Abstract

A 75-year-old female was transferred to our clinic three days after uneventful phacoemulsification with intraocular lens (IOL) implantation in the right eye that had been carried out at a local clinic. Under the diagnosis of postoperative endophthalmitis, the patient underwent pars plans vitrectomy, IOL explantation, silicone oil tamponade, and intravitreal antibiotic injection. Even after the procedure, the patient's condition was further aggravated, and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli were identified on bacterial identification test. Although meropenem was applied locally and systemically, the patient had no-light perception visual acuity.

Infectious endophthalmitis after cataract surgery is the most devastating postoperative complication, but it has a better prognosis than other nosocomial infectious endophthalmitis variants. This distinction is likely because infectious endophthalmitis after cataract surgery is an infection that results from a less virulent organism [1,2]. Unlike other nosocomial infections, causative bacteria following cataract surgery commonly originate from the normal flora of patients [1]. In recent years, however, new resistant bacterial strains have been identified. Their scope is also expected to be extended to the field of ophthalmology [3]. We experienced a case of postoperative endophthalmitis occurring due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli (E. coli), which was first identified in 1983 [4,5]. Here, we report our case with a review of current literature.

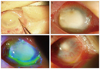

A 75-year-old woman underwent uneventful phacoemulsification with intraocular lens (IOL) implantation for the cataract occurring in the right eye at a local clinic. From day 1 on, the patient complained of ocular pain. On day 3, the patient's symptoms were aggravated, and her visual acuity had decreased; the patient was transferred to our clinic. At the time of admission, the patient had light perception. Upon slit lamp examination, the patient was observed to have severe conjunctival congestion, edema and infiltration over the cornea, hypopyon of 5 mm in height, and a thickened inflammatory fibrous membrane within the anterior chamber (Fig. 1A). We also observed wound dehiscence and severe corneal stromal melting at the site of the incision. At the time of admission, the patient underwent pars plana vitrectomy, IOL explantation and silicone oil tamponade. Aqueous humor and vitreous samples were aspirated to identify the causative organism prior to the main surgery. Additionally, the patient received intravitreal injections of vancomycin (1 mg/0.1 mL; Hanomycin, Samjim pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea) and ceftazidime (2 mg/0.1 mL; Fortum, GlaxoSmithKline, Uxbridge, UK) at the end of the procedure before the site was sutured. At the time of surgery, the pus that had spread over the retina's surface was removed with a flute needle, but some pus remained because it was strongly adhered. Due to severe infiltrations of the cornea and the presence of fine inflammatory substances on the surface of the IOL, the fundus could not be well observed. It was possible that the IOL was contaminated, so the IOL and the lens capsule were both removed. Postoperatively, the patient received systemic antibiotics, levofloxacin 500 mg intravenous injection qd (Cravit; Daiichi Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), and levofloxacin eye drops (Cravit; Santen Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan) at 2-hour intervals. On postoperative day 2, silicone oil leaked from the site of corneal wound, which had been sutured using 10-0 nylon. To resolve the leakage, this site was sutured again. Due to further progression of corneal melting on postoperative day 3, there was a multiple pin-point leakage of silicone oil in the overall area of the cornea. On organism identification test of the anterior chamber and vitreous, we identified that ESBL-producing E. coli had an extensive range of resistance to penicillins, cephalosporins, aminoglycosides and levofloxacin. Therefore, levofloxacin therapy was discontinued. A subtenon injection of meropenem (Meropen; Yuhan Co., Seoul, Korea), a carbapenem antibiotic, was administered at a dosage of 50 mg/cc concomitantly with eye drops at the same concentration each hour. A 120-degree periotomy was done to allow good penetration of the antibiotics. Intravenous injection of meropenem 500 mg bid was also administered. From postoperative day 6 the silicone leakage decreased significantly. After postoperative day 10, epithelialization was initiated from the corneal limbus. Hyaluronic acid eyedrops were inoculated at two-hour intervals. On postoperative day 13 (Fig. 1B and 1C), stromal lysis of the cornea decreased. New blood vessels began to grow from the peripheral cornea. Systemic antibiotics were used for 3 weeks. Meropenem eye drops were continued for 2 months. By postoperative month 2, inflammation had decreased. However, there were still findings suggestive of conjunctivalization of the corneal surface and the phthisis bulbi (Fig. 1D). The patient had no light perception visual acuity.

Intraocular infections occurring after cataract surgery are serious postoperative complications for which intraocular injections of sensitive antibiotics are mandatory in the early stages. Based on the characteristics of intraocular infection, a very urgent matter, a broad-spectrum antibiotic should be initiated without waiting for accurate identification of bacterial strains. However, ESBL-producing E. coli are bacteria that cannot be treated with conventional antibiotics. This type of E. coli typically produces a poor prognosis. ESBL-producing E. coli were first identified in 1983 [4,5]; ESBL is resistant to penicillin as well as the 1st, 2nd and 3rd generation cephalosporin antibiotics. There are also many cases in which ESBL-producing E. coli show a resistance to aminoglycoside and fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Accordingly, these bacterial strains produce a lower degree of treatment effects than do other drugs. Furthermore, the reliability of antibacterial sensitivity tests has also been reported to be relatively lower for ESBL-producing E. coli strains.

For an intraocular injection of antibiotics, vancomycin combined with ceftazidime or amikacin is commonly used [1,2,6]. Vancomycin and ceftazidime cover Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, respectively. At present, the manifestation and distribution of resistant bacterial strains is common. To treat intraocular infections, however, the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study injection regimen that was established in 1995 is still in use. This practice is likely because most cases of postoperative intraocular infections arise from Gram-positive bacteria, and these cases can sufficiently be covered by vancomycin [6]. However, Gram-negative bacterial strains show a higher degree of virulence as compared with Gram-positive ones [1,2]. Poor prognoses usually only result when patients do not receive intraocular injections of appropriate antibiotics in a timely manner. Currently, ceftazidime is insufficient. Further studies are warranted to determine the safest and most efficacious doses of antibiotics for intraocular injection. The safety of intravitreal dose of imipenem, one of the carbapenem antibiotics, has been demonstrated in rabbits [7]. These findings have not been verified in clinical studies. It has also been reported that an intravenous injection of both imipenem and meropenem reached a concentration exceeding the intraocular minimum inhibitory concentration [8,9]. However, no studies found that the above intravenous injection showed better outcomes than an intraocular injection of antibiotics. Also in our case, an intraocular injection was not attempted because its safety has not been established, and the patient's visual acuity still included light perception at that time. Considering that the intraocular status was promptly aggravated postoperatively, we presumed that an intraocular injection of meropenem after bacterial identification would not be effective in improving the visual acuity.

In the current case, we synchronously applied silicone oil with the expectation of a bacteriocidal effect. Conversely, we presumed that silicone oil pushed the pus into the eyeball's wall, which caused corneal melting. A demonstrated effect of silicone oil on the intraocular infection is based on the observation that an intraocular infection follows trauma [1]. The preventive effects against retinal detachment rather than the bacteriocidal effect of silicone oil would be a plausible explanation. Further studies are therefore warranted to examine the effects and side effects of silicone oil in cases with postoperative infections. We experienced a case of postoperative endophthalmitis that occurred due to ESBL-producing E. coli and reported our case with a review of the current literature.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1External ocular surface photography. (A) In the operating room, severe corneal stromal melting and infiltration was observed before surgery. (B) On postoperative day 13, the stromal lysis of the cornea decreased, and neovascularization from the peripheral cornea was noted. (C) On postoperative day 13, corneal epithelialization was observed from the limbus using a fluorescein stain. (D) On postoperative month 2, almost all the corneal surface was conjunctivalized. |

Notes

References

1. Meredith TA. Ryan SJ, Wilkinson CP, editors. Vitrectomy for infectious endophthalmitis. Retina. Vol. 3. Surgical retina. 2006. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Mosby;2255–2276.

2. Microbiologic factors and visual outcome in the endophthalmitis vitrectomy study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996. 122:830–846.

3. Major JC Jr, Engelbert M, Flynn HW Jr, et al. Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis: antibiotic susceptibilities, methicillin resistance, and clinical outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010. 149:278–283.e1.

4. Knothe H, Shah P, Krcmery V, et al. Transferable resistance to cefotaxime, cefoxitin, cefamandole and cefuroxime in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Serratia marcescens. Infection. 1983. 11:315–317.

5. Philippon A, Labia R, Jacoby G. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989. 33:1131–1136.

6. Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group. Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study: a randomized trial of immediate vitrectomy and of intravenous antibiotics for the treatment of postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995. 113:1479–1496.

7. Loewenstein A, Zemel E, Lazar M, Perlman I. Drug-induced retinal toxicity in albino rabbits: the effects of imipenem and aztreonam. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993. 34:3466–3476.

8. Axelrod JL, Newton JC, Klein RM, et al. Penetration of imipenem into human aqueous and vitreous humor. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987. 104:649–653.

9. Schauersberger J, Amon M, Wedrich A, et al. Penetration and decay of meropenem into the human aqueous humor and vitreous. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1999. 15:439–445.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download