Abstract

A 69-year old man presented to us with decreased vision in his right eye and a relative afferent pupillary defect. Under the presumption that he was suffering from retrobulbar optic neuritis or ischemic optic neuropathy, visual field tests were performed, revealing the presence of a junctional scotoma. Imaging studies revealed tumorous lesions extending from the sphenoid sinus at the right superior orbital fissure, with erosion of the right medial orbital wall and optic canal. Right optic nerve decompression was performed via an endoscopic sphenoidectomy, and histopathologic examination confirmed the presence of aspergillosis. The patient did not receive any postoperative antifungal treatment; however, his vision improved to 20 / 40, and his visual field developed a left congruous superior quadrantanopsia 18 months postoperatively. A junctional scotoma can be caused by aspergillosis, demonstrating the importance of examining the asymptomatic eye when a patient is experiencing a loss of vision in one eye. Furthermore, damage to the distal optic nerve adjacent to the proximal optic chiasm can induce unusual congruous superior quadrantanopsia.

Aspergillus is a ubiquitous, typically saprophytic fungus. Infection of the paranasal sinuses by aspergillus is not uncommon and is known to occur in immunocompromised patients, such as those with diabetes, malignancy, the elderly, and those taking corticosteroids. Non-invasive aspergillosis remains localized in the sinuses, whereas invasive aspergillosis is associated with ulceration and destruction of the sinus, as well as hematogenous spread [1,2]. When the infection spreads beyond the sphenoid sinus, it can lead to orbital apex syndrome, compressive optic neuropathy, or optic neuritis due to its geographic proximity to the optic nerve [3-5]. Here, we report a case of indolent invasive aspergillosis presenting as a junctional scotoma.

A 69-year old man presented to us with a one month history of decreased vision in his right eye. He was in good physical condition with no history of diabetes. His right vision was hand motion with a relative afferent pupillary defect. His left vision was 20 / 20, including normal color vision. Latency of P100 for pattern visual evoked responses was delayed (146.6 ms) in the right eye. His erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 25, and his c-reactive protein was 0.5. Under the presumption of retrobulbar optic neuritis or ischemic optic neuropathy, fluorescein angiography and an automated Humphrey visual field test (HVF, Humphery Filed Analyzer; Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc., Dublin, CA, USA) were performed. Unexpectedly, the HVF revealed a superior temporal visual field defect in the asymptomatic left eye and a central scotoma in the symptomatic right eye, which was also a junctional scotoma (Fig. 1A). Therefore, magnetic resonance imaging was performed to examine the parasellar area. Axial T1 weighted images revealed an isointense mass-like lesion compressing the right optic canal adjacent to the chiasmatic groove. Coronal T2 weighted images revealed marked heterogeneous enhancement of the right sphenoid sinus and a mass like lesion near the optic nerve (Fig. 2A and 2B). There were no abnormalities in the brain parenchyma. A paranasal sinus computed tomography scan showed destruction of the right medial orbital wall and the distal inferonasal optic canal caused by a soft tissue lesion extending from the sphenoid sinus (Fig. 2C and 2D).

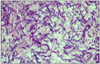

Right optic nerve decompression was performed through a massive endoscopic sphenoidectomy and histopathology confirmed aspergillus with dichotomous branching septate hyphae (Fig. 3). Postoperatively, the patient received no antifungal treatment due to private reasons; however, his vision was 20 / 40, and the HVF showed considerable improvement eight months postoperatively (Fig. 1B). At 18 months postoperative, the visual field developed into a left congruous superior quadrantanopsia without a temporal lobe or calcarine cortex lesion (Fig. 1C).

This case showed a junctional scotoma induced by aspergillosis. If the patient had been treated with high dose steroids aimed at controlling the optic neuritis, the infection could have progressed to fulminant invasive aspergillosis with extension into the orbit and brain, an affliction with an 80% mortality rate [3,6,7]. Therefore, this case illustrates the importance of examining the entire visual system in patients with visual loss in only one eye.

Aspergillosis of the paranasal sinus is classified as either invasive, non-invasive or as allergic aspergillus sinusitis [1,2]. The invasive type is characterized by the destruction of the bone due to intracranial or orbital extensions and is often difficult to differentiate from malignancy. It requires surgical resection and systemic antifungal treatment [8]. Non-invasive aspergilloma of the sinuses is a fungal ball with mucosal thickening and a variable degree of bony sclerosis. Non-invasive aspergilloma responds well to drainage and ventilation of the sinuses. It was not clear if this case involved the indolent invasive type or the severe non-invasive type. However, we successfully treated the aspergillosis, which had associated signs of invasion (bony erosion), without antifungal agents. Therefore, we assert that a meticulous and extensive initial surgical treatment is very important for the management of all types of aspergillosis, independent of antifungal drugs.

Our case showed unusual visual field changes. A junctional scotoma was found at the time of diagnosis, but the visual field defect developed into a congruous superior quadranatanopsia 18 months postoperatively, although no brain parenchyma lesion was present. This can be explained as follows; the entire right optic nerve adjacent to the proximal optic chiasm and the crossed inferonasal fibers of the left optic nerve were compressed by the asperogillosis. The right optic nerve rotates 45 degrees internally at the level of the junction of the optic chiasm [9]. Therefore, at that level, the right inferotemporal fibers are located in the lateral portion of the optic nerve, and the right inferonasal fibers are in the inferior portion of the optic nerve as they cross into the contralateral optic chiasm at Willbrand's knee. During the crossing, inferonasal fibers of the left optic nerve were compressed by the asperogillosis, while the right inferotemporal optic nerve fibers were simultaneously displaced laterally against the internal optic canal. Following surgery, most of the right optic nerve function improved, with the exception of severely damaged inferonasal fibers of the left eye and the inferotemporal fibers of the right eye that had been compressed against the lateral internal optic canal. Therefore, a left congruous superior quadrantanopsia developed. Undoubtedly, this kind of obvious congruous hemianopsia is a very rare condition in optic nerve damage. Furthermore, the visual defect becomes more congruent the further posterior the lesion is located, and 50% of all optic tract lesions may be congruent [10]. Therefore, the possibility of surgical trauma to an optic tract must be considered. However, according to its anatomic correlation with the sphenoid sinus, optic chiasm, and optic tract, the optic chiasm or optic tract are rarely damaged during sphenoidectomy.

Recently, the existence of Willbrand's knee has come into question [11]; however, the clinical localizing value of a junctional visual field loss remains. In our case, a junctional scotoma provided substantial evidence to help diagnose and explain the patient's vision loss.

The aim of this report was to illustrate that a junctional scotoma can be caused by aspergillosis and to emphasize the importance of ophthalmic examination of both eyes in any patient with presumed unilateral visual loss. Furthermore, damage to the distal optic nerve adjacent to the proximal optic chiasm can induce an unusual congruous superior quadrantanopsia.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Changes in visual field testing (Humphrey 30-2 program). (A) In the initial examination, the visual fields of both eyes demonstrated a junctional scotoma characterized by an ipsilateral central scotoma and a contralateral superotemporal field defect. (B) At 8 months postoperatively, visual filed testing revealed a slight improvement in the right visual field but no change in the left visual filed. (C) At 18 months postoperatively, visual field testing showed a definitive left congruous superior quadrantanopsia. |

| Fig. 2Magnetic resonance imaging. (A) Axial T1-weighted image showing an isointense mass-like lesion (arrow) compressing the right optic canal adjacent to the chiasmatic groove. (B) Coronal T2-weighted image showing marked heterogeneous enhancement of the right sphenoid sinus and a mass-like lesion near the optic nerve. (C) Axial paranasal sinus computed tomography (CT) scan showing erosion of the right medial orbital wall (arrow) extending from the sphenoid sinus with a thickened mucosa. (D) Coronal CT scan showing the thickened mucosa in the right sphenoidal sinus, an inflammatory soft tissue lesion around the optic nerve, and destruction of the inferonasal optic canal (arrow). |

References

1. Brown P, Demaerel P, McNaught A, et al. Neuro-ophthalmological presentation of non-invasive Aspergillus sinus disease in the non-immunocompromised host. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994. 57:234–237.

2. Hora JF. Primary aspergillosis of the paranasal sinuses and associated areas. Laryngoscope. 1965. 75:768–773.

3. Hedges TR, Leung LS. Parasellar and orbital apex syndrome caused by aspergillosis. Neurology. 1976. 26:117–120.

4. Pieroth L, Winterkorn JM, Schubert H, et al. Concurrent sinoorbital aspergillosis and cerebral nocardiosis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004. 24:135–137.

5. Weinstein JM, Sattler FA, Towfighi J, et al. Optic neuropathy and paratrigeminal syndrome due to Aspergillus fumigatus. Arch Neurol. 1982. 39:582–585.

6. Nielsen EW, Weisman RA, Savino PJ, Schatz NJ. Aspergillosis of the sphenoid sinus presenting as orbital pseudotumor. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1983. 91:699–703.

7. O'Toole L, Acheson JA, Kidd D. Orbital apex lesion due to Aspergillosis presenting in immunocompetent patients without apparent sinus disease. J Neurol. 2008. 255:1798–1801.

8. Bahadur S, Kacker SK, D'souza B, Chopra P. Paranasal sinus aspergillosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1983. 97:863–867.

9. Miller NR, Newman NJ, Hoyt WF, Walsh FB, editors. Walsh and Hoyt's clinical neuro-ophthalmology. 1998. 5th ed. Baltimore: Lipponcott Williams & Wilkins;104–106.

10. Kedar S, Zhang X, Lynn MJ, et al. Congruency in homonymous hemianopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007. 143:772–780.

11. Horton JC. Wilbrand's knee of the primate optic chiasm is an artefact of monocular enucleation. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1997. 95:579–609.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download