INTRODUCTION

METHODS

Experiment animals

Isometric tension measurement

Drugs and chemicals

Statistical methods

RESULTS

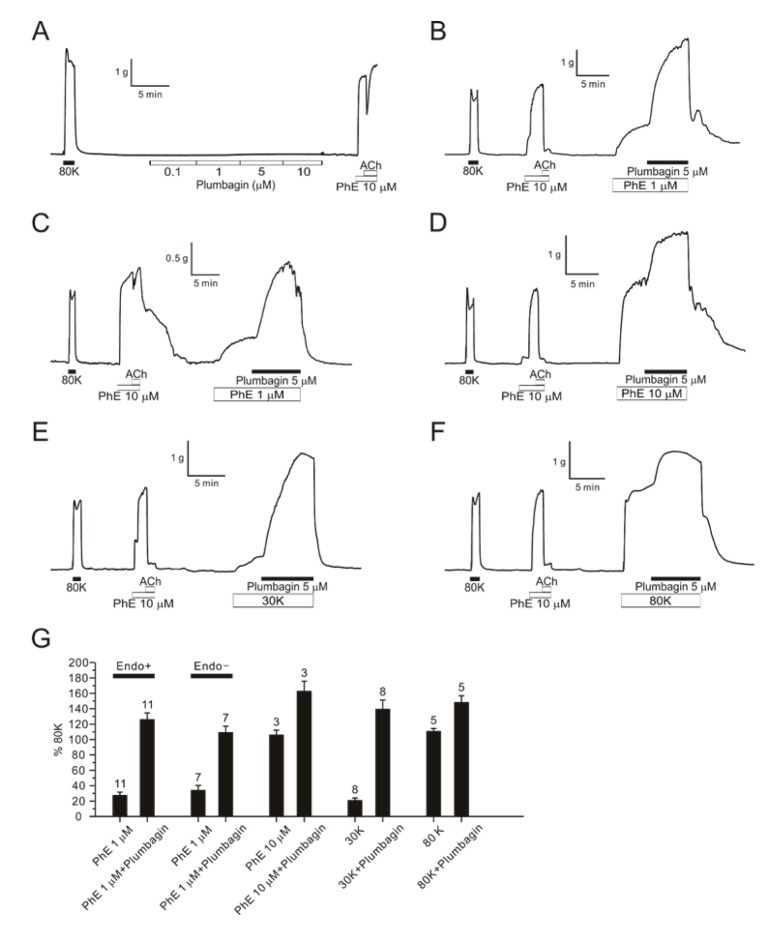

Biphasic augmentation of vasoconstriction by plumbagin

| Fig. 1Augmentation of DFA contractions by PhE and high K+-induced depolarization.An original trace of plumbagin dose response (0.1–10 µM) showing no effect without pretone in DFA (A, n=5). A representative trace of 5 µM plumbagin effect with 1 µM PhE pretone in endothelium intact DFA (B, n=11) and in denuded endothelium DFA (C, n=7). A raw trace of 5 µM plumbagin response in DFA with 10 µM PhE (D, n=3). Representative traces of 5 µM plumbagin in endo-intact DFAs pre-contracted with 30 mM potassium (E, n=8) and 80 mM potassium solution instead of PhE (F, n=5). The summarization of 5 µM plumbagin effect in endo-intact or denuded DFAs with various pretone conditions (G). Numbers of tested vessels are indicated above each bar graph.

|

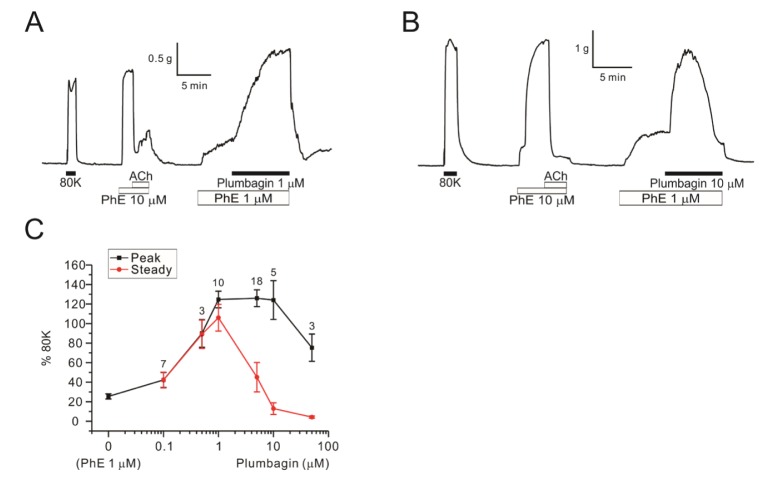

| Fig. 2Concentration-dependent dual effects of plumbagin on PhE-contraction in DFAs.Raw traces of 1 µM plumbagin (A, n=10) and 10 µM plumbagin (B, n=5) in DFAs. Plumbagin concentration response curves (0.1–50 µM) (C). The peak of contraction is indicated black line and steady state value of plumbagin treatment is indicated red line. Numbers of tested vessels are indicated above each symbol of peak response.

|

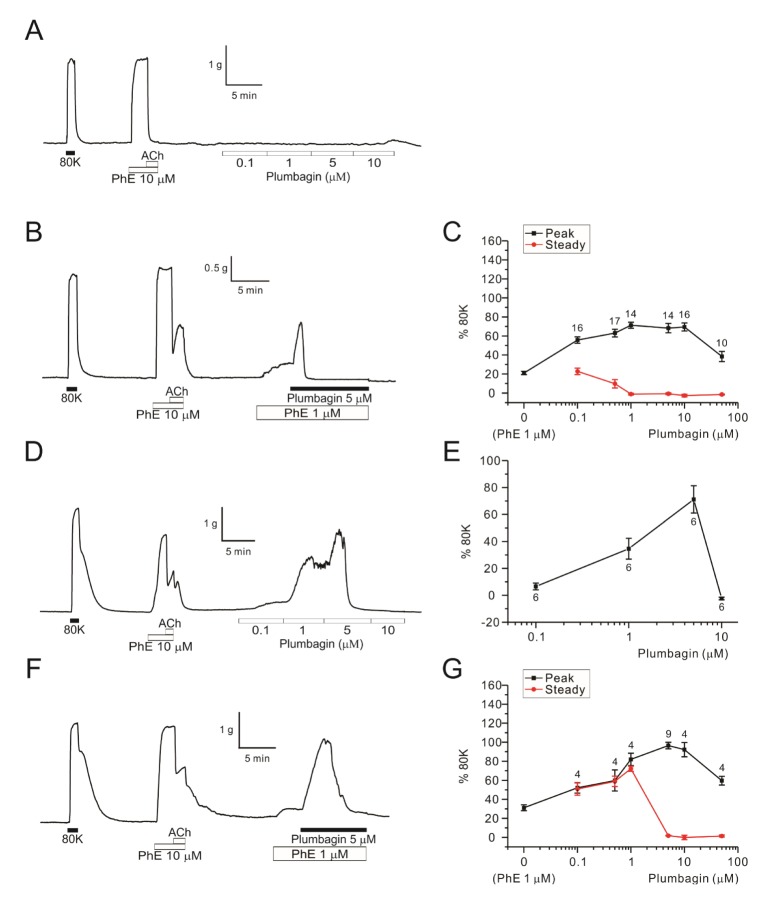

| Fig. 3Concentration-dependent dual effects of plumbagin on MAs and RAs.A raw trace of plumbagin dose response (0.1–10 µM) without PhE-pretone in endothelium-intact MA (A, n=5). A representative data of 5 µM plumbagin effect on MA pretreated with 1 µM PhE (B, n=14). Plumbagin concentration response curves (0.1–50 µM) in the MAs pretreated with 1 µM PhE (C). Peak of plumbagin contraction is indicated black and steady state of plumbagin response is indicated red. Numbers of tested vessels are indicated above each symbol of peak response (C). A representative trace of plumbagin dose response (0.1–10 µM) without PhE-pretone in endo-intact RA (D, n=6). The dose response curve of plumbagin without pretone in RAs (E). A representative data of 5 µM plumbagin with pre-contracted with 1 µM PhE-pretone in endothelium-intact RA (F, n=9). Plumbagin concentration response curves (0.1–50 µM) in RAs pretreated with 1 µM PhE (G). Each point represents mean of separate experiments and n numbers are indicated in the graphs, respectively.

|

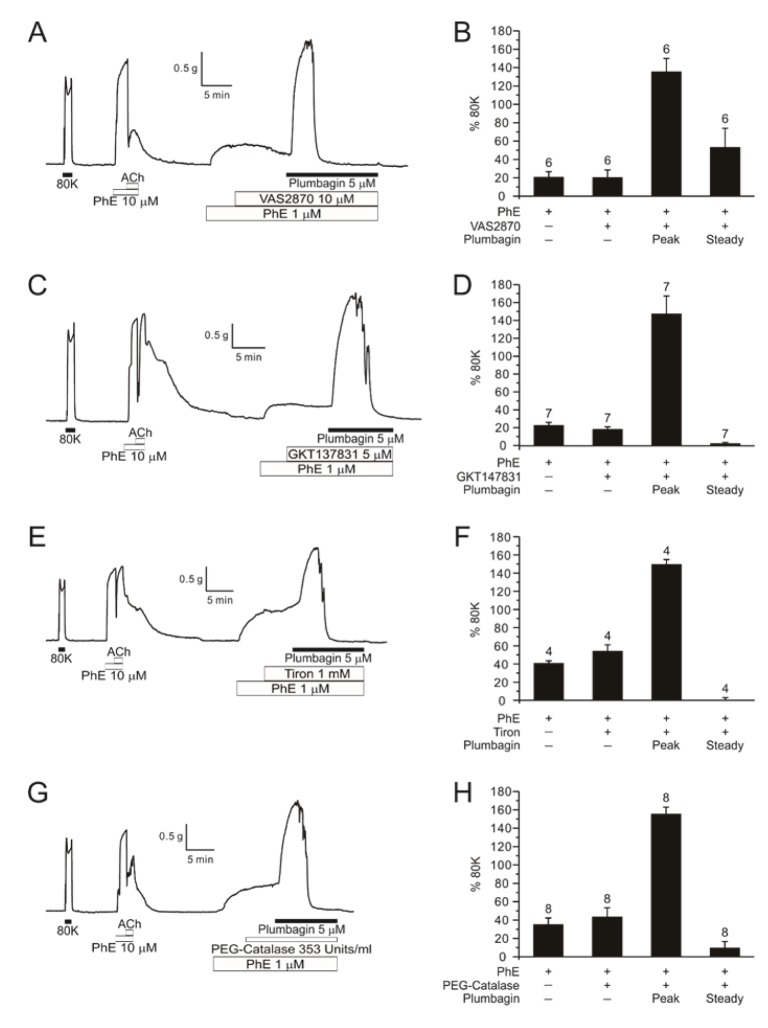

Mechanisms associated with the pro-contractile effects of plumbagin

| Fig. 4Effects of NOX inhibitors and ROS scavengers on plumbagin-contraction in PhE-treated DFA.A representative trace of 5 µM plumbagin after pre-treatment of 10 µM VAS2870 (NOX inhibitor) in DFA (A, n=6). A bar graph of normalized PhE, VAS2870, plumbagin and steady state (B). Values represent mean±SE and numbers of tested vessel are indicated above each bar. A representative data of 5 µM plumbagin after pre-treatment of 5 µM GKT137831 (NOX4 inhibitor) in DFA (C, n=7). Summarization of GKT137831 effect (D). Raw traces of 1 mM Tiron (n=4) and 353 Units/ml PEG-catalase (ROS scavengers) effect (n=8) before treatment of 5 µM plumbagin (E, G). Summary of the effects of ROS scavengers on the plumbagin-induced augmentation of PhE-pretone (F, H).

|

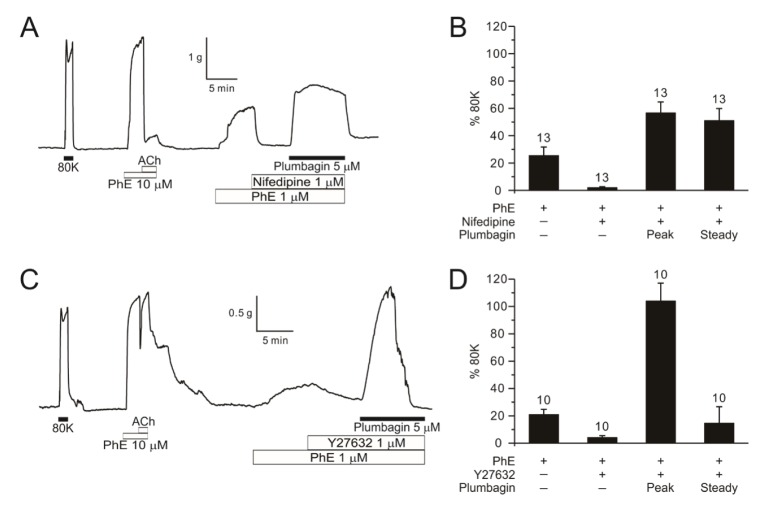

| Fig. 5Effects of calcium channel blocker and ROK inhibitor on plumbagin-contraction in PhE-treated DFA.A representative data of 1 µM nifedipine (calcium channel blocker) effect (n=13) before 5 µM plumbagin (A) and 1 µM Y27632 (Rho kinase inhibitor) effect (n=10) before 5 µM plumbagin in DFA (C). Summary shown as a bar graph (B, D).

|

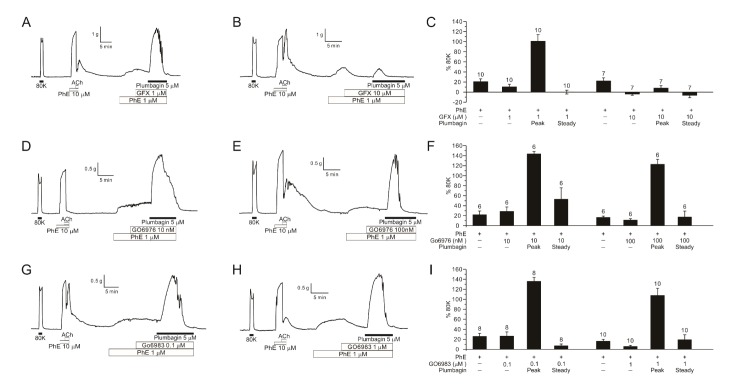

| Fig. 6Effects of PKC inhibitors on plumbagin-contraction in PhE-treated DFA.Representative traces of 1 µM (A, n=10) and 10 µM GFX (B, n=7) pre-treatment in DFAs, showing marked suppression of plumbagin-induced contraction by 10 µM GFX. Bar graphs of normalized contraction values assorted by the concentration of GFX (C). Representative traces of 10 nM (D, n=6) and 100 nM Go6976 (E, n=6) effects on plumbagin-induced contraction in PhE-treated DFA. Bar graphs of normalized contraction values assorted by the concentration of Go6976 (F). Representative traces of 0.1 µM (G, n=8) and 1 µM (H, n=10) Go6983 effects on plumbagin-induced contraction in PhE-treated DFA. Bar graphs of normalized contraction values assorted by the concentration of Go6983 (I). In the bar graphs, numbers of tested vessels are indicated above each bar.

|

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download