Abstract

Phialemonium keratitis is a very rare case and we encountered a case of keratitis caused by Phialemonium obovatum (P. obovatum) after penetrating injury to the cornea. This is the first case report in the existing literature. A 54-year-old male was referred to us after a penetration injury, and prompt primary closure was performed. Two weeks after surgery, an epithelial defect and stromal melting were observed near the laceration site. P. obovatum was identified, and then identified again on repeated cultures. Subsequently, Natacin was administered every two hours. Amniotic membrane transplantation was performed due to a persistent epithelial defect and impending corneal perforation. Three weeks after amniotic membrane transplantation, the epithelial defect had completely healed, but the cornea had turned opaque. Six months after amniotic membrane transplantation, visual acuity was light perception only, and corneal thinning and diffuse corneal opacification remained opaque. Six months after amniotic membrane transplantation, visual acuity was light perception only, and corneal thinning and diffuse corneal opacification remained.

Members of the Phialemonium genus are dematiaceous fungi, which are known as causative fungi for opportunistic infection in immunocompromised hosts. The fungus is isolated from soil, air, water, or sewage. In very rare cases, it has been reported to be a cause of invasive disease [1-5]. We experienced a case in which keratitis developed during the monitoring of the clinical course after the primary closure of corneal laceration. In cultures of samples obtained from the corresponding patient, Phialemonium obovatum (P. obovatum) was identified, although it has not ever been reported to be the causative fungus of infectious ocular disease.

A 54-year-old man suffered injury during road construction when a nail fragment became imbedded in his left eye. He was referred to us by a local clinic for further evaluation and treatment. At the time of admission, his visual acuity was 0.8 in the right eye and hand motion only (HM) in the left eye. Slit lamp examination revealed a full-thickness corneal laceration 6.5 mm in size spanning from the 4 o'clock to the 7 o'clock position near the corneal limbus. A part of the swollen lens was anteriorly displaced, and hyphema was present. The patient was treated by primary closure of the lacerated cornea. However, the lens surgery was postponed by a couple of weeks until the decrease of corneal edema. He had a one-year history of hypertension, and he had been taking oral antihypertensives. He had no history of diabetes. However, at the time of admission, his serum glucose was 491 mg/dL and other laboratory findings were unremarkable. There was no history of other systemic disease. On postoperative day one, the patient's visual acuity was HM, and the suture site was clear. A small amount of viscoelastics materials remained in the anterior chamber, along with some floating vitreous fibers (Fig. 1). The lens surgery was postponed due to the corneal edema. He was discharged a week after the primary suture. There was no remarkable change during admission and first follow up after primary closure. On his second visit at approximately two weeks after surgery, the patient was noted to have an epithelial defect and subepithelial and stromal cell infiltrates at the laceration site. The patient complained that ocular discomfort and mild pain had increased 3 days previously. However, KOH smear and Gram stain were negative. We subjected the sample to bacterial and fungal culture. Meanwhile, the corneal cellular infiltrate and the corneal epithelial defect progressed. The cellular infiltrate was ring-shaped (Fig. 2), which was suggestive of various possible causes of keratitis such as fungus, pseudomonas, acanthameba, immune reaction, or toxic keratitis. It had a bizarre course of ulcer which started from the clear wound after more than 10 days under the levofloxacin eye drop instillation. The smear tests were negative for bacteria and fungi, and therefore, the patient was first thought to have an immune reaction or unidentified bacterial keratitis. The Pred-Forte (prednisolone acetate 1%; Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA) dose was therefore increased and applied to the eye in combination with Vigamox (moxifloxacin hydrochloride 0.5%; Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) at two-hour intervals. Nevertheless, the patient's symptoms did not improve. By approximately three weeks after surgery, the infiltration involved an extensive area of the cornea, the symptoms had worsened, and stromal melting had developed. The anterior chamber was no longer visible due to the corneal haze. Approximately 10 days after culture specimen inoculation, P. obovatum was cultured in Sabouraud-Dextrose agar (Figs. 3 and 4) and identified with a cotton-blue stain in microscopy. Natacin (Natamycin, Alcon) was applied to the eye every two hours. Thereafter, the corneal inflammation remained stable, and the cornea itself underwent minimal change. A week later, the frequency of antifungal eye drops was decreased to four times a day. However, corneal thinning and a persistent epithelial defect were noted in the central cornea, leading to the need for permanent amniotic membrane transplantation (P-AMT) and temporary amniotic membrane transplantation (T-AMT). During amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT), microbiology specimens were taken and cultured again and again showed P. obovatum. Approximately three weeks after the AMT was performed, the P-AMT was dehisced except for the periphery. The corneal stroma were almost completely opacified, a small epithelial defect remained in the periphery, and there was new vessel growth into the peripheral cornea. Approximately seven weeks after the AMT, visual acuity was HM, and the cornea was completely opacified. Corneal transplantation and lens extraction were recommended due to the persistent diffuse corneal opacity and previous lens damage (Fig. 5), but the patient refused it due to financial constraints.

Fungal keratitis may occur secondary to trauma, and its incidence is increased by the use of steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. It commonly occurs in subtropical rural areas in persons engaged in agriculture or in those with compromised immunity [6]. The epidemiology is dependent on the geographic area, however the most common causative organism worldwide is Aspergillus [7]. Hahn et al. [8] reported in the results of a multicenter study that Fusarium species were the most common causative strain (29.0%) in Korea.

The Phialemonium genus is intermediate in form between Acremonium and Phialophora. It was first described by Gams and McGinnis in 1983 [1]. Based on the degree of pigmentation and its conidial shape, it is classified into three types, Phialemonium curvatum (P. curvatum), P. obovatum, and Phialemonium dimorphosporum [1]. P. obovatum forms white to pale yellow or greenish colonies that initially produce green diffusible pigment and later produce black pigment at the colony center. In light microscopy, the conidial shape has an obovate form [1,9]. In the past 20 years, 16 cases of Phialemonium genus-induced infections have been reported and three of these infections were intraocular P. curvatum infections [1-5]. No ocular P. obovatum infections have been reported.

In the current case, the keratitis had a bizarre clinical course which started more than 10 days after surgery and became progressively worse. The smear tests showed negative results despite the intrastromal cell infiltration showing a ring-shaped pattern. These patterns led to a misdiagnosis of immune-mediated response. The frequency of steroid eye drop inoculation was increased, and the clinical course was followed closely. However, the patient's symptoms did not improve. The delayed diagnosis and the steroid application might have played important roles in the progression of the disease. Fungal keratitis is a corneal infection that is difficult to treat without proper diagnosis. The fungus invades the deep stroma, and thus, it cannot be easily cultured in many cases. Furthermore, fungus identification is often difficult to perform on KOH smears or cultures. There are also instances in which the toxic effects of eye drops cannot be differentiated from the inflammatory process seen during keratitis recovery [10]. After the culture results were revealed, natamycin inoculation was initiated for the treatment of fungal keratitis. Natacin is the first-line choice for treatment of fungal keratitis because of its broad spectrum activity and low toxicity. However, corneal thinning developed as a result of the delayed treatment, and AMT was required. Early diagnosis allows for the administration of appropriate eye drops and surgical treatment, if necessary. Delayed diagnosis can lead to a poor prognosis.

Fungal keratitis may develop in immunecompromised hosts, including those with diabetes [8]. The current patient had a blood glucose level of 491 mg/dL at the time of admission. The patient was not aware that his blood glucose level was high, and he had not been taking any medications for blood glucose control. It is probable that his hyperglycemia had been present for a long time. This might have increased his risk for developing fungal keratitis.

AMT has been effectively used in the treatment of various ocular surface diseases [11,12]. In the current case, the corneal epithelial defect and corneal thinning persisted despite the use of antifungal eye drops and preservative-free artificial tears. Therefore, the patient was managed through P-AMT and T-AMT. This suppressed the inflammation, leading to the healing of the persistent epithelial defect.

Phialemonium infections have been only rarely reported. To date, two reports have described three cases of endogenous endophthalmitis due to P. curvatum inoculated through intrapenile injection. Our patient denied a history of injection. To our knowledge, no case of ocular P. obovatum infection has been reported in the literature. Therefore, we report a case of fungal keratitis due to P. obovatum along with a review of the literature.

Figures and Tables

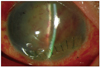

Fig. 1

Slit lamp photograph of the first day after operation showing a clear suture wound with blood coagulum in the anterior chamber and slightly displaced and swollen lens.

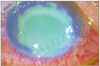

Fig. 2

Bluelight slit lamp photograph with fluorescein dye stain 2 weeks after primary suture of the lacerated cornea showed a large size epithelial defect and ring-shaped diffuse subepithelial and stromal inflammatory cell infiltration with stromal melting.

Fig. 3

Direct inoculation of the corneal scrapping specimen showed a broadly spreading grayish color and slightly fuzzy colonies with dark centers after 7 days of incubation at 25℃ on a blood agar plate.

Notes

References

1. Gams W, McGinnis MR. Phialemonium, a new anamorph genus intermediate between Phialophora and Acremonium. Mycologia. 1983. 75:977–987.

2. Heins-Vaccari EM, Machado CM, Saboya RS, et al. Phialemonium curvatum infection after bone marrow transplantation. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2001. 43:163–166.

3. Proia LA, Hayden MK, Kammeyer PL, et al. Phialemonium: an emerging mold pathogen that caused 4 cases of hemodialysis-associated endovascular infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004. 39:373–379.

4. Zayit-Soudry S, Neudorfer M, Barak A, et al. Endogenous Phialemonium curvatum endophthalmitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005. 140:755–757.

5. Weinberger M, Mahrshak I, Keller N, et al. Isolated endogenous endophthalmitis due to a sporodochial-forming Phialemonium curvatum acquired through intracavernous autoinjections. Med Mycol. 2006. 44:253–259.

6. Sundaram BM, Badrinath S, Subramanian S. Studies on mycotic keratitis. Mycoses. 1989. 32:568–572.

7. Tanure MA, Cohen EJ, Sudesh S, et al. Spectrum of fungal keratitis at Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Cornea. 2000. 19:307–312.

8. Hahn YH, Lee DJ, Kim MS, et al. Epidemiology of fungal keratitis in Korea: a multi-center study. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2000. 41:1499–1508.

9. Dixon DM, Polak-Wyss A. The medically important dematiaceous fungi and their identification. Mycoses. 1991. 34:1–18.

10. Foster CS, Lass JH, Moran-Wallace K, Giovanoni R. Ocular toxicity of topical antifungal agents. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981. 99:1081–1084.

11. Tseng SC, Prabhasawat P, Barton K, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation with or without limbal allografts for corneal surface reconstruction in patients with limbal stem cell deficiency. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998. 116:431–441.

12. Chun DH, Jeon SL, Lee JY, Choi TH. The effect of amniotic membrane transplantation on corneal epithelial cell proliferation. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2002. 43:1746–1757.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download