Abstract

A 50-year-old woman, who had undergone extensive removal of conjunctiva on the right eye for cosmetic purposes at a local clinic 8 months prior to presentation, was referred for uncontrolled intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation (up to 38 mmHg) despite maximal medical treatment. The superior and inferior conjunctival and episcleral vessels were severely engorged and the nasal and temporal bulbar conjunctival areas were covered with an avascular epithelium. Gonioscopic examination revealed an open angle with Schlemm's canal filled with blood to 360 degrees in the right eye. Brain and orbital magnetic resonance imaging and angiography results were normal. With the maximum tolerable anti-glaucoma medications, the IOP gradually decreased to 25 mmHg over 4 months of treatment. Extensive removal of conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule, leaving bare sclera, may lead to an elevation of the episcleral venous pressure because intrascleral and episcleral veins may no longer drain properly due to a lack of connection to Tenon's capsule and the conjunctival vasculature. This rare case suggests one possible mechanism of secondary glaucoma following ocular surgery.

Episcleral venous pressure (EVP) has been reported to be elevated in patients with carotid cavernous sinus fistulae, thyroid ophthalmopathy, Sturge-Weber syndrome, other general venous static conditions, and, rarely, in the absence of any identifiable cause [1]. Elevated EVP increases intraocular pressure (IOP) because IOP is determined by the balance between aqueous production rates and the EVP [2-6]. Thus, the cause and extent of EVP elevation needs to be determined. We recently treated a patient with intractably elevated EVP and IOP after extensive removal of bulbar conjunctiva. A deficiency of conjunctival vasculature in this patient may have been the cause of the pathogenic EVP elevation, or may have at least aggravated the condition.

A 50-year-old Asian woman who had undergone conjunctival and Tenon's capsule removal surgery on the right eye for cosmetic purposes at a local clinic 8 months prior to presentation, was referred to our University-associated tertiary-care eye center due to uncontrolled elevated IOP. She did not have any other significant past medical or social history. She did not take any systemic medications. Before conjunctival removal surgery, she had complained of redness in the right eye for 3 years, although she did not have ocular pain or irritation. The left eye did not show redness. Before surgery, IOP measurement was performed at two different visits. Goldmann applanation tonometry revealed that IOPs were 19 and 13 mmHg at the first visit, and 19 and 12 mmHg at the second visit, in the right and left eye, respectively. The optic disc and visual field (VF) were apparently normal. Average retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness, determined by Stratus optical coherence tomography (OCT), revealed mild asymmetry, the average RNFL thickness was 91.77 microns in the right eye and 103.22 microns in the left (Fig. 1A).

Her prior surgery included extensive removal of nasal and temporal bulbar conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule on exposed areas of the sclera. Upper and lower triangular layers of conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule, from horizontal incisions at nasal and temporal canthal areas, were excised. The superior and inferior conjunctiva which were covered by the eyelid were not removed. The surgical area remained bare sclera and the sclera healed with thin overlying epithelium. After conjunctival removal surgery, the patient was treated with Fluorometholone (0.1%) for 2 months.

The IOP began to increase in the right eye 1 week after conjunctival removal surgery. The IOP ranged from 30 to 35 mmHg, despite prescription of maximum tolerated medications. An OCT scan performed 4 months postoperatively revealed reduction in average RNFL thickness in the right eye from 91.77 to 78.09 microns, while the left eye demonstrated minimal change, from 103.23 to 100.86 microns (Fig. 1B). The patient was then referred to our clinic.

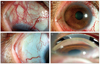

At first examination in our clinic, the IOP in the right eye was 38 mmHg with three anti-glaucoma medications (dorzolamide-timolol, latanoprost 0.005%, and brimonidine tartrate 0.15%). The superior and inferior conjunctival and episcleral vessels were severely engorged (Fig. 2A and 2B), and the nasal and temporal bulbar conjunctival areas were covered with an avascular epithelium, within which a few nasal and temporal episcleral vessels were also engorged (Fig. 2C). Gonioscopic examination revealed an open angle, with Schlemm's canal filled with blood to 360 degrees in the right eye (Fig. 2D). The left eye was normal. Ocular examination revealed no evidence of bruit, chemosis, proptosis, or extraocular muscle limitation, suggesting no apparent causes for EVP elevation in either eye. Brain and orbital magnetic resonance imaging and angiography results were normal. The VF was also normal 8 months after surgery.

We prescribed timolol 0.5%/brinzolamide 1% combination twice a day, apraclonidine 0.5% three times a day, travoprost 0.004% once a day, and oral acetazolamide (250 mg four times a day). After 4 months, the IOP gradually decreased to approximately 25 mmHg, and the oral acetazolamide was tapered. Current treatment includes three topical anti-glaucoma medications, and the IOP remains approximately 25 mmHg. We will consider surgical treatment if a VF defect develops.

EVP elevation is one cause of IOP elevation. EVP elevation may result from a carotid cavernous sinus fistula, thyroid ophthalmopathy, or Sturge-Weber syndrome. However, in some patients no definite cause of EVP elevation can be determined [1]. We suspect that the current patient had signs of mild EVP elevation in the right eye prior to surgery. There was evidence that the IOP in her right eye was relatively higher than the left (19 mmHg vs. 12-13 mmHg on two separate measurements): her right eye was red (perhaps attributable to episcleral venous engorgement) and the average RNFL thickness was relatively thinner in her right eye than in her left. These data may indicate that either chronic or mild IOP elevation, caused by a rise in EVP, and subsequent slight glaucomatous structural loss in the right eye, may have occurred prior to surgery.

Aqueous humor drainage is achieved principally by the conventional trabecular meshwork, which is connected to Schlemm's canal. Aqueous outflow drains from Schlemm's canal to the aqueous vein via collector channels, and then to the episcleral and conjunctival veins [5]. Thus, extensive removal of conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule layers may result in loss of the conjunctival veins that contribute to aqueous drainage. Therefore, in the present case, the aqueous humor, which had drained preoperatively through nasal and temporal conjunctival veins, along with the episcleral vein, was forced to exit through residual episcleral veins. Overloading of such veins with aqueous humor may aggravate any pre-existing elevation in EVP. Alternatively, the observed increase in IOP may be attributable to other causes, including postoperative inflammation or steroid use. However, no anterior chamber reaction occurred after surgery and immediate IOP elevation after surgery is not a typical response to steroid treatment. More importantly, the presence of blood in Schlemm's canal to all angles, and engorged superior and inferior episcleral vessels, are highly suggestive of EVP elevation.

In summary, extensive removal of limbus based conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule, leaving bare sclera, likely led to an elevation of the EVP because intrascleral and episcleral veins could no longer drain properly, due to the lack of connection to Tenon's capsule and the conjuctival vasculature. In a retrograde manner, the pressure in the collector channels and the IOP were increased in this eye. Although this particular eye could have been predisposed to such a reaction (signs of a mildly elevated EVP were retrospectively found to have been present prior to surgery), this rare case suggests one possible mechanism of secondary glaucoma following ocular surgery.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Optical coherence tomography retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) scans obtained (A) preoperatively, and (B) 4 months after surgery. Average RNFL thickness in the right eye fell from 91.77 microns to 78.09 microns.

Fig. 2

(A,B) Anterior segment examination of the right eye, demonstrating episcleral and conjunctival engorgement in the superior and inferior areas. (C) The temporal bulbar conjunctiva lacked conjunctival vessels and was covered with a thin epithelium, with few engorged episcleral vessels. (D) Gonioscopic examination demonstrated an open angle with blood in Schlemm's canal.

References

1. Rhee DJ, Gupta M, Moncavage MB, et al. Idiopathic elevated episcleral venous pressure and open-angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009. 93:231–234.

2. Ruiz-Ederra J, Verkman AS. Mouse model of sustained elevation in intraocular pressure produced by episcleral vein occlusion. Exp Eye Res. 2006. 82:879–884.

3. Shareef SR, Garcia-Valenzuela E, Salierno A, et al. Chronic ocular hypertension following episcleral venous occlusion in rats. Exp Eye Res. 1995. 61:379–382.

4. Urcola JH, Hernandez M, Vecino E. Three experimental glaucoma models in rats: comparison of the effects of intraocular pressure elevation on retinal ganglion cell size and death. Exp Eye Res. 2006. 83:429–437.

5. Bron AJ, Tripathi RC, Tripathi BJ, Wolff E. Wolff's anatomy of the eye and orbit. 1997. 8th ed. London: Chapman & Hall Medical;292–298.

6. Mittag TW, Danias J, Pohorenec G, et al. Retinal damage after 3 to 4 months of elevated intraocular pressure in a rat glaucoma model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000. 41:3451–3459.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download