Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate changes in anterior chamber depth (ACD) and angle width induced by phacoemulsification and intraocular lens (IOL) implantation in eyes with glaucoma, using anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT).

Methods

Eleven eyes of 11 patients with angle-closure glaucoma (ACG) and 12 eyes of 12 patients with open-angle glaucoma (OAG) underwent phacoemulsification and IOL implantation. Using AS-OCT, ACD and angle parameters were measured before and 2 days after surgery. Change in intraocular pressure (IOP) and number of ocular hypotensive drugs were evaluated.

Results

After surgery, central ACD and angle parameters increased significantly in eyes with glaucoma (p < 0.05). Prior to surgery, mean central ACD in the ACG group was approximately 1.0 mm smaller than that in the OAG group (p < 0.001). Post surgery, mean ACD of the ACG group was still significantly smaller than that of the OAG group. No significant differences were found in angle parameters between the ACG and OAG groups. In the ACG group, postoperative IOP at the final visit was significantly lower than preoperative IOP (p = 0.018) and there was no significant change in the number of ocular hypotensive medications used, although clinically, patients required fewer medications. In the OAG group, the IOP and number of ocular hypotensive drugs were almost unchanged after surgery.

Angle-closure glaucoma (ACG) and open-angle glaucoma (OAG) are thought to arise from different pathogeneses. ACG typically results from abnormal anatomy of the anterior segment of the eye, such as a narrow anterior chamber angle, a shallow anterior chamber depth, a thicker lens, a more anterior lens position, a small corneal diameter or a shorter axial length [1-4]. Lens position and size play a pivotal role in angle closure; therefore, lens extraction is a novel, efficient treatment protocol of acute and chronic ACG [5-9]. On the other hand, those with OAG appear to have a normal iridocorneal angle but the aqueous outflow is low. To better understand the pathophysiology of glaucoma and to apply such knowledge to clinical treatment, precise visualization and quantitative evaluation of angle configurations is essential.

Recently, anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) has been used for quantitative evaluation of anterior segment configurations. A number of studies that used AS-OCT have reported adequate angle configuration change after cataract extraction in normal eyes [10-12].

In this study, we compared changes in anterior chamber configurations in ACG- and OAG-eyes after phacoemulsification and posterior chamber intraocular lens (IOL) implantation. For a quantitative analysis of the anterior chamber configurations, we used AS-OCT. We also evaluated the influence of cataract surgery in controlling intraocular pressure (IOP) and the number of required ocular hypotensive medications in patients with ACG and OAG both pre- and post-surgery.

Twenty-three eyes of 23 patients participated in this study (11 eyes affected by ACG and 12 eyes affected by OAG). A total of 23 eyes underwent phacoemulsification and foldable IOL implantation from March 2008 to July 2009. Informed consent was obtained from all patients in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The local institutional review board approved the protocol.

All patients completed an ophthalmologic examination including best-corrected visual acuity and manifest refraction, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, Goldmann applanation tonometry, gonioscopy, and indirect ophthalmoscopy. The number of ocular hypotensive medications being taken by each patient was assessed prior to surgery.

Axial lengths were obtained using the Humphrey 820 model A-scan ultrasound unit (Humphrey Systems, Dublin, CA, USA). ACG and OAG patients were categorized based on recent diagnostic classifications of glaucoma [13]. In brief, ACG is defined as an eye with an occludable drainage angle and features indicating that trabecular obstruction by the peripheral iris has occurred, such as peripheral anterior synechia, elevated IOP, iris whirling, 'glaucomfleken' lens opacities or excessive pigment deposition on the trabecular surface, accompanied with glaucomatous optic disc changes. Eyes with a history of angle-closure attack and/or previous laser iridotomy were also included in the ACG group. The OAG was defined as an eye with an open angle, elevated IOP and glaucomatous optic neuropathy such as optic nerve head excavation or thinning of the neuroretinal rim and corresponding visual field defects.

One surgeon (PKH) performed all operations under topical anesthesia. In all but two eyes, a 2.75 mm clear corneal incision through a temporal approach was created; in two eyes, a 2.2 mm clear corneal incision was made. Through this incision, the continuous curvilinear capsulorrhexis measuring approximately 5.5 mm in the diameter was formed. The hydrodissection was followed by phacoemulsification of the nucleus and cortex aspiration. The lens capsule was inflated with an ophthalmic viscosurgical device (OVD) and the foldable IOL was placed in the capsular bag. The corneal wound was not sutured. There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications for any patients.

We performed AS-OCT (Visante; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA) on the eyes of both patient groups before surgery and 2 days after. One examiner obtained all images under identical lighting conditions. For the measurement, the pupil was undilated and the patient was asked to sit and fixate on an indicator in the AS-OCT. Images of the nasal and temporal angle quadrants (0° and 180° meridians) were captured until the centration and quality were enough to analyze (Fig. 1). IOP measurement using a Goldmann applanation tonometer and an assessment of the number of ocular hypotensive medications were performed every visit after surgery.

We selected the best images and analyzed them using custom software (Iridocorneal module, Carl Zeiss Meditec). Central anterior chamber depth (ACD), defined as the distance from the endothelium at the center of the cornea to the anterior pole of the lens or IOL, was an important parameter in the analysis. We calculated anterior chamber angle width in two ways: 1) anterior chamber angle (ACA) - the angle between the iris tangential line and that of the posterior corneal surface with its apex in the angle recess and 2) trabecular-iris angle (TIA) - the angle between the arms passing through a point on the trabecular meshwork 500 µm from the scleral spur and the point perpendicularly opposite on the iris. Anterior chamber angle width was also analyzed using standardized angle parameters after manual identification of the scleral spur: 1) angle-opening distance at 500 µm (AOD500) and AOD at 750 µm (AOD750) - distance of a perpendicular from the trabecular meshwork on the iris at a point 500 or 750 µm from the sclera spur and 2) trabecular-iris space area up to 500 µm (TISA500) or 750 µm (TISA750) - the area bounded by the corneal endothelium, trabecular meshwork and anterior iris surface out to a distance of 500 or 750 µm from the scleral spur.

All statistical analyses were performed using a chi-Square test, Mann-Whitney U-test or Wilcoxon's rank sum test. Age and axial length were adjusted for using the general linear model. All results were considered significant at p < 0.05, two-tailed.

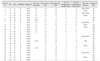

The mean age of patients was 69.4 ± 6.6 years. The mean follow-up period was 3.82 ± 4.51 months (range, 1 to 16 months) in the ACG group and 5.33 ± 2.93 months (range, 1 to 9 months) in the OAG group. Patient characteristics are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Three types of IOLs were used. No significant differences were found between the two groups with regard to age, gender, laterality, visual acuity, refractive errors, follow-up periods and preoperative IOP. Axial length was significantly longer in eyes with OAG than with ACG (p = 0.013).

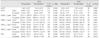

Table 3 shows the anterior chamber parameters before and after cataract surgery, and percentage change for each parameter after surgery of the two groups. Preoperative mean ACD of the ACG group was significantly less than that of the OAG group (p < 0.001). After surgery, ACD increased significantly after cataract surgery in both groups (p < 0.01) and the difference was greater in the ACG group (p < 0.001). The differences in ACD, between the two groups remained statistically significant after surgery, and postoperative ACD was smaller in the ACG group (p < 0.01). However, postoperative ACD did not remain significant after adjusting for age and axial length (p = 0.85), whereas preoperative ACD and changes in ACD remained significant (p < 0.001 and p = 0.002, respectively).

The ACA in the nasal and temporal quadrants in both the ACG and OAG groups increased significantly after surgery (p < 0.05). The ACA of the ACG group was significantly smaller than that of the OAG group before surgery. Postoperative ACA and the differences associated with the surgery, did not statistically differ between groups. After adjusting for age and axial length, preoperative ACA of both angles did not significantly differ between groups (p = 0.062 and p = 0.077, respectively). Other angle parameters that used the scleral spur as a reference point showed similar results. All angle parameters in the ACG and OAG patients increased significantly after the surgery (p < 0.01) (Table 3). Each of the angle parameters showed no significant differences between the ACG and OAG groups before and after surgery, except for preoperative AOD750 in the temporal quadrant (p = 0.037). After adjusting for age and axial length, all angle parameter changes did not significantly differ by group. Finally, there were no significant differences on any parameters in the nasal and temporal quadrants after surgery.

Preoperative and postoperative IOP and the number of ocular hypotensive medications needed to maintain a stable IOP were also assessed. In the ACG group, preoperative IOP was 17.00 ± 7.14 mmHg and postoperative IOP at two days after surgery decreased to 14.09 ± 4.81 mmHg. The IOP at one month postoperatively and the IOP at the final visit were 12.36 ± 2.94 mmHg and 12.18 ± 4.38 mmHg, respectively, which were significantly decreased compared to the preoperative IOP (p = 0.014 and p = 0.018, respectively). he IOP in the OAG group increased from 13.33 ± 3.37 mmHg to 15.00 ± 7.62 mmHg from pre-surgery to immediately post-surgery. However, the IOP after one month and the final IOP were 13.42 ± 3.26 mmHg and 13.42 ± 3.23 mmHg in OAG group, which were almost identical to the mean value prior to surgery (Fig. 2A). The number of ocular hypotensive medications needed decreased from 1.64 ± 1.86 to 0.82 ± 1.08, one month after surgery in the ACG group and was maintained at the final visit. The number of medications needed in the OAG group was 2.33 ± 1.07 preoperatively and 2.17 ± 1.53 at one month postoperatively, which was maintained at the final visit (Fig. 2B). These differences were not statistically significant.

In this study, we analyzed the change in anterior segment configuration after cataract extraction and posterior chamber IOL implantation in eyes with ACG and OAG using anterior segment OCT to quantitatively measure parameters. Our results showed that the ACD and ACA parameters significantly differed from pre- to post-surgery, which is consistent with findings from previous studies [5,10-12,14]. Compared to the OAG group, the ACG group had a smaller ACD before and after surgery. Preoperative ACD was 1.63 ± 0.23 mm in the ACG group and 2.62 ± 0.47 mm in the OAG group. Differences in ACD between the two groups were also consistent with findings of an earlier study [5].

The differences in the changes of the ACA between the ACG and OAG groups were 8.69° at the nasal and 8.76° at the temporal (mean 8.73°) quadrants before cataract surgery, and 3.12° at the nasal and 5.93° at the temporal (mean 4.53°) quadrants after surgery. Preoperative ACA was significantly smaller in the ACG group compared to the OAG group, whereas postoperative ACA did not differ between the two groups. Additionally, the change caused by cataract extraction did not significantly differ between the two groups. This result suggests that the lens factor may be an important pathological parameter in ACG. Although there are likely other factors that are also important. However, after adjusting for age and axial length, other parameters did not significantly differ between groups except for preoperative ACD and changes in ACD, suggesting that axial length may also be an important factor which influence to the anterior chamber configuration.

All angle parameters including the AOD, TISA and TIA significantly increased after surgery in both groups (p < 0.01). Percent change on these parameters was always smaller in the OAG versus ACG group. In the OAG group, the AOD and TISA increased by about 85% at the nasal quadrant and by 55% at the temporal quadrant. This result was consistent with the findings of a previous study [10]. Nolan et al. [10] studied 21 normal subjects using the AS-OCT before and after cataract extraction surgery. After the surgery, the AOD500 and TISA750 increased by about 80% at the nasal quadrant and about 55% at the temporal quadrant. Collectively, these results suggest that individuals with OAG likely have similar angle anatomy compared to normal subjects and that the effect of cataract surgery on angle anatomy was similar to that done in normal eyes [12]. In contrast, the AOD and TISA in the ACG group increased 112% (from 99% to 131%) after cataract surgery and showed no differences by quadrant in the present study. The percent increase did differ by quadrant in the OAG group, whereas it was identical in the ACG group. These differences may have been due to the small number of patients in the present study; however, other factors could have influenced these results. One other possible explanation is that the goniosynechiolysis of the angle, during surgery, in conjunction with the OVD and fluids via the temporal clear cornea, might have had differential quadrant effects.

In the ACG group, the IOP was reduced by 17% (2.91 mmHg) after surgery, whereas the IOP increased by 13% (1.67 mmHg) in the OAG group immediately postoperatively. There were two patients that had peak IOP in the OAG group and one of them was a steroid responder. The final IOP measured at the final visit decreased by 27% (4.64 mmHg) in ACG group and there were no changes in the OAG group. The final IOP was similar in the two study groups; however, the percent change was significantly different (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the change in the number of ocular hypotensive medications needed differed in the two groups (50% reduction in ACG group vs. 7% reduction in OAG group). Collectively, these results indicate that cataract surgery might cause more changes in terms of lowering the IOP and reducing the number of medications needed for treatment in those with ACG than those with OAG.

In this study, we used the AS-OCT to quantitatively measure the ACD and angle parameters. This technique provides high-resolution, cross-sectional images using non-contact methods. The AS-OCT shows good repeatability and reproducibility with low intra-observer and inter-observer variability [15-17]. Using this simple non-contact method, we were able to obtain immediate postoperative images two days after surgery. Several previous studies have measured change in angle configuration after surgery using the AS-OCT in normal eyes [10-12]. However, to determine whether cataract surgery is an effective treatment option for patients with glaucoma, angle configuration changes in eyes with glaucoma caused by cataract surgery should be evaluated. This is the first study to compare angle configuration changes between ACG and OAG patients using the AS-OCT.

Although this study makes several novel contributions, this study has several limitations. First, this study included a small number of patients to determine meaningful differences between those with ACG and OAG. The differences in angle parameters showed a tendency for cataract surgery to have a greater effect on the eyes in those with ACG versus OAG; however, these results were not statistically significant. Second, the follow-up period was short. We evaluated the preoperative and immediate postoperative angle configurations two days after surgery. Using AS-OCT, which is noninvasive and has high acceptability to patients, we were able to obtain immediate postoperative data without any problems. Few studies have been able to evaluate angle parameters in such a short time period after surgery; thus, we intended to evaluate parameters within this short time frame. Moreover, after non-complicated phacoemulsification using clear corneal incision, changes in postoperative anterior chamber configurations may be minimal after two days. However, it will be important to confirm the long-term effects of cataract surgery to the angle configuration for the treatment of glaucoma.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that the anterior chamber deepens and the angle widens after phacoemulsification and posterior chamber IOL implantation in eyes with glaucoma. These findings provide quantitative values of angle parameters using the AS-OCT. Additionally, the IOP and the number of ocular hypotensive medications needed for individuals with ACG versus OAG were reduced during the postoperative period. Our results suggest that cataract extraction might be considered as an effective treatment option for patients with ACG. Further study with a larger group of patients and with long-term follow up is necessary to confirm these results.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Anterior segment optical coherence tomography showed changes in the anterior chamber configuration induced by phacoemulsification and posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation in eyes with angle-closure glaucoma (ACG) and open-angle glaucoma (OAG). Preoperatively, the anterior chamber depth and angle width in eyes with ACG (left) were smaller than in the eyes with OAG (right). However, the anterior chamber depth and angle width were almost identical in eyes with ACG and OAG after cataract surgery. |

| Fig. 2Change in mean intraocular pressure (IOP) and the number of ocular hypotensive medications needed in the two groups, preoperatively and postoperatively. (A) For the angle-closure glaucoma (ACG) group, the IOP showed a tendency to decrease during the immediate postoperative period and the final IOP was significantly decreased compared to the preoperative IOP (*p < 0.05). In contrast, the IOP for the open-angle glaucoma (OAG) group showed no significant difference after cataract surgery. (B) The number of hypotensive medications was also decreased after surgery in the ACG group whereas it was almost identical in the OAG group. |

Table 1

Characteristics of patients

IOP = intraocular pressure; IOL = intraocular lens; ACG = angle-closure glaucoma; LI = laser iridotomy; DM = diabetes mellitus; HTN = hypertension; TLE = trabeculectomy; OAG = open-angle glaucoma; B = Biovue IOL (Oii, Ontario, CA, USA); IQ = Acrysof IQ IOL (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA); S = Acrysof SA60AT IOL (Alcon).

Table 2

Comparison of baseline characteristics between patients with open-angle glaucoma and angle-closure glaucoma

References

1. Congdon NG, Youlin Q, Quigley H, et al. Biometry and primary angle-closure glaucoma among Chinese, white, and black populations. Ophthalmology. 1997. 104:1489–1495.

2. Lee DA, Brubaker RF, Ilstrup DM. Anterior chamber dimensions in patients with narrow angles and angle-closure glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984. 102:46–50.

3. Marchini G, Pagliarusco A, Toscano A, et al. Ultrasound biomicroscopic and conventional ultrasonographic study of ocular dimensions in primary angle-closure glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1998. 105:2091–2098.

4. Lowe RF. Aetiology of the anatomical basis for primary angle-closure glaucoma. Biometrical comparisons between normal eyes and eyes with primary angle-closure glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1970. 54:161–169.

5. Hayashi K, Hayashi H, Nakao F, Hayashi F. Changes in anterior chamber angle width and depth after intraocular lens implantation in eyes with glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2000. 107:698–703.

6. Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Niziol LM, et al. Cataract extraction in the collaborative initial glaucoma treatment study: incidence, risk factors, and the effect of cataract progression and extraction on clinical and quality-of-life outcomes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006. 124:1694–1700.

7. Nonaka A, Kondo T, Kikuchi M, et al. Angle widening and alteration of ciliary process configuration after cataract surgery for primary angle closure. Ophthalmology. 2006. 113:437–441.

8. Ming Zhi Z, Lim AS, Yin Wong T. A pilot study of lens extraction in the management of acute primary angle-closure glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003. 135:534–536.

9. Foster PJ. The epidemiology of primary angle closure and associated glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Semin Ophthalmol. 2002. 17:50–58.

10. Nolan WP, See JL, Aung T, et al. Changes in angle configuration after phacoemulsification measured by anterior segment optical coherence tomography. J Glaucoma. 2008. 17:455–459.

11. Kucumen RB, Yenerel NM, Gorgun E, et al. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography measurement of anterior chamber depth and angle changes after phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008. 34:1694–1698.

12. Chang DH, Lee SC, Jin KH. Changes of anterior chamber depth and angle after cataract surgery measured by anterior segment OCT. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2008. 49:1443–1452.

13. Foster PJ, Buhrmann R, Quigley HA, Johnson GJ. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002. 86:238–242.

14. Dawczynski J, Koenigsdoerffer E, Augsten R, Strobel J. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography for evaluation of changes in anterior chamber angle and depth after intraocular lens implantation in eyes with glaucoma. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007. 17:363–367.

15. Muller M, Dahmen G, Porksen E, et al. Anterior chamber angle measurement with optical coherence tomography: intraobserver and interobserver variability. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006. 32:1803–1808.

16. Li H, Leung CK, Cheung CY, et al. Repeatability and reproducibility of anterior chamber angle measurement with anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007. 91:1490–1492.

17. Radhakrishnan S, See J, Smith SD, et al. Reproducibility of anterior chamber angle measurements obtained with anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007. 48:3683–3688.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download