Abstract

Livedoid vasculopathy (LV) is characterized by a long history of ulceration of the feet and legs and histopathology indicating a thrombotic process. We report a case of acute central retinal artery occlusion in a 32-year-old woman who had LV. She showed no discernible laboratory abnormalities such as antiphospholipid antibodies and no history of cerebrovascular accidents. Attempted intra-arterial thrombolysis showed no effect in restoring retinal arterial perfusion or vision. The central retinal artery occlusion accompanied by LV in this case could be regarded as a variant form of Sneddon's syndrome, which is characterized by livedo reticularis and cerebrovascular accidents.

Livedoid vasculopathy (LV) is characterized by livedo reticularis (a mottled reticulated lace-like purplish skin discoloration) combined with outbreaks of painful purpuric, necrotic lesions on both legs simultaneously, mainly in the malleolar region and on the soles of the feet [1]. The histopathological findings of LV are occlusion of dermal vessels by intravascular fibrin, segmental hyalinization, and endothelial proliferation, which indicates a thrombotic process. The absence of fibrinoid necrosis and inflammation of the vessel wall differentiates LV from true vasculitis [1]. Retinal artery occlusion has been reported among patients with vasculitis, including systemic lupus erythematosus [2], Wegener granulomatosis [3], and fibromuscular dysplasia [4]. To date, there have been no reports of retinal artery occlusion associated with LV. There have been a few case reports of retinal artery occlusion associated with Sneddon's syndrome, which is characterized by livedo reticularis and cerebrovascular lesions [5-9].

Here, we report a case of acute central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) associated with LV, the angiographic findings, and the results of intra-arterial thrombolysis. The acute CRAO as an atypical form of cerebrovascular lesion and the young age of this patient (middle-aged female) and dermatologic lesions (LV) indicate that this case is a variant of Sneddon's syndrome.

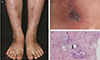

A 32-year-old Korean woman found that she had visual loss in her right eye when she woke up in the morning and was referred to our clinic for acute CRAO 16 hours after symptom occurrence. Eight years prior, she had presented with itching and tender violaceous erythematous non-elevated patches with central necrotic vesicle on the dorsum of both the lower legs and feet (Fig. 1A and 1B) The lesions were improved by colchicines 0.6 mg/day, hydroxyzine, and methylprednisolone 4 to 8 mg/day. Biopsy showed obliterative vasculopathy consistent with LV (Fig. 1C). A segmental limb pressure test with a bidirectional Doppler test showed normal blood pressures in all four extremities. She was intermittently treated with pentoxifylline and mupirocin ointment for skin lesions for three years. She was in good medical condition except for the skin lesions and had no experience of smoking. She was not taking oral contraceptives or suffering from migraine. She had one son and no history of spontaneous abortion.

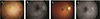

At presentation, her visual acuity was hand motion in the right eye and 20 / 20 in the left eye. Fundus examination of the right eye showed whitish edematous retina, a cherry-red spot, and narrowing and segmentation of retinal arteries suggesting acute CRAO (Fig. 2A) Laboratory test results, including rheumatological tests such as anti-nuclear antibody; anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies; anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; anti-DNA antibodies; rheumatoid factor; cryoglobulin; antithrombin activity; protein C and S activity; D-dimer; anti-beta2-glycoprotein; anticardiolipin antibody; lupus anticoagulant; prothrombin gene mutation; factor V Leiden gene mutation; and homocysteine, were all within normal limits except for slightly elevated C-reactive protein (0.62 mg/dL) and fibrinogen (425 mg/dL). The serology tests were positive for hepatitis B antigen while other serology tests were normal. Echocardiography and Holter monitoring showed normal findings.

She consented to receive intra-arterial thrombolysis after being informed of the possible risks and benefits of the intervention. Cerebral angiography showed severe focal vasospasm of the right internal carotid artery as soon as the catheter was placed (Fig. 3A), which was subsequently relieved by continuous intra-arterial infusion of nimodipine 5 mg. Selective angiography of the origin of the right ophthalmic artery showed no definite thrombus or steno-occlusive lesion within the ophthalmic artery (Fig. 3B). The ophthalmic artery was infused with a fibrinolytic agent (500,000 units of urokinase) until the maximal dose of fibrinolytics was reached as based on our protocol, but there was no visual improvement during the procedure. Seven hours after intra-arterial thrombolysis, retinal arterial perfusion on fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) did not improve (arm to retina time, 29 seconds; arteriovenous transit time: about 4 minutes) (Fig. 2B). FFA three days after intra-arterial thrombolysis showed nearly complete restoration of retinal arterial perfusion (arm to retina time, 17 seconds; arteriovenous transit time, about 30 seconds) with the exception of the macular area (no reflow phenomenon). Six weeks after thrombolysis, her visual acuity remained hand motion and fundus photography showed severe retinal atrophy in the macula and disc pallor (Fig. 2C). Retinal perfusion was restored sparing macula on FFA (Fig. 2D) and macular photoreceptor disruption was observed on optical coherence tomography.

The patient in our case was in the extremely low risk group for CRAO in that she was very young and without any known risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, renal disease, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular accidents, or smoking [10]. According to a population-based study, CRAO occurs more often in older persons, with a mean age of 61.9, but is relatively rare in young patients [11]. Approximately 75% of cases of retinal arterial obstruction (RAO) in patients over the age of 40 have findings suggestive of emboli originating from the carotid arteries [12]. However, young patients with RAO rarely have artheromatous vascular diseases, but rather have more diverse etiologic factors [13]. According to studies on RAO in young patients, one or more systemic or ocular findings were identified in 85% and 91% of patients under the ages of 30 and 40, respectively [13,14]. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that LV was associated with the pathogenic mechanism of CRAO in our case, as LV is known to cause occlusion of the dermal vessels by intravascular fibrin, segmental hyalinization, and endothelial proliferation [1]. To date, the pathogenesis of LV has not been fully elucidated. LV has been reported to be associated with hypercoagulable disorders and/or autoimmune diseases [1], such as hyperhomocysteinemia, activated protein C resistance, factor V Leiden mutation, elevated fibrinopeptide A levels, anticardiolipin antibodies, or defective release of tissue plasminogen activator [15-19]. To our knowledge, there have been no CRAO cases reported to be associated with LV.

As CRAO can be appropriately considered as a form of cerebrovascular lesion [20], our case may also be considered a variant of Sneddon's syndrome, which is characterized by generalized livedo reticularis and cerebrovascular lesion [21]. There have been 5 case reports of CRAO in Sneddon's syndrome, of which 3 were male and 2 were female, with an average age of 34.6 years (range, 18 to 50 years) [5-9]. Among them, antiphospholipid antibody was tested in 4 cases, out of which 3 were positive and 1 was negative [5-9]. Antiphospholipid antibodies have been found in up to 80% of individuals with Sneddon's syndrome [20]. Although there were no differences in clinical manifestations between the antibody-positive and negative groups [22], only the antiphospholipid antibody-positive patients could fulfill the diagnostic criteria for antiphospholipid antibody syndrome [23]. Therefore, our case is the second case of CRAO in Sneddon's syndrome not associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. In comparison with previously reported retinal artery occlusion in patients with Sneddon's syndrome, our case is distinguishable by the presence of skin ulceration and the lack of history of cerebrovascular accidents [5-8] as well as the absence of antiphospholipid antibodies [5,6,8]. In conclusion, acute CRAO can occur in association with LV in middle-aged female patients and may be an atypical manifestation of Sneddon's syndrome.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A,B) Physical examination of the patient showed itching and tender violaceous to dark erythematous non-elevated patches with central necrotic vesicles on the dorsum of both lower legs and feet. (C) The histopathology of the skin lesion showed perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltration in the dermis. Fibrin material was observed in the vessel lumen (arrow) and extravasated red blood cells were present. No leukocytoclasis observed (H&E, ×100).

Fig. 2

Fundus photography and fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) immediately after (A,B) and six weeks after (C,D) intra-arterial thrombolysis (IAT) therapy for acute central retinal artery occlusion. (A) The immediate post-IAT fundus photograph showed no change from the pre-IAT fundus photograph. (B) Early phase FFA still showed delayed retinal arterial filling and arteriovenous transit time. (C) Six weeks after thrombolysis, fundus photography showed severe atrophy of the macula and disc pallor. (D) The retinal arterial perfusion was restored except for the macular area on FFA.

Fig. 3

Right internal carotid angiography before the intra-arterial thrombolysis procedure. (A) Severe vasospasm (arrow) in the proximal cervical internal carotid artery was noted in response to catheter placement, which was relieved by intra-arterial nimodipine infusion (5 mg). (B) Selective angiography of the right ophthalmic artery showed no thrombus or steno-occlusive lesion in the ophthalmic artery.

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by the Translational Research Program (A111161) funded by the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea.

Notes

References

1. Khenifer S, Thomas L, Balme B, Dalle S. Livedoid vasculopathy: thrombotic or inflammatory disease? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010; 35:693–698.

2. Read RW, Chong LP, Rao NA. Occlusive retinal vasculitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000; 118:588–589.

3. Mirza S, Raghu Ram AR, Bowling BS, Nessim M. Central retinal artery occlusion and bilateral choroidal infarcts in Wegener's granulomatosis. Eye (Lond). 1999; 13(Pt 3a):374–376.

4. Warrasak S, Tapaneya-Olarn W, Euswas A, et al. Fibromuscular dysplasia: a rare cause of cilioretinal artery occlusion in childhood. Ophthalmology. 2000; 107:737–741.

5. Shimizu K, Numaga J, Takahashi M, Matsunaga T. A case of Sneddon syndrome. Nihon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1995; 99:104–108.

6. Jonas J, Kolble K, Volcker HE, Kalden JR. Central retinal artery occlusion in Sneddon's disease associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986; 102:37–40.

7. Pauranik A, Parwani S, Jain S. Simultaneous bilateral central retinal arterial occlusion in a patient with Sneddon syndrome: case history. Angiology. 1987; 38(2 Pt 1):158–163.

8. Alegre VA, Winkelmann RK, Gastineau DA. Cutaneous thrombosis, cerebrovascular thrombosis, and lupus anticoagulant--the Sneddon syndrome: report of 10 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1990; 29:45–49.

9. Rehany U, Kassif Y, Rumelt S. Sneddon's syndrome: neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations in a possible autosomal recessive pattern. Neurology. 1998; 51:1185–1187.

10. Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman MB. Retinal artery occlusion: associated systemic and ophthalmic abnormalities. Ophthalmology. 2009; 116:1928–1936.

11. Ivanisević M, Karelovic D. The incidence of central retinal artery occlusion in the district of Split, Croatia. Ophthalmologica. 2001; 215:245–246.

12. Kollarits CR, Lubow M, Hissong SL. Retinal strokes. I. Incidence of carotid atheromata. JAMA. 1972; 222:1273–1275.

13. Brown GC, Magargal LE, Shields JA, et al. Retinal arterial obstruction in children and young adults. Ophthalmology. 1981; 88:18–25.

14. Greven CM, Slusher MM, Weaver RG. Retinal arterial occlusions in young adults. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995; 120:776–783.

15. Calamia KT, Balabanova M, Perniciaro C, Walsh JS. Livedo (livedoid) vasculitis and the factor V Leiden mutation: additional evidence for abnormal coagulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002; 46:133–137.

16. McCalmont CS, McCalmont TH, Jorizzo JL, et al. Livedo vasculitis: vasculitis or thrombotic vasculopathy? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992; 17:4–8.

17. Klein KL, Pittelkow MR. Tissue plasminogen activator for treatment of livedoid vasculitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992; 67:923–933.

18. Acland KM, Darvay A, Wakelin SH, Russell-Jones R. Livedoid vasculitis: a manifestation of the antiphospholipid syndrome? Br J Dermatol. 1999; 140:131–135.

19. Grob JJ, Bonerandi JJ. Thrombotic skin disease as a marker of the anticardiolipin syndrome: livedo vasculitis and distal gangrene associated with abnormal serum antiphospholipid activity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989; 20:1063–1069.

20. Biousse V, Calvetti O, Bruce BB, Newman NJ. Thrombolysis for central retinal artery occlusion. J Neuroophthalmol. 2007; 27:215–230.

21. Sneddon IB. Cerebro-vascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965; 77:180–185.

22. Aladdin Y, Hamadeh M, Butcher K. The Sneddon syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2008; 65:834–835.

23. Asherson RA, Cervera R, de Groot PG, et al. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines. Lupus. 2003; 12:530–534.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download