Abstract

Figures and Tables

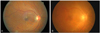

| Fig. 1Fundus photography of the right eye. (A) Before intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide (IVTA), only mild diabetic changes can be seen. (B) Five months after IVTA, anterior chamber inflammation, severe arterial obstruction, and vitreous opacity developed. |

| Fig. 2Montage fundus photography. (A) Five months after intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection, anterior chamber inflammation, severe arterial obstruction, and vitreous opacity developed. A white necrotic retinal area (black arrows) and vitreous opacity developed. Intravitreal triamcinolone is still visible in the inferior vitreous (white arrow). (B) After anti-viral treatment, the necrotic retinal area and vitreous opacity were gradually resolved. One month after antiviral medication, the white retinal necrotic area eventually disappeared. |

Table 1

IVTA = intravitreal triamcinolone injection; AC = anterior chamber; IOP = intraocular pressure; VA = visual acuity; CSME = clinically significant macular edema; DR = diabetic retinopathy; NIDDM = non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus; CMV = cytomegalovirus; PDT = photodynamic therapy; ARN = acute retinal necrosis; HSV = herpes simplex virus; N/A = not available; AMD = age-related macular degeneration; BRVO = branch retinal vein occlusion; CME = cystoid macular edema; CRVO = central retinal vein occlusion; ERM = epiretinal membrane; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; IRF = intraretinal fluid; IRU = immune recovery uveitis; IV = intravenous; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; VZV = varicella zoster virus.

*Visual acuity was limited to 6 / 36 due to cataract formation.

†Oral or IV antiviral treatment were administered. Exact route of drug administration was not mentioned.

‡Vitrectomy was performed before viral retinitis was developed.

§Anterior chamber inflammation was mentioned but the grade of inflammation was not available.

∥After cataract surgery, visual acuity was improved to 20 / 63.

#After cataract surgery and vitrectomy for epiretinal membrane removal, visual acuity was improved to 20 / 40.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download