Abstract

A 64-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for the treatment of chronic uveitis in her left eye, which had started two weeks after an uncomplicated cataract extraction. She was treated with topical steroids with an initially good response, yet she subsequently developed severe inflammation and plaque-like material around the intraocular lens, despite continuous steroid therapy. She underwent pars plana vitrectomy, smear and culture of the aqueous and vitreous fluids, and intravitreal antibiotic injection under the impression of Propionibacterium acne (P. acne) endophthalmitis. As a result of the smear and culture of the vitreous fluid identified as an Acremonium species, she was treated with intravenous amphotericin B injections for five days, followed by oral voriconazole administration. During the post-operative 18-month follow-up, she was stable without significant relapse of uveitis. In this case, the best correction of visual acuity was an improvement from 20/40 to 20/20.

There are many known etiologies of endophthalmitis after cataract extraction surgery. Among them, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Propionibacterium acne (P. acne), and various fungi are known to be major causes of delayed-onset endophthalmitis [1]. Acremonium was reported as a rare cause of delayed post-cataract surgery endophthalmitis in 12 previous reports. To the best of our knowledge, however, Acremonium endophthalmitis has never been reported in Korea.

We, herein, describe an unusual case of Acremonium endophthalmitis which developed two weeks after cataract surgery in a female patient.

A 64-year-old woman presented with chronic, waxing and waning uveitis in her left eye. She had undergone phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation in that eye at a local clinic nine months prior. Two weeks after surgery, mild anterior chamber inflammation developed. At first, the inflammation was well controlled with steroid eye drops. Over time, however, the inflammation repeatedly recurred. Whenever the patient stopped using steroid eye drops or when her general condition deteriorated, her left eye experienced anterior chamber inflammation. After nine months, she was referred to our clinic.

On initial examination in our clinic, her best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/25 in both eyes. Slit-lamp examination revealed grade 3 anterior chamber inflammation and mild vitreous opacity in the left eye. She was diagnosed with chronic uveitis and was prescribed steroid eye drops.

After seven weeks of steroid therapy, the inflammation worsened, and her visual acuity decreased to 20/40. On biomicroscopic examination, the anterior chamber inflammation had increased to grade 4, and plaque-like material was noted around the intraocular lens in the left eye. A fundus photograph showed mild vitreous opacity obscuring the fundus detail (Fig. 1). Laboratory tests, including complete blood cell count, a treponemal antibody test, rheumatoid factor measurement, an antistreptolysin O test, and measurement of autoimmune antibody, were all negative, except for a slightly increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

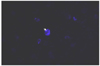

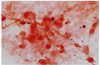

Pars plana vitrectomy along with a smear and culture of the aqueous and vitreous fluids was conducted, as delayed-onset chronic infectious endophthalmitis caused by P. Acne or fungus was suspected. The plaque-like material along the posterior lens capsule was removed as much as possible, but the intraocular lens was left in place since the patient strongly wi shed to maintain her pseudophakic state. At the end of vitrectomy, 10 µg/0.1 mL amphotericin B, 1 µg/0.1 mL vancomycin, and 2 µg/0.1 mL ceftazidime were injected into the vitreous. Examination of the vitreous fluid revealed WBCs and septated fungal hyphae of an Acremonium species in both KOH-Calcofluor staining (Fig. 2) and Gram-staining (Fig. 3). With a diagnosis of Acremonium-related endophthalmitis, intravenous ampotericin B was given daily for post-operative five days. The patient was then discharged with directions to take oral voriconazole medication for four weeks.

One month after the vitrectomy, the patient's best corrected visual acuity improved to 20/30 and the anterior chamber inflammation was reduced to grade 1. The thin plaque-like material around the intraocular lens (Fig. 4) that was noticed at the immediate postoperative period gradually decreased over time with extended oral antifungal treatment for six months. Eighteen months later, the best corrected visual acuity had improved to 20/20 and the anterior chamber inflammation had disappeared.

Our patient represents an interesting case of delayed-onset post-operative Acremonium endophthalmitis that presented as chronic recurrent uveitis.

Although less frequent than acute endophthalmitis, delayed-onset, chronic, recurrent endophthalmitis may occur following cataract surgery, mostly due to unusual bacterial or fungal infection. This type of chronic endophthalmitis is initially often misdiagnosed as chronic uveitis and treated with steroids. However, eventually inflammation develops and requires further diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

A unique clinical feature of chronic recurrent inflammation is a white plaque-like material deposition around the intraocular lens, as seen in our patient, often presenting as P. acne endophthalmitis [2]. Therefore, we initially suspected P. acne as the causative agent. However, fungal infection may also show similar clinical features [1-2]. We also conducted a smear and culture to determine whether fungus was a possible infectious source.

Fortunately, we were able to identify Acremonium hyphae from the vitreous fluid stained with KOH-Calcofluor stain (Fig. 2) and Gram-stain (Fig. 3).

Acremonium species, formerly termed Cephalosporium species, are soil fungi that are ubiquitous environmental contaminants [2-5]. They are saprophytic molds and have septate colorless hyphae like those of other hyaline molds [6]. Although invasive disease may occur in an immunocompromised person, usually most cases of human disease occur in immunocompetent hosts, unlike with other filamentous fungi [6]. Most cases of infection are mycetomas of the extremities in patients in the tropics [6].

Ocular involvement of Acremonium is uncommon. Exogenous fungal endophthalmitis is known to occur in a variety of clinical settings including contiguous spread of fungal keratitis, after penetrating keratoplasty, after retinal detachment surgery, with intraocular inoculations from irrigation solutions, and so on [3]. Also, Acremonium may postoperatively invade through wounds. Air contaminated solutions such as humidifier fluid or contaminated objects are also possible sources [5].

The initial presenting symptoms of Acremonium endophthalmitis are similar to those of most delayed-onset fungal endophthalmitis, including mild pain, redness, floaters and slightly decreased visual acuity [2-5,7]. The time interval between cataract operation and endophthalmitis ranges from 12 days to six weeks, but is usually one month [2-5,7]. Interestingly, Acremonium infection may mimic Propionibacterium infection in that both organisms yield similar plaque-like materials in and around the anterior chamber [2-4]. Cameron et al. [4] reported that they had observed inflammatory multinucleated giant cells and slender septated fungal hyphae in the histopathologic specimen of the white plaque from an Acremonium endophthalmitis patient.

The definitive identification of Acremonium requires a culture, but it can be identified provisionally in tissue sections through the presence of a combination of histologic features, including hyaline septate hyphae and characteristic reproductive structures known as phialides and phialoconidia [6]. The best stains for observing fungi are Grocott methenamine-silver and Giemsa stains [8]. But Gram stain and 10% potassium hydroxide are still used as an alternative method for identifying fungal organisms [8]. In our cases, Gram staining of the vitreous sample showed Acremonium hyphae.

To date, a treatment modality has not been well established for these fungal infections. In a four-case series report, Weissgold et al. [3] suggested that higher drug doses or repeated dosing with amphotericin B (possibly in combination with vitrectomy) may be necessary to adequately treat such infections. Cameron et al. [4] reported that Acremonium remains viable in the anterior chamber despite surgical removal of the bulk of the fungal mass and treatment with several antifungal medications, including topical natamycin, topical amphotericin B, subconjunctival miconazole injection, and oral ketoconazole. In our case, the remaining white plaque in the anterior chamber after vitrectomy was treated with voriconazole medication for six months. Voriconazole is a triazole derivative that achieves a sufficient therapeutic level in aqueous and vitreous liquids by oral administration [1,9,10]. Mattei et el. [10] reported that voriconazole treatment appeared to be very effective in their case report of fungemia caused by Acremonium.

With the recent advances of vitreous surgical technique, including sutureless vitrectomy and a panoramic viewing system, vitrectomy is more widely accepted as a treatment option for chronic recurrent endophthmitis [11]. Especially when a significant vitreous opacity is associated, as in our case, vitrectomy is preferred over vitreous tap and intravitreal injection.

In conclusion, we report a unique case of chronic postoperative endophthalmitis with plaque-like material that was diagnosed as an uncommon Acremonium endophthalmitis. Like most cases of fungal infection or P. acne endophthalmitis, combined therapy with vitrectomy and long-term antifungal medication produced a good visual outcome.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Fundus photograph at the time of presentation. The left eye is hazy due to vitreous opacity (right). |

| Fig. 2KOH-Calcofluor staining of vitreous fluid obtained during pars plana vitrectomy H & E, ×400. Septum of fungal hyphae (white arrow). |

References

1. Meredith TA. Ryan SJ, Hinton DR, Schachat AP, Wilkinson CP, editors. Vitrectomy for infectious endophthalmitis. Retina. 2006. Vol. 3:4th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby;2260–2261.

2. Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, Miller D. Delayed-onset endophthalmitis following cataract surgery caused by Acremonium strictum. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2005. 36:506–507.

3. Weissgold DJ, Maguire AM, Brucker AJ. Management of postoperative Acremonium endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1996. 103:749–756.

4. Cameron JA, Badawi EM, Hoffman PA, Tabara KF. Chronic endophthalmitis caused by Acremonium falciforme. Can J Ophthalmol. 1996. 31:367–368.

5. Fridkin SK, Kremer FB, Bland LA, et al. Acremonium kiliense endophthalmitis that occurred after cataract extraction in an ambulatory surgical care and was traced to an environmental reservoir. Clin Infect Dis. 1996. 22:222–227.

6. Fleming RV, Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ. Emerging and less common fungal pathogens. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002. 16:915–933.

7. Vescia N, Cavarischia R, Valente A, et al. Case report. Multiple etiology post-surgery endophthalmitis. Mycoses. 2002. 45:41–44.

8. Weissgold DJ, Orlin SE, Sulewski ME, et al. Delayed-onset fungal keratitis after endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1998. 105:258–262.

9. Wang MX, Shen DJ, Liu JC, et al. Recurrent fungal keratitis and endophthalmitis. Cornea. 2000. 19:558–560.

10. Mattei D, Mordidni N, Lo Nigro C, et al. Successful treatment of Acremonium fungemia with voriconazole. Mycoses. 2003. 46:511–514.

11. Lemiley CA, Han DP. Endophthalmitis: a review of current evaluation and management. Retina. 2007. 27:662–680.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download