Abstract

A 43-year-old man developed decreased vision in the right eye that had persisted for seven years. Under slit lamp examination, corneal clouding was noted with normal endothelium and ocular structure. From the clinical evidence, we suspected that the patient had congenital hereditary stromal dystrophy (CHSD). He and his family underwent a genetic analysis. Penetrating keratoplasty was conducted, and the corneal button was investigated for histopathologic confirmation via both light and electron microscopy. The histopathologic results revealed mildly loosened stromal structures, which exhibited an almost normal arrangement and differed slightly from the previous findings of CHSD cases. With regard to the genetic aspects, the patient and his mother harbored a novel point mutation of the decorin gene. This genetic mutation is also distinct from previously described deletion mutations of the decorin gene. This case involved delayed penetration of mild clinical symptoms with the histological feature of a loosened fiber arrangement in the corneal stroma. We concluded that this condition was a mild form of CHSD. However, from another perspective, this case could be considered as "decorin gene-associated corneal dystrophy," which is distinct from CHSD. Further evaluation will be required for appropriate clinical, histopathologic and genetic approaches for such cases.

Congenital hereditary stromal dystrophy (CHSD) of the cornea is a rare disease inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Minute stromal opacity of the cornea results in a gradual decrease in vision; nevertheless, this disorder is considered to be unrelated to abnormal architecture and function of endothelial cells. Previous reports [1,2] of CHSD have involved a deletion of the decorin gene (c.941delC124, c.967delT83) located on chromosome 12q22. Decorin proteins consisting of dermatan sulfate proteoglycans play a role in lamellar adhesion of collagens and control regular fibril-fibril spacing observed in the cornea, which contribute to corneal transparency. Therefore, this deletion of the decorin gene results in an abnormal protein formation of collagen fibrils. Corneal opacities can occur from disturbances in fibrillogenesis because corneal transparency depends on a regular arrangement of fibers.

In this study, we reported different aspects of CHSD structure and genetics in a patient diagnosed with CHSD who underwent penetrating keratoplasty, and we also conducted genetic evaluations for himself and his family members.

A 43-year-old man presented with a progressive deterioration of visual function for the previous seven years. The patient had no other ocular symptoms such as nystagmus or photophobia. His past history showed stable vision of 20 / 40 since trauma to his right eye when he was approximately 14 years of age. No other systemic abnormalities or malformations were recorded. His best-corrected vision was 20 / 400 in the right eye and 20 / 20 in the left, and his intraocular pressures were 25 mmHg in the right eye and 23 mmHg in the left eye at the time of his initial visit. Under slit lamp examination, a diffuse haze composed of a flaky pattern of stroma was noted throughout the entire cornea. The right eye had decreased vision and exhibited relatively denser homogenous opacities than the left (Fig. 1).

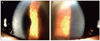

The family members stated that corneal changes had been detected only in the patient's mother at 69 years of age, and no specific issues had arisen in any other family member or relative. The patient's father had reported no ophthalmic abnormalities before his death, and his mother had been diagnosed with diffuse corneal opacities of unknown etiology in both eyes three years previously (Fig. 2). She explained that she had experienced decreased vision since childhood, but these deficiencies produced no difficulties in her daily life. The patient's brother and sister had no symptoms at all and no ophthalmic or systemic abnormalities. As far as the family knew, no one in the paternal or maternal lineage or offspring of the patient had experienced any eye problems except for the patient's mother (Fig. 3).

The endothelium and Descemet's membrane of the right eye were identified as normal following slit lamp examination. No gross abnormalities, such as Haab's striae or features of posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy, were detected in the right eye. The patient's past medical records from another hospital demonstrated that his endothelial cells of both eyes presented with a normal shape and numbers under a specular microscope about six years ago. However, endothelial cells were found as indeterminate forms using specular microscopy due to the barrier of stromal opacity at the time of our study. The endothelial cells of the left eye were counted using a Konan Noncon Robo-8400 noncontact specular microscope (Konan Medical Inc., Hyogo, Japan) as 2564 cells/m2. We assumed that the right eye would have a similar amount of endothelial cells and a relatively uniform morphologic pattern as those of the left.

Ultrasound corneal pachymetry (Humphrey Instruments Inc., San Leandro, CA, USA) revealed a central corneal thickness of 658 µm in the right eye and 632 µm in the left. The patient was suspicious for CHSD based upon clinical evidence, and he was scheduled for penetrating keratoplasty of the right eye. A corneal button was sent for light and electron microscopic analysis. There was no problem with corneal wound healing after keratoplasty, and the grafted cornea restored its transparency within two weeks. After 12 months, the corneal graft remained clear, and the patient's best-corrected visual acuity was 20 / 50 in the right eye.

Light microscopy with hemotoxylin and eosin staining revealed a normal epithelium and uninterrupted Bowman's membrane. The stromal lamellae were separated slightly from one another, forming a relatively compact space in between the anterior and the posterior stroma (Fig. 4). No Descemet's membrane or endothelium was detected in the original corneal button, apparently as the result of inappropriate specimen handling. Any infiltration, vessels, inflammatory, or storage material could not be detected.

Blood was sampled from the patient and family members for DNA collection and analysis [3]. DNA sequencing analysis of the decorin gene in chromosome 12q22 was positive in both the patient and his mother. The novel mutation of a heterozygous, nucleoside substitution (c.1036T>G) point mutation in the decorin gene was detected in both patients (Fig. 6). Lumican and keratocan sequence variants, which are closely located within the decorin gene, did not reveal any mutations. The c.1036T>G mutation resulted in a change of amino acid sequence (p.Cys346Gly). However, no genetic mutations were detected in other family members.

CHSD is an autosomal dominant inherited disease characterized by flaky or feathery stromal clouding. Its disease penetration is variable, and the condition is usually treated with keratoplasty in early childhood. It can be differentiated from congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy by the relatively normal corneal thickness and absence of corneal edema. Since the first report by Witschel et al. in 1978 [4], CHSD has been considered a rare corneal dystrophy; only four families have been reported: two French, one Belgian and one Norwegian [1,2,4,5]. To the best of our knowledge, our report includes the fifth family of CHSD worldwide and the first to be documented in Asia. The pathogenesis of CHSD is not yet well known. However, previous studies have reported characteristic histologic electron microscopic findings, which are characterized by multiple abnormal zones with an abnormal lucent ground substance separating the normal corneal stromal lamellae [1]. This pathologic characteristic of CHSD is principally attributable to abnormal fibrillogenesis in the cornea, which ultimately results in apparent stromal opacities and loss of corneal transparency.

Experimental evidence indicates that decorin proteins (which consist of dermatan sulfate proteoglycans) contribute to both the lamellar adhesive properties of collagen and the control of regular fibril-fibril spacing observed in the cornea [6-8]. Because corneal transparency requires the regular spacing of collagen fibrils of a uniform diameter and regular interfibrillar space, reduction in vision and associated symptoms can occur as the result of this abnormal fibrillogenesis caused by the truncated decorin protein. The decorin gene mutation was initially reported as a single base pair deletion (c.967delT) detected in a Norwegian family by Bredrup et al. in 2005 [1]. In 2006, Rodahl et al. [2] described another deletion mutation of the decorin gene (c.941delC) in a Belgian family.

In this case report, we detected a novel nucleotide substitution (c.1036T>G) in two members of an affected CHSD patient pedigree. This novel decorin gene mutation is different from previous mutations in that it is a nucleotide substitution rather than deletion. Interestingly, our electron microscopic findings were somewhat different from those of previous CHSD cases. The criss-crossing pattern of corneal collagen fibers was relatively intact. Moreover, the degree of visual impairment from corneal opacity seemed to be relatively minimal, since the patient maintained good vision until his late thirties. Usually, patients with CHSD lose their vision in early childhood. Considering the above distinctive features, we concluded our case as a relatively mild form of CHSD, since the nucleotide substitution may result in less structural or functional changes of the decorin protein than a nucleotide deletion. The authors also assert that the location of the mutation on the decorin gene can modulate the penetration of disease symptoms as well as the onset, duration, severity, and other associated ocular signs. Further investigations of the decorin gene and its diagnostic values are clearly warranted.

In summary, the patient in this report evidenced a late manifestation and mild symptoms with normal vision in the unaffected eye. The slight histopathologic changes in the cornea, mild deterioration of vision and novel decorin gene point mutation are dispositive for a mild form of CHSD. However, the unique process of disease and the aforementioned inconsistent tissue arrangements also raise salient questions as to the appropriateness of the diagnosis of CHSD. We categorized this case as an inherited disorder associated with a decorin gene mutation, as was reported by Bredrup et al. in 2005 [1]. Furthermore, future study will be required to evaluate the correlations between this disease and previously published cases of CHSD.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Slit lamp photography of the patient. (A,B) Right eye. No gross abnormalities of the corneal endothelium, iris and lens were observed. Clouding of the cornea is noticeable under the arcuate slit beam. With magnification, ground-glass corneal opacities are more clearly seen in the anterior stroma, and identifiable small flakes and spots are present throughout the entire stoma. (C,D) Left eye. Density of corneal clouding is less than that of the right cornea. |

| Fig. 2Slit lamp photography of the patient's mother. (A) Right eye. Corneal stroma with arcuate slit beam shows diffuse clouding in the right eye. (B) Left eye. Ground-glass corneal opacities and small flakes are similar to that of the right eye. |

| Fig. 4Patient's light microscope findings. (A) Irregularity of corneal collagen fibril formation. Relatively loose arrangement of collagen fibers in the anterior stroma (B) and a relatively dense arrangement in the posterior stroma (C) are observed. |

| Fig. 5Patient's transmission electron microscope findings. (A,B) A criss-crossing pattern of corneal fibers are shown with a relatively electron-dense (D) and lucent (L) structure. Irregularity in the collagen fibrils' shape and thickness is also seen. A keratocyte (K) is apparent in the electron lucent area (L). |

References

1. Bredrup C, Knappskog PM, Majewski J, et al. Congenital stromal dystrophy of the cornea caused by a mutation in the decorin gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005. 46:420–426.

2. Rodahl E, Van Ginderdeuren R, Knappskog PM, et al. A second decorin frame shift mutation in a family with congenital stromal corneal dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006. 142:520–521.

3. O'Connell JR, Weeks DE. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998. 63:259–266.

4. Witschel H, Fine BS, Grutzner P, McTigue JW. Congenital hereditary stromal dystrophy of the cornea. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978. 96:1043–1051.

5. Van Ginderdeuren R, De Vos R, Casteels I, Foets B. Report of a new family with dominant congenital heredity stromal dystrophy of the cornea. Cornea. 2002. 21:118–120.

6. Bonfield JK, Rada C, Staden R. Automated detection of point mutations using fluorescent sequence trace subtraction. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998. 26:3404–3409.

7. Michelacci YM. Collagens and proteoglycans of the corneal extracellular matrix. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003. 36:1037–1046.

8. Danielson KG, Baribault H, Holmes DF, et al. Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J Cell Biol. 1997. 136:729–743.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download