abdomen and the length of liver was 7.2 cm (90th percentile) (6) (Fig. 1A). The stomach could not be detected and mild cerebral ventriculomegaly (1.1 cm) was demonstrated (Fig. 1B). The cardio-thoracic circumference ratio (62%) increased but cardiac anatomy was normal. No other structural abnormality was detected.

The peak systolic velocity (PSV) of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) increased (64.2 cm/s). Doppler flow patterns of all other vessels (uterine arteries, umbilical artery, umbilical vein, ductus venosus, inferior vena cava and four cardiac valves) were normal.

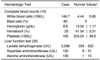

Percutaneous umbilical cord blood sampling (PUBS) was performed on the same day. The results are shown in Table 1. All serologic markers for intrauterine infection were negative (Toxoplasmosis, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes simplex, Rubella, Varicella Zoster, Epstein-Barr virus, Parvoviurs B19). The fetal blood count showed marked leukocytosis with 82% blast cells, moderate anemia and thrombocytopenia. Liver enzymes were markedly elevated. Fetal karyotyping revealed a trisomy 21 (47,XX,+21).

A follow up ultrasonography at 29+4 weeks' gestation revealed moderate amounts of ascites, pericardial effusion and skin edema (Fig. 1C). The PSV of the MCA further increased to 80.2 cm/s. Doppler velocimetry of other vessels including the umbilical artery, umbilical vein, ductus venosus and inferior vena cava revealed no abnormal findings. Subsequent fetal heart rate tracing showed minimal variability with shallow deceleration and fetal death in utero was diagnosed at 29+6 weeks' gestation.

Postmortem examination showed generalized cutaneous edema with pericardial effusion and ascites. Fetal nasal root was wide and flat. There were marked hepatomegaly (170 g; normal, 40±22 g) and splenomegaly (20 g; normal, 3.1±1.5 g) (7) (Fig. 1D). No other congenital malformations were detected and the placenta was hydropic with immature villi. Bone marrow was infiltrated with myeloblastic cells (Fig. 1E).

The association of Down syndrome and leukemia has been documented for over 50 years. Multiple studies have established the incidence of leukemia in Down syndrome patients to be 10-20-fold higher than that in the general population (8). About 10% of infants with Down syndrome have characteristic transient leukemoid reaction that disappears spontaneously within several months, therefore, this disorder has been designated TAM or congenital leukemoid reaction (9). Markedly elevated leukocyte levels together with circulating blast cells are characteristic hematological changes of an infant or fetus with TAM (2). Hemoglobin concentration is usually normal in TAM, but can be polycythemic (10) or anemic (1, 11). Our case showed a blood cell count that was moderately anemic, which was reflected as increased PSV of the MCA (12, 13).

Hepatosplenomegaly is a characteristic ultrasonographic sign for fetal TAM (1, 4, 11, 14, 15). Only one case of fetal TAM without hepatosplenomegaly has been reported (16). Our case showed marked hepatosplenomegaly on first ultrasonography, and fetal hydrops was evident on follow up ultrasonography. Hepatomegaly in TAM is thought to result from liver fibrosis, infiltration of blast cells to the liver and portal hypertension (1, 2). However, fetal hepatomegaly is a non-specific finding which can be associated with various conditions such as fetal anemia, congenital fetal infection, hepatic tumors, metabolic disorders, fetal congestive heart failure and macrosomia (3). So, umbilical cord blood sampling should be performed for differential diagnosis.

Ultrasonographic echogenicity of the enlarged liver in our fetus was markedly hypoechoic compared with meconium inside the colon, which is a characteristic finding in most fetuses with TAM. The mechanism for hypoechogenicity of the liver in TAM is not clear, but hepatic congestion secondary to increased extramedullary myelopoiesis of fetal liver has been suggested (3, 4, 14). Hepatic dysfunction of enlarged fetal liver was present in our case as in most fetuses with TAM (1, 10, 11, 15), which might be associated with liver fibrosis (1-4). In our case, the stomach shadow was not detected by ultrasound examination but postmortem study confirmed the normal stomach. Small or absent stomach shadow is presumed to be the result of collapse by enormous hepatosplenomegaly. Presently, there was mild cerebral ventriculomegaly, which is a characteristic ultrasonographic marker for Down syndrome (17). To our knowledge, of the 41 fetuses with TAM including our case that have been reported in the literature, only three fetuses with ventriculomegaly (9-11 mm) have been documented (2, 15). Although we did not perform a brain autopsy of the fetus, postmortem examination of the other two fetuses revealed brain atrophy with periventricular leukomalacia (2, 15). The pathogenesis of ventriculomeglay in fetuses with TAM appears to be different from that in Down syndrome fetuses without TAM. It seems that ventriculomegaly in Down syndrome fetuses may result from reduced brain tissue secondary to altered neuronal cell divisions early in developmental stage (18). However, ventriculomegaly in fetuses with TAM is thought to result from leukemic infiltration or local hypoxemia secondary to leukostasis (15). This can partly explain why fetal cardiotocogram shows minimal variability and/or late deceleration in all cases with subtle ventriculomegaly (2, 15). Fetal hydrops is another common ultrasonographic finding in TAM fetuses, which may be associated with a poorer prognosis (1). Numerous theories have been proposed regarding the pathogenesis of fetal hydrops; anemia that results in high output cardiac failure, congestive heart failure due to increased vascular resistance, local hypoxia secondary to leukostasis, portal venous hypertension due to hepatic enlargement, capillary damage by hypoxia, fetal hypoalbuminemia, increased vascular resistance, extramedullary megakaryoblastic proliferation, hepatic fibrosis and increased collagen synthesis by fibroblasts stimulated through cytokines (1-3).

In conclusion, fetal hepatosplenomegaly with cerebral ventriculomegaly, although not specific, may be a suggestive finding of Down syndrome with TAM. Prompt fetal blood sampling for liver function test and chromosomal analysis are mandatory for the early detection and planning of management. In addition, because ventriculomegaly as well as fetal hydrops may have poor prognostic implications, we suggest that ventriculomegaly should be recognized in the management of fetal TAM.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Transient abnormal myelopoiesis in Down syndrome fetus.

A. Longitudinal ultrasound scan of fetal abdomen shows hypoechoic liver occupying nearly entire enlarged abdomen. Liver length of 7.2 cm represents 90th percentile size.

B. Fetal cerebral ventriculomegaly measuring 1.1 cm is evident.

C. Oblique ultrasound scan of fetal abdomen. Skin edema (→) and ascites (*) are evident at 29+4 weeks' gestation.

D. Postmortem picture of fetus with hepatomegaly.

E. Myeloblastic cells infiltrating bone marrow (Hematoxylin & Eosin staining, ×40 magnification).

|

References

1. Hojo S, Tsukimori K, Kitade S, Nakanami N, Hikino S, Hara T, et al. Prenatal sonographic findings and hematological abnormalities in fetuses with transient abnormal myelopoiesis with Down syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2007. 27:507–511.

2. Smrcek JM, Baschat AA, Germer U, Gloeckner-Hofmann K, Gembruch U. Fetal hydrops and hepatosplenomegaly in the second half of pregnancy: a sign of myeloproliferative disorder in fetuses with trisomy 21. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 17:403–409.

3. Hamada H, Yamada N, Watanabe H, Okuno S, Fujiki Y, Kubo T. Hypoechoic hepatomegaly associated with transient abnormal myelopoiesis provides clues to trisomy 21 in the third-trimester fetus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 17:442–444.

4. Kikuchi A, Tamura N, Ishii K, Takakuwa K, Matsunaga M, Sudo N, et al. Four cases of fetal hypoechoic hepatomegaly associated with trisomy 21 and transient abnormal myelopoiesis. Prenat Diagn. 2007. 27:665–669.

5. Hadlock FP, Deter RL, Harrist RB, Park SK. Estimating fetal age: computer-assisted analysis of multiple fetal growth parameters. Radiology. 1984. 152:497–501.

6. Vintzileos AM, Neckles S, Campbell WA, Andreoli JW Jr, Kaplan BM, Nochimson DJ. Fetal liver ultrasound measurements during normal pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1985. 66:477–480.

7. Enid GB, Diane DS. Embryo and fetal pathology: color atlas with ultrasound correlation. 2004. NewYork: Cambridge University Press;665.

8. Fong CT, Brodeur GM. Down's syndrome and leukemia: epidemiology, genetics, cytogenetics and mechanisms of leukemogenesis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1987. 28:55–76.

9. Zipursky A, Brown EJ, Christensen H, Doyle J. Transient myeloproliferative disorder (transient leukemia) and hematologic manifestations of Down syndrome. Clin Lab Med. 1999. 19:157–167.

10. Ogawa M, Hosoya N, Sato A, Tanaka T. Is the degree of fetal hepatosplenomegaly with transient abnormal myelopoiesis closely related to the postnatal severity of hematological abnormalities in Down syndrome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004. 24:83–85.

11. Robertson M, De Jong G, Mansvelt E. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital leukemia in a fetus at 25 weeks' gestation with Down syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003. 21:486–489.

12. Pares D, Chinen PA, Camano L, Moron AF, Torloni MR. Prediction of fetal anemia by Doppler of the middle cerebral artery and descending thoracic aorta. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008. 278:27–31.

13. Scheier M, Hernandez-Adnrade E, Carmo A, Dezerega V, Nicolaides KH. Prediction of fetal anemia in rhesus disease by measurement of fetal middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004. 23:432–436.

14. Hartung J, Chaoui R, Wauer R, Bollmann R. Fetal hepatosplenomegaly: an isolated sonographic sign of trisomy 21 in a case of myeloproliferative disorder. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 11:453–455.

15. Baschat AA, Wagner T, Malisius R, Gembruch U. Prenatal diagnosis of a transient myeloproliferative disorder in trisomy 21. Prenat Diagn. 1998. 18:731–736.

16. Vimercati A, Greco P, Gentile A, Ingravallo G, Loverro G, Selvaggi L. Fetal liver hyperechogenicity on sonography may be a serendipitous sign of a transient myeloproliferating disorder. Prenat Diagn. 2003. 23:44–47.

17. Shipp TD, Benacerraf BR. Second trimester ultrasound screening for chromosomal abnormalities. Prenat Diagn. 2002. 22:296–307.

18. Haydar TF. Advanced microscopic imaging methods to investigate cortical development and the etiology of mental retardation. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2005. 11:303–316.

19. Forestier F, Daffos F, Galacteros F, Bardakjian J, Rainaut M, Beuzard Y. Hematological values of 163 normal fetuses between 18 and 30 weeks of gestation. Pediatr Res. 1986. 20:342–346.

20. Gozzo ML, Noia G, Barbaresi G, Colacicco L, Serraino MA, De Santis M, et al. Reference intervals for 18 clinical chemistry analytes in fetal plasma samples between 18 and 40 weeks of pregnancy. Clin Chem. 1998. 44:683–685.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download