Abstract

We report the outcome of conventional epipolis laser in situ keratomileusis (Epi-LASIK, flap-on) and lamellar epithelial debridement (LED; Epi-LASIK, flap-off) in myopic patients with dermatologic keloids. Three patients, who were all noted to be susceptible to keloid scarring, received conventional Epi-LASIK in their right eyes and LED in their left eyes. The patients were followed-up for 6 to 21 months after their surgeries, and the outcomes were then evaluated. In case 1, the preoperative spherical equivalent (SE) was -6.5 diopters (D) in the right eye (OD) and -6.25 D in the left eye (OS). At 21 months postoperatively, the uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) was 20 / 12.5 in both eyes. In case 2, the preoperative SE was -5.25 (OD) / -6.00 (OS). After six months, the postoperative UCVA was 20 / 12.5 in both eyes. In case 3, the preoperative SE was -4.5 (OD) / -2.0 (OS). The UCVA at the six-month follow-up was 20 / 12.5 in both eyes. No adverse events, including corneal haze, occurred in any of the patients. All three of our patients reported excellent visual outcomes following both conventional Epi-LASIK and LED, despite their histories of keloid formation. The present cases suggest that both Epi-LASIK and LED may be safe and effective techniques for myopic patients with dermatologic keloids.

A keloid is a hyperproliferative growth of dense fibrous tissue that occurs beyond the borders of a wound due to an abnormal healing response to a cutaneous injury [1]. The results of photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) or laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) in patients with dermatologic keloids have been contradictory and could potentially be misleading [2-5]. Epipolis (Epi)-LASIK is an alternative surface ablation procedure for refractive surgery [6]. In conventional Epi-LASIK (flap-on), the epithelial sheet is repositioned on the stroma after ablation. Whereas, lamellar epithelial debridement (LED; Epi-LASIK, flap-off) is a modified surface ablation that results in complete removal of the epithelial flap [7].

To the best of our knowledge, neither the healing response nor the visual and refractive outcomes of conventional Epi-LASIK or LED in patients with keloids have been reported previously. In this report, we describe the outcomes of conventional Epi-LASIK and LED in myopic patients with dermatologic keloids that were confirmed via dermatological consultations.

Each of the three patients in this study simultaneously received conventional Epi-LASIK in the right eye and LED in the left eye. An epithelial flap was created in both eyes using the Amadeus II (AMO Inc., Santa Ana, CA, USA). We used a blade oscillation speed of 11,000 rpm, a translation speed of 1.5 mm per second, and a vacuum pressure of 800 mmHg, which resulted in 9.0 mm epithelial flaps. The laser treatment was performed using an excimer laser (VISX Star S4; VISX Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). After ablation, the epithelial flap was repositioned on the stroma in the right eye and was removed from the left eye. A soft contact lens (Focus, Ciba Vision, Duluth, GA, USA; B.C 8.8 mm, ф 12.0 mm) was placed onto the eyes at the end of the procedure. In this series of surgeries on a total of six eyes of three patients, the surgeries were performed uneventfully without any epithelial problems.

Moxifloxacin 0.5% (Vigamox; Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) and prednisolone acetate 1% (Pred Forte; Allergan, Westport, Ireland) eye drops were used every six hours for the first week after surgery. After the first week, 0.1% fluorometholone (Ocumetholone; Samil, Seoul, Korea) was administered four times daily for the first month, twice daily for the following month, and once a day for the third month. Routine postoperative examinations were scheduled at 1 day, 3 days, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months and 6 months from the surgery date.

A 25-year-old woman was evaluated for refractive surgery. She was noted to be susceptible to keloid scarring, as demonstrated by the presence of scars on both ears. Preoperative best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20 / 16 in both eyes. Preoperative spherical equivalent (SE) was -6.5 diopters (D) in the right eye (OD) and -6.25 D in the left eye (OS). Ophthalmic examination was unremarkable except for moderate myopia. Preoperative characteristics and demographics are shown in Table 1.

The uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) was 20 / 32 (OD) and 20 / 20 (OS) one day postoperatively. At 3 days, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months postoperatively, the UCVA was 20 / 100, 20 / 20, 20 / 20, 20 / 12.5 and 20 / 12.5 (OD) and 20 / 20, 20 / 20, 20 / 16, 20 / 12.5, and 20 / 12.5 (OS), respectively. The patient was invited to a re-examination 21 months after the surgery, when the SE was -0.125 D (OD) and -0.25 D (OS). No adverse events, including corneal haze, were observed in this patient, and her visual acuity remained at 20 / 12.5 in both eyes.

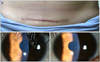

A 28-year-old woman was examined for refractive surgery. Her general history revealed a tendency to form keloids, as demonstrated by a scar on her left shoulder (Fig. 1A). Preoperative BCVA was 20/16 in both eyes, and preoperative SE was -5.25 D (OD) and -6.00 D (OS). Ophthalmic examination was normal except for moderate myopia. Preoperative characteristics and demographics are shown in Table 1.

One day postoperatively, the UCVA was 20 / 25 in both eyes. At 3 days, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months postoperatively, the UCVA was 20 / 20, 20 / 20, 20 / 16, 20 / 12.5, and 20 / 12.5 (OD) and 20 / 25, 20 / 20, 20 / 16, 20 / 12.5, and 20 / 12.5 (OS), respectively. At her final examination, the SE was -0.50 D (OD) and -0.25 D (OS). There were no postoperative complications such as corneal haze (Fig. 1B).

A woman 32 years of age was referred for refractive surgery. She had a tendency for keloids, which was indicated by the existence of an over-exuberant scar on her lower abdomen (Fig. 2A). Preoperative BCVA was 20/16 in both eyes. Preoperative SE was -4.50 D (OD) and -2.00 D (OS). Her ophthalmic examination was normal except for mild to moderate myopia. Preoperative characteristics and demographics are shown in Table 1.

One day postoperatively, the UCVA was 20 / 50 (OD) and 20/40 (OS). At 3 days, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months and 6 months postoperatively, the UCVA was 20 / 40, 20 / 25, 20 / 20, 20 / 12.5 and 20 / 12.5 (OD) and 20 / 32, 20 / 25, 20 / 20, 20 / 12.5 and 20 / 12.5 (OS), respectively. At the final follow-up, the SE was -0.25 D (OD) and -0.50 D (OS), and no postoperative adverse events occurred (Fig. 2B).

Both PRK and LASIK have been shown to be predictable and safe methods for the treatment of low to moderate refractive errors. There is, however, no consensus on the safety and efficacy guidelines of PRK or LASIK for patients with dermatologic keloids. Tanzer et al. [2] have reported that a history of keloid formation does not appear to adversely affect the outcomes of PRK. Similarly, Cobo-Soriano et al. [3] reported no difference in the anatomical or functional results following LASIK between patients with dermatologic keloids and those without. In addition, Artola et al. [4] concluded that LASIK is a predictably safe and effective technique for myopic patients with dermatologic keloids. However, Girgis et al. [5] reported significant corneal haze after LASIK and PRK in a Caucasian patient with a history of dermatologic keloids. The United States Food and Drug Administration also requires the labeling of excimer lasers that are approved for PRK and LASIK to include any history of keloid formation as a relative contraindication to laser refractive surgery.

Keloids are characterized by the uncontrolled synthesis and excessive deposition of collagen and glycoproteins. It has been suggested that keloid keratinocytes play an important role in keloidogenesis by influencing fibroblasts. Keratinocytes may promote proliferation and oppose the apoptosis of fibroblasts though paracrine effects such as increased expression of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β [8,9]. Similar to keloidogenesis, cytokines and growth factors such as TGF-β1 are released into the tear film by the lacrimal gland after corneal epithelial injury [10]. During the regeneration of the epithelium after refractive surgery, these cytokines and growth factors from the tear fluid may penetrate the corneal stroma, which may potentially activate stromal keratocytes. Theoretically, the activated keratocytes at the borders of the ablation zone may transform into myofibroblasts, which may in turn migrate into the subepithelial space and result in corneal haze [11].

Pallikaris et al. [6] have described an alternative for epithelial separation using an instrument called an epikeratome. The epithelial sheet is repositioned on the stroma after ablation in conventional Epi-LASIK and is removed from the stroma in LED [7]. Katsanevaki et al. [12] inspected epithelial flaps that were harvested 24 hours after they were accidentally dislocated during the Epi-LASIK procedure and found that most epithelial cells were morphologically normal with only minor cell degeneration. Since relatively minor corneal epithelial injury typically occurs in Epi-LASIK and LED, fewer cytokines and growth factors such as TGF-β1 may be released into the tear film. In support of this, Long et al. [13] reported that TGF-β1 levels are lower in the tear fluid measured after the Epi-LASIK procedure compared to that after the LASEK procedure. Therefore, the risk of corneal haze or keloid formation after refractive surgery may be lower in Epi-LASIK and LED than in PRK and LASIK. In the present study, the patients, who underwent conventional Epi-LASIK in the right eyes and LED in the left eyes, exhibited significant improvement in UCVA, BCVA, and SE refraction along with an absence of postoperative adverse events.

Recent studies of keloids suggest that the stretching tension of the body surface is also an important condition that is associated with keloid generation [8,14]. Al-Attar et al. [8] reported that the mechanical tension that is placed on the healing wound drives fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis. Akaishi et al. [14] proposed that adhesion with the subcutaneous bone structures greatly increased the tension applied to the keloid. The lack of significant stretching tension and underlying hard tissues in the cornea, therefore, might contribute to the favorable outcomes of no corneal haze in these cases.

In conclusion, all of our patients, who had a tendency to form dermatologic keloids, had excellent visual outcomes following conventional Epi-LASIK and LED, showing that it is possible to perform these procedures safely and effectively in patients with keloids. Further investigation with more keloid patients may expand upon the promising results seen in this study.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Photographs of a 28-year-old woman (case 2). (A) Keloid scar on the left shoulder. (B) No subepithelial corneal haze in either eye at six months postoperatively. OD = right eye; OS = left eye.

References

1. Robles DT, Berg D. Abnormal wound healing: keloids. Clin Dermatol. 2007. 25:26–32.

2. Tanzer DJ, Isfahani A, Schallhorn SC, et al. Photorefractive keratectomy in African Americans including those with known dermatologic keloid formation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998. 126:625–629.

3. Cobo-Soriano R, Beltran J, Baviera J. LASIK outcomes in patients with underlying systemic contraindications: a preliminary study. Ophthalmology. 2006. 113:1118.e1–1118.e8.

4. Artola A, Gala A, Belda JI, et al. LASIK in myopic patients with dermatological keloids. J Refract Surg. 2006. 22:505–508.

5. Girgis R, Morris DS, Kotagiri A, Ramaesh K. Bilateral corneal scarring after LASIK and PRK in a patient with propensity to keloid scar formation. Eye (Lond). 2007. 21:96–97.

6. Pallikaris IG, Katsanevaki VJ, Kalyvianaki MI, Naoumidi II. Advances in subepithelial excimer refractive surgery techniques: Epi-LASIK. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2003. 14:207–212.

7. Wang QM, Fu AC, Yu Y, et al. Clinical investigation of off-flap epi-LASIK for moderate to high myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008. 49:2390–2394.

8. Al-Attar A, Mess S, Thomassen JM, et al. Keloid pathogenesis and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006. 117:286–300.

9. Xia W, Phan TT, Lim IJ, et al. Complex epithelial-mesenchymal interactions modulate transforming growth factor-beta expression in keloid-derived cells. Wound Repair Regen. 2004. 12:546–556.

10. Baldwin HC, Marshall J. Growth factors in corneal wound healing following refractive surgery: a review. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002. 80:238–247.

11. Kaji Y, Soya K, Amano S, et al. Relation between corneal haze and transforming growth factor-beta1 after photorefractive keratectomy and laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001. 27:1840–1846.

12. Katsanevaki VJ, Naoumidi II, Kalyvianaki MI, Pallikaris G. Epi-LASIK: histological findings of separated epithelial sheets 24 hours after treatment. J Refract Surg. 2006. 22:151–154.

13. Long Q, Chu R, Zhou X, et al. Correlation between TGF-beta1 in tears and corneal haze following LASEK and epi-LASIK. J Refract Surg. 2006. 22:708–712.

14. Akaishi S, Akimoto M, Ogawa R, Hyakusoku H. The relationship between keloid growth pattern and stretching tension: visual analysis using the finite element method. Ann Plast Surg. 2008. 60:445–451.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download