Abstract

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) is a rare congenital neurocutaneous disorder that causes congenital glaucoma. Previous experiences have shown that drainage procedures are often required to control associated glaucoma. The conventional surgical approach in trabeculectomy carries a significant risk of intraoperative expulsive hemorrhage. Here, we describe a modified approach of the conventional trabeculectomy technique, which may lower the risk of expulsive hemorrhage. A viscoelastic device was employed to maintain a steady intraocular pressure throughout the procedure. Details of the surgical technique and material used are described. One patient with congenital glaucoma associated with SWS underwent a successful trabeculectomy using the modified technique. Postoperative intraocular pressure was successfully reduced and no intraoperative complications occurred. We describe a successful case of trabeculectomy in a SWS case where a modified technique was applied.

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) is a relatively rare neurocutaneous disorder that can cause congenital glaucoma. Glaucoma, which is thought to be secondary to the increased episcleral venous pressure, has a reported prevalence of 30% to 71% in all patients with SWS [1,2]. Many surgical techniques have been described [1-5]. Since the etiology lies in the increased episcleral venous pressure, some advocate filtrating surgeries over other methods [2,3]. Previous experiences with trabeculectomy have shown good results but carry a risk of expulsive haemorrhage or massive choroidal effusion [1,2]. We describe a modified surgical technique designed to reduce the risk of trabeculectomy in a single case of congenital glaucoma secondary to SWS.

Our patient was first seen at 2-weeks old when he was referred for suspected right sided SWS and congenital glaucoma. He was born at 37 weeks and 1 day gestation. Delivery was spontaneous and uncomplicated. Prenatal and family histories were both unremarkable. Right facial hemangioma was noted at birth (Fig. 1). Systematically, he was healthy. Initial intraocular pressure (IOP) was 38 mmHg and 20 mmHg in the right and left eye, respectively, and was measured using the Perkins tonometer (Haag-Streit, Bern, Switzerland) under sedation with chloral hydrate. All IOPs mentioned here were measured with the Perkins tonometer. Bulphthalmos and corneal edema were noted in the right eye. An ultrasound B-scan was done to rule out choroidal lesions. The final diagnosis was right SWS with congenital glaucoma. Topical anti-glaucoma drops were tried for 2 weeks. First timoptol, then brinzolamide, and then lantanoprost were added to the treatment due to the suboptimal control. A more detailed examination under anesthesia (EUA) was planned. The parents agreed that glaucoma surgery could be performed should it be deemed necessary during the EUA.

Despite the use of topical anti-glaucoma medication, at the first EUA at 3-weeks of age, the IOPs were 14 mmHg and 6 mmHg in the right and left eye, respectively. Although sevoflurane was used on induction, the marked difference in the IOP between the two eyes hints that the IOP in the right eye was abnormal. Bulphthalmos and corneal edema persisted. The operation was performed by an experienced glaucoma surgeon (NSY). A corneal traction suture with 6-0 Vicryl was put in place to enhance exposure. Paracentesis was created with a 15-degree slit knife (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) in the 9 o'clock position. A fornix-based conjunctival flap was created in the superotemporal quadrant and haemostasis was achieved with wet-field cautery; all prominent episcleral and scleral vessels within the operative site were cauterized (Fig. 2). A superficial rectangular scleral flap, half of the estimated total scleral thickness, measuring 3 mm in width and 2 mm in length from the limbus, was created with a 15-degree slit knife and a 55-degree crescent knife (Beaver; Becton Dickinson Surgical Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The flap was dissected forward into a clear cornea for at least 0.5 mm. Mitomycin C 0.4 mg/mL was applied with a cellulose sponge placed both below the scleral flap and in the subconjunctival space on top of the scleral flap. The exposure time was 4 minutes, followed by irrigation with a balanced salt solution.

Before creating the inner window, 0.1 mL 1% acetycholine (Miochol CIBA Vision, Duluth, GA, USA) was injected intracamerally to constrict the pupil. Sodium hyaluronate 1% (Healon; AMO Inc., Abbott Park, IL, USA) was injected to fill the anterior chamber (AC) (Fig. 2). This was followed by creating an inner window with a Slit-knife and Kelly punch. The Healon injected a priori prevented the eye from experiencing a sudden drop in pressure. Peripheral iridectomy was performed with Vannas scissors (Katena Products Inc., Denville, NJ, USA). The superficial scleral flap was closed with 10-0 nylon at one corner and two releasable sutures, one at the other corner and one in between the other two stitches. Egress of aqueous humour through the guarded fistula was checked to ensure that there was no over-drainage and the conjunctiva was closed with 8-0 Vicryl. The remaining Healon was not removed from the anterior chamber. The eye was patched with an antibiotic and steroid ointment overnight, followed by topical antibiotic and steroid treatment the next morning.

When examined under sedation with chloral hydrate on post-operative day 1, the IOP was 15 mmHg and had a diffuse bleb. The wound was clear and the anterior chamber was well formed. Removal of the releasable sutures was done during the second EUA session on post-operative day 11. The post-operative IOP trend is shown in Fig. 3. The patient made a good recovery and the IOP remained low without the further use of anti-glaucoma drops. Two further sessions of EUA were performed; the findings of which are shown in Table 1. The patient's progress at 1-year old is shown in Fig. 1D.

Different prophylactic techniques have been proposed to lower the risk of choroidal effusion or hemorrhage during trabeculectomy in SWS. These include: replacing the flap quickly, pre-placed posterior sclerostomies, prophylactic laser photocoagulation, prophylactic radiotherapy and cauterization of the anterior episcleral vascular anomalies [3,6]. Although the risk of complications is now relatively low, it remains possible, and has potentially dreadful consequences [1-3,7].

With the injection of Healon into the AC prior to penetrating the inner window, any sudden changes in the IOP can be avoided. With Healon in-situ, the AC depth can also be maintained both intra- and post-operatively, which avoids complications associated with a flat AC. We did not experience any difficulties in estimating the aqueous flow rate, even with viscoelastics in the AC. This is because the viscoelastics did not fully fill the AC and there are channels for the aqueous humour to reach the inner window. As demonstrated by Lane et al. [8], the low disturbance to outflow ability due to the use of Healon facilitated the aqueous outflow assessment. Another advantage is that most surgeons are familiar with Healon and it is widely available in most parts of the world.

In our case, after successful trabeculectomy, the IOP was significantly lowered and EUA showed a reverse in bulphthalmos (Table 1). The axial length in the right eye was temporarily shortened, which is in accordance with other findings that damage due to congenital glaucoma early in life can be reversed [9].

The main limitation of this surgical technique is that we are only able to describe the experience of one case, which also reflects the rare occurrence of the disease.

We described a modified surgical technique for trabeculectomy in SWS. This system lowers the risk of intraoperative expulsive hemorrhage.

Figures and Tables

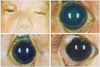

Fig. 1

(A) Clinical photo showing right facial haemangioma, characteristic of Sturge-Weber syndrome. (B) Right eye before primary operation showing features of bulphthalmos. (C) Normal left eye before the primary operation. (D) Operated eye one-year after operation, showing a well formed bleb superiorly.

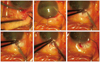

Fig. 2

Intraoperative photos. (A) Cauterisation of prominent episcleral vessels. (B) Injection of viscoelastics prior to anterior chamber penetration. (C) Appearance immediately prior to creating the inner window with slit knife. (D) Appearance of the inner window immediately after penetration with slit knife. Picture shows only a trace amount of viscoelastic egress from the anterior chamber. (E) Enlargement of inner window with a Kelly punch. (F) Testing aqueous outflow with the releasable suture tied.

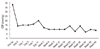

Fig. 3

Post-operative intraocular pressure trend in the right eye. The intraocular pressure (IOP) decreased significantly after the primary trabeculectomy. Although there was a surge in the second week post-operatively, the IOP decreased to a lower level after the removal of the releasable suture on post-operative day 11. Pre-op = pre-operative.

References

1. Iwach AG, Hoskins HD Jr, Hetherington J Jr, Shaffer RN. Analysis of surgical and medical management of glaucoma in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1990. 97:904–909.

2. Keverline PO, Hiles DA. Trabeculectomy for adolescent onset glaucoma in the Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol. 1976. 13:144–148.

3. Bellows AR, Chylack LT Jr, Epstein DL, Hutchinson BT. Choroidal effusion during glaucoma surgery in patients with prominent episcleral vessels. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979. 97:493–497.

4. Ali MA, Fahmy IA, Spaeth GL. Trabeculectomy for glaucoma associated with Sturge-Weber syndrome. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990. 21:352–355.

5. Audren F, Abitbol O, Dureau P, et al. Non-penetrating deep sclerectomy for glaucoma associated with Sturge-Weber syndrome. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006. 84:656–660.

6. Taylor DM. Expulsive hemorrhage. Am J Ophthalmol. 1974. 78:961–966.

7. Eibschitz-Tsimhoni M, Lichter PR, Del Monte MA, et al. Assessing the need for posterior sclerotomy at the time of filtering surgery in patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2003. 110:1361–1363.

8. Lane D, Motolko M, Yan DB, Ethier CR. Effect of Healon and Viscoat on outflow facility in human cadaver eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000. 26:277–281.

9. Wu SC, Huang SC, Kuo CL, et al. Reversal of optic disc cupping after trabeculotomy in primary congenital glaucoma. Can J Ophthalmol. 2002. 37:337–341.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download