Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to understand the mechanism of apoptosis occurring on a cultured human lens epithelial cell line after exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light. We intended to confirm the presence of cellular toxicity and apoptosis and to reveal the roles of p53, caspase 3 and NOXA in these processes.

Methods

Cells were irradiated with an ultraviolet lamp. Cellular toxicity was measured by a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay. Hoechst staining and fluorescent anti-caspase 3 antibodies were used for apoptosis investigation. The quantities of p53, caspase 3, and NOXA were measured by Western blotting for to investigate the apoptosis pathway.

Results

Cellular toxicity on the human lens epithelium markedly increased with time after UV exposure. On Hoechst staining, we found that apoptosis also remarkably increased after exposure to ultraviolet light, compared with a control group. In the immunochemical study using anti-caspase 3 antibodies, active caspase 3 significantly increased after exposure to ultraviolet light. On Western blotting, p53 decreased, while caspase 3 and NOXA increased.

Conclusions

Exposure of cultured human lens epithelial cell lines to ultraviolet light induces apoptosis, which promotes the expression of NOXA and caspase 3 increases without increasing p53. This may suggest that UV induced apoptosis is caused by a p53-independent pathway in human lens epithelial cells.

Previous research has shown that exposure to ultraviolet light is an environmental factor for the appearance of cataracts [1]. Recently, many studies have tried to find the biochemical mechanism connecting ultraviolet (UV) exposure to cataracts by experimentally investigating the opacity of the human crystal lens caused by ultraviolet light [2]. Despite these efforts, the exact mechanism of the interaction between ultraviolet light and the human lens is not clearly understood. The human lens is continuously exposed to small quantities of ultraviolet light every day, but, if this exposure exceeds a certain level, the lens may become irrevocably damaged [3].

Apoptosis, which is a cell's controlled death, is very important in maintaining homeostasis. Genetically normal genes make apoptosis [4]. It is important to understand the exact mechanism of controlling the apoptosis route in detail by removing the genetically defective cells in an object and the cells that are in abnormal cell cycles caused by cell cycle promoting actors.

There is currently active research studying the genes involved in apoptosis [5].It is known that increased p53 expression in the rat lens epithelium following exposure to UV light is associated with apoptosis and cataracts [6]. The intrinsic cell death machinery is dependent on the activation of a number of proteases called caspases and NOXA [7,8].

The purpose of this study is to understand the mechanism of apoptosis that occurs in cultured human lens epithelial cells after exposure to ultraviolet light. We intend to confirm the presence of cellular toxicity and apoptosis and to understand the roles of p53, caspase 3, and NOXA in these processes.

The human lens epithelial line CRL-1142 (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) was used for this study. These human lens epithelial cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), which is composed of 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 u/mL), and nystatin (25 ug/mL) at 37℃ in humidified atmosphere, containing 5% CO2.

The human lens epithelial cells were irradiated for 30 seconds with an irradiance of 0.6 mW/cm2 after removal of the serum-free growth medium. UV irradiance was modulated by adjusting the lamp output, calibrated with a UV sensor (FS-20 T12-UVB; National Biological Corp., Beachwood, OH, USA). The UVB spectrum was between 280 nm and 320 nm with peak irradiance at 312 nm. The total exposure volume of UVB was 18 mJ/cm2. After 0, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 hours incubation, cell viability was evaluated by a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Briefly, MTT is reduced to purple formazan in the mitochondria of living cells. A solubilization solution is added to dissolve the insoluble purple formazan product into a colored solution. The MTT assay was then carried out using a standard protocol and the optical density was measured at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer.

We compare the control group (not exposed to UV irradiation) with the experimental group (4 hours after 18 mJ/cm2 UV shot). We followed a previously described protocol for the experimental group. The cells were washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and resuspended to 1 × 106 cells/mL in PBS. An equal volume of Hoechst dye was then added (working solution 5 mM). Hoechst dye allows easy observation of the changes in nuclei by producing a bright fluorescence at 465 nm. We incubated the cells for 15 min at 37℃, and then either analyzed the cells for fluorescence or washed the cells and fixed them in paraformaldehyde (in 1% PBS) for future analysis.

We compare the control group (not exposed to UV irradiation) with the experimental group (4 hours after 18 mJ/cm2 UV shot). We followed a previously described protocol for the experimental group. The cells, which were cultured on the cover glass, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at normal temperature for 30 minutes and then washed with PBS (pH 7.4). In order to increase the permeability, 0.1% sodium citrate (pH 6.0), which contains 0.1% triton X-100, was added and allowed to react for 2 minutes. The primary antibody, caspase 3 (1:50), was allowed to react at room temperature for 120 minutes and the cells were then washed with PBS. The secondary antibody, Alex Flour goat anti-rabbit 488 (1:200), was allowed to react at room temperature for 60 minutes, washed with PBS, and visualized under a fluorescent microscope (Leica EL6000; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

For Western blot analysis, membranes were incubated overnight at 4℃ with the rabbit primary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA) diluted in 3% skim milk. The blots were then incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature (RT) with rabbit primary antibodies against phospho-Akt (Ser473) (1:1,000), Akt (1:1,000), phospho-FKHR (Ser256) (1:1,000),and phospho-GSK-3β (Ser9) (1:1,000). After washing three times (20 minutes per wash) using Tris-buffered saline Tween-20, the blots were incubated with anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:5,000 in 2% milk; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) for 60 minutes at RT. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence light detection kit (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Beta-actin (GeneTex Inc., San Antonio, TX, USA) was used as an internal control. In all of the figures with densitometry data, optical density refers to the integrated density.

To increase the reliability of the data, all experiments were repeated 3 times and the average values were obtained. SPSS ver. 10.1 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to compute routine statistics. The data was analyzed for significance using repeated measures, followed by Duncan's multiple range tests. The data are expressed as a mean percentage of the control value plus standard error measurement. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

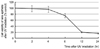

After the human lens epithelial cells were exposed to ultraviolet light, the survival rate was measured by MTT assay at 0, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 hours later. The cell viability decreased with time. The MTT reduction ratios for the control group and at6 hours and 12 hours after UV exposure were 100, 72 ± 4.9, and 21.5 ± 6.7% respectively (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1).

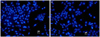

In order to investigate the appearance of apoptosis, Hoechst staining was performed. The control group showed normal nuclei appearance without nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 2A). The experimental group (4 hours after UV exposure) showed abnormal nuclei appearance with nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 2B). It appeared that the fragments moved to neighboring cells or that neighboring cells moved to embrace the fragments. In order to investigate the apoptotic phenotype, an immunochemical study using anti-caspase 3antibodies was performed. The control group showed no fluorescent signal corresponding to active caspase 3 protein (Fig. 3A), while the experimental group showed a high fluorescent signal (Fig. 3B). The signal became significantly stronger and more distributed throughout the cytoplasm and nuclei with a spotted character after UV exposure. In the nuclei, the fluorescence exhibited a clustered pattern.

In order to investigate apoptosis gene expression, Western blotting was performed. We once again compared the control group with the experimental group 4 hours after UV exposure. On the Western blot examination, an immune band was observed around 53kDa (Fig. 4A). The expression of p53, caspase 3 and NOXA relative to beta-actin (GeneTex Inc.), used as an internal control, was analyzed. We found that p53 decreased from 86 to 40, caspase 3 increased from 25 to 103 and NOXA increased from 24 to 194 (Fig. 4B).

Apoptosis was first defined by Kerr et al. in 1972. In the last step of apoptosis, a cell divides into several smaller cells that are called "apoptotic bodies" [9]. Genetically normal genes make apoptosis, and it is a controllable, positive cell death process. This process is accompanied by a reduction of a cell's specific gravity; destruction of cell membranes; condensation of chromosomes; and transformation of apoptotic bodies into cysts which then undergo phagocytosis [10]. In an experiment using a large mouse, researchers found that apoptosis caused by ultraviolet light reached its maximum within 24 hours of exposure [11]. While removal of cells may be beneficial to an organism, in certain conditions, apoptosis can kill cells that are essential for continued function. In the case of lenses, proteases such as caspases are involved in cell death, and these enzymes might be activated after the oxidative damage to the lens [12].

Cataracts usually start on the lens epithelium [13]. The lens epithelium grows as a cell layer under the front bag and has a generally low capability for proliferation, especially in the central layer. The cells there have a very low capability for proliferation, but they can proliferate very quickly under abnormal circumstances [14]. Several medical experiments on living bodies have shown that the lens epithelium, after exposure to ultraviolet light, promptly removes damaged cells (such as apoptotic cells) and proliferates normal cells which replace the damaged cells [15]. Therefore, it is important to study the role of the lens epithelium in protecting against ultraviolet light and to understand how the lens epithelium may recover after being damaged. Although UV irradiation causes various kinds of modifications in lens epithelial cells, the earliest consequences are probably damage to DNA and membrane pumps [4]. It is conceivable that UV-damaged membranes would allow an influx of calcium into lens epithelial cells, which is known to activate apoptosis [16]. The quick death of lens epithelial cells through apoptosis following UV irradiation would eliminate homeostatic epithelial cell control of the underlying fiber cells, leading to impairment of the integrity of these underlying fiber cells. Such reactions, plus direct damage at the DNA and membrane levels, may lead to the observed loss of epithelial cell viability [17]. The death of the epithelial cells plus the UV-induced damage to the fiber cell proteins may lead to rapid lens opacification.

In the human body, there are genes that suppress cancers (called "cancer or tumor suppressing genes") which are being investigated using genomic research techniques. One such gene is p53, which is found on chromosome 17 and which produces p53 protein to kill cancer cells. p53 is one of the most commonly studied genes in apoptosis research, as it prevents various types of cells from proliferating and may lead them to apoptosis. A targeted gene that receives a signal from p53 becomes unified with p53 to make various proteins that recover DNA and fight cancers [18]. Additionally, p53 also has a strong relationship with apoptosis in human lens epithelial cells [19], and there is some evidence that the p53 pathway may be involved in lens development. Expression of p53 has been demonstrated in the lens epithelial cells of the central and pre-equatorial zones and in the lens fibre nuclear bow region, while increased p53 expression in rat lens epithelial cells following exposure to UV light has been found to be associated with apoptosis and cataracts [20]. Furthermore, temporally distinct patterns of p53-dependent apoptosis have been identified during mouse lens development [21].

However, once the p53 gene is damaged, it gets to lose the ability of apoptosis and can no longer prevent the proliferation of cancer cells [22]. Cellular stresses, such as growth factor deprivation and DNA damage, lead to stabilization and activation of the p53 tumor suppressor protein [23]. Depending on the cellular context, this can result in one of two different outcomes: cell cycle arrest or apoptotic cell death. Cell death induced through the p53 pathway is executed by caspase proteinases, which, by cleaving their substrates, lead to the characteristic apoptotic phenotype [24]. Caspase activation by p53 occurs through the release of apoptogenic factors from the mitochondria, including cytochrome C. Released cytochrome C allows for the formation of a high-molecular weight complex, the apoptosome, which consists of the adapter protein Apaf-1 and caspase 9, which is activated following recruitment into the apoptosome. Active caspase 9 then cleaves and activates the effector caspases, such as caspases-3 and -7, which execute the death program [25]. The release of mitochondrial apoptogenic factors is regulated by the pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, which either induce or prevent the permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane. Some of the pro-apoptotic family members, such as BAX, NOXA or PUMA, are transcriptional targets of p53. The elucidation of the p53-dependent pathway, resulting in mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization through the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family of proteins, is key to understanding the mechanism of stress-induced apoptosis [26]. NOXA is a pro-apoptotic BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family of proteins that is up regulated at a transcriptional level by the nuclear protein p53 in response to cellular stresses such as DNA damage or growth factor deprivation. NOXA is able to interact with anti-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family and causes the release of cytochrome C into the cytosol, leading to the activation of caspases and induction of apoptosis [27].

A research group at the medical system in Tokyo University revealed that NOXA was a newly-targeted gene of p53and clarified that NOXA leads apoptosis. The expressed NOXA moves to the mitochondria of cells and promotes the discharge of cytochrome C, an inducer of apoptosis. If this NOXA gene is removed, apoptosis does not occur (even partially), even though p53 is forcibly expressed. Therefore, NOXA is an important factor in the execution of apoptosis through p53 [8]. However, it has recently been shown that there is an additional pathway for NOXA expression that works independently of p53 [28].

Jullig et al. [29] have discovered that MG132 induces NOXA expression via a p53-independent mechanism that leads to caspase-dependent apoptosis. A research team led by Armstrong JL of Northern Institute for Cancer Research, School of Clinical and Laboratory Sciences, Newcastle University, UK, has shown that NOXA is important in p53-independent fenretinide-induced apoptosis of neuroectodermal tumors [30]. These results demonstrate the importance of NOXA induction in determining the apoptotic response to fenretinide and emphasize the role of NOXA in p53-independent apoptosis. This study also suggests that there may be a NOXA protein that appears independently of p53 (in addition to NOXA that arises directly from increases in p53). We found that UV light caused apoptosis and an increase in cell toxicity on cultured human lens epithelial cells, and that this apoptosis promoted the expression of NOXA independently of p53. Our study was designed to understand the possible mechanisms of apoptosis on cultured human lens epithelial cells after exposure to ultraviolet light. We found that exposure to ultraviolet light increased cellular toxicity and induced apoptosis, although apoptosis only occurred after at least 6 hours post-exposure. It is possible that the concentrations of apoptosis initiators are low initially, and increase with time [31,32]. We also found increased expression of NOXA and caspase 3 without increased expression of p53. This may suggest that UV induced apoptosis in human lens epithelial cells follows a p53 independent pathway. Additional research is needed to better understand the workings of this p53 independent pathway.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

After human lens epithelial cells were exposed to ultraviolet light, the survival rate (mean±SD) was measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay at 0, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 post-exposure. The MTT reduction ratios among the control group, 6 hour post-exposure group, and 12 hour post-exposure group were 100, 72 ± 4.9, and 21.5 ± 6.7%, respectively (p < 0.05). Cell viability decreased with time. UV = ultraviolet.

Fig. 2

Hoechst staining. (A) The control group, which was not exposed to ultraviolet irradiation, showed normal nuclei appearance without nuclear fragmentation. (B) The experimental group (4 hours post-exposure) showed abnormal nuclei appearance with nuclear fragmentation. It appeared that the fragments moved to neighboring cells or that neighboring cells move to embrace the fragments.

Fig. 3

An immunochemical study using anti-caspase 3 antibodies (A). The control group showed no fluorescent signal corresponding to active caspase 3 protein. (B) The experimental group showed a significantly increased fluorescent signal corresponding to active caspase 3 protein. The fluorescent signal was significantly strong and distributed throughout cytoplasm and nuclei with a spotted character after ultraviolet exposure.

Fig. 4

Gene expressions were evaluated by Western blotting. We compared the control group with the experimental group (4 hours post-exposure). (A) An immune band was observed around 53kDa. The expression of p53, caspase 3 and NOXA relative to beta-actin (GeneTex Inc., used as an internal control) was checked. (B) p53 decreased from 86 to 40, caspase 3 increased from 25 to 103 and NOXA increased from 24 to 194. C = control; UV = ultraviolet.

References

1. Hightower KR. The role of the lens epithelium in development of UV cataract. Curr Eye Res. 1995. 14:71–78.

2. Sasaki K. Matthes R, editor. International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection. International Commission on Illumination. The lens-human data from chronic exposure: UV related cataract. Measurements of optical radiation hazards. 1998. Oberschleissheim: International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection;179–192.

3. Taylor HR, West SK, Rosenthal FS, et al. Effect of ultraviolet radiation on cataract formation. N Engl J Med. 1988. 319:1429–1433.

4. Kleiman NJ, Wang RR, Spector A. Ultraviolet light induced DNA damage and repair in bovine lens epithelial cells. Curr Eye Res. 1990. 9:1185–1193.

5. Kojima M, Yamada Y, Sasaki K. Photo-damage and the repair process of lens epithelia cells induced by a single exposure ultraviolet light. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999. 40:B664.

6. Ayala M, Strid H, Jacobsson U, et al. p53 expression and apoptosis in the lens after ultraviolet radiation exposure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007. 48:4187–4191.

7. Andersson M, Honarvar A, Sjostrand J, et al. Decreased caspase-3 activity in human lens epithelium from posterior subcapsular cataracts. Exp Eye Res. 2003. 76:175–182.

8. Shibue T, Takeda K, Oda E, et al. Integral role of Noxa in p53-mediated apoptotic response. Genes Dev. 2003. 17:2233–2238.

9. Li WC, Spector A. Lens epithelial cell apoptosis is an early event in the development of UVB-induced cataract. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996. 20:301–311.

10. Godar DE. Preprogrammed and programmed cell death mechanisms of apoptosis: UV-induced immediate and delayed apoptosis. Photochem Photobiol. 1996. 63:825–830.

11. Hightower KR, Reddan JR, McCready JP, Dziedzic DC. Lens epithelium: a primary target of UVB irradiation. Exp Eye Res. 1994. 59:557–564.

12. Tamada Y, Fukiage C, Nakamura Y, et al. Evidence for apoptosis in the selenite rat model of cataract. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000. 275:300–306.

13. Worgul BV, Merriam GR Jr, Medvedovsky C. Cortical cataract development: an expression of primary damage to the lens epithelium. Lens Eye Toxic Res. 1989. 6:559–571.

14. Hightower K, McCready J. Physiological effects of UVB irradiation on cultured rabbit lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992. 33:1783–1787.

15. Zigman S, Vaughan T. Near-ultraviolet light effects on the lenses and retinas of mice. Invest Ophthalmol. 1974. 13:462–465.

16. Hightower K, McCready J. Comparative effect of UVA and UVB on cultured rabbit lens. Photochem Photobiol. 1993. 58:827–830.

17. Harding JJ, Crabbe MJ. Davson H, editor. The lens: development, proteins, metabolism and cataract. The eye. 1984. Vol. 1B. London: Academic Press;207–492.

18. Schuler M, Green DR. Mechanisms of p53-dependent apoptosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001. 29(Pt 6):684–688.

19. Geatrell JC, Gan PM, Mansergh FC, et al. Apoptosis gene profiling reveals spatio-temporal regulated expression of the p53/Mdm2 pathway during lens development. Exp Eye Res. 2009. 88:1137–1151.

20. Ayala M, Strid H, Jacobsson U, Soderberg PG. p53 expression and apoptosis in the lens after ultraviolet radiation exposure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007. 48:4187–4191.

21. Pokroy R, Tendler Y, Pollack A, et al. p53 expression in the normal murine eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002. 43:1736–1741.

22. Hall PA, McKee PH, Menage HD, et al. High levels of p53 protein in UV-irradiated normal human skin. Oncogene. 1993. 8:203–207.

23. Villunger A, Michalak EM, Coultas L, et al. p53- and drug-induced apoptotic responses mediated by BH3-only proteins puma and noxa. Science. 2003. 302:1036–1038.

24. Bennett M, Macdonald K, Chan SW, et al. Cell surface trafficking of Fas: a rapid mechanism of p53-mediated apoptosis. Science. 1998. 282:290–293.

25. Grabner G, Brenner W. Unscheduled DNA repair in human lens epithelium following 'in vivo' and 'in vitro' ultraviolet irradiation. Ophthalmic Res. 1982. 14:160–166.

26. Jeffers JR, Parganas E, Lee Y, et al. Puma is an essential mediator of p53-dependent and -independent apoptotic pathways. Cancer Cell. 2003. 4:321–328.

27. Oda E, Ohki R, Murasawa H, et al. Noxa, a BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family and candidate mediator of p53-induced apoptosis. Science. 2000. 288:1053–1058.

28. Qin JZ, Stennett L, Bacon P, et al. p53-independent NOXA induction overcomes apoptotic resistance of malignant melanomas. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004. 3:895–902.

29. Jullig M, Zhang WV, Ferreira A, Stott NS. MG132 induced apoptosis is associated with p53-independent induction of pro-apoptotic Noxa and transcriptional activity of beta-catenin. Apoptosis. 2006. 11:627–641.

30. Armstrong JL, Veal GJ, Redfern CP, Lovat PE. Role of Noxa in p53-independent fenretinide-induced apoptosis of neuroectodermal tumours. Apoptosis. 2007. 12:613–622.

31. Banerjee G, Gupta N, Kapoor A, Raman G. UV induced bystander signaling leading to apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2005. 223:275–284.

32. Singleton KR, Will DS, Schotanus MP, et al. Elevated extracellular K+ inhibits apoptosis of corneal epithelial cells exposed to UV-B radiation. Exp Eye Res. 2009. 89:140–151.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download