Abstract

The coexistence of pneumothorax and pneumopericardium in patients with primary lung cancer is a very rare phenomenon. We report one such case, in which squamous cell carcinoma of the lung was complicated by pneumopericardium and pneumothorax. Several explanations of the mechanisms involved will be discussed.

Spontaneous pneumothorax is infrequently associated with primary lung cancer, and the estimated rate of coexistence is less than 0.05% (1, 2). The coexistence of pneumopericardium and lung cancer cited in the medical literature is less frequent (3-5). The concurrence of pneumopericardium and pneumothorax in patients with primary lung cancer is therefore, an extremely rare condition. To our knowledge, the literature in English contains only one documented report of combined pneumothorax and pneumopericardium complicating bronchogenic carcinoma (6). We report the case of a patient with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung who presented with concurrent pneumopericardium and pneumothorax.

A 53-year-old man with 70 pack-year history of cigarette smoking was admitted to our hospital with dyspnea on exertion. Two years earlier, the presence of double primary lung cancer was demonstrated in both upper lobes, and was diagnosed pathologically squamous cell carcinoma. Treatment included a course of preoperative chemotherapy followed by right and left upper lobectomy 19 and 11 months, respectively, prior to admission. Ten months before the current admission, the patient visited the hospital complaining of cough, fever, chill, and dyspnea. Pneumonic infiltration of the left lower lobe was detected radiographically, and aspergillosis was confirmed by bronchoscopic biopsy. His condition improved during an 8-week course of amphotericin-B and he was discharged.

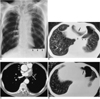

Two months before admission, he developed progressive dyspnea on exertion. Chest radiographs showed left pleural effusion, which increased during follow-up, and two months later he was admitted due to severe chest pain and progressive dyspnea. On admission, a chest radiograph (Fig. 1A) and CT (Fig. 1B) showed pneumopericardium and left hydropneumothorax, neither of which had been detected during previous radiographic studies. CT demonstrated an irregular-shaped soft tissue mass infiltrating the left atrium, and this suggested tumor recurrence (Fig. 1C). A suspected pericardial defect communicated with the pneumothorax (Fig. 1D). Diagnostic thoracentesis was performed 5 days after CT scanning, and analysis of the fluid revealed protein 38.38 g/L, glucose 5.328 mmol/L, Cl 109 mmol/L, LDH 428 IU/L, pH 7.35, and adenosine deaminase 19 IU/L, thus suggesting exudative fluid. The CEA level was not measured. White and red blood cell counts were both more than 1000 /mm3, suggesting malignant effusion, but cytologic and bacteriologic examination failed to demonstrate malignant cells or microorganisms. Bronchoscopy with cytologic and bacteriologic studies was also performed just after CT scanning, but no endobronchial lesion was apparent. Cytologic and bacteriologic studies were also negative. The patient was discharged without further diagnostic procedures or treatment.

In pneumopericardium, the roentgenographic findings are remarkable. The pericardial cavity is filled with air, which may extend inferiorly to the diaphragm, but superiorly, the presence of this is limited by the lower border of the aortic arch. The etiologies of pneumopericardium can be classified as one of four types (7-9): (a) iatrogenic - thoracentesis, post-sternal bone marrow biopsy, complicating endotracheal intubation; (b) pericarditis caused by gasforming microorganisms; (c) trauma; and (d) fistula formation between the pericardium and air-containing structures such as the bronchial tree, gastrointestinal tract, and pleural or peritoneal cavity. Spontaneous pneumopericardium is extremely rare with the majority of cases caused by iatrogenic or trauma-related factors. Esophageal and gastric ulcer or cancer, achalasia, esophageal diverticulum, tuberculosis, and brochogenic carcinoma can cause a fistula between the pericardium and air-containing structures.

Spontaneous pneumothorax usually results from the rupture of a cyst, bleb, or bulla into the visceral pleura. The suggested causes of pneumothorax are numerous, and include septicemia, pulmonary infarct, sarcoidosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and tumors. In patients with bronchogenic carcinoma, four pathogenetic mechanisms of spontaneous pneumothorax have been suggested (10): (a) the creation of a bronchopleural fistula, caused by an acute rupture of necrotic tumor tissue into a bronchus and the pleural space, which has been described as the most common cause; (b) the rupture of a subpleural bleb in an area of obstructive emphysema, or of an emphysematous bulla in a portion of the lung which is overexpanded and partially obstructed by the neoplasm, which is an important precipitating factor; (c) direct pleural invasion by the tumor; and (d) indirect effect caused by underlying emphysema.

Baydur and Gottlieb (6) have suggested three ways in which lung cancer can lead to pneumopericardium: (a) through the formation of a bronchopericardial fistula by a necrotic tumor which invades the pericardium directly; (b) through trauma caused by an artificial procedure such as bronchoscopy or thoracentesis; and (c) through the rupture of a bulla into the pericardium through a necrotic focus. In our case, the tumor directly invaded the left atrium, affecting both the pericardium and the mediastinal pleura, and thus creating a bronchopericardial fistula through the necrotic portion of the tumor. CT scans revealed diffuse centrilobular emphysema in the entire lung. Since the patient was also a heavy smoker, with a 70 pack-year history of cigarette consumption, pneumothorax could be related to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and the necrotic portion of the tumor could serve as a focus through which an overexpanded bulla could rupture, or preceding pneumothorax could progress into the pericardium. CT demonstrated that some portion of the pneumopericardium communicated with the pneumothorax, but unfortunately no tumor was observed there.

We have described a case in which lung cancer led to pneumopericardium and pneumothorax. The coexistence of pneumopericardium and spontaneous pneumothorax is extremely rare, but may be an unusual complication of lung cancer.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

A 53-year-old man with lung cancer after bilateral upper lobectomy.

A. Chest radiograph shows moderate amount of pneumopericardium (arrows) and left hydropneumothorax (arrowheads).

B. CT scan obtained at the level of the liver dome shows pneumopericardium (arrow) and left hydropneumothorax (arrowheads). Note the presepce of underlying centrilobular emphysema in both lower lobes.

C. Enhanced CT scan shows irregular-shaped soft tissue mass (arrow) infiltrating into the left atrium. Note the presence of pneumopericardium (arrowheads) and ipsilateral pleural effusion (open arrow).

D. CT scan obtained at a level below (B) shows suspected pericardial defect (arrow).

References

1. Wright FW. Spontaneous pneumothorax and pulmonary malignant disease: a syndrome sometimes associated with cavitating tumors. Clin Radiol. 1976. 27:211–226.

2. Dines DE, Cortese DA, Brennan MD, et al. Malignant pulmonary neoplasms predisposing to spontaneous pneumothorax. Mayo Clin Proc. 1973. 48:541–544.

3. Harris RD, Kostiner AI. Pneumopericardium associated with bronchogenic carcinoma. Chest. 1975. 67:115–116.

4. Ronge R, Roels P, DE Meirleir K., Schandevyl W, Dewilde P, Block P. Bronchogenic carcinoma: a rare cause of nontraumatic pneumopericardium. Acta Cardiol. 1983. 38:565–569.

5. Katzir D, Klinovsky E, Kent V, Shucri A, Gilboa Y. Spontaneous pneumopericardium: case report and review of the literature. Cardiology. 1989. 76:305–308.

6. Baydur A, Gottlieb LS. Pneumopericardium and pneumothorax complicating bronchogenic carcinoma. West J Med. 1976. 124:144–146.

7. Rigler LG. Pneumopericardium. JAMA. 1925. 62:118–120.

8. Shackelford RT. Hydropneumopericardium. JAMA. 1931. 96:187–191.

9. Toledo TM, Moore WL, Nash DA, et al. Spontaneous pneumopericardium in acute asthma: case report and review of the literature. Chest. 1972. 62:118–120.

10. Kabnick EM, Sobo S, Steinbaum S, Alexander LL, Nkongho A. Spontaneous pneumothorax from bronchogenic carcinoma. J Natl Med Assoc. 1982. 74:478–479.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download