Abstract

Purpose

Ocular manifestations in snake-bite injuries are quite rare. However, the unusual presentations, diagnosis and their management can pose challenges when they present to the ophthalmologist. Early detection of these treatable conditions can prevent visual loss in these patients who are systemically unstable and are unaware of their ocular condition. To address this, a study was conducted with the aim of identifying the various ocular manifestations of snake bite in a tertiary care center.

Methods

This is a one-year institute-based prospective study report of 12 snake bite victims admitted to a tertiary hospital with ocular manifestations between June 2013 to June 2014, which provides data about the demographic characteristics, clinical profiles, ocular manifestations, and their outcomes.

Results

Twelve cases of snake bite with ocular manifestations were included of which six were viper bites, three were cobra bites and three were unknown bites. Six patients presented with bilateral acute angle closure glaucoma (50%), two patients had anterior uveitis (16.6%) of which one patient had concomitant optic neuritis. One patient had exudative retinal detachment (8.3%), one patient had thrombocytopenia with subconjunctival hemorrhage (8.3%) and two patients had external ophthalmoplegia (16.6%).

Conclusions

Bilateral angle closure glaucoma was the most common ocular manifestation followed by anterior uveitis and external ophthalmoplegia. Snake bite can result in significant ocular morbidity in a majority of patients but spontaneous recovery with anti-snake venom, steroids and conservative management results in good visual prognosis.

Poisonous snakes are found throughout the world, and India, being a tropical country, forms a habitat for a great variety of snakes. Nearly 60,000 people are bitten by snakes every year in the Indian subcontinent with a mortality rate of 25% [1]. Snake venoms are complex heterogeneous poisons having multiple effects. However, ophthalmic complications in snake bite are rare [12]. A review of literature on ocular effects of snake bite cited only isolated case reports describing angle closure glaucoma, optic neuritis, external ophthalmoplegia and vitreous haemorrhage following snake bite resulting in blindness. Early detection of these treatable conditions can prevent visual loss in these patients who are unaware of their ocular condition owing to their systemic condition. The present study was conducted with an aim to identify the various ocular manifestations of snake bite and the objective of the study was to study the management of these conditions, their outcomes and residual ocular morbidity if any. We report a series of cases of various unusual ophthalmic manifestations of snake bite, treatment and their outcome observed over one year in a tertiary care center in India.

The study was conducted in a tertiary eye care center in South India from June 2013 to June 2014. Institute ethics committee approval was obtained for the study. All patients with venomous snake bites admitted to the hospital during this one year period were included in the study. Demographic details like age and gender were recorded. Information regarding the type of snake bite, time of presentation following the bite, systemic manifestations, treatment received, and the clinical outcome were recorded in all the cases. Ocular examination was done in all patients admitted to the hospital emergency department irrespective of their complaints as most of these patients were systemically unstable and could not complain of their ocular symptoms. Treatment was initiated according to the ocular condition detected and response to treatment and any residual ocular morbidity were recorded.

A total of 170 venomous snake bite victims were admitted over a one-year period. Twelve cases (7.05%) out of 170 victims had ocular involvement. Age ranged from 13 to 53 years. Out of the twelve with ocular involvement, ten (83.33%) were males and two (16.66%) were females. Viper bite was the most common snake bite seen in six patients (50%), followed by cobra in three patients (25%), and unidentified venomous snake in three patients (25%) (Table 1). All patients were initially evaluated and managed in the emergency department and ocular evaluation was done after systemic stabilization. All patients in the study received polyvalent anti-snake venom (ASV) (Haffkine Institute, Mumbai, India). Two patients succumbed to acute renal failure.

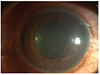

A 32-year-old male presented with a history of an unknown snake bite, was systemically stable, and presented with sudden onset redness in both eyes (OU). On examination, there was subconjunctival hemorrhage OU (Fig. 1). The remainder of the ocular examination was unremarkable. Platelet count was 16,000 per microliter. Patient was reassured, and the subconjunctival hemorrhage resolved after two weeks.

A 25-year-old male presented with history of a viper bite, was systemically stable and received ASV. There was a history of pain and redness OU since the bite. On examination the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 6 / 12 OU, and anterior chamber showed grade 3 cells and flare. The remainder of the ocular examination was normal. The patient was diagnosed with acute anterior uveitis OU and was started on topical steroids and cycloplegics for one week, and uveitis resolved completely and visual acuity returned to normal.

Six patients presented with a history of pain, redness and sudden onset diminution of vision OU after an average of six hours following snake bite. Four (66.66%) had viper bite, one (16.66%) had cobra bite, and one (16.66%) was an unknown bite. Cornea was hazy and edematous with shallow anterior chamber. Pupils were mid-dilated and fixed with no response to light. Average intraocular pressure recorded was in the range of 38 to 44 mmHg. A diagnosis of acute angle closure glaucoma OU following snake bite was made in these cases. Treatment was initiated with intravenous mannitol and oral acetazolamide 250 mg stat, followed by four times daily. Next, topical timolol and pilocarpine eye drops were then administered. After this treatment, intraocular pressure reduced to 28 mmHg in three patients. Patients were continued on acetazolamide and topical medications for four days at which time intraocular pressure returned to normal with a reduction in corneal haze. Three patients were systemically unstable on dialysis for acute renal failure and received only topical anti-glaucoma medications. Of these three patients, two succumbed to death.

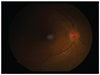

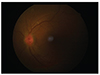

A 35-year-old male with a history of a viper bite, was treated with ASV. He presented to us on the sixth day following the bite with sudden onset pain and blurring of vision OU for four days. BCVA was 6 / 60 OU. Examination OU revealed keratic precipitates, grade 3 cells and flare, posterior synechiae with sluggish and ill-sustained pupillary reflex (Figs. 2 and 3). Fundoscopy revealed hyperemic and edematous disc and the rest of the fundus was normal (Figs. 4 and 5). There was total red-green deficiency OU. Neuroimaging was normal. Visual evoked potentials revealed prolonged latency and decreased amplitudes in OU. A diagnosis of acute anterior uveitis and concomitant optic neuritis OU was made, and the patient was started on topical steroids, cycloplegics and intravenous methylprednisolone 250 mg daily for 3 days with symptomatic improvement. Topical medications were continued, and he was started on oral prednisolone, tapered over three weeks, after which time BCVA improved to 6 / 12 with complete resolution of uveitis and disc edema.

A 13-year-old male presented with a history of an unknown snake bite, received ASV and presented with sudden onset diminution of vision in the left eye (OS) for one day. Visual acuity OS was perception of light with an accurate projection of rays. Anterior segment examination OU was unremarkable. Fundus OS revealed exudative retinal detachment reaching the macula. The patient was started on oral steroids tapered over four weeks, after which time visual acuity improved to 6 / 12 with resolution of the detachment.

Two patients that presented with a history of cobra bite and, were systemically unstable developed sudden onset ptosis within a few hours following the bite. One patient was a male and the other was a female. On examination, there was complete ptosis OU with limitation of extraocular movements in all cardinal directions of gaze. A diagnosis of external ophthalmoplegia following snake bite was made and patients were kept for follow up to observe recovery. The male patient, after receiving AS, showed improvement. Ptosis and ophthalmoplegia subsided over a period of three weeks. The female, following systemic recovery, was lost for follow up. On follow up after six months, she continued to have severe ptosis, hypertropia and exotropia of both eyes with a positive forced duction test (Figs. 6 and 7). She underwent strabismus correction and frontalis sling surgery for ptosis as a staged procedure.

Venomous snake bites result in multisystem derangements. Ocular manifestations of snake bite are usually rare. Snake venom is a complex heterogeneous poison that can result in multisystem toxicity. The majority of the cases in our study were males, which is in accordance with other epidemiological studies from India as reported by Halesha et al. [3] and Jarwani et al. [4]. Males are the most common victims of snake bite probably due to their outdoor occupation. Viper bite was the most common snake bite accounting for 50% cases in our study. This is in contrast to other studies from India where neurotoxic snake bite was reported to be the most common followed by viper bite [45]. Various ocular manifestations of snake bite described in the literature are bilateral angle closure glaucoma, chemical injury to the eye from spitting of highly irritant snake venom [67], direct injury to the eye leading to penetrating injuries with bite marks, conjunctival and corneal lacerations [8]. Subconjunctival hemorrhages and hyphema due to the systemic hematotoxicity, keratomalacia due to collagenase in the snake venom causing stromal lysis, uveitis as a result of serum sickness-like response occurring due to ASV or direct toxicity of venom in penetrating injuries and endophthalmitis have also been reported [91011].

We are the first to describe a series of cases with ocular involvement resulting from the effects of snake venom or ASV as a treatment modality in these patients. Twelve patients (7.05%) out of one hundred seventy patients had ocular involvement in the study. Anterior segment involvement was more common, seen in eight patients (66.66%) followed by involvement of the posterior segment in two cases (16.66%) and ophthalmoplegia in two cases (16.66%).

Bilateral acute angle closure glaucoma was the most common manifestation and the most common anterior segment manifestation seen in six cases (75%) followed by anterior uveitis (16.6%). All these cases received ASV. Most of the cases of angle closure glaucoma were secondary to hemotoxic snake bite.

The mechanism of acute angle closure glaucoma following snake bite is not known. We hypothesize it to occur as a result of the capillary damage due to snake venom, producing ciliary body edema and forward movement with pupillary block and subsequent angle closure [12]. This hypothesis explains the mechanism of angle closure with a hemotoxic snake bite. But in the study, there was a case of acute angle closure following a neurotoxic (Cobra) bite. Idiosyncratic reaction to ASV resulting in the development of ciliary body edema resulting in subsequent angle closure can explain the mechanism in such cases. Usually these cases show complete resolution with medical management. Certain cases pose challenges in treatment unlike cases of primary angle closure glaucoma because of their systemic instability which precludes use of hyperosmotic agents and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Two (33.33%) cases succumbed to renal failure with ocular involvement as a factor suggesting severe envenomation and thus, ocular involvement should be considered a factor for predicting survival in such patients.

One patient (12.5%) had acute anterior uveitis, the second most common anterior segment manifestation observed in our case series. Uveitis in snake bite can be due to the direct toxic effect of the snake venom or hypersensitivity reaction to ASV. One patient (12.5%) had subconjunctival hemorrhage secondary to reduced platelet count following a hemotoxic snake bite.

The posterior segment manifestations described in the literature include case reports describing central retinal artery occlusion, macular infarcts, and; retinal and vitreous hemorrhages following a snake bite [131415].

The present article describes a rare presentation of optic neuritis with concomitant anterior uveitis following a snake bite. The blurred vision that occurred in the patient on the second day was probably due to the development of acute anterior uveitis due to the toxicity of snake venom, and the severe diminution of vision that occurred over the next four days can be attributed to the worsening of acute anterior uveitis due to a concomitant allergy to ASV, leading to the development of optic disc edema. Pulse steroid therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone proved to be effective in our patient, as it was in a similar case of optic neuritis treated with methyl prednisolone as reported by Menon et al. [16].

Exudative retinal detachment following a snake bite is reported here for the first time. The cause of exudative retinal detachment is not known. We hypothesize that toxins present in venom of a hemotoxic snake bite leads to capillary damage resulting in widespread choroidopathy, causing massive exudation of fluid into the subretinal space resulting in exudative retinal detachment. However, the development of the condition in one eye cannot be explained. Furthermore, studies need to be conducted to discern the exact pathogenetic mechanism of exudative retinal detachment.

Bilateral ptosis and ophthalmoplegia are two of the most common ocular manifestations resulting from the systemic toxicity of neurotoxic snake bites [17]. Two patients in the study had ptosis with external ophthalmoplegia. Both of these cases were secondary to neurotoxic snake bite. The venom of elapids is rich in phospholipase A2 and other proteins, which are potent neurotoxins affecting the neuromuscular transmission at either presynaptic or post-synaptic levels. Presynaptic-acting neurotoxins (called β-neurotoxins) inhibit the release of acetylcholine, while post-synaptic-acting neurotoxins (called α-neurotoxins) cause a reversible blockage of acetylcholine receptors [18]. Extraocular muscles are affected early due to the peculiar structure of fast twitch fibers and the nerve: muscle ratio being 1 : 5 to 1 : 10 when compared to skeletal muscle that is 1 : 100. The onset can vary from 3 min to several hours from the time of the bite and usually recovers completely with ASV or anticholinesterase therapy. One patient in the study resolved completely with administration of ASV whereas the other patient was lost to follow up and presented to us with restrictive strabismus secondary to long-standing paralytic squint following snake bite which necessitated a staged procedure. Ptosis was corrected with frontalis sling suspension OU and the hypertropia with exotropia was corrected by a recess resect procedure.

In summary, bilateral angle closure glaucoma was the most common ocular manifestation followed by anterior uveitis and external ophthalmoplegia. Snake bite can result in significant ocular morbidity in a majority of patients but spontaneous recovery with ASV, steroids and conservative management result in good visual prognosis. It also highlights the fact that, even though ASV remains the mainstay of treatment for snake bite, it is not free of adverse effects, and the treating physician needs to be aware of these rare complications of snake bite and ASV therapy. The present study could not ascertain whether snake venom or the ASV was the causative factor for the various manifestations seen in the case series. Furthermore studies need to be conducted to determine the exact etiology and pathogenetic mechanisms of various manifestations of snake bite.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Kasturiratne A, Wickremasinghe AR, de Silva N, et al. The global burden of snakebite: a literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med. 2008; 5:e218.

2. Adukauskiene D, Varanauskiene E, Adukauskaite A. Venomous snakebites. Medicina (Kaunas). 2011; 47:461–467.

3. Halesha BR, Harshavardhan L, Lokesh AJ, et al. A study on the clinico-epidemiological profile and the outcome of snake bite victims in a tertiary care centre in southern India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013; 7:122–126.

4. Jarwani B, Jadav P, Madaiya M. Demographic, epidemiologic and clinical profile of snake bite cases, presented to Emergency Medicine department, Ahmedabad, Gujarat. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2013; 6:199–202.

5. Raina S, Raina S, Kaul R, et al. Snakebite profile from a medical college in rural setting in the hills of Himachal Pradesh, India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014; 18:134–138.

6. Gilkes MJ. Snake venom conjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1959; 43:638–639.

7. Chu ER, Weinstein SA, White J, Warrell DA. Venom ophthalmia caused by venoms of spitting elapid and other snakes: report of ten cases with review of epidemiology, clinical features, pathophysiology and management. Toxicon. 2010; 56:259–272.

8. Chen CC, Yang CM, Hu FR, Lee YC. Penetrating ocular injury caused by venomous snakebite. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005; 140:544–546.

9. Kleinman DM, Dunne EF, Taravella MJ. Boa constrictor bite to the eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998; 116:949–950.

10. Nayak SG, Satish R, Nityanandam S, Thomas RK. Uveitis following anti-snake venom therapy. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2007; 13:130–134.

11. Iqbal M, Khan BS, Ahmad I. Endogenous endophthalmitis associated with snake bite. Pak J Ophthalmol. 2009; 25:114–116.

12. Srinivasan R, Kaliaperumal S, Dutta TK. Bilateral angle closure glaucoma following snake bite. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005; 53:46–48.

13. Hayreh SS. Transient central retinal artery occlusion following viperine snake bite. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008; 126:870–871.

14. Singh J, Singh P, Singh R, Vig VK. Macular infarction following viperine snake bite. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007; 125:1430–1431.

15. Rao BM. A case of bilateral vitreous haemorrhage following snake bite. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1977; 25:1–2.

16. Menon V, Tandon R, Sharma T, Gupta A. Optic neuritis following snake bite. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1997; 45:236–237.

17. Takeshita T, Yamada K, Hanada M, et al. Case report: extraocular muscle paresis caused by snakebite. Kobe J Med Sci. 2003; 49:11–15.

18. Del Brutto OH, Del Brutto VJ. Neurological complications of venomous snake bites: a review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012; 125:363–372.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download