Abstract

We report a case of a retained graphite anterior chamber foreign body that was masquerading as stromal keratitis. A 28-year-old male visited with complaints of visual disturbance and hyperemia in his right eye for four weeks. On initial examination, he presented with a stromal edema involving the inferior half of the cornea, epithelial microcysts, and moderate chamber inflammation. Suspecting herpetic stromal keratitis, he was treated with anti-viral and anti-inflammatory agents. One month after the initial visit, anterior chamber inflammation was improved and his visual acuity recovered to 20/20, but subtle corneal edema still remained. On tapering the medication, after three months, a foreign body was incidentally identified in the inferior chamber angle and was surgically removed resulting in complete resolution of corneal edema. The removed foreign body was a fragment of graphite and he subsequently disclosed a trauma with mechanical pencil 12 years earlier. This case showed that the presence of an anterior chamber foreign body should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of idiopathic localized corneal edema.

Anterior chamber foreign bodies account for only up to 15% of all intraocular foreign bodies [1]. The clinical manifestations and courses of anterior chamber foreign body varies depending on its composition, shape, and reaction with adjacent structures. To date, there had been several reports describing anterior chamber foreign bodies. Some kinds of anterior chamber foreign bodies such as glasses, plastics, and even cilium are well tolerated [1-4], on the other hand, some glasses, metals, and cotton fibers induced persistent iridocyclitis or bullous keratopathy [1,5,6]. To our knowledge, there have been no reports demonstrating graphite anterior chamber foreign body that led to a late onset corneal edema and anterior chamber inflammation masquerading as herpes stromal keratitis 12 years after initial injury.

A 28-year-old male visited our department with complaint of visual disturbance, hyperemia, and epiphora in his right eye, which had developed about four weeks earlier. The patient denied previous episode of symptoms and history of keratitis or uveitis. After symptoms developed, he visited a general ophthalmologist and was prescribed 3% acyclovir ointment (5 times/day), 1% topical prednisolone acetate (8 times/day), 0.5% topical levofloxacin (8 times/day), and oral acyclovir 400 mg (1 time/day) to treat herpetic stromal keratitis. His medical and familial history was unremarkable. On initial examination, his best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/50 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure was in normal range in both eyes. Slit lamp examination of the right eye showed conjunctival hyperemia, localized edema of the central and inferior half of cornea with epithelial microcysts, and moderate anterior chamber (2+) inflammation. A focal mid-stromal scar at the temporal cornea was observed, which had not been in attention (Fig. 1).

Suspecting herpetic stromal keratitis, his medication was increased to 1% topical prednisolone acetate every one hour and oral acyclovir 400 mg five times a day while maintaining the other medications. Two weeks after the initial visit, his visual acuity decreased to 20/80 and corneal edema with microcysts were still observed. Oral prednisolone (30 mg once a day) was prescribed in addition to the other medications. After five days, anterior chamber inflammation was improv ed and his visual acuity recovered to 20/20, but subtle corneal edema and microcysts still remained (Fig. 2). At two months, he maintained 20/20 vision and his ophthalmic examination showed no significant interval changes. On tapering the medication, after three months, a previously unobserved intraocular foreign body was incidentally identified in the inferior angle of anterior chamber (Fig. 3). Thorough history taking revealed that the patient had ocular trauma with a mechanical pencil 12 years earlier.

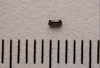

Under the operating microscope, the foreign body was surgically removed via corneal incision, which measured about 0.5 × 1.5 mm in size (Fig. 4). During the surgical procedure, the foreign body was freely movable in the chamber and there was no evidence of fibrosis or granulation reaction at the adjacent tissue. Elemental analysis of the foreign body using energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (Bruker Quantax 200; Bruker AXS, Berlin, Germany) and scanning electron microscope (Philips XL 30S FEG; Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) revealed that it consisted mainly of elementary carbon, which is compatible with the component of graphite pencil lead (Fig. 5). Two weeks after the surgery, the patient's BCVA was 20/15, and remaining corneal edema and microcysts were completely resolved (Fig. 6). Specular microscopy showed that endothelial cell density was reduced following the event, but the percentage of hexagonal cells increased after removal of the foreign body (Fig. 7).

There are few reports of graphite foreign bodies in ocular structures. Two cases of retained graphite in the vitreous have been reported. There was no inflammatory reaction during six years of follow-up in one case [7], while endophthalmitis developed two days after trauma in the other case. The authors mentioned the possibility of infectious endophthalmitis or sterile endophthalmitis caused by elemental aluminum released by the retained graphite fragment [8]. There are also cases of retained graphite in the conjunctiva simulating melanoma [9], and intracorneal graphite particles, which were well tolerated [10].

In this case, the foreign body which had penetrated 12 years earlier, did not show any cellular adhesion or pigment precipitation on its surface, thus a graphite foreign body seems to be well tolerated in the anterior chamber without inducing any foreign body reactions or inciting ocular inflammation. Moreover, given the response to surgical removal of the foreign body, the patient's manifestations, such as corneal edema and inflammatory response on initial visit, should be attributed to mechanical irritation of the adjacent tissues including the iris and corneal endothelium. Based on the absence of ocular symptoms for 12 years, we may assume that the foreign body had remained in a place where it did not contact the corneal endothelium. A certain event such as minor trauma could have dislodged the foreign body from the original place, and resulted in corneal edema by irritating the corneal endothelium.

When a young patient presents with unilateral corneal stromal edema and anterior chamber inflammation, differential diagnosis should include glaucomatocyclitic crisis, herpes stromal keratitis, and intraocular foreign body. In this case, although the patient had a history of ocular trauma, it was 12 years earlier, and no evidence of intraocular foreign body except an old focal corneal scar was observed at the first visit. He also revealed normal intraocular pressure, and was therefore treated with anti-virals and anti-inflammatory agents to treat herpetic stromal keratitis.

The proper diagnosis and treatment were delayed until the foreign body was detected through the course of follow-up examination. The anti-inflammatory effect of medication or spontaneous interaction with adjacent tissue of the foreign body would explain the moderate response to steroid treatment during follow-up. Persistent corneal problems indicate that there had been intermittent mechanical contact of the foreign body with the corneal endothelium. Complete resolution of corneal edema and epithelial microcysts was achieved only after surgical removal of the graphite foreign body from the anterior chamber.

Careful history taking and meticulous slit lamp examination would have led to the proper management earlier. This case showed that localized corneal stromal edema or endothelial dysfunction can be caused by an intraocular foreign body, even with history of trauma that occurred much earlier. A physician should always arouse suspicion and perform a thorough examination, including gonioscopy, in such patients.

Figures and Tables

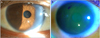

Fig. 1

A slit lamp biomicroscopic finding on the patient's initial visit revealed conjunctival hyperemia, localized corneal stromal edema with epithelial microcysts, and moderate chamber inflammation. A focal mid-stromal scar at the temporal cornea was also noted.

Fig. 2

After five days of steroid treatment, stromal edema was decreased and the patient's vision improved to 20/20. Localized epithelial microcysts were still observed.

Fig. 3

At three months after initial visit, a previously unobserved foreign body was incidentally identified in the inferior angle of anterior chamber.

Fig. 5

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy of the removed foreign body revealed that it contains mainly elementary carbons, which implies that the foreign body is a broken graphite pencil lead.

Fig. 6

Two weeks after removal of the foreign body, the previous corneal stromal edema and epithelial microcysts were completely resolved.

Fig. 7

Specular microscopy findings before (A) and two weeks after (B) the surgery. Corneal endothelial cell density reduced following the episode of corneal edema, but the percentage of hexagonal cells improved from 35% to 44% after removal of the foreign body. APEX = apex; AVE = average; MAX = maximum; MIN = minimum; NUM = number; CD = cell density; SD = standard deviation; CV = coefficient of variation; 6A = hexagonality.

References

1. Archer DB, Davies MS, Kanski JJ. Non-metallic foreign bodies in the anterior chamber. Br J Ophthalmol. 1969. 53:453–456.

2. Kim JH, Park KS. A case of eye lashes in an anterior chamber. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1968. 9:23–25.

3. Chang YS, Jeong YC, Ko BY. A case of an asymptomatic intralenticular foreign body. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2008. 22:272–275.

4. Kargi SH, Oz O, Erdinc E, et al. Tolerated cilium in the anterior chamber. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2003. 11:73–78.

5. Stangos AN, Pournaras CJ, Petropoulos IK. Occult anterior-chamber metallic fragment post-phacoemulsification masquerading as chronic recalcitrant postoperative inflammation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005. 139:541–542.

6. Brown SI. Corneal edema from a cotton foreign body in the anterior chamber. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968. 65:616–617.

7. Honda Y, Asayama K. Intraocular graphite pencil lead without reaction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985. 99:494–495.

8. Hamanaka N, Ikeda T, Inokuchi N, et al. A case of an intraocular foreign body due to graphite pencil lead complicated by endophthalmitis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1999. 30:229–231.

9. Guy JR, Rao NA. Graphite foreign body of the conjunctiva simulating melanoma. Cornea. 1985-1986. 4:263–265.

10. Jeng BH, Whitcher JP, Margolis TP. Intracorneal graphite particles. Cornea. 2004. 23:319–320.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download