Abstract

A 53-year-old woman visited the Department of Rheumatology with a chief complaint of a 3-day history of fever and chills and also presented with pain occuring in both knees at the time of outpatient visit. Based on rheumatologic and hematological lab studies, ultrasonography, and a needle aspiration biopsy of the articular cavity, the patient was diagnosed with reactive arthritis. On hospitalization day 3, consultation with the Department of Ophthalmology was requested regarding decreased visual acuity lasting for 3 days. Upon ophthalmologic examination, the corrected visual acuity was 0.1 in the right eye and 0.05 in the left eye. Upon slit lamp microscopy, there were no abnormal findings in the anterior segment. Upon fundus examination, however, there were yellow-white lesions in the macular area of both eyes. Fluorescein angiographywas performed to assess the macular lesions, and the findings were suggestive of macular infarction in both eyes. Due to a lack of other underlying disease, a past surgical history, and a past history of drug administration, the patient was diagnosed with macular infarction in both eyes associated with reactive arthritis. To date, there have been no other such cases reported. In a patient with reactive arthritis, we experienced a case of macular infarction in both eyes, which occurred without association with a past history of specific drug use or underlying disease. Herein, we report our case, with a review of the literature.

Reactive arthritis is an acute nonpurulent arthritis that develops from complications following the infection of other body areas and can occur due to various bacterial causes [1]. It is well known that reactive arthritis occurs due to the provocation of autoimmune responses because of sexual contact or bacterial infection via the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. To date, however, its overall pathophysiology has not been clarified.

In 1986, Lee et al. [2] reported that the ophthalmic manifestations were present in 58% of 113 patients with reactive arthritis. Conjunctivitis was the most commonly reported ophthalmic manifestation of reactive arthritis. The occurrence of uveitis has also been reported in association with reactive arthritis [3]. In these cases, permanent loss of visual acuity can also occur. Other ophthalmic manifestations, such as keratitis, cataract, glaucoma, macular edema, papillitis, and scleritis have also been reported [3]. To date, however, no cases have been reported of reactive arthritis associated with macular infarction.

In association with sickle cell disease, the use of dapsone, snake venom poisoning, the concomitant use of photodynamic therapy and an intravitreal injection of triamcinolone, an intravitreal injection of ganciclovir and an intravitreal injection of amikacin, the occurrence of macular infarction has been reported [4-9]. In a patient with reactive arthritis, who complained of the decreased visual acuity in both eyes, we experienced a case of macular infarction. Herein, we report our case, with a review of the literature.

A 53-year-old woman visited the Department of Rheumatology with the chief complaint of a 3-day history of fever and chills and also presented with pain occuring in both knees at the time of the outpatient visit. The patient's past history included no notable medical and surgical findings. Upon hematology performed following the hospitalization, the parameters were elevated to WBC 14,730/mm2, ESR 55 mm/hr, and CRP 13.29 mg/dL. Such negative results as ANA 1:80 (+), lupus anticoagulant 1.6, and HLA B27 were also reported. A blood culture test was also negative. Upon ultrasonography, a great amount of the effusion was present within the articular cavity. A fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the intra-articular cavity showed that the WBC count was increased to 900/mm3. No other abnormal laboratory findings than these findings were noted. Based on these findings and ruling out other rheumatic diseases, a diagnosis of reactive arthritis was made.

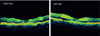

On hospitalization day 3, consultation with the Department of Ophthalmology was requested regarding decreased visual acuity lasting for 3 days. Upon ophthalmic examination, her corrected visual acuity was 0.1 in her right eye and 0.05 in her left eye. Intraocular pressure was 12 mmHg in both eyes. Upon slit lamp microscopy, there were no abnormal findings in the anterior segment. Upon fundus exam, however, there were yellow-white lesions in the macular area of both eyes (Fig. 1). Optical coherence tomography (Stratus OCT; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Oberkochen, Germany) of both eyes revealed the hyperreflectivity of the inner retina (Fig. 2). Upon fluorescein angiography, the avascular area of the fovea was markedly enlarged (Fig. 3). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with macular infarction in both eyes. Due to a lack of other causative factors, such as other underlying diseases, a past surgical history, a past history of ophthalmic trauma, and a past history of drug administration, the patient was diagnosed with macular infarction in both eyes associated with reactive arthritis.

After 4 weeks, corrected visual acuity was 0.1 (-1) in her right eye and finger count discrimination occurred in her left eye.

Reactive arthritis is a joint disease associated with HLA-B27, which also occurs in association with GI tract infections or urogenital tract infections. A cell-mediated immunity is induced by the infectious pathogenic antigens. It has been postulated that the antigen-specific CD4 T-cells and CD8 T-cells are activated within the articular cavity, and this causes the inflammatory response within the tissue. It causes the inflammations in such areas as the joints, insertions of tendons, skin, mucosa, GI tract, and eyes.

Such ophthalmic manifestations as conjunctivitis or uveitis have been commonly reported to occur in association with the concurrent presence of ophthalmic problems [3]. To date, however, there are no cases of macular infarction which has been developed in association with reactive arthritis.

Macular infarction can develop due to these hematological problems. In sickle cell anemia, sickle-shaped RBCs increase the blood viscosity and thereby can trigger such symptoms as vascular obstruction, ischemia, hypoxia, and tissue necrosis [4]. Snake venom can also cause tissue necrosis because of the derangement of blood coagulation cascades [6]. By contrast, macular infarction due to dapsone or amikacin occurs as a result of the drug toxicity itself [5,9].

In our case, however, there were no causative factors that have previously been reported to be related to macular infarction. However, one of the causative factors, if any, for macular infarction in this case would be the increased level of lupus anticoagulant, one of the anti-phospholipid antibodies, among laboratory findings. Based on these laboratory findings, it can be inferred that this case is associated with anti-phospholipid syndrome.

Antiphospholipid syndrome is a disorder characterized by a wide variety of clinical manifestations. Virtually any organ system or tissue may be affected by the consequences of large- or small-vessel thrombosis. A broad spectrum of disease exists among individuals with antiphospholipid antibodies [10].

A review of the literature found a correlation between reactive arthritis and antiphospholipid syndrome [11]. It has also been reported that such ophthalmic manifestations as ocular ischemic syndrome, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, central retinal vein occlusion, branched retinal vein occlusion, and retinal vasculitis have occurred in association with antiphospholipid syndrome [12]. Also, in our case, the serum level of lupus anticogulant was elevated upon laboratory tests. It is probable that macular infarction occurred due to macular thrombosis, because the increased level of lupus anticoagulant exacerbated the mechanisms of blood coagulation. However, other than the elevated level of lupus anticoagulant, such laboratory findings associated with blood coagulation as prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time were all normal. Besides, the patient had no past history of thrombosis. Therefore, our patient's case could not meet all of the criteria for a diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome. Still, although rare, a greater number of cases will be needed to establish the causal relationship between the two diseases.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Carter JD. Reactive arthritis: defined etiologies, emerging pathophysiology, and unresolved treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006. 20:827–847.

2. Lee DA, Barker SM, Su WP, et al. The clinical diagnosis of Reiter's syndrome. Ophthalmic and nonophthalmic aspects. Ophthalmology. 1986. 93:350–356.

3. Kiss S, Letko E, Qamruddin S, et al. Long-term progression, prognosis, and treatment of patients with recurrent ocular manifestations of Reiter's syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2003. 110:1764–1769.

4. Merritt JC, Risco JM, Pantell JP. Bilateral macular infaction in SS disease. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1982. 19:275–278.

5. Hussain N, Agrawal S. Optical coherence tomograhic evaluation of macular infarction following dapsone overdose. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2006. 54:271–272.

6. Singh J, Singh P, Singh R, Vig VK. Macular infarction following viperline snake bite. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007. 125:1430–1431.

7. Lo Giudice G, De Belvis V, Piermarocchi S, et al. Acute visual loss and chorioretinal infarction after photodynamic therapy combined with intravitreal triamcinolone. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2008. 18:652–655.

8. Kim SW, Oh J, Huh K. Macular infarction after intravitreal ganciclovir injection in a patient with acute retinal necrosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008. 43:124–125.

9. Galloway G, Ramsay A, Jordan K, Vivian A. Macular infarction after intravitreal amikacin: mounting evidence against amikacin. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002. 86:359–360.

10. Baker WF Jr, Bick RL. The clinical spectrum of antiphospholipid syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008. 22:33–52.

11. Tamura N, Kobayashi S, Hashimoto H. Anticardiolipin antibodies in patients with post-streptococcal reactive arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002. 61:374.

12. Suvajac G, Stojanovich L, Milenkovich S. Ocular manifestations in antiphospholipid syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2007. 6:409–414.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download