Abstract

We report a case of one sister and brother with mirror image myopic anisometropia. One sister and brother complained visual disturbance. The sister was 10 years 11 months old, and brother was 8 years 4 months old. Full ophthalmic examinations were performed, including slit lamp examination, intraocular pressure, keratometry, anterior chamber depth, axial length, fundus examination and the cycloplegic refraction. The cycloplegic refractive power was -15.50 dpt cyl.+4.50 dpt Ax 85° (right eye), -1.00 dpt cyl.+0.50 dpt Ax 90° (left eye) in the sister; -1.75 dpt cyl.+2.25 dpt Ax 90° (right eye), -9.50 dpt cyl.+4.00 dpt Ax 80° (left eye) in the brother. The co-occurrence of severe myopic anisometropia in a sister and brother is extremely rare. The present case suggests that severe myopic anisometropia may be related by genetic inheritance.

Anisometropia, by definition, exists when there is a difference in refractive status between an individual's two eyes. Variable refractive combinations and degrees of imbalance are possible. The possible determining factors for anisometropia remain obscure. The prevalence of anisometropia (more than 3.0 diopters) in toddlers and young children ranges between 1% and 8.1% [1-4].

Previous studies had reported that monozygotic twins have revealed concordances in the refractive power, axial length, corneal curvature, and cup-to-disc ratio, thereby suggesting that genetic factors mat be related to myopic anisometropia. The hereditary concordance in monozygotic twins is higher than in dizygotic twins [5], showing the genetic element of myopic anisometropia.

Because of the rarity of myopic anisometropia, the genetic element of this disorder has not been studied in siblings until now. Herein, we report a sister and brother with mirror image anisometropia.

At the first medical examination, the sister was 7 years 8 months old, and the brother was 5 years 3 months old. Neither sibling had any specific birth history. Slit lamp microscopic examination revealed no abnormalities in the anterior segments of either eye, in either patient. Fundoscopic examination revealed no abnormalities. No abnormal ocular movements were demonstrated.

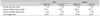

The best corrected visual acuities (BCVA) were 0.1 (right eye) and 0.8 (left eye) in the sister, and 0.7 (right eye) and 0.1 (left eye) in the brother. The cycloplegic refractive powers in the sister were: -15.50 diopter (dpt), cylinder (cyl) +4.50 dpt Ax 85° in the right eye and -1.00 dpt cyl. +0.50 dpt Ax 90° in the left eye. The cycloplegic refractive powers in the brother were: -1.75 dpt cyl. +2.25 dpt Ax 90° in the right eye and -9.50 dpt cyl. +4.00 dpt Ax 80° in the left eye (Table 1). The differences in spherical equivalents between the two eyes were -12.50 diopters in the sister and -6.875 diopters in the brother.

Full-time right occlusion therapy was performed in both patients for three months, then four to six hours a day for two years. The brother maintained a right occlusion on the weekends. The sister was prescribed atropine for the left eye after six hours right-sided occlusion therapy a day for a year. Three years later, the BCVA in the brother's left eye had improved from 0.1 to 0.7. The BCVA in the sister's left eye improved from 0.1 to 0.7 during the first year; however, she showed no further improvement after that time. The refractive powers in the sister were changed to -12.50 dpt cyl. +4.00 dpt Ax 80° in the right eye and -4.50 dpt cyl. +0.75 dpt Ax 90° in the left eye. The refractive powers in the brother were changed to -5.00 dpt cyl. +3.50 dpt Ax 95° in the right eye and -11.50 dpt cyl. +4.00 dpt Ax 85° in the left eye. The refraction and the radius of the anterior corneal curvature were measured using an autorefractokeratometer (Speedy-K; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and a topographer (ORB-scan; Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY, USA). The anterior corneal curvature was calculated using the average horizontal and vertical values. A-mode ultrasonography (Cinescan; Quantel Medical, Clermont-Ferrand, France) was performed. The results of A-mode ultrasonography and ORB-scan are presented in Table 2.

Anisometropia is a difference in the refractive error between an individual's two eyes. This condition is often associated with amblyopia, both in the presence of and in the absence of strabismus [6, 7]. The prevalence of anisometropia reported in school-based and population-based studies of school-aged children is typically 5%, but this figure varies depending on the manner in which anisometropia is defined [8].

Myopic anisometropia is a rare type of anisometropia. Myopic anisometropia is usually accompanied by strabismus, especially exotropia in 30-60% of patients. The incidence of exotropia is independent of the degree of anisometropia. This suggests that the development of binocular vision might be affected by mild infantile exotropia [9]. However, in this report, neither the sister nor the brother had exotropia.

Myopic anisometropia with intact near vision seldom results in amblyopia. If ordinary vision is defocused due to high myopia, refractive amblyopia may occur. When high myopia of one eye is more than -5 to -6 diopters, or the difference in spherical equivalents of both eyes is more than 5 diopters, then anisometropia may be responsible for amblyopia [10]. The sister and brother in this study had anisometropic amblyopia. However, the amblyopia responded well to occlusion therapy. As shown in Table 1, compared with the report of Okamoto et al. [9], the present case is without any obvious complication and shows mirror image similarly.

In the study of 78 monozygotic twins and 40 dizygotic twins, Sorsby et al. [11] reported that the concordances of corneal power, axial length, and vertical ocular refraction were higher in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins. Such findings indicate that the refractive power and particular myopia are influenced by heredity. Interestingly, patients in the present study had similar axial lengths in their myopic eyes.

In conclusion, the co-occurrence of severe myopic anisometropia in siblings is extremely rare. We believe that severe myopic anisometropia may be genetically determined, and further investigation is recommended. Myopic anisometropic amblyopia responds well to occlusion therapy.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Abrahamsson M, Fabian G, Sjŏstrand J. Changes in astigmatism between the ages of 1 and 4 years: a longitudinal study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988. 72:145–149.

2. Abrahamsson M, Fabian G, Sjŏstrand J. A longitudinal study of a population based sample of astigmatic children. II. The changeability of anisometropia. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1990. 68:435–440.

3. Abrahamsson M, Fabian G, Andersson AK, Sjŏstrand J. A longitudinal study of a population based sample of astigmatic children. I. Refraction and amblyopia. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1990. 68:428–434.

4. Abrahamsson M, Sjŏstrand J. Natural history of infantile anisometropia. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996. 80:860–863.

5. Teikary JM, O'Donnell J, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M. Impact of heredity in myopia. Hum Hered. 1991. 41:151–156.

6. von Noorden GK. Amblyopia: a multidisciplinary approach. Proctor lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985. 26:1704–1716.

7. Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of atropine vs. patching for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002. 120:268–278.

8. Almeder LM, Peck LB, Howland HC. Prevalence of anisometropia in volunteer laboratory and school screening populations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990. 31:2448–2455.

9. Okamoto F, Nonoyama T, Hommura S. Mirror image myopic anisometropia in two pairs of monozygotic twins. Ophthalmologica. 2001. 215:435–438.

10. Rosenthal AR, von Noorden GK. Clinical findings and therapy in unilateral high myopia associated with amblyopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971. 71:873–879.

11. Sorsby A, Sgeridan M, Leary GA. Refraction and its components in twins. 1962. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office;1–43.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download