Abstract

Wnk kinase maintains cell volume, regulating various transporters such as sodium-chloride cotransporter, potassium-chloride cotransporter, and sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) through the phosphorylation of oxidative stress responsive kinase 1 (OSR1) and STE20/SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK). However, the activating mechanism of Wnk kinase in specific tissues and specific conditions is broadly unclear. In the present study, we used a human salivary gland (HSG) cell line as a model and showed that Ca2+ may have a role in regulating Wnk kinase in the HSG cell line. Through this study, we found that the HSG cell line expressed molecules participating in the WNK-OSR1-NKCC pathway, such as Wnk1, Wnk4, OSR1, SPAK, and NKCC1. The HSG cell line showed an intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) increase in response to hypotonic stimulation, and the response was synchronized with the phosphorylation of OSR1. Interestingly, when we inhibited the hypotonically induced [Ca2+]i increase with nonspecific Ca2+ channel blockers such as 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, gadolinium, and lanthanum, the phosphorylated OSR1 level was also diminished. Moreover, a cyclopiazonic acid-induced passive [Ca2+]i elevation was evoked by the phosphorylation of OSR1, and the amount of phosphorylated OSR1 decreased when the cells were treated with BAPTA, a Ca2+ chelator. Finally, through that process, NKCC1 activity also decreased to maintain the cell volume in the HSG cell line. These results indicate that Ca2+ may regulate the WNK-OSR1 pathway and NKCC1 activity in the HSG cell line. This is the first demonstration that indicates upstream Ca2+ regulation of the WNK-OSR1 pathway in intact cells.

Wnk, with no lysine, means that there is a lack of a conserved lysine residue in subcatalytic domain II, which is required for ATP binding [1]. Wnk kinases (WNKs) are serine/threonine protein kinases and are well conserved in many species from fungi to mammals [1]. Previous work by another group revealed that four types of WNKs are expressed in humans: Wnk1, Wnk2, Wnk3, and Wnk4 [2]. After the finding that mutations in Wnk1 and Wnk4 cause the disease pseudohypoaldosteronism type II (PHA II, OMIM no. 145260), many subsequent studies followed [3]. PHA II involves hypertension, with increased NaCl reabsorption and impaired K+ and H+ excretion [3]. Those clinical symptoms of PHA II indicate that WNKs perform roles in the kidney [4]. Consequently, early Wnk studies focused on transporters or channels located in the kidney and found that Wnk4 regulates the renal outer medullary potassium channel [5], the sodium-chloride cotransporter (NCC) [6,7], the sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter (NKCC) [6,7,8], and claudin [9,10] which is a component of tight junctions. Thereafter, it was found that activated Wnk1 phosphorylates oxidative stress responsive kinase 1 (OSR1) and STE20/SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) and that activated OSR1/SPAK phosphorylates the N-terminus of NKCC, which is required for activation [6,8]. WNK is activated via autophosphorylation and regulated by the presence of an autoinhibitory domain [11]. Moreover, the Wnk autoinhibitory domain is conserved in all of the WNKs [11], and the autoinhibitory domain of Wnk1 restrains not only the autophosphorylation of Wnk1 but also that of Wnk2 and Wnk4 [12].

Although the presence of autophosphorylation/autoinhibition was discovered early, the regulating mechanism of WNKs is still poorly understood [13,14,15]. Several mechanisms regulating WNKs have been revealed [13]. One is ubiquitination through scaffolding proteins such as CUL3, KLHL2, and KLHL3 [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Another regulating system is phosphorylation modulated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt (PIP3K/Akt) [23] and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 3 (ASK3) [24,25]. The activation of WNKs in low Cl- conditions is the most direct regulation of WNKs [13]. Although the presence of SPAK/OSR1 phosphorylation induced by low Cl- was revealed early [26], it remains a mystery how WNKs sense the low Cl-, and the possibility of there being another Cl- sensor that regulates WNKs still exists. Recently, the direct binding of Cl- to a catalytic domain of Wnk1 was revealed by crystallography [27]. Nonetheless, an upstream regulator of WNKs is still not enough to explain all of the regulatory machinery.

Ca2+ is a well-known second messenger that mediates various cell functions [28]. It is well known that hypotonicity induces the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ levels through the Ca2+ channels located in the plasma membrane. In addition, Ca2+-activated Cl- channels are well defined in the salivary glands. Therefore, we hypothesized that Ca2+ might regulate the WNK-OSR1 pathway, and we found that alterations of the intracellular Ca2+ level determined the phosphorylation of OSR1 and the activity of NKCC1 in a human salivary gland (HSG) cell line.

HSG cell line was a gift from Dr. Kyungpyo Park in Seoul National University. Rabbit polyclonal p-OSR1 antibody was purchased from Millipore (Cat#07-2273). Rabbit polyclonal OSR1 antibody was purchased from Cell signaling (#3729). Cyclopiazonic acid was from Enzo life science Farmingdale, NY, USA). 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate was from Tocris (Bristol, BS11 0QL, UK). Trypsin/EDTA, Fetal Bovine Serum, and 100X Antibiotic-Antimycotic was from Gibco (Carlsbad, CA, USA). BCECF-AM, BAPTA-AM, and Pluronic acid F-127 was from Life technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Fura2-AM was from Teflabs (Austin, TX, USA). NaCl, NH4Cl was from Duksan (Ansan, Gyeonggi-do, Korea). KCl, EGTA, Glucose, and HEPES was from Amresco (Solon, OH, USA). Collagenase P was from Roche (Indiana polis, IN, USA). All other chemicals include MgCl2, CaCl2, Trypsin inhibitor, sodium pyruvate, gadolinium, lanthanum, and ruthenium red was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

ICR mice were purchased from (KOATEC, Korea). All experiments were performed on adult male ICR mice (6-8 weeks of age) that were maintained on a 12h day/night cycle with normal mouse chow and water provided ad libitum. The animal studies were performed after receiving approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) in Yonsei University (IACUC approval no. 2014-0067). Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under CO2 anesthesia. The cells were prepared from the parotid gland and sub-mandibular gland of ICR mice by limited collagenase digestion as previously described [29]. Following isolation, the acinar cells were suspended in an extracellular physiologic salt solution (PSS), the composition of which was as follows (in mm): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 Glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with 5 N NaOH and to 310 mOsm with 5 M NaCl.

HSG cell-line was maintained with high-glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium with 10% FBS and 1X Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco, CA, USA) in 95% CO2, 5% O2, 37℃ incubator. Subculture was done with Trypsin/EDTA when cells are confluent. Cells that used in the calcium imaging and NKCC1 activity measurement were cultured on the 24×24 mm size of cover glass.

Total RNA was extracted from isolated pancreatic acinar cells using Trizol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RT-PCR was performed using a SuperScript III RT kit (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and oligo-dTs (Fermentas, MA, USA). For PCR analysis of the following primers were used:

hWnk1 (forward: 5'-AATCCAGTGCTTCCCAGACA-3', reverse: 5'-TCTGTTGGCTGCTCACTCGAGATT-3'), hWnk4 (forward: 5'-AGCTGCGTAAAGCAAGGGAATTGG-3', reverse: 5'-TTTGTCCCATCCCTTCTCCCACAT-3'), hOSR1 (forward: 5'-AGGTTCCAGTGGGCGTCTTCATAA-3', reverse: 5'-AGGCCAGCAGAAATGAGTTCCTGA-3'), hSPAK (forward: 5'-ATTCAAGCCATGAGTCAGTGCAGC-3', reverse: 5'-GCGCTGCTCCTGTTGCTAATTCAA-3'), hNKCC1 (forward: 5'-AAGCAGTCCTTGTTCCTATGGCCT-3', reverse: 5'-GCAATGCAGCCCACCAGTTAATGA-3'), hGAPDH (forward: 5'-CGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGTAT-3', reverse: 5'-AGCCTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAAGAC-3')

PCR reaction was performed using EmeraldAmp GT PCR Master Mix (Takara, Shiga, Japan). PCR condition was initiated by a 5 min incubation of the samples at 94℃, preceded by 30 (Wnk1, Wnk4), 35 (OSR1, SPAK, NKCC1, GAPDH) cycles of 30 sec at 94℃, 30 sec for annealing (Wnk1 57℃, Wnk4 60℃, OSR1 58℃, SPAK 59℃, NKCC 58℃, GAPDH 58℃), and 30 sec at 72℃. After 30 (Wnk1, Wnk4), 35 (OSR1, SPAK, NKCC1, GAPDH) cycles, samples were incubated for 10 min at 72℃ for complete extension. No reverse transcription control was performed using the same protocol, except for using reverse transcriptase.

Cultured on 24×24 mm coverglass, with density of 1.5×106 cells/ml with 48 h were loaded with 4 µM Fura-2/AM and 0.05% Pluronic acid F-127 for 30 min in PSS at room temperature. Fura-2/AM fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelengths of 340/380 nm, and emission was measured at 510 nm (ratio=F340/F380) using an imaging system (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). The emitted fluorescence was monitored using a CCD camera (CoolSNAP HQ, AZ, USA) attached to an inverted microscope. Fluorescence images were obtained at 2 sec intervals. All data were analyzed using the MetaFluor software (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA, USA).

Protein extracts were prepared from HSG cell-line and ICR salivary glands as follows. Cells were lysed in a buffer containing (in mm): 150 NaCl, 10 Tris (pH 7.8 with HCl), 1 EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, and a protease inhibitor mixture (2 Na3VO4, 10 NaF, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, and 10 µg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The samples were probed overnight with 1:2,000 dilutions of antibodies against p-OSR1, OSR1 at 4℃ and then separated by SDS-PAGE.

pHi was measured using pH sensitive fluorescent dye, BCECF-AM. Cells were loaded with 2.5 µM BCECF-AM in PSS for 30 min at room temperature. The fluorescence at excitation wavelength of 490 nm and 440 nm was recorded using a CCD camera (CoolSNAP HQ, AZ, USA). Fluorescence images were obtained at 2 sec intervals. All data were analyzed using the MetaFluor software (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA, USA).

Na+-K+-2Cl- cotransporter (NKCC) activity was measured from the pHi decrease induced by the intracellular uptake of NH4+ using the methods of Evans and Turner [30] with modifications. Adding NH4Cl 20 mM in the extracellular solution induce robust increase of pHi due to diffusion of NH3 (Fig. 4E). Thereafter, pHi is getting decreased by influx of NH4+, because NH4+ acts as a surrogate of K+ in the NKCC. To discriminate only the NKCC activity, 100 µM bumetanide applied. Slope inclination was measured from 1 min to 3 min after solution change.

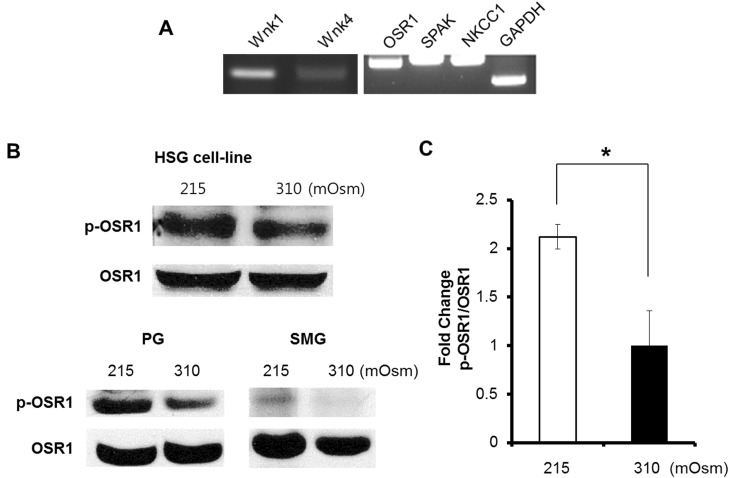

The expression of WNKs in the HSG cell line was previously unknown. Therefore, we first investigated WNK and its substrates, OSR1 and SPAK. Reverse-transcription PCR was performed, and we confirmed the mRNA expression of Wnk1, Wnk4, OSR1, SPAK, and NKCC1 in an HSG cell line (Fig. 1A). The Wnk4 expression level was lower than the Wnk1 expression level (Fig. 1A). The next step was the measurement of OSR1 phosphorylation at serine 325 by immunoblotting. The phosphorylation of OSR1 at serine 325 to form p-OSR1, the activated form of OSR1, is mediated by WNK. Hence, the elevation of p-OSR1 levels is considered indirect evidence showing the activation of WNK, because OSR1 is a main substrate of WNK. We observed an increase in the p-OSR1 level after 15 min of hypotonic (215 mOsm) stimulation at 37℃ (Fig. 1B, upper panel). The hypotonic stimulation was induced using a hypotonic solution (HS) that reduced only the NaCl content of a physiologic salt solution (PSS). We observed a p-OSR1 increase in isolated parotid gland acini and also in submandibular gland acini from an ICR mouse (Fig. 1B. lower panel). These data suggest that the HSG cell line can imitate hypotonically induced OSR1 activation.

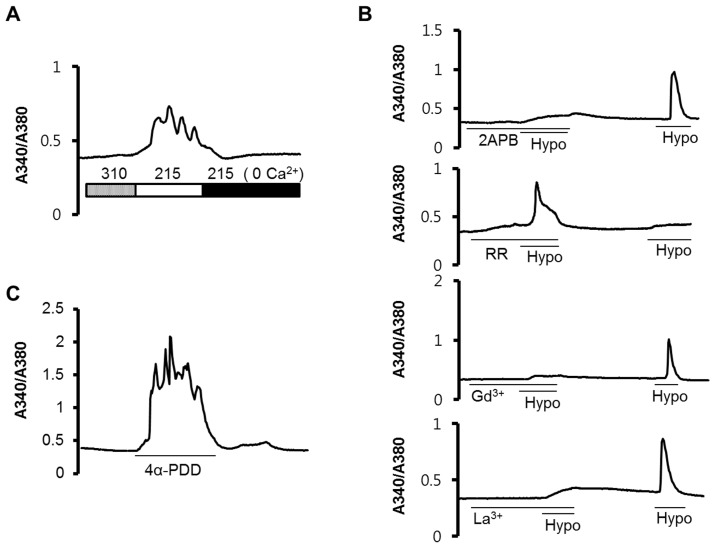

Extracellular HS treatment induced an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), and was abolished with the depletion of Ca2+ ions in the extracellular solution (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the increased Ca2+ signal originated from the outside of the cell. To define how the Ca2+ influx was mediated by extracellular Ca2+ ions, we used 10 µM ruthenium red (RR), 100 µM 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2APB), 10 µM gadolinium (Gd3+), and 10 µM lanthanum (La3+) as blockers. After 5 min of pre-incubation with 2APB, Gd3+, and La3+, hypotonic stimulation did not evoke an elevation in the [Ca2+]i. However, RR could not inhibit the [Ca2+]i increase (Fig. 2B). When we added 10 µM 4α-phorbol 12, 13-didecanoate (4α-PDD) to the isotonic PSS (310 mOsm), we observed similar patterns of [Ca2+]i increase (Fig. 2C).

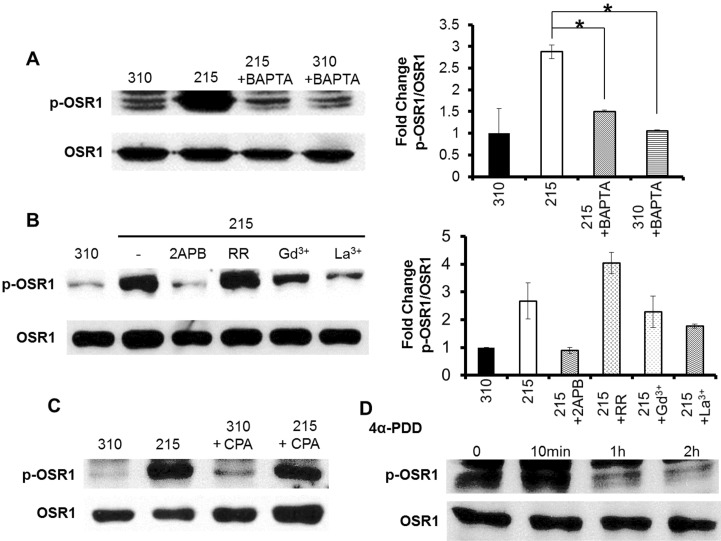

BAPTA is a high-affinity Ca2+ chelator that acts rapidly. When we loaded 25 µM BAPTA-AM, which is an acetomethoxy ester conjugate of BAPTA, 20 min prior to the hypotonic stimulation, the p-OSR1 level was reduced compared with that in a control after 10 min of hypo-osmotic stress (Fig. 3A, left panel). The fold change of the p-OSR1/total OSR1 intensity was 2.88±0.15 in 215 mOsm, 1.51±0.02 in 215 mOsm+BAPTA, and 1.06±0.01 in 310 mOsm+BAPTA (Fig. 3A, right panel). This result indicates that p-OSR1 may be regulated by upstream Ca2+ ions. The 4α-PDD-induced p-OSR1 level was also increased 10 min after treatment and diminished less than that in the control after 1 h (Fig. 3C). In agreement with the Ca2+ signaling pattern, the p-OSR1 level was reduced following a 20 min pre-incubation with the blockers 2APB, Gd3+, and La3+ (Fig. 3B). RR could not inhibit the hypotonic-induced [Ca2+]i increase in the HSG cell line (Fig. 2B, second panel from the top), and the p-OSR1 level was increased in the RR pre-incubation only (Fig. 3B). The Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) induced by 25 µM cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) could also elevate the p-OSR1 level (Fig. 3D).

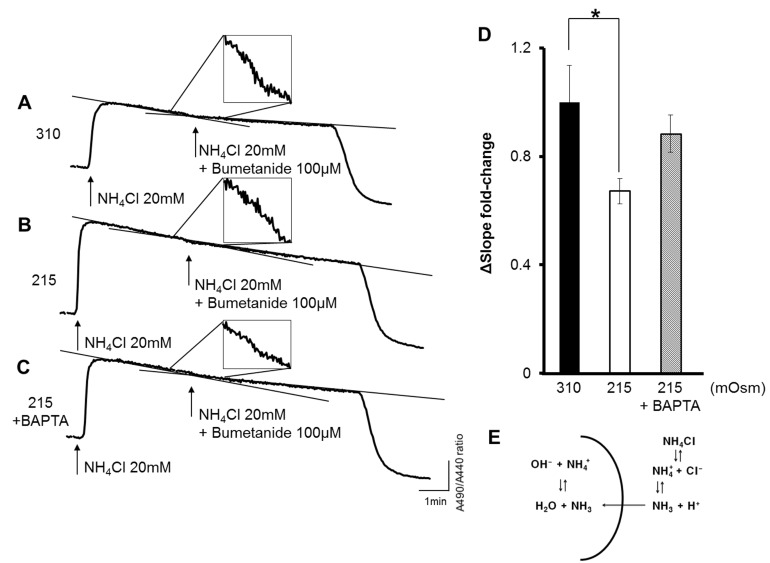

The activation of OSR1 could affect the various transporters in the plasma membrane, such as the NCC, the K+-Cl- cotransporter (KCC), and the NKCC. In the present study, we measured NKCC activity using pH changes in the HSG cells. The traces in Fig. 4A-C show the BCECF ratio of emitting wave intensity in the excitation wave-lengths 490 nm and 440 nm. Thus, the value of the BCECF ratio indicates the intracellular pH (pHi). Fig. 4E shows the scheme of the NH4Cl treatment. When 20 mm NH4Cl was added to the extracellular solution, with the substitution of NaCl to maintain the osmolarity, the influx of NH3 cause pH increase. After that, through NKCC1 activity, which carries NH4+ as a surrogate of K+, the pH in the solution acidified. Bumetanide (100 µM) can inhibit NKCC activity. Therefore, the difference in the slope inclination between the NH4Cl treatment and the bumetanide treatment was assessed to measure the NKCC1 activity by quantifying the acidification rate. The greatest slope change was with 100 µM bumetanide in the isotonic solution (310 mOsm; Fig. 4A). After pre-incubation in HS (215 mOsm) for 5 min, the fold change in the slope was 0.67±0.05 (Fig. 4B), which was statistically significant (Fig. 4D). After pre-incubation with 25 µM BAPTA-AM in HS, the decreased fold change in the slope was restored (Fig. 4C, D).

In the present study, we found that the phosphorylation of OSR1 is regulated by the [Ca2+]i. This was a unique finding of our study. In other articles, it was shown by using a kinase assay that Wnk4 kinase activity increased depending on the Ca2+ concentration in vitro, and that effect was diminished by the substitution of acidic amino acid residues such as E562 and D564 in Wnk4 [31]. Tacrolimus, which is a calcineurin inhibitor, induced Wnk3, Wnk4, and SPAK expression in mouse kidney [32]. Those previous studies support our findings that p-OSR1 is regulated by the [Ca2+]i.

The other issue in this study is that a source of increased Ca2+ triggered the phosphorylation of OSR1. When we removed the external Ca2+ from the hypotonic solution (Fig. 2A), the [Ca2+]i was reduced to the baseline. That result shows that the increased [Ca2+]i in the HSG cell line originated from the influx of external calcium. 2APB, an inhibitor of Ca2+ channels [33,34], was used to block the influx of Ca2+. 2APB also inhibits the IP3 induced Ca2+ increase. However, even though 2APB acts as an inhibitor of either IP3 induced Ca2+ increase or nonselective cation channel, the outcome of 2APB treatment is an inhibition of [Ca2+]i increase. In the results pretreatment with 2APB inhibited the elevation of the [Ca2+]i and reduced the level of p-OSR1 induced by hypotonic stress in the HSG cell line (Fig. 2B, 3B). Furthermore, nonselective cation channel blockers, like Gd3+ and La3+, also inhibited the [Ca2+]i and the p-OSR1 level under hypotonic stress in the HSG cell line (Fig. 2B, 3B). Those results indicate external Ca2+ influx mediated by Ca2+ channels sensitive to 2APB, Gd3+, and La3+ in the HSG cell line. Interestingly, treatment with 4α-PDD, which is a selective activator of TRPV4, displayed Ca2+ signaling patterns similar to those displayed by hypotonic stimulation [35,36]; TRPV4 is a well-known Ca2+ permeable channel activated by hypotonic stress [37]. Thus, a TRPV4-induced [Ca2+]i appears to be one potent channel that mediates the OSR1 pathway in the HSG cell line, but that hypothesis requires more experiments to be confirmed. Likewise, another TRP channels, such as TRPC3, and TRPM4 also involved hypotonicity stimulated Ca2+ influx in the HSG cell line, but we have not included in this paper. It was unexpected that RR could not inhibit the [Ca2+]i and the p-OSR1 level. That result suggests that RR-resistant Ca2+ channels play a role in the HSG cell line. However, to solve that remaining question about RR, another investigation is required.

The next question is whether the Ca2+ performed as an upstream regulator or as a downstream messenger of OSR1 phosphorylation. Because BAPTA is a rapid and high-affinity chelator of Ca2+, it is regarded as a highly efficient chelator that blocks the action of Ca2+ in the cell [38]. When the [Ca2+]i was chelated by BAPTA during the hypotonic stimulation of the HSG cell line, the p-OSR1 level was decreased (Fig. 3A). That suggests that Ca2+ is an upstream regulator of p-OSR1. Ca2+ is more important than the mechanical membrane stretching induced by the HS. It is inferred from the facts that the [Ca2+]i increases with 4α-PDD (Fig. 3D), and CPA (Fig. 3C) also resulted in increased p-OSR1 levels. However, the CPA induced less p-OSR1 than did the hypotonic stimulation. That could be explained by the localization of the WNKs near the plasma membrane [1].

Although, Ca2+ regulates OSR1 through phosphorylation, it is still unclear whether OSR1 is directly or indirectly regulated by the WNKs. Ca2+ was required to show the kinase activity of Wnk4. In the intact cell, however, remaining kinase activity appeared at very low Ca2+ concentrations, below 1 nM [31]. Moreover, it is well known that WNKs exhibit autoinhibition and autophosphorylation [11,12], and role of low Cl- in the activation of WNKs was revealed by crystallography [27]. Furthermore, it is well known that Ca2+-activated Cl- channels, like TMEM16A, are expressed in the apical membranes of salivary gland acinar cells [39]. Therefore, we assumed that TMEM16A activated by an elevated [Ca2+]i contributes to the local depletion of Cl- at the microdomain level, and that the depletion of Cl- leads to the activation of the WNK-OSR1 pathway. However, more investigations will be required to test that model.

The popular effectors of activated OSR1 are the NCC, the KCC, and the NKCC [13,14,15]. Furthermore, the NKCC is the essential molecule that maintains Cl- homeostasis in salivary gland acinar cells [39]. For that reason, we investigated the alteration of NKCC activity in the HSG cell line (Fig. 4). After hypotonic stimulation, NKCC activity was reduced in the HSG cell line and was recapitulated by chelating Ca2+ through BAPTA pretreatment (Fig. 4D). It is still controversial whether activated OSR1 contributes to the activation or to the inactivation of NKCC, depending on the cell type [24,40]. In terms of volume homeostasis, we think that the inhibition of NKCC requires cells to decrease the intracellular ion osmolarity to maintain the cell volume.

In conclusion, we found that Ca2+ regulates the WNK-OSR1-NKCC pathway. This is the first study to demonstrate the Ca2+-mediated WNK-OSR1-NKCC pathway in an intact HSG cell line. We hope that these results will help to clarify the regulatory mechanism of the WNK-OSR1 pathway and further our understanding of the mechanism of salivary secretion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2013R1A1A2006269).

References

1. Xu B, English JM, Wilsbacher JL, Stippec S, Goldsmith EJ, Cobb MH. WNK1, a novel mammalian serine/threonine protein kinase lacking the catalytic lysine in subdomain II. J Biol Chem. 2000; 275:16795–16801. PMID: 10828064.

2. Verissimo F, Jordan P. WNK kinases, a novel protein kinase subfamily in multi-cellular organisms. Oncogene. 2001; 20:5562–5569. PMID: 11571656.

3. Wilson FH, Disse-Nicodeme S, Choate KA, Ishikawa K, Nelson-Williams C, Desitter I, Gunel M, Milford DV, Lipkin GW, Achard JM, Feely MP, Dussol B, Berland Y, Unwin RJ, Mayan H, Simon DB, Farfel Z, Jeunemaitre X, Lifton RP. Human hypertension caused by mutations in WNK kinases. Science. 2001; 293:1107–1112. PMID: 11498583.

4. Gamba G. Role of WNK kinases in regulating tubular salt and potassium transport and in the development of hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005; 288:F245–F252. PMID: 15637347.

5. Kahle KT, Wilson FH, Leng Q, Lalioti MD, O'Connell AD, Dong K, Rapson AK, MacGregor GG, Giebisch G, Hebert SC, Lifton RP. WNK4 regulates the balance between renal NaCl reabsorption and K+ secretion. Nat Genet. 2003; 35:372–376. PMID: 14608358.

6. Vitari AC, Deak M, Morrice NA, Alessi DR. The WNK1 and WNK4 protein kinases that are mutated in Gordon's hypertension syndrome phosphorylate and activate SPAK and OSR1 protein kinases. Biochem J. 2005; 391:17–24. PMID: 16083423.

7. Rinehart J, Kahle KT, de Los, Vazquez N, Meade P, Wilson FH, Hebert SC, Gimenez I, Gamba G, Lifton RP. WNK3 kinase is a positive regulator of NKCC2 and NCC, renal cation-Cl-cotransporters required for normal blood pressure homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005; 102:16777–16782. PMID: 16275913.

8. Moriguchi T, Urushiyama S, Hisamoto N, Iemura S, Uchida S, Natsume T, Matsumoto K, Shibuya H. WNK1 regulates phosphorylation of cation-chloride-coupled cotransporters via the STE20-related kinases, SPAK and OSR1. J Biol Chem. 2005; 280:42685–42693. PMID: 16263722.

9. Kahle KT, Macgregor GG, Wilson FH, Van Hoek AN, Brown D, Ardito T, Kashgarian M, Giebisch G, Hebert SC, Boulpaep EL, Lifton RP. Paracellular Cl- permeability is regulated by WNK4 kinase: insight into normal physiology and hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004; 101:14877–14882. PMID: 15465913.

10. Yamauchi K, Rai T, Kobayashi K, Sohara E, Suzuki T, Itoh T, Suda S, Hayama A, Sasaki S, Uchida S. Disease-causing mutant WNK4 increases paracellular chloride permeability and phosphorylates claudins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004; 101:4690–4694. PMID: 15070779.

11. Xu BE, Min X, Stippec S, Lee BH, Goldsmith EJ, Cobb MH. Regulation of WNK1 by an auto-inhibitory domain and autophosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2002; 277:48456–48462. PMID: 12374799.

12. Lenertz LY, Lee BH, Min X, Xu BE, Wedin K, Earnest S, Goldsmith EJ, Cobb MH. Properties of WNK1 and implications for other family members. J Biol Chem. 2005; 280:26653–26658. PMID: 15883153.

13. Alessi DR, Zhang J, Khanna A, Hochdorfer T, Shang Y, Kahle KT. The WNK-SPAK/OSR1 pathway: master regulator of cation-chloride cotransporters. Sci Signal. 2014; 7:re3. PMID: 25028718.

14. Arroyo JP, Kahle KT, Gamba G. The SLC12 family of electroneutral cation-coupled chloride cotransporters. Mol Aspects Med. 2013; 34:288–298. PMID: 23506871.

15. Kahle KT, Rinehart J, Lifton RP. Phosphoregulation of the Na-K-2Cl and K-Cl cotransporters by the WNK kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010; 1802:1150–1158. PMID: 20637866.

16. Schumacher FR, Sorrell FJ, Alessi DR, Bullock AN, Kurz T. Structural and biochemical characterization of the KLHL3-WNK kinase interaction important in blood pressure regulation. Biochem J. 2014; 460:237–246. PMID: 24641320.

17. McCormick JA, Yang CL, Zhang C, Davidge B, Blankenstein KI, Terker AS, Yarbrough B, Meermeier NP, Park HJ, McCully B, West M, Borschewski A, Himmerkus N, Bleich M, Bachmann S, Mutig K, Argaiz ER, Gamba G, Singer JD, Ellison DH. Hyperkalemic hypertension-associated cullin 3 promotes WNK signaling by degrading KLHL3. J Clin Invest. 2014; 124:4723–4736. PMID: 25250572.

18. Wakabayashi M, Mori T, Isobe K, Sohara E, Susa K, Araki Y, Chiga M, Kikuchi E, Nomura N, Mori Y, Matsuo H, Murata T, Nomura S, Asano T, Kawaguchi H, Nonoyama S, Rai T, Sasaki S, Uchida S. Impaired KLHL3-mediated ubiquitination of WNK4 causes human hypertension. Cell Rep. 2013; 3:858–868. PMID: 23453970.

19. Takahashi D, Mori T, Wakabayashi M, Mori Y, Susa K, Zeniya M, Sohara E, Rai T, Sasaki S, Uchida S. KLHL2 interacts with and ubiquitinates WNK kinases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013; 437:457–462. PMID: 23838290.

20. Ohta A, Schumacher FR, Mehellou Y, Johnson C, Knebel A, Macartney TJ, Wood NT, Alessi DR, Kurz T. The CUL3-KLHL3 E3 ligase complex mutated in Gordon's hypertension syndrome interacts with and ubiquitylates WNK isoforms: disease-causing mutations in KLHL3 and WNK4 disrupt interaction. Biochem J. 2013; 451:111–122. PMID: 23387299.

21. Mori Y, Wakabayashi M, Mori T, Araki Y, Sohara E, Rai T, Sasaki S, Uchida S. Decrease of WNK4 ubiquitination by disease-causing mutations of KLHL3 through different molecular mechanisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013; 439:30–34. PMID: 23962426.

22. Hossain Khan MZ, Sohara E, Ohta A, Chiga M, Inoue Y, Isobe K, Wakabayashi M, Oi K, Rai T, Sasaki S, Uchida S. Phosphorylation of Na-Cl cotransporter by OSR1 and SPAK kinases regulates its ubiquitination. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012; 425:456–461. PMID: 22846565.

23. Nishida H, Sohara E, Nomura N, Chiga M, Alessi DR, Rai T, Sasaki S, Uchida S. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway activates the WNK-OSR1/SPAK-NCC phosphorylation cascade in hyperinsulinemic db/db mice. Hypertension. 2012; 60:981–990. PMID: 22949526.

24. Naguro I, Umeda T, Kobayashi Y, Maruyama J, Hattori K, Shimizu Y, Kataoka K, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Uchida S, Vandewalle A, Noguchi T, Nishitoh H, Matsuzawa A, Takeda K, Ichijo H. ASK3 responds to osmotic stress and regulates blood pressure by suppressing WNK1-SPAK/OSR1 signaling in the kidney. Nat Commun. 2012; 3:1285. PMID: 23250415.

25. Kaji T, Yoshida S, Kawai K, Fuchigami Y, Watanabe W, Kubodera H, Kishimoto T. ASK3, a novel member of the apoptosis signal-regulating kinase family, is essential for stress-induced cell death in HeLa cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010; 395:213–218. PMID: 20362554.

26. Dowd BF, Forbush B. PASK (proline-alanine-rich STE20-related kinase), a regulatory kinase of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC1). J Biol Chem. 2003; 278:27347–27353. PMID: 12740379.

27. Piala AT, Moon TM, Akella R, He H, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. Chloride sensing by WNK1 involves inhibition of autophosphorylation. Sci Signal. 2014; 7:ra41. PMID: 24803536.

28. Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003; 4:517–529. PMID: 12838335.

29. Park S, Lee SI, Shin DM. Role of regulators of g-protein signaling 4 in ca signaling in mouse pancreatic acinar cells. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011; 15:383–388. PMID: 22359476.

30. Evans RL, Turner RJ. Upregulation of Na(+)-K(+)-2Cl- cotransporter activity in rat parotid acinar cells by muscarinic stimulation. J Physiol. 1997; 499:351–359. PMID: 9080365.

31. Na T, Wu G, Peng JB. Disease-causing mutations in the acidic motif of WNK4 impair the sensitivity of WNK4 kinase to calcium ions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012; 419:293–298. PMID: 22342722.

32. Hoorn EJ, Walsh SB, McCormick JA, Furstenberg A, Yang CL, Roeschel T, Paliege A, Howie AJ, Conley J, Bachmann S, Unwin RJ, Ellison DH. The calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus activates the renal sodium chloride cotransporter to cause hypertension. Nat Med. 2011; 17:1304–1309. PMID: 21963515.

33. Diver JM, Sage SO, Rosado JA. The inositol trisphosphate receptor antagonist 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate (2-APB) blocks Ca2+ entry channels in human platelets: cautions for its use in studying Ca2+ influx. Cell Calcium. 2001; 30:323–329. PMID: 11733938.

34. Bootman MD, Collins TJ, Mackenzie L, Roderick HL, Berridge MJ, Peppiatt CM. 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) is a reliable blocker of store-operated Ca2+ entry but an inconsistent inhibitor of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release. FASEB J. 2002; 16:1145–1150. PMID: 12153982.

35. Hatano N, Itoh Y, Muraki K. Cardiac fibroblasts have functional TRPV4 activated by 4alpha-phorbol 12,13-didecanoate. Life Sci. 2009; 85:808–814. PMID: 19879881.

36. Kim KS, Shin DH, Nam JH, Park KS, Zhang YH, Kim WK, Kim SJ. Functional expression of trpv4 cation channels in human mast cell line (HMC-1). Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010; 14:419–425. PMID: 21311684.

37. Nilius B, Vriens J, Prenen J, Droogmans G, Voets T. TRPV4 calcium entry channel: a paradigm for gating diversity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004; 286:C195–C205. PMID: 14707014.

38. Kline D, Kline JT. Repetitive calcium transients and the role of calcium in exocytosis and cell cycle activation in the mouse egg. Dev Biol. 1992; 149:80–89. PMID: 1728596.

39. Melvin JE, Yule D, Shuttleworth T, Begenisich T. Regulation of fluid and electrolyte secretion in salivary gland acinar cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005; 67:445–469. PMID: 15709965.

40. Wu Y, Schellinger JN, Huang CL, Rodan AR. Hypotonicity stimulates potassium flux through the WNK-SPAK/OSR1 kinase cascade and the Ncc69 sodium-potassium-2-chloride cotransporter in the Drosophila renal tubule. J Biol Chem. 2014; 289:26131–26142. PMID: 25086033.

Fig. 1

Phosphorylated OSR1 induced by hypotonicity and mRNA expression in a HSG cell line and phosphorylation of OSR1 in an isolated salivary gland acinar cell. (A) RT-PCR confirmed the expression of Wnk1, Wnk4, OSR1, SPAK, and NKCC1 at mRNA level. GAPDH expression was used as a control. (B) A hypotonic solution (215 mOsm) induced an increase in phosphorylated OSR1 (p-OSR1) in the HSG cell line (upper panel) and p-OSR1 in the parotid gland (PG) and submandibular gland (SMG) from ICR mice (lower panel). (C) The p-OSR1 level in the HSG cell line was normalized with the total OSR1 (right panel). HSG cell line n=3, mouse salivary gland acinar cell n=1, *p<0.05.

Fig. 2

Hypotonic stress-induced intracellular Ca2+ increases. The intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) was shown as the Fura2 intensity ratio of A340/A380. (A) A [Ca2+]i increase was observed when the cells were treated with a hypotonic solution, and the increased [Ca2+]i was diminished after the removal of extracellular Ca2+. (B) Pretreatment with 2APB, Gd3+, and La3+ reduced the [Ca2+]i induced by the hypotonic stimulation, and after washout of the blockers, the hypotonic stress-induced [Ca2+]i was recapitulated. (C) 4α-PDD evoked an increase in the [Ca2+]i. All the graphs show a representative trace, n=20~30 cells.

Fig. 3

Phosphorylation of OSR1 with various Ca2+ signaling-related drugs. (A) Pretreatment with 25 µM BAPTA/AM for 20 min followed by treatment with a hypotonic solution (215 mOsm) for 10 min. The fold change of the p-OSR1/OSR1 between control and BAPTA-loaded cells was statistically significant in the hypotonic stimulation. (B) Before hypotonic stimulation, each of the blockers was incubated for 20 min at 37℃, and then the cells were treated with the hypotonic solution for 10 min. 2APB 100 µM, RR 10 µM, Gd3+ 10 µM, and La3+ 10 µM was applied. (C, D) Up-regulated p-OSR1 was observed with both 25 µM CPA and 10 µM 4α-PDD applied in an isotonic solution (310 mOsm) *p<0.05. n=3 each.

Fig. 4

Down-regulation of NKCC activity is induced by hypotonic stress in a HSG cell line. Intracellular pH indicated by the BCECF signal ratio. (A) A decline in the rate after bumetanide (100 µM) treatment was decreased in an isotonic solution (310 mOsm); however, (B) after hypotonic stimulation (215 mOsm), the degree of the decline in the rate was reduced. (C) Chelating [Ca2+]i with 25 µM BAPTA-AM treatment restored the bumetanide-sensitive modification of the BCECF ratio. (A~C) The narrow black line represents a trend line indicating the slope of the pH declination. The alteration of the slope by treatment by 100 µM bumetanide is emphasized in the box. (D) The shifting slope of the declination was expressed by the fold change. (E) Schematic diagram that shows role of NH4Cl in the intracellular pH modification. All the traces are representative graphs, with n=25~35 cells in each experiment. *p<0.05.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download