This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

We report two cases of choroidal neurofibromatosis, detected with the aid of indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) in patients with neurofibromatosis (NF)-1, otherwise having obscure findings based on ophthalmoscopy and fluoresceine angiography (FA). In case 1, the ophthalmoscopic exam showed diffuse bright or yellowish patched areas with irregular and blunt borders at the posterior pole. The FA showed multiple hyperfluorescent areas at the posterior pole in the early phase, which then showed more hyperfluorescence without leakage or extent in the late phase. The ICGA showed diffuse hypofluorescent areas in both the early and late phases, and the deep choroidal vessels were also visible. In case 2, the fundus showed no abnormal findings, and the FA showed weakly hypofluorescent areas with indefinite borders in both eyes. With the ICGA, these areas were more hypofluorescent and had clear borders. Choroidal involvement in NF-1 seems to occur more than expected. In selected cases, ICGA is a useful tool to be utilized when an ocular examination is conducted in a patient that has no definite findings based on the ophthalmoscope, B-scan, or FA tests.

Go to :

Keywords: Choroid, Choroidal neurofibroma, Indocyanine green angiography, Neurofibromatoses

Neurofibromatosis (NF) consists of at least two genetically distinct disorders: NF-1 (von Recklinghausen's or peripheral neurofibromatosis) and NF-2, which is formerly known as central neurofibromatosis [

1-

3]. NF-1, first observed by von Recklinghausen, manifests clinically in infancy with multiple cafe-au-lait skin spots, intertriginous freckling, iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules) and multiple cutaneous neurofibromas and is caused by genetic abnormalities on chromosome 17. NF-2 is characterized by bilateral vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas) and brain and spinal cord tumors, and it is transmitted by genetic abnormalities on chromosome 22. The prevalence of NF-1 is approximately 1 in 2,500 to 3,300 individuals, while NF-2 is observed in approximately 1 in 50,000 to 120,000 individuals, regardless of race, sex, or ethnicity [

2,

4].

NF can involve multiple organs, and the ocular manifestations of NF-1 include multiple iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules), congenital glaucoma, optic nerve gliomas, plexiform neurofibromas of the eyelids, and uveal hamartomas. On the other hand, retinal or choroidal lesions are rarely involved in the patients with NF-1 [

5-

8]. Furthermore, NF-1 patients tend to not undergo detailed ophthalmic examinations since NF-1 is rarely a vision-threatening disorder. In this study, we report two cases of choroidal abnormalities occurring in NF patients which were detected by fluoresceine angiography (FA) and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) in patients with NF-1 that had obscure fundus findings but good vision.

Case Reports

Case 1

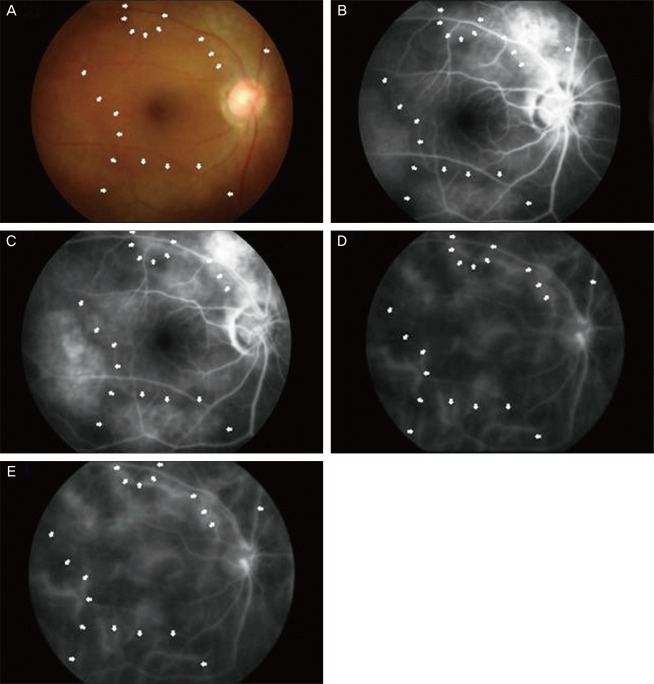

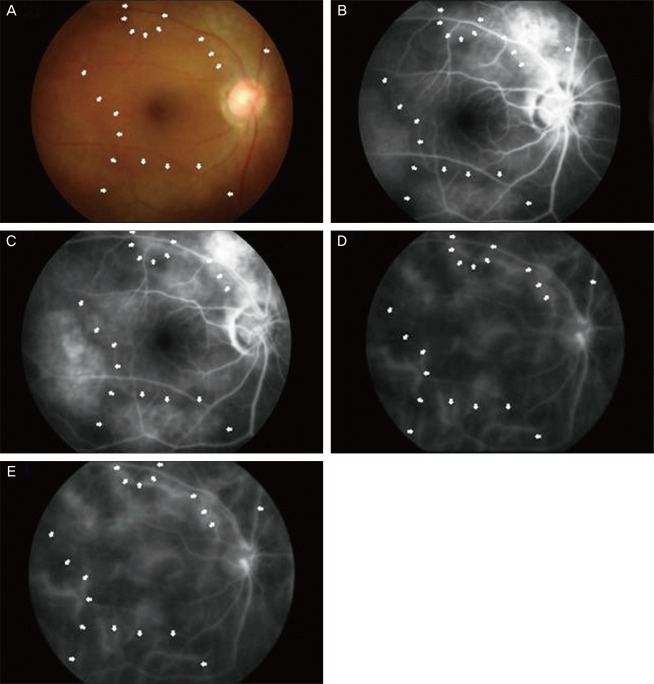

The following is a case of a 59-year-old female who had previously been diagnosed with NF type 1. She was referred to the Retina Clinic at Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital with the complaint of blurred vision for several months. Diagnosis was confirmed at the age of 55 years, and both her mother and sister had the same disease. Upon ocular examination, she had multiple iris hamartomas (Lisch nodule), and intraocular lenses with posterior capsular opacity in both eyes. The patient had cataract surgeries in both eyes 2 years prior to our examination. Her visual acuity was 20 / 120 in the right eye and 20 / 60 in the left eye at the time of her initial visit. After laser capsulotomy, the vision in both of her eyes improved to 20 / 20. At the follow-up visit, the fundoscopic exam showed diffuse bright or yellowish patched areas with irregular and blunt borders at the posterior pole. Although alterations were not clearly visible by fundoscopy, there was a slightly patched pattern or an uneven surface on the posterior pole (

Fig. 1A). The FA showed multiple hyperfluorescent areas at the posterior pole in the early phase, and then these areas showed more hyperfluorescence without leakage and were extent in the late phase (

Fig. 1B and 1C). These areas corresponded to the multiple yellowish patched lesions that were invisible in fundoscopy. The ICGA showed diffuse hypofluorescent areas in both the early and late phase, and the deep choroidal vessels were visible (

Fig. 1D and 1E)

| Fig. 1Case 1. Diffuse bright or yellowish patched areas with irregular and blunt borders at the posterior pole (A). Early-phase fluorescein angiography of the same eye shows several hyperfluorescent areas at the posterior pole, and these areas correspond to the bright patched areas that are seen in fundoscopy. These represent the zones of retinal pigmented epithelium alterations. These areas appear more hyperfluorescent with the same extent in the late phase (B,C). Indocyanine green angiography showed diffuse hypofluorescent areas in both the early and late phases, and the deep choroidal vessels are visible within the hypofluorescent area (D,E).

|

Case 2

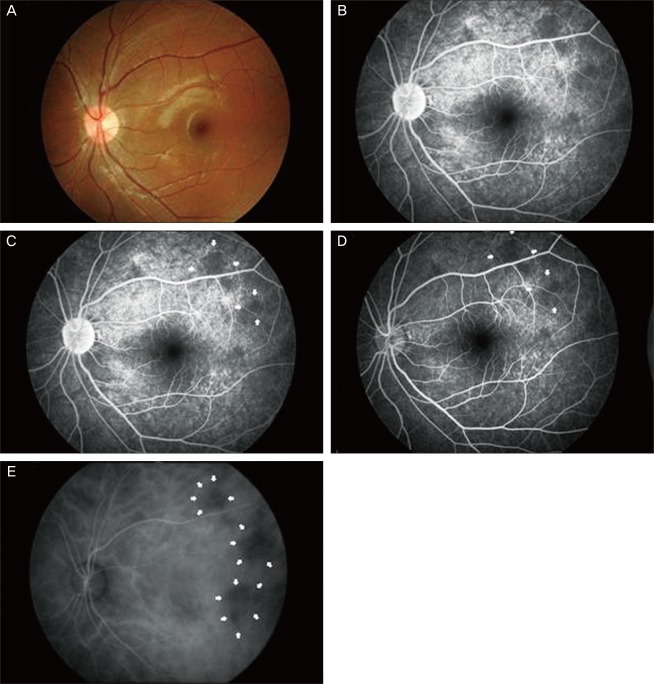

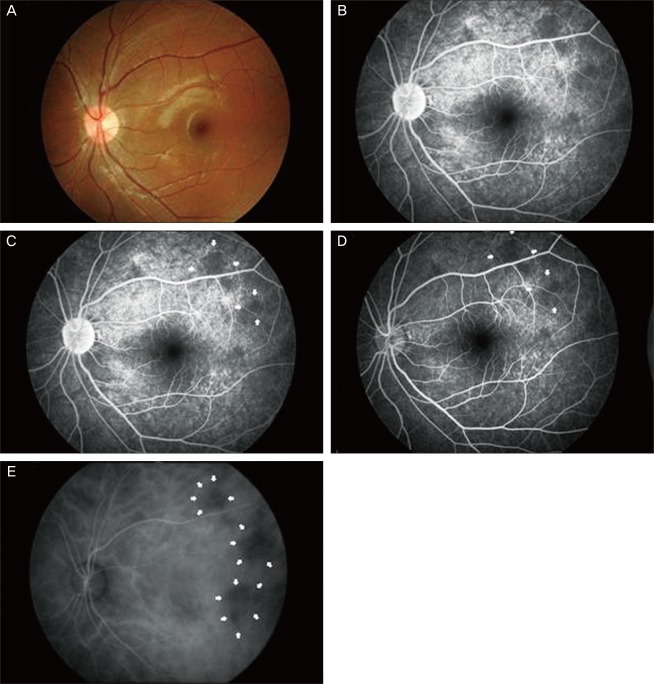

An 11-year-old male patient with NF-1 was referred to the Retina Clinic at Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital for an ophthalmological examination. The patient had no relatives with the same disease and had multiple cutaneous neurofibromas over the body, although these were only systemic manifestations. Visual acuity was 1.0 in both eyes, and the microscopic examination showed Lisch nodules in both eyes. The fundus and FA showed no definite abnormalities in either eye (

Fig. 2A-2D). However, the ICGA showed multiple hypofluorescent areas with clear borders in the early phase, which remained small or disappeared completely in the late phase (

Fig. 2E).

| Fig. 2Case 1. Diffuse bright or yellowish patched areas with irregular and blunt borders at the posterior pole (A). Early-phase fluorescein angiography of the same eye shows several hyperfluorescent areas at the posterior pole, and these areas correspond to the bright patched areas that are seen in fundoscopy. These represent the zones of retinal pigmented epithelium alterations. These areas appear more hyperfluorescent with the same extent in the late phase (B,C). Indocyanine green angiography showed diffuse hypofluorescent areas in both the early and late phases, and the deep choroidal vessels are visible within the hypofluorescent area (D,E).

|

Go to :

Discussion

Many studies have reported ocular manifestations in NF-1 patients, including choroidal abnormalities [

9-

16]. However, most of these cases are included in histopathologic studies or have abnormalities that are definitely observable with the fundoscope. Choroidal neurofibromatosis is thought to be a rare form of neurofibromatosis that affects the eyes [

9,

10,

14-

16]. The actual prevalence of this disorder may be higher than currently believed because patients with good vision tend not to undergo ocular examinations. Thus, without an ocular examination, which usually involves a conventional ophthalmoscopic examination or FA, patients with good vision are not tested for choroidal abnormalities. In some patients, the choroid neurofibromatosis may appear as yellowish nodules, but these may appear as bright patched areas upon fundoscopic examination in only weakly affected patients. FA shows irregular hyperfluorescence that is related to retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) alteration, but it is not able to detect underlying choroidal abnormalities.

ICGA has overcome the limitations of FA in regard to imaging of the choroidal structure [

17-

20]. Several authors have previously reported the presence of choroidal neurofibromatosis with the use of ICGA. Yasunari et al. [

21] have reported that they were able to detect choroidal abnormalities in all 17 of their patients with NF-1 using scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) and ICGA, and that the choroid was one of the structures most commonly affected by NF-1. They suggested that the hypofluorescent areas on the ICGA, that appeared to be obscure with SLO and FA in their less affected patients, were probably not caused by disturbance of the choriocapillaris circulation, but rather by the presence of refractile tissue or material in the choroid. They believed that such refractile material presumably blocks the fluorescence from the underlying choroidal vessels and produces a hypofluorescent appearance which disappears on the ICGA at the late phase due to the indocyanine-green dye being extravasated into the choroidal stroma. In contrast, Rescaldani et al. [

10] have suggested in their study that the early hypofluorescent areas in the ICGA are due to the hypo- or non-perfused lobules of the choriocapillaris rather than the blocking of fluorescent light by the neurofibromatose choroidal nodules since these areas became smaller or disappeared in the late phase and because the deep choroidal vessels were visible within these areas. Additionally, one histological study has documented that Schwann cell growth with dysplasia of the smooth muscle cells of the arteriolar wall leads to the gradual narrowing of the vessel lumen [

22]. According to Rescaldani et al. [

10], chronic hypoperfusion of the choriocapillaris appears to cause lesions to the overlying RPE and cause its eventual atrophy (yellowish patches on ophthalmoscopy that correspond to the hyperfluorescent areas in the FA).

In our case 1, the fundus did not show yellowish nodules but rather bright patched areas around the posterior pole, similar to Yasunari's cases. These lesions appeared to be hyperfluorescent areas in the FA, which suggests RPE alterations are present. However, the ICGA showed diffuse hypofluorescence with visible deep choroidal vessels from the early phase to the late phase and was unrelated to the lesion observed by both fundoscopy and FA. This finding is believed to be due to the diffuse scattering of the neurofibromatose tissue in the choroid without remarkable prominence. In regard to case 2, the abnormal alterations were not clearly visible by either fundoscopy or FA. However, the ICGA showed multiple hypofluorescent areas that persisted into the late phase. It is thought that multiple neurofibromas occupying the choroid were detected by the ICGA, and that these neurofibromas were not yet producing RPE abnormalities. However, it is insufficient to conclude that these abnormalities presented with choroidal neurofibromas because various possibilities exist for the underlying cause. Choroidal involvement in NF-1 may occur more often than what is currently believed. Also, the underlying cause of this, whether it be due to the space-occupying neurofibroma itself or the vascular change associated with the neurofibromatosis, may lead to the hypoperfusion of the lesion that would later result in RPE alteration. We believe that these ICGA patterns that are seen in our cases may not be due to hypoperfusion or nonperfusion of the choroidal lobules, but due instead to blocked fluorescence by the choroid-occupying materials.

In conclusion, these two cases have shown that choroidal abnormalities occur more often than currently believed in patients with NF-1. Fundoscopic examination can identify grossly proliferative neurofibromatosis but only in the later stages, and FA can only describe actual RPE alterations, secondary to choriocapillaris nonperfusion. However, ICGA is a useful tool to detect the early changes that occur with choroid abnormalities. Although no abnormal finding was found by either fundoscopy or FA, ICGA seems to be useful for ocular examinations of NF-1 patients that have good vision.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download