Abstract

We describe two cases of branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) after carotid artery (CA) stenting.

Case 1: A 57-year-old man diagnosed with left neovascular glaucoma was admitted to our department for trabeculectomy (He had complained of decreased visual acuity (VA) in the left eye for a month). A preoperative neck angio CT scan showed bilateral CA stenosis. After CA stenting, he contracted visual defects on the right superior area of his right eye. Upon examination, VA with correction was found to be 1.0 (OD), but right fundoscopy revealed ischemic retina whitening along the inferior temporal arcade.

Case 2: A 64-year-old man received left CA stenting for severe stenosis in the Department of Neurology. The next day, he was referred to us for acute onset of a left naso-inferior visual field defect. Upon initial examination, his VA with correction was 0.8/0.16 (OD/OS) and fundoscopy revealed ischemic retina whitening at the superior posterior pole in the left eye.

It was not necessary to treat the BRAO in these cases because the foveal capillary network was not invaded at 2 month follow ups, VA was preserved in both cases.

In conclusion, ophthalmic evaluation is important after CA stenting because of a possible embolic occlusion of the retinal artery.

Embolisms from the carotid bifurcation have been described as the most common cause of central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) and branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO). Other causes of CRAO and BRAO include cardiac disease, retinal artery thrombosis, vascular spasm, and vasculitis.1 Carotid angioplasty and stenting has become increasingly accepted as an alternative therapy to endarterectomy for treatment of embologenic carotid artery bifurcation lesions.2 We report two cases of branch retinal arterial occlusion after carotid artery stenting in the carotid stenosis.

A 57-year-old man was referred to our department for decreased visual acuity in the left eye that had lasted for one month. Prior to admission, he was diagnosed with diabetic retinopathy in both eyes and underwent one laser treatment in the left eye at a local clinic. His medical history revealed that he had suffered a left cerebral infarction 1 year ago. Our department planned to treat him with a trabeculectomy for neovascular glaucoma in his left eye. He had experienced amaurosis fugax in the left eye and a fluorescein angiogram revealed mild diabetic retinopathy in the left eye, while the right eye was normal. We diagnosed ischemic ocular syndrome in the left eye, and a preoperative neck angio CT scan showed bilateral carotid artery stenosis (Fig. 1A) and obstruction of the left middle cerebral artery. He was transferred to the Department of Neurology and received a bilateral carotid artery stent. The next day, he presented with a superior visual field defect in his right eye. Upon examination, the Snellen acuity with correction was 1.0 in the right eye with FC 20 cm in the left eye with an intraocular pressure (IOP) of 13/32 mmHg. Right fundoscopy revealed ischemic retina whitening along the inferior temporal arcades sparing the fovea. A fluorescein angiogram showed choroidal hypoperfusion and no filling of the retinal artery or vein in the inferotemporal posterior pole (Fig. 1C). The visual field defect involved the superior nasal quadrant and partial superior temporal field in the right eye (Fig. 1D).

Two months later, right corrected visual acuity was 1.0, while the right visual field recovered slightly after that.

A 64-year-old man received left carotid artery stent insertion for severe left carotid artery stenosis (Fig. 2A) in the Department of Neurology. He had not experienced ocular symptoms in either eye before insertion of the stent. The following day, he complained of acute onset of a left naso-inferior visual field defect. On initial examination, his visual acuity with correction was 0.8/0.16 (OD/OS) and the IOP was 18/15 mmHg. The visual field defect involved the inferior nasal quadrant field and partial inferior temporal field in the left eye. Left fundoscopy revealed ischemic retina whitening at the superior posterior pole except for the fovea (Fig. 2B). A fluorecein angiogram showed delayed filling and the emboli in the superior temporal artery of his right eye (Fig. 2C). He was treated with anticoagulant medication in Neurology and was observed in Ophthalmology.

Two months later, the right visual acuity and the visual field defect had not changed.

Karjalainen3 found that the incidence of CRAO is less than 1/1000, while BRAO is also a fairly rare ocular condition, occurring about one-third as frequently as CRAO. The mean age of onset of BRAO is 62 years (both sexes), but is 58 for men alone and 67 for women.4 Men suffer retinal artery occlusion more often than women in a ratio of about 4:3.4 In our cases, the patients were 57 and 64 year-old men.

The origin of BRAO is almost always embolic as compared to the origin of CRAO, which can be thrombolic or embolic. Such emboli have been found to consist of endogenous materials (cholesterol, calcium, platelets, fibrins, lipids or tumors), pathogenic organisms (bacteria, parasites, or fungi), or several exogenous substances injected intravenously for diagnostic, therapeutic, or recreational reasons.5,6 In these cases, we propose that the retinal artery was obstructed by an embolus, as the symptoms occurred just one day after insertion of a carotid stent.

When retinal artery occlusion occurs, it usually indicates a significant underlying systemic disease or variable treatments and procedures related to that disease. Although carotid artery stenosis is commonly associated with retinal artery occlusion, many other conditions can also be associated with this problem: diffuse obliterative arteritis, hypertension, cardiac valvular disease, arterial myxomas, retinal atherosis, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular accidents, blood dyscrasias, collagen vascular disease, migraines, temporal arteritis, embolisms, etc.4,7,8 Besides these systemic diseases, retinal artery occlusions can be the result of other treatments and procedures, including carotid angiography, supraophthalmic carotid injection of anticancer drugs, and the injection of steroids into the nasal cavity or a chalazion.9 In our cases, though, the patients suffered from systemic diseases, the direct cause of the retinal artery occlusion was most likely the carotid stent procedure, as the patients complained of ocular symptoms immediately following the procedure.

Wilentz et al.2 evaluated 118 sequential patients who underwent carotid stenting. Retinal embolization occcurred in 6 patients (14%), of whom 2 were symptomatic (1.7%). Using transcranial Doppler (TCD) measurements in 40 patients, Jodan et al. found a significant number of embolic episodes during carotid angioplasty and stenting, with a mean of 74.0 emboli per procedure and four total neurologic events.10 Our results cannot be directly compared with this study, however, because we did not have a sufficient number of cases.

Patients can be treated with one of the three basic therapeutic modalities: combined acute and chronic measures, chronic measures only, or observation only. Acute treatment included modalities that lowered intraocular pressure and enhanced retinal oxygenation, such as anterior chamber paracentesis, ocular massage, systemic acetazolamide, topical timolol maleate, and 5% carbon dioxide, 95% oxygen inhalation. Chronic treatments are directed towards decreasing platelet adhesiveness through the use of aspirin, dipyridamole or sulfinpyrazone.5 In our cases, the patients were treated with anticoagulant drugs (aspirin 100 mg/day, clopidogrel 75 mg/day continually, nadroparine 2,850 IU/day for 5 days). After 2 months, visual acuity was maintained and the visual field defect was improved in case 1, but in case 2, both visual acuity and the visual field defect did not change.

Ophthalmic evaluation is very important after carotid artery stent insertion because of possible embolic occlusion of the retinal artery. Patients must be advised of the risk of permanent vision loss as a result of carotid artery stenting.

Figures and Tables

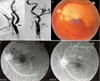

Fig. 1

(A) Trans-femoral carotid angiography shows bilateral partial occlusion of the internal carotid artery at the proximal branching portion (arrow). (B) The red-free photograph of fundus shows ischemic retina whitening at the inferior posterior pole except the fovea. (C) The fluorescein angiogram at 30 seconds after dye injection shows choroidal hypoperfusion and no filling of the retinal artery or vein in inferotemporal posterior pole. (D) The visual field test shows visual defects of the superior nasal quadrant and the superior temporal field in the right eye.

Fig. 2

(A) Trans-femoral carotid angiography shows partial occlusion of the left internal carotid artery at the proximal branching portion (arrow). (B) The color photograph of fundus shows ischemic retina whitening at the superior posterior pole except the fovea. (C) The fluorecein angiogram shows delayed filling (black arrows), embol (white arrows) and perivascular leaking in the superior temporal artery of the left eye.

References

1. Kimura K, Hashimoto Y, Ohno H, et al. Carotid artery Disease in Patients with Retinal Artery Occlusion. Intern med. 1996. 35:937–940.

2. Wilrentz JR, Chati Z, Krafft V, Amor M. Retinal Embolization During Carotid Angioplasty and Stenting: Mechanisms and Role of Cerebral Protection Systems. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002. 56:320–327.

3. Karjalainen K. Occlusion of the central retinal artery and retinal branch arterioles. A clinical, tonographic and fluorescein angiographic study of 175 patients. Acta Ophthalmol suppl. 1971. 109:1–95.

4. Oshinskie L. Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion and Carotid Artery Stenosis. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1987. 64:144–149.

5. Mark AR, Larry EM, Martin U. Branch retinal artery obstruction: a review of 201 eyes. Ann Ophthalmol. 1989. 21:103–107.

6. Kim IT, Park SK, Shim SD. Continued lodging of retinal emboli in a patient with internal carotid artery and opthalmic artery occlusions. Korean J Ophthalmol. 1999. 13:36–42.

7. Shin KH, Ko YI, Ko CJ. Treatment of Retinal Artery Branch Occlusion. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1982. 23:209–211.

8. Kim YT, Yoon IH, Won IG. A clinical study of 35 cases of retinal artery occlusion. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1989. 30:119–128.

9. Shimizu T, Kiyosawa M, Miura T, et al. Acute obstruction of the retinal and choroidal circulation as a complication of interventional angiography. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1993. 231:43–47.

10. Jordan WD Jr, Voellinger DC, Doblar DD, et al. Microemboli detected by transcranial Doppler monitoring in patients during carotid angioplasty versus carotid endarterectomy. Cardiovasc Surg. 1999. 7:33–38.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download