Abstract

Females are more often affected by constipation than males, especially during pregnancy, which is related to the menstrual cycle. Although still controversial, alterations of progesterone and estrogen may be responsible. Therefore, this study was conducted in order to determine whether the female sex steroid hormone itself is responsible for development of constipation in both female and male mice. Administration of estrogen resulted in a decrease in weight of accumulated feces on days 2, 3, 4, and 5 in male mice and on day 5 in female mice, compared with the control group, but progesterone administration did not. Administration of estrogen resulted in a decrease in gastrointestinal movement, compared to normal; however, no significant change was observed by administration of progesterone. In conclusion, estrogen, rather than progesterone, may be a detrimental factor of constipation via decreased bowel movement in mice.

Go to :

Constipation refers to bowel movements that are infrequent or difficult passage of stools due to colonic slow transit, and is a common cause of painful defecation and fecal impaction [1]. Causes of colonic slow transit include diet, hormones, side effects of medications, and heavy metal toxicity. Its incidence ranges from 2% to 30% in the general population [2,3], and females are more often affected than males [4]. Gender differences in hormone concentration could affect the gastrointestinal transit time. An association of constipation or slow colonic transit time with pregnancy [5-7] and menstrual cycle [8,9] has been reported. Progesterone has been the hormonal explication for many gastrointestinal symptoms that occur in pregnancy, including intestinal constipation [5], and is the main hormone of the luteal stage, compared with other phases of the menstrual cycle [10]. Some studies have reported an increase in constipation in females in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle [9], however, others have suggested that it is not affected by the luteal phase [11], and the same in both genders of colonic transit time [12,13]. Estrogen is produced primarily by the ovaries, and during pregnancy. Estrogen levels vary throughout the menstrual cycle, with the levels highest occurring near the end of the follicular phase just before ovulation.

Therefore, this study was conducted in order to determine of whether the female sex steroid hormone itself is responsible for development of constipation in both female and male mice.

Go to :

Specific pathogen-free male and female ICR mice (~10 weeks old) were purchased from Samtako, Inc. (Osan, Korea). Three animals were housed in a cage and fed with tap water and mouse chow diet (Nestle Purina PetCare Korea, Ltd., Seoul, Korea) for five days.

Mice (n=9 for each group) were randomly divided into three groups for the experiment on the effect of female sex steroid hormones on constipation in male or female mice. The first group, as the normal control group, was fed the chow diet only, and the second and third groups received daily oral administration of estrogen (β-estradiol, Sigma, St. Louis) 0.4 mg/kg or progesterone (Progynova, Schering SA, France) 1 mg/kg of body weight in 20 µl of corn oil for five days.

To test the effect of female sex steroid hormones on gastrointestinal function, the animals were fasted for one day and as much as 1 ml/100 g of body weight of 10% barium sulfate solution was administered directly into the stomach. After 30 min, mice were anesthetized with urethane and the moving distance of barium sulfate from the duodenal sphincter to the large intestine was measured.

Feces were collected and weighed daily. Dry weight of feces was measured from four days drying in the oven at 80℃.

Values are expressed as mean±SE. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for multiple comparisons. When ANOVA showed significant differences, post-hoc analysis was performed using the Newman-Keuls multiple range test by SPSS.

This study protocol was approved by the institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of animals were followed, and this research was approved by Animal Care and Use Committee of Yeungnam University.

Go to :

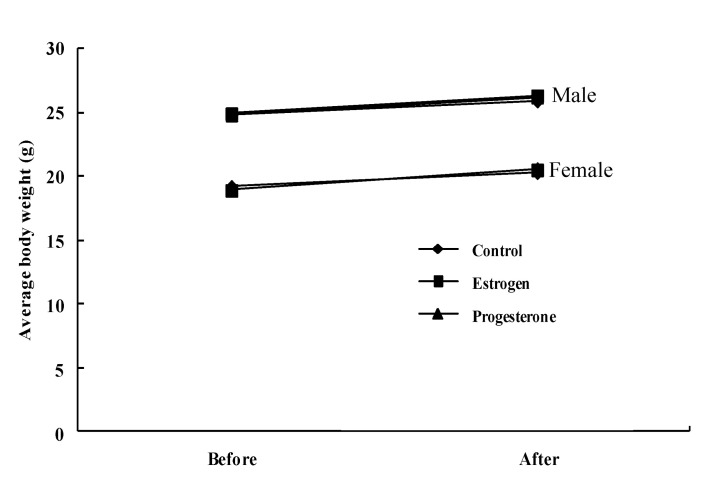

The body weight (g) of mice did not differ significantly among groups after sex steroid hormones administration for 5 days in both male (24.8±1.5, 24.9±1.6, and 24.8±1.6 of control, estrogen, and progesterone mice before hormone administration, respectively, and 25.9±1.7, 26.3±2.1, and 26.2±2.0, of control, estrogen, and progesterone mice after hormone administration, respectively) and female mice (19.2±1.3, 18.9±1.3, and 19.0±1.4 of control, estrogen, and progesterone mice before hormone administration, respectively, and 20.3±1.6, 20.5±1.7, and 20.6±1.7 of control, estrogen, and progesterone mice after hormone administration, respectively) (Fig. 1).

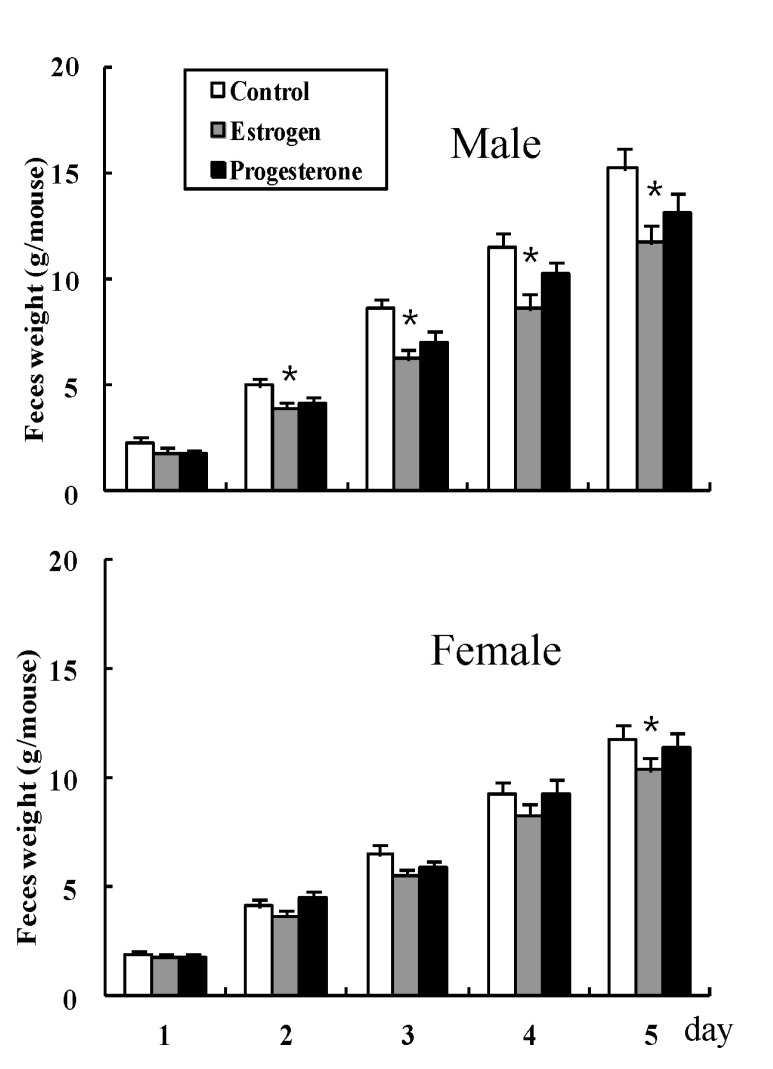

The weights of accumulated feces in male mice were 2.3±0.22, 5.0±0.35, 8.6±0.44, 11.5±0.62, and 15.2±0.93 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) in the normal control mice group, respectively, 1.8±0.22, 3.9±0.32, 6.2±0.44, 8.6±0.65, and 11.7±0.78 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) for estrogen administered mice, respectively, and 1.7±0.17, 4.1±0.29, 7.0±0.52, 10.2±0.62, and 13.1±0.88 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) for progesterone administered mice, respectively. The accumulated weights of feces in female mice were 1.9±0.16, 4.1±0.27, 6.5±0.39, 9.3±0.53, and 11.8±0.91 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) in the normal control mice group, respectively, 1.8±0.20, 3.7±0.28, 5.5±0.35, 8.3±0.54, and 10.4±0.83 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) for estrogen administered mice, respectively, and 1.8±0.18, 4.5±0.28, 5.8±0.38, 9.3±0.61, and 11.4±0.84 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) for progesterone administered mice, respectively (Fig. 2). Administration of estrogen resulted in a decrease in weight of accumulated feces on days 2, 3, 4, and 5 in male mice and day 5 in female mice, compared with the control group, but administration of progesterone did not (Fig. 2).

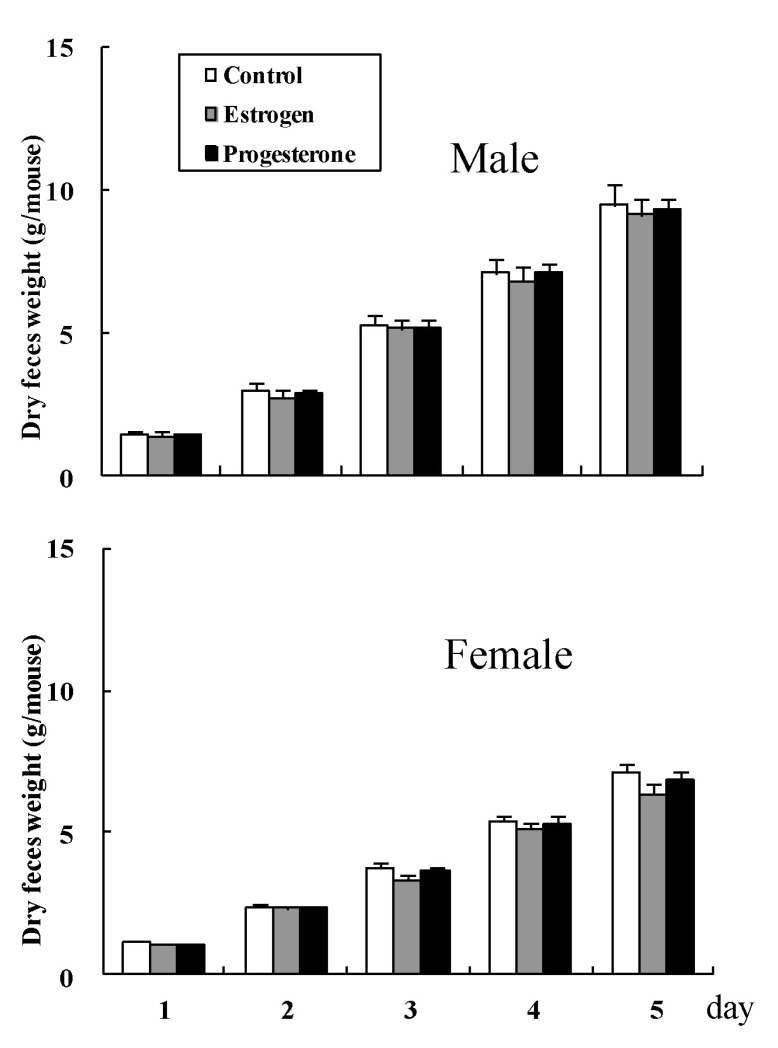

The accumulated dry weight (g) of feces did not differ significantly among groups in both male (1.4±0.06, 3.0±0.11, 5.3±0.25, 7.1±0.32, and 9.5±0.37 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) for normal control mice, respectively, 1.4±0.06, 2.7±0.10, 5.1±0.28, 6.8±0.25, and 9.1±0.32 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) for estrogen administered mice, respectively, and 1.4±0.05, 2.9±0.10, 5.2±0.31, 7.1±0.30, and 9.3±0.35 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) for progesterone administered mice, respectively), and female mice (1.1±0.04, 2.4±0.08, 3.8±0.21, 5.4±0.24, and 7.1±0.29 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) for normal control mice, respectively, 1.1±0.04, 2.3±0.08, 3.3±0.18, 5.1±0.23, and 6.4±0.31 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) for estrogen administered mice, respectively, and 1.1±0.05, 2.3±0.07, 3.6±0.19, 5.3±0.28, and 6.8±0.32 on days 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (g) for progesterone administered mice, respectively) (Fig. 3).

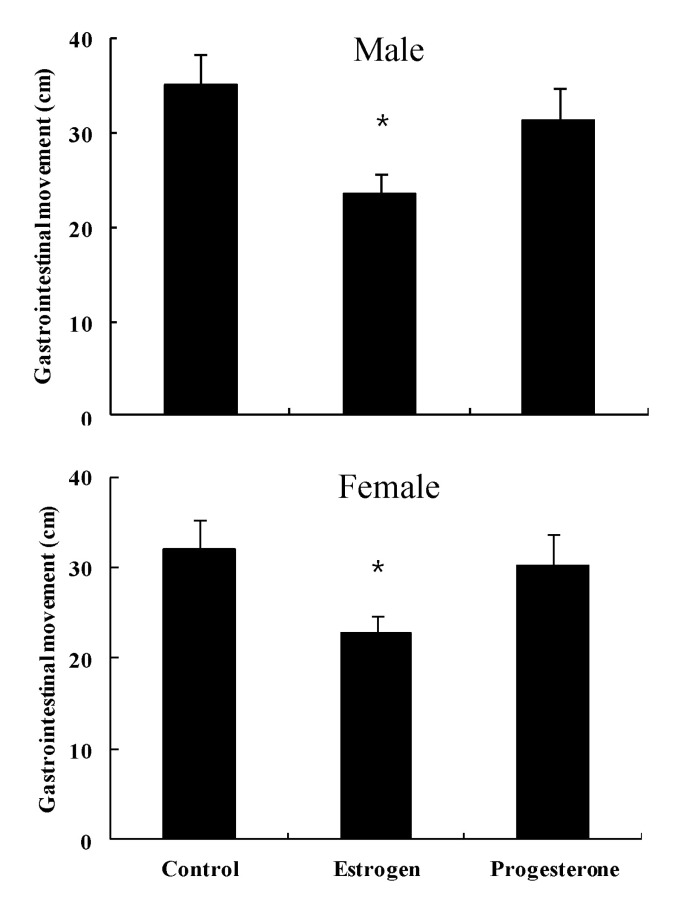

Length (cm) of barium transfer in normal control male mice was 35.2±3.3, and showed a decrease to 23.5±2.1 by administration of estrogen, but with no significant change (31.4±3.5) by administration of progesterone (Fig. 4). Length (cm) of barium transfer in normal control female mice was 33.1±3.1, and showed a decrease to 22.7±2.8 by administration of estrogen, but with no significant change (30.3±3.2) by administration of progesterone (Fig. 4).

Go to :

Constipation is a very common clinical problem [14] which may be associated with slow intestinal movement [15]. Women have a higher incidence of constipation than men, particularly in younger individuals [16]. The higher incidence is even more pronounced in female patients with slow transit constipation [17]. Ovarian hormones influence gastrointestinal function because estrogen receptors have been found in the gastric and small intestinal mucosa [18]. At the tissue level, female sex steroid hormones inhibit muscle contractility in a variety of sites, including lower esophageal sphincter [19], and colon [20]. Thus, alterations of progesterone and estrogen may be responsible. Although the association of female sex steroid hormones and constipation has been studied, it is still not clear. Incidence of constipation in females showed an increase [9] or did not change [11] in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. No significant difference in colonic transit time was observed between males and females [12]. The aim of this study was to clarify the effect of female sex steroid hormones on constipation. Our results showed that administration of estrogen induced constipation via a decrease in bowel movement in both male and female mice, but progesterone did not. This result suggests that estrogen, rather than progesterone, may be a detrimental factor of constipation caused by female sex steroid hormones, however, it does not show agreement with some reports [21-23] suggesting that progesterone is an important risk factor for constipation in women, and this hypothesis was supported by results indicating that females had greater frequency of constipation during menses [24,25] and pregnancy [5]. High progesterone levels contribute to inhibition of bowel motility and cause constipation [26]. However, findings of a recent study suggested the possibility that estrogen, rather than progesterone, may be responsible for the delay in gastric emptying and increase in colonic transit time observed in pregnancy [27]. Parenteral administration of estradiol, the predominant estrogen during reproductive years, to rats resulted in inhibited gastric emptying [28]. On the other hand, female rats treated with progesterone did not show a decrease in colon myoelectric signal, suggesting no constipation by female sex steroid hormones in virgin female rats [29]. Our study involving administration of female sex steroid hormones, such as estrogen and progesterone to male mice, appears to be the first study to evaluate the effect of these hormones on constipation. In conclusion, estrogen, rather than progesterone, may be a detrimental factor of constipation via decreased bowel movement in mice.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Yeungnam University research grant in 2010.

Go to :

References

1. Chatoor D, Emmnauel A. Constipation and evacuation disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009; 23:517–530. PMID: 19647687.

2. Foxx-Orenstein AE, McNally MA, Odunsi ST. Update on constipation: one treatment does not fit all. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008; 75:813–824. PMID: 19068963.

3. Peppas G, Alexiou VG, Mourtzoukou E, Falagas ME. Epidemiology of constipation in Europe and Oceania: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008; 8:5. PMID: 18269746.

4. Chang L, Toner BB, Fukudo S, Guthrie E, Locke GR, Norton NJ, Sperber AD. Gender, age, society, culture, and the patient's perspective in the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006; 130:1435–1446. PMID: 16678557.

5. Wald A, Van Thiel DH, Hoechstetter L, Gavaler JS, Egler KM, Verm R, Scott L, Lester R. Effect of pregnancy on gastrointestinal transit. Dig Dis Sci. 1982; 27:1015–1018. PMID: 7140485.

6. Gill RC, Bowes KL, Kingma YJ. Effect of progesterone on canine colonic smooth muscle. Gastroenterology. 1985; 88:1941–1947. PMID: 3996847.

7. Shah S, Hobbs A, Singh R, Cuevas J, Ignarro LJ, Chaudhuri G. Gastrointestinal motility during pregnancy: role of nitrergic component of NANC nerves. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000; 279:R1478–R1485. PMID: 11004018.

8. Hutson WR, Roehrkasse RL, Wald A. Influence of gender and menopause on gastric emptying and motility. Gastroenterology. 1989; 96:11–17. PMID: 2909416.

9. Jung HK, Kim DY, Moon IH. Effects of gender and menstrual cycle on colonic transit time in healthy subjects. Korean J Intern Med. 2003; 18:181–186. PMID: 14619388.

10. Guyton AC, Hall JE. Textbook of medical physiology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders;2006. p. 1013.

11. Wald A, Van Thiel DH, Hoechstetter L, Gavaler JS, Egler KM, Verm R, Scott L, Lester R. Gastrointestinal transit: the effect of the menstrual cycle. Gastroenterology. 1981; 80:1497–1500. PMID: 7227774.

12. Madsen JL. Effects of gender, age, and body mass index on gastrointestinal transit times. Dig Dis Sci. 1992; 37:1548–1553. PMID: 1396002.

13. Soffer EE, Kongara K, Achkar JP, Gannon J. Colonic motor function in humans is not affected by gender. Dig Dis Sci. 2000; 45:1281–1284. PMID: 10961704.

14. Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Müller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999; 45(Suppl 2):II43–II47. PMID: 10457044.

15. Surrenti E, Rath DM, Pemberton JH, Camilleri M. Audit of constipation in a tertiary referral gastroenterology practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995; 90:1471–1475. PMID: 7661172.

16. Knowles CH, Scott SM, Rayner C, Glia A, Lindberg G, Kamm MA, Lunniss PJ. Idiopathic slow-transit constipation: an almost exclusively female disorder. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003; 46:1716–1717. PMID: 14668603.

17. Preston DM, Lennard-Jones JE. Severe chronic constipation of young women: 'idiopathic slow transit constipation'. Gut. 1986; 27:41–48. PMID: 3949236.

18. Thomas ML, Xu X, Norfleet AM, Watson CS. The presence of functional estrogen receptors in intestinal epithelial cells. Endocrinology. 1993; 132:426–430. PMID: 8419141.

19. Ryan JP, Pellecchia D. Effect of progesterone pretreatment on guinea pig gallbladder motility in vitro. Gastroenterology. 1982; 83:81–83. PMID: 6281127.

20. Bruce LA, Behsudi FM. Differential inhibition of regional gastrointestinal tissue to progesterone in the rat. Life Sci. 1980; 27:427–434. PMID: 7412484.

21. Xiao ZL, Pricolo V, Biancani P, Behar J. Role of progesterone signaling in the regulation of G-protein levels in female chronic constipation. Gastroenterology. 2005; 128:667–675. PMID: 15765402.

22. Cong P, Pricolo V, Biancani P, Behar J. Abnormalities of prostaglandins and cyclooxygenase enzymes in female patients with slow-transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2007; 133:445–453. PMID: 17681165.

23. Xiao ZL, Biancani P, Behar J. Effects of progesterone on motility and prostaglandin levels in the distal guinea pig colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009; 297:G886–G893. PMID: 20501437.

24. Kane SV, Sable K, Hanauer SB. The menstrual cycle and its effect on inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: a prevalence study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998; 93:1867–1872. PMID: 9772046.

25. Heitkemper MM, Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Burr RL, Hertig V, Bond EF. Symptoms across the menstrual cycle in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003; 98:420–430. PMID: 12591063.

26. Celik AF, Turna H, Pamuk GE, Pamuk ON. How prevalent are alterations in bowel habits during menses? Dis Colon Rectum. 2001; 44:300–301. PMID: 11227952.

27. Shah S, Nathan L, Singh R, Fu YS, Chaudhuri G. E2 and not P4 increases NO release from NANC nerves of the gastrointestinal tract: implications in pregnancy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001; 280:R1546–R1554. PMID: 11294780.

28. Chen TS, Doong ML, Chang FY, Lee SD, Wang PS. Effects of sex steroid hormones on gastric emptying and gastrointestinal transit in rats. Am J Physiol. 1995; 268:G171–G176. PMID: 7840200.

29. Speranzini LB, Lopasso PP, Laudanna AA. Progesterone, estrogen and pregnancy do not decrease colon myoelectric activity in rats: an in vivo study. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2008; 66:53–58. PMID: 18319603.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download