Abstract

We studied three patients who developed left unilateral punctate keratitis after suffering left-sided Wallenberg Syndrome. A complex evolution occurred in two of them. In all cases, neurophysiological studies showed damage in the trigeminal sensory component at the bulbar level. Corneal involvement secondary to Wallenberg syndrome is a rare cause of unilateral superficial punctate keratitis. The loss of corneal sensitivity caused by trigeminal neuropathy leads to epithelial erosions that are frequently unobserved by the patient, resulting in a high risk of corneal-ulcer development with the possibility of superinfection. Neurophysiological studies can help to locate the anatomical level of damage at the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve, confirming the suspected etiology of stroke, and demonstrating that prior vascular involvement coincides with the location of trigeminal nerve damage. In some of these patients, oculofacial pain is a distinctive feature.

Wallenberg syndrome consists of a set of signs and symptoms caused by occlusion of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery [1]. This syndrome encompasses symptoms such as vertigo from vestibular damage; diplopia from pontine involvement; dysphonia, dysphagia, and dysarthria caused by damage at the nucleus ambiguus; ipsilateral facial pain from trigeminal nerve involvement; hypoalgesia and thermoanaesthesia in the trunk and limbs contralateral to the lesion from spinothalamic tract damage; and ipsilateral face hypoalgesia and thermoanaesthesia from trigeminal nerve involvement (crossed brainstem syndrome) [2].

Ipsilateral Horner syndrome may occur due to damage to the descending sympathetic pathway, while central nystagmus or a decreased blink reflex may occur as a result of an ipsilateral trigeminal injury [3].

The corneal sensory nerves are essential for ensuring the integrity of the corneal epithelium, and their loss causes an imbalance in the metabolic activity of epithelial cells, producing a loss of the microvilli that are responsible for maintaining the mucin layer of the tear film [4]. Therefore, the eye becomes vulnerable to infection and even minor trauma. Although the mechanisms of protection provided by the blink reflex and tear secretion are preserved, these are insufficient to compensate for the vulnerable state of these corneas.

Trigeminal nerve injury may be due to various causes, including vascular problems, herpes, diabetes mellitus, corneal dystrophies, and congenital defects. In addition to the classical causes, trigeminal nerve injury also has been described in demyelinating diseases, abscesses, metastases, bruising, and post-radiation necrosis [5]. The main impact on the cornea is the development of epithelial erosions and corneal ulceration, leading to a slow healing process.

In adult patients with unilateral keratitis, the leading cause to be considered is a herpes virus, such as herpes simplex. However, patients may not remember previous episodes or may have suffered "herpes sine herpete" from the varicella zoster virus [6]. In addition, other possible causes must be ruled out such as eye-drop toxicity or hyposecretion.

We present three challenging cases with trigeminal nerve involvement because of a vertebrobasilar artery stroke (Wallenberg syndrome). The focus is on a differential diagnosis of unilateral punctate keratitis, the limited knowledge regarding the relationship between unilateral keratitis and Wallenberg syndrome, and the importance of proper therapeutic management given the potential risks associated with this pathology.

A 77-year-old woman suffered Wallenberg syndrome after a stroke in the territory of the left vertebrobasilar artery. Three years later, she came to our hospital complaining of chronic lancinating left eye (OS) pain of two years' duration. She was being treated in the pain unit for left hemifacial pain, and she had no history of herpes zoster ophthalmicus.

The patient's best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in the right eye (OD) was 1 and in the OS was 0.3. In the OS, she was found to have corneal anaesthesia in all four quadrants by examination with cotton swabs; a thin meniscus; a tear break-up time of 1 second; and a severe confluent superficial punctate keratitis at the interpalpebral fissure, Oxford grade IV. Schirmer's test without anaesthesia produced results of 5 mm in the OD and 1 mm in the OS (Fig. 1).

The treatments prescribed were artificial tears containing 0.1% hyaluronic acid (HA GenTeal; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA) every 8 hours, with nightly carbomer lubricating eye drops 0.2% (Lipolac ophthalmic gel; Farma-lepori, Berlin, Germany), and autologous serum eye drops (CSA) at 20% four times a day. Silicone punctal plugs were placed in the upper and lower points.

A neurophysiological study of the trigeminal nerve showed chronic partial injury to a moderate degree. The distribution of neurophysiological findings demonstrated nerve involvement in the spinal trigeminal tract at the bulbar level, without evidence of facial nerve injury or peripheral polyneuropathy. With treatment, the patient improved her visual acuity up to 0.5 in OS, although a superficial punctate keratitis of Oxford grade II remained.

A 72-year-old woman presented with a history of left ischaemic Wallenberg syndrome one year prior, and suffered from OD amblyopia. She was referred from the emergency department for a corneal ulcer in the OS. Ophthalmologic examination showed a BCVA in the OD of 0.15 and in the OS of 0.3. In the OS, a central corneal ulcer was surrounded by superficial punctate keratitis, grade III on the Oxford scale; associated with corneal anaesthesia in all four quadrants; and lagophthalmos. Schirmer's test without anaesthesia was 20 mm for the OD and 6 mm for the OS. The proposed treatments were lubricating eye drops four times a day (Systane; Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA), dexpanthenol gel twice a day (Recugel; Bausch & Lomb, Berlin, Germany), gentamicin ointment at night (Oculos epithelializing; Thea, Clermont-Ferrand Cedex 2, France) and autologous serum eye drops at 20% four times a day. Four months later, the patient showed a BCVA of 0.7 in the OS and superficial punctate keratitis in the interpalpebral fissure, Oxford grade II.

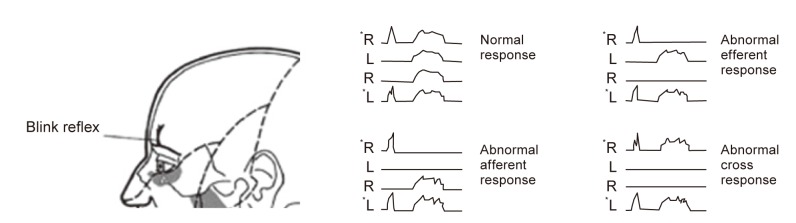

A neurophysiological study showed a partial lesion of the sensory component in the left trigeminal nerve, with preservation of the motor component. Blink reflexes showed increased late responses to stimulation of the first left branch of the trigeminal nerve (Fig. 2).

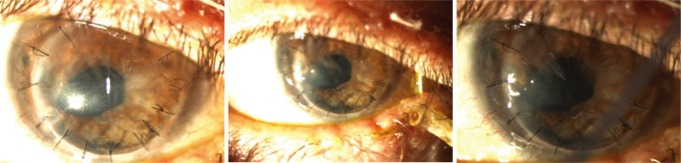

A 58-year-old woman was referred because of a persistent epithelial defect following corneal transplantation in the OS. She had presented with two corneal abscesses in the OS within the past 7 years, and a penetrating keratoplasty with an amniotic membrane graft had been performed 4 months earlier because of corneal leukoma. After the surgery, the patient maintained treatment with topical 0.3% tobramycin and 0.1% dexamethasone every 6 hours (Tobradex, Alcon). She had reported a cerebral ischaemic event in the left cerebral territory eight years earlier that led to a residual right hemihypoesthesia. The BCVA was 0.7 in the OD and count fingers (CF) in the OS. In the OS, receiver sensitivity in the peripheral and central cornea were abolished. The corneal button had an epithelial defect 3.5 mm in diameter with central stromal thinning, and in the anterior chamber there was a hypopyon level of 1.5 mm (Fig. 3). Schirmer's test without anaesthesia was 12 mm in the OD and 2 mm in the OS.

Corneal cultures were taken for bacteria, fungi, and herpes family polymerase chain reaction, varicella zoster virus, herpes simplex virus I and II, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, virus herpes 6, which were all negative. The prescribed treatment was moxifloxacin (Vigamox eye drops, Alcon) every 3 hours; 0.3% tobramycin eye drops; dexamethasone 0.1% reduced to every 12 hours (Tobradex, Alcon); 1 tablet of 500 mg valacyclovir every 24 hours (Valtrex; Glaxo SmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA); prednisone 15 mg daily (10 mg Prednisolone tablets Alonga; Sanofi-aventis, Quebec, Canada); 3% trehalose eye drops four times a day (Thealoz, Thea); and one tablet of doxycycline daily (100 mg Vibracina; Invicta Farma, Madrid, Spain). A contact lens was placed, and a central and temporary tarsorrhaphy was performed. Autologous serum eye drop treatment was not possible because of a positive hepatitis C virus serology.

The evolution was satisfactory, and at the last visit two months later, OS examination showed a BCVA of 0.3 despite the leukoma and the irregular epithelium at the corneal button (Fig. 4).

The neurophysiological study showed a left trigeminal nerve lesion at the bulbar level. No changes were observed in the facial and right trigeminal nerves. Oral valacyclovir treatment (Valtrex, Glaxo SmithKline) was stopped after the neurophysiological results.

Corneal injury secondary to Wallenberg syndrome is a rare cause of unilateral keratitis, as the only reported case was presented in the following article: "Persistent visual loss from neurotrophic corneal ulceration after dorsolateral medullary infarction (Wallenberg syndrome)" [3]. The case described a 48-year-old patient suffering from a corneal abscess ipsilateral to a previous spinal cord infarction. As is typical, the patient lacked corneal sensitivity in the affected eye. For this reason, he developed an infiltrated corneal ulcer with stromal involvement and hypopyon that was unobserved by the patient until a late stage of the disorder, leaving a residual visual acuity of CF.

The diagnosis of trigeminal damage at the ophthalmic branch level can be easily achieved by scanning for corneal sensitivity by inducing the blink reflex using a swab to the cornea. The neurophysiological findings help us to locate the precise anatomical level of the trigeminal pathway [7,8]. These tests are not regularly required for unilateral keratitis, but will help to confirm the suspected aetiology if the patient had a previous stroke, demonstrating that prior vascular involvement is related to the location of the trigeminal damage detected by neurophysiology. Radiological nuclear magnetic resonance findings in Wallenberg syndrome show a characteristic hypointense sequence on T1 and a hyperintense signal on T2 at the brainstem lesion [7]. The neurophysiological study of this pathology.by electroneurography of the trigeminal nerve.reveals the location of sensory trigeminal nerve fibre involvement at the level of the spinal tract nucleus in the posterolateral region of the bulb, secondary to vascular obstruction in this brain stem region. In some cases, involvement of adjacent facial nerve fibres is also observed.

The blink reflex is used to evaluate the integrity of the cranial nerves, including the trigeminal and facial nerves, and the intensity and level of damage. The electrical signals read by the electrode placed at this level enabled us to interpret the results [9]. This is a qualitative test that does not correlate with keratitis severity level.

We confirmed by neurophysiological study that the cause of unilateral keratitis in all cases was located at the central level. Our three case studies were exposed to a differential diagnosis that included unilateral keratitis (mainly herpetic in origin). We were able to avoid unnecessary treatments and performed careful patient monitoring while improving the patients' visual acuity and quality of life.

Normally, patients who suffer neurotrophic keratitis do not report pain. However, as we found in our first case, patients can report eye pain, which may be related to ipsilateral facial pain. Trigeminal neuralgia caused by a stroke is not frequent, and it is also unusual to find facial pain in a patient with Wallenberg syndrome. Facial pain in Wallenberg syndrome seems to be correlated with ischaemic lesions produced at the trigeminal tract, with the trigeminal spinal nucleus subsequently developing trigeminal neuralgia. This may cause chronic and disabling facial pain most effectively treated with gabapentin [2].

As two of our cases show, loss of corneal sensitivity due to trigeminal nerve involvement results in the appearance of epithelial erosions. Initially, the erosions may be unobserved by patients with systemic complications (i.e., strokes), but to prevent the progression and development of corneal ulcers with secondary infection and abscess formation, early detection is important, especially as the resolution process may be time-consuming and costly. As a result, patients with Wallenberg syndrome should undergo comprehensive ophthalmologic examinations, including slit-lamp examination, corneal esthesiometer, and Schirmer's test, to rule out trigeminal nerve injury and to grade severity of anterior segment damage. In these patients, the ophthalmologist should consider prophylactic treatment, including lubricating eye drops.

The signs of neurotrophic keratitis may present years after an ischemic event (e.g., case 3) and have various manifestations, such as corneal erosions, persistent epithelial defects/ulcerations, and even hypopyon, which can mimic infectious keratitis.

Therapeutic measures in cases of punctate keratitis include the daily periodic application of artificial tears, night creams, and autologous serum [10,11]. Ocular occlusion and nasal strips arranged perpendicular to the lid margin promote healing of erosions [12]. Additional procedures such as punctal plugs, amniotic membrane implantation, and surgical tarsorrhaphy may become necessary if the disease worsens [13,14].

Multidisciplinary management may be required for these patients. Neurology specialists should contemplate this pathology in order to refer these patients to the ophthalmology department.

Wallenberg syndrome should be included in ophthalmology procedure manuals regarding the differential diagnosis of unilateral keratitis in order to ensure proper medical management. Ophthalmologists also should take careful patient histories and should consider neurological causes of neurotrophic keratitis.

Finally, radiological and neurophysiological studies are relevant techniques to establish the location and cause of unilateral corneal injuries in patients with previous central neurological damage.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the help and support received from the Ophthalmology and Neurophysiology Services of Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain.

References

1. Komiya H, Saeki N, Iwadate Y, et al. Posterior inferior cerebellar artery dissecting aneurysm presenting with Wallenberg's syndrome: case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1988; 28:404–408. PMID: 2457849.

2. Ordas CM, Cuadrado ML, Simal P, et al. Wallenberg's syndrome and symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia. J Headache Pain. 2011; 12:377–380. PMID: 21308475.

3. Hipps WM, Wilhelmus KR. Persistent visual loss from neurotrophic corneal ulceration after dorsolateral medullary infarction (Wallenberg syndrome). J Neuroophthalmol. 2004; 24:345–346. PMID: 15662254.

4. Oduntan AO. Cellular inflammatory response induced by sensory denervation of the conjunctiva in monkeys. J Anat. 2005; 206:287–294. PMID: 15733301.

5. Suzuki N, Mizuno H, Nakashima I, Itoyama Y. Herpes labialis in multiple sclerosis with a trigeminal lesion. Intern Med. 2011; 50:259. PMID: 21297331.

6. Suresh PS, Tullo AB. Herpes simplex keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1999; 47:155–165. PMID: 10858770.

7. Ross MA, Biller J, Adams HP Jr, Dunn V. Magnetic resonance imaging in Wallenberg's lateral medullary syndrome. Stroke. 1986; 17:542–545. PMID: 3715957.

8. Cruccu G, Iannetti GD, Marx JJ, et al. Brainstem reflex circuits revisited. Brain. 2005; 128(Pt 2):386–394. PMID: 15601661.

9. Aramideh M, Ongerboer de Visser BW. Brainstem reflexes: electrodiagnostic techniques, physiology, normative data, and clinical applications. Muscle Nerve. 2002; 26:14–30. PMID: 12115945.

10. Jeng BH, Dupps WJ Jr. Autologous serum 50% eyedrops in the treatment of persistent corneal epithelial defects. Cornea. 2009; 28:1104–1108. PMID: 19730088.

11. Poon AC, Geerling G, Dart JK, et al. Autologous serum eyedrops for dry eyes and epithelial defects: clinical and in vitro toxicity studies. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001; 85:1188–1197. PMID: 11567963.

12. Magone MT, Seitzman GD, Nehls S, Margolis TP. Treatment of neurotrophic keratopathy with nasal dilator strips. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005; 89:1529–1530. PMID: 16234466.

13. Prabhasawat P, Tesavibul N, Komolsuradej W. Single and multilayer amniotic membrane transplantation for persistent corneal epithelial defect with and without stromal thinning and perforation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001; 85:1455–1463. PMID: 11734521.

14. Chen HJ, Pires RT, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation for severe neurotrophic corneal ulcers. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000; 84:826–833. PMID: 10906085.

Fig. 2

Blink reflex (neurophysiological examination). This technique involves placing an electrode in the orbicularis oculi muscle and a reference electrode in the outer canthus, and then recording the electrical response (mA). *Stimulation.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download