Abstract

Kimura's disease (KD) is a rare, chronic inflammatory disorder, which is characterized by tumor-like masses mainly located in the head and neck region. Extraocular muscle involvement in KD is uncommon. We report a case of KD that involved both the extraocular muscles and buccal area. A 13-year-old male presented to our clinic with a two-year history of exophthalmos of the left eye and facial swelling. Facial CT and MRI showed a 1.5 × 1.5 cm2 soft tissue mass located at the left masticator and buccal area, exophthalmos of the left eye, and diffuse thickening of the left extraocular muscles. We performed a lateral rectus muscle incisional biopsy of the left eye. Oral methylprednisolone therapy was initiated and tapered following the incisional biopsy.

Histopathologic findings of the lateral rectus muscle incisional biopsy showed abnormal vascular proliferation with marked eosinophilic infiltration in hypertrophied collagenous tissue. Post-operative histopathologic findings of the facial mass confirmed the diagnosis of KD.

Although KD with extraocular muscle involvement is uncommon, an ophthalmologist can diagnose KD by the clinical presentation of exophthalmos, eyelid swelling, and an orbital massas well as by histological examination of a biopsy of the orbital mass.

Kimura's disease (KD) was first described in 1948.1 It is one of the rare diseases that predominantly occurs in Asians, with hundreds of cases reported from China, Japan, Singapore, Indonesia, and Hong Kong under a variety of names. KD often presents with subcutaneous nodules and tumor-like masses affecting the head and neck region. KD has also been described to involve the chest wall, antecubital fossae, inguinal region, thighs, kidneys, and the median nerves.2,3 But orbital, eyelid, and lacrimal gland involvement in KD is rare.4 So far, in Korea, two cases of KD involving the orbit and eyelid have been reported, and one case of KD involving the eyelid has been reported.5,6 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of KD that involved both the extraocular muscles and buccal area.

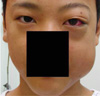

A 13-year-old Korean male was referred to our clinic with the chief complaint of a two-year history of painless exophthalmos of the left eye and facial swelling (Fig. 1). On ophthalmologic examination, the uncorrected visual acuity of his eyes was 0.5 bilaterally. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured by applanation tonometer to be 19 mmHg in both eyes. Examination of the external eyes including the eyelids and lacrimal glands showed left conjunctival hyperemia, proptosis, and no visible or palpable mass lesion.

The light reflex was normal in both eyes, and no optic nerve dysfunction was noted. An ocular motility test showed normal range of motion bilaterally without ocular discomfort, painful ophthalmoplegia, or diplopia. Hertel exophthalmometry measurements showed a 3-mm proptosis of the left eye, with measurements of 17 mm and 20 mm in the right and left eye, respectively. The fundoscopic examination was normal bilaterally.

preoperative facial CT showed a soft tissue mass at the left masseter muscle, left temporalis muscle, and left medial pterygoid muscle. A preoperative facial MRI with gadolinium enhancement revealed a 1.5×1.5 cm2 homogeneous mass with high signal intensity on T2WI and relatively well-defined margins. The mass abutted the left masseter muscle, left temporalis muscle, and left medial pterygoid muscle. Also, exophthalmos of the left eye was noted with diffuse thickening of the left extraocular muscles. However, the right eye showed no abnormal findings (Fig. 2). Blood studies documented a peripheral eosinophilia of about 26%, but the IgE level was not checked. One week following presentation, the patient underwent a lateral rectus muscle incisional biospy of the left eye to confirm the diagnosis. The histologic examination of the incisional biopsy showed abnormal vascular proliferation with marked eosinophilic infiltration in hypertrophied collagenous tissue (Fig. 3).

Following the surgery, 16 mg of oral methylprednisolone was initiated twice a day for four days. After oral steroid therapy was tapered for about two months, the exophthalmos of the left eye and facial swelling had substantially subsided (Fig. 4). However, the size of the soft tissue mass at the left buccal space increased again following steroid withdrawal. To manage the increase in mass size, the otolaryngologist performed a trans-oral facial mass excision biopsy. The post-operative histologic findings of the biopsy of the facial mass included follicular hyperplasia with perifollicular fibrosis and massive infiltration by mature eosinophils (Fig. 5), which were the same histologic findings seen in the incisional biopsy of the patient's left lateral rectus muscle.

Even though the most common location of the KD lesions are at the orbit, especially in the superior orbital space, KD is a rare diagnosis in ophthalmology. Other locations of KD lesions (in decreasing order) include the eyelid and orbit, the eyelid alone, the lacrimal gland alone, and the lacrimal gland and the eyelid. To our knowledge, this case is the first report describing KD with involvement of the extraocular muscles and buccal area.

KD occurs most commonly in young males, usually teenagers. However, patients with orbital KD tend to be older (30-50 years). The length of time prior to initial examination is typically several years, because KD lesions either gradually enlarge and increase in number over time or spontaneously regress. Clinically, KD patients present with exophthalmos, palpable orbital with or without eyelid lesions, and eyelid edema.4 Pupil reaction, tonometric and fundoscopic findings in KD patients are typically normal. The peripheral blood of KD patients usually show eosinophilia of up to 54%, whereas fewer patients show elevated serum IgE titers.7-9 In our case, exophthalmos of the left eye and diffuse thickening of the left extraocular muscles without limitation of ocular motility was noted. Our patient also presented with a mass lesion located within the buccal space. Furthermore, our patient presented with a eosinophilia of 26%, but his IgE titers were not checked.

KD lesions tend to have a low intensity signal on T1-weighted MRI and a high intensity signal on T2-weighted MRI. Heterogeneous gadolinium enhancement is a common finding in KD.10-13 However, our patient's lesions showed relatively homogeneous gadolinium enhancement on T2-weight MRI, findings which suggest a diagnosis of pseudotumor, lymphoproliferative disease, or sarcoidosis.

The differential diagnosis of KD includes angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, angiosarcoma, pyogenic granuloma, Kaposi's sarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, hamartoma, lymphoma, and an insect bite or sting.14 It is difficult to diagnose KD when it affects the extraocular muscles, as this presentation has clinically nonspecific symptoms and signs. Therefore, histopathologic findings by biopsy is necessary to help with the diagnosis.

Histologically, KD lesions are characterized by dense fibrosis, capillary proliferation, and a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate of lymphocytes, reactive lymphoid follicles, and aggregates of eosinophils. Typically, lymphocytes and lymphoid follicles with distinct germinal centers are present. Our reported case also showed the typical pathologic findings seen in KD.

The clinical course of KD without treatment is indolent. Therapies for ocular and adnexal KD include observation, excision, steroids, radiation, and chemotherapy alone or in various combinations. Hidayat et al. recommended surgery alone as the most effective treatment.14 Most of the previously reported cases of KD were successfully treated with excisional biopsy.14,15 A favorable response to corticosteroid therapy following biopsy has been reported.16 Chang and Chen support the use of radiation over excision as primary therapy and reported excellent results in 31 Chinese patients.8 Recurrence of KD frequently follows incomplete excision. Shenoy et al. reported that cyclosporine produces an excellent response in recurrent KD.17 Cyclosporine has also been reported to be effective in the treatment of KD.18 In our case, the patient was treated with an extraocular muscle incision biopsy and facial mass excision combined with postoperative oral corticosteroid therapy. Corticosteroids were effective in treating the lesions, but regrowth of the facial mass occurred following steroid withdrawal. However, our patient was lost to follow-up, and long-term results of treatment could not be evaluated.

Although KD involving the extraocular muscles is rare, ophthalmologists should consider KD when a patient presents with exophthalmos, eyelid swelling, or an orbital mass and confirm the diagnosis by histological examination of a biopsy of the orbital mass. With regard to treatment for KD, we consider corticosteroid therapy following mass excision to be a good treatment modality.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Photograph of patient's face prior to surgery showing exophthalmos of the left eye and swelling of the left upper eyelid and buccal area.

Fig. 2

T2-weighted MRI scan with enhancement showed exophthalmos of the left eye and diffuse thickening of the left extraocular muscles (A, B) and a relatively well-defined enhancing homogenous mass at the left masseter muscle, left temporalis muscle, and left medial pterygoid muscle (C).

Fig. 3

A&B, Histopathological examination of an incisional biopsy of the left lateral rectus muscle showed lymphoid cell aggregation and abnormal vascular proliferation with marked eosinophilic infiltration in hypertrophied collagenous tissue. (A: Hematoxylin & Eosin ×100, B: Hematoxylin & Eosin ×200).

References

1. Kimura T, Yoshimura S, Ishikawa E. Unusual granulation combined with hyperplastic change of lymphoid tissues. Trans Soc Pathol Jpn. 1948. 37:179–180.

2. Kung IT, Gibson JB, Bannatyne PM. Kimura's disease: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases and its distinction from angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Pathology. 1984. 16:39–44.

3. Kuo TT, Shih LY, Chan HL. Kimura's disease: Involvement of regional lymph nodes and distinction from angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988. 12:843–854.

4. Amemiya T. Eosinophilic granuloma of the soft tissue in the orbit. Ophthalmologica. 1981. 182:42–48.

5. Chung DH, Kim BJ, Kim YD. Kimura's disease involving the eyelid and orbit. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2002. 43:1789–1796.

6. Kim YH, Lee YR, Choi YH. A case of Kimura's disease of the eyelid. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2004. 45:2133–2136.

7. Googe PB, Harris NL, Mihm MC Jr. Kimura's disease and angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia: two distinct histopathological entities. J Cutan Pathol. 1987. 14:263–271.

8. Chang TL, Chen CY. Eosinophilic granuloma of lymph nodes and soft tissue. Chin Med J. 1962. 81:384–387.

9. Urabe A, Tsuneyoshi M, Enjoji M. Epithelioid hemangioma versus Kimura's disease: A comparative clinicopathologic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987. 11:758–766.

10. Ching AS, Tsang WM, Ahuja AT, Metreweli C. Extranodal manifestation of Kimura's disease Ultrasound features. Eur Radiol. 2002. 12:600–604.

11. Hiwatashi A, Hasuo K, Shiina T, et al. Kimura's disease with bilateral auricular masses. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999. 20:1976–1978.

12. Takahashi S, Ueda J, Furukawa T, et al. Kimura disease CT and MRI findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 1996. 17:382–385.

13. Aoki T, Shiiki K, Naito H, Ota Y. Cytokine levels and the effect of prednisolone on Kimura's disease Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001. 59:1238–1241.

14. Hidayat AA, Cameron JD, Font RL, Zimmerman LE. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (Kimura's disease) of the orbit and ocular adnexa. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983. 96:176–189.

15. Smith DL, Kincaid MC, Nicolitz E. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (Kimura's disease) of the orbit. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988. 106:793–795.

16. Sheren SB, Custer PL, Smith ME. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia of the orbit associated with obstructive airway disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989. 198:167–169.

17. Shenoy VV, Joshi SR, Kotwal VS, et al. Recurrent Kimura's disease: excellent response to cyclosporine. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006. 54:153–155.

18. Wang YS, Tay YK, Tan E, Poh WT. Treatment of Kimura's disease with cyclosporine. J Dermatolog Treat. 2005. 16:242–244.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download