Abstract

We report four unusual cases of upper eyelid retraction following periorbital trauma. Four previously healthy patients were evaluated for unilateral upper eyelid retraction following periorbital trauma. A 31-year-old man (Case 1) and a 24-year-old man (Case 2) presented with left upper eyelid retraction which developed after blow-out fractures, a 44-year-old woman (Case 3) presented with left upper eyelid retraction secondary to a periorbital contusion that occurred one week prior, and a 56-year-old man (Case 4) presented with left upper eyelid retraction that developed 1 month after a lower canalicular laceration was sustained during a traffic accident. The authors performed a thyroid function test and orbital computed tomography (CT) in all cases. Thyroid function was normal in all patients, CT showed an adhesion of the superior rectus muscle and superior oblique muscle in the first case and diffuse thickening of the superior rectus muscle and levator complex in the third case. CT showed no specific findings in the second or fourth cases. Upper eyelid retraction due to superior complex adhesion can be considered one of the complications of periorbital trauma.

Upper eyelid retraction is mainly caused by thyroid ophthalmopathy. Contributory factors include sympathetic overstimulation of Müller's muscle, fibrosis, shortening, and overaction of the levator complex secondary to the tethering of the inferior rectus muscle.1,2 Other common causes of eyelid retraction include neurogenic disease and pseudoretraction of the eyelid,2 the latter of which is a result of contralateral blepharoptosis, and is frequently recognized in patients with acquired ptosis associated with levator aponeurosis dehiscence or disinsertion.3 Several reports have addressed upper eyelid retraction following a blow-out fracture and ocular surgery;4-7 however, we were unable to find a report on upper eyelid retraction following periorbital contusion without fracture. Here, we report on four cases of posttraumatic upper eyelid retraction with and without blow-out fracture.

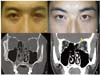

Case 1. A 31-year-old man presented with left periorbital swelling and diplopia after a blunt orbital trauma (Fig. 1A). The man reported being hit by a lump of iron at work the previous day. The patient complained of diplopia in the primary position, left gaze, and downgaze. Hertel exophthalmometry measured 17 mm OU. Initial orbital computed tomography (CT) showed a large left inferior and medial orbital wall fracture extending posteriorly (Fig. 1C), and soft tissue was found to be entrapped at the orbital floor fracture site. The patient underwent surgical repair of the medial and inferior orbital fractures. Incarcerated soft tissue was released from the fracture site and a 26×16×1 mm sized Medpor barrier sheet implant (Porex Surgical Products Group, Newnan, GA, U.S.A.) was placed over the defect. One month after surgery, the diplopia disappeared in the primary position but remained in downgaze, especially during adduction. In addition, we detected newly developed left upper eyelid retraction and lid lag on downgaze (Fig. 1B). Hertel exophthalmometry measurement was the same as before surgery. An orbital CT scan revealed adhesion between the superior rectus and superior oblique muscle (Fig. 1D). The patient was followed for 10 months and the left upper eyelid retraction persisted without improvement.

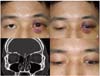

Case 2. This case was very similar to the first case, with the exception of the latent period. A 24-year-old man presented with left upper eyelid swelling and diplopia after falling down the previous day. He showed upper eyelid retraction and lid lag of the left eye (Fig. 2A, B). Orbital CT showed a large left medial wall blow-out fracture and no specific findings regarding extraocular muscles or orbital soft tissue (Fig. 2C). Ancillary tests were within normal limits. The patient underwent blow-out fracture repair with a porous implant. The surgical outcome was satisfactory without any ocular motility disorder except left upper eyelid retraction that developed at the time of trauma (Fig. 2D). The patient strongly denied preexisting upper eyelid retraction and refused a secondary orbital CT, therefore we could not pursue further evaluation of other possible causes of the eyelid retraction.

Case 3. A 44-year-old woman presented with left upper eyelid retraction following periorbital contusion one week prior to initial presentation. Upon examination we noted upper eyelid retraction with a 1 mm scleral show and a lid lag of her left eye (Fig. 3A, B). Hertel exophthalmometry showed no difference between the right and left eyes. Thyroid function testing was performed to exclude thyroid ophthalmopathy, and an orbital CT scan was performed. The thyroid function test included T3, T4, free T4, TSH, TSH receptor antibodies, and antithyroglobulin antibodies. The laboratory results were normal and CT showed mild and diffuse thickening between the left superior rectus muscle and the levator complex (Fig. 3C). She was followed for 6 months without improvement of the left upper eyelid retraction.

Case 4. A 56-year-old man visited our clinic for a left orbital contusion and lower canalicular laceration sustained in a traffic accident. His initial orbital CT scan revealed no specific findings, so the following day we repaired the canalicular laceration and inserted a Crawford tube. However, one month after surgery, even though the sutured wound was in good condition, he presented with upper eyelid retraction and a slight lid lag on the left eye (Fig. 4A, B).

Routine laboratory tests, including a thyroid function test, were normal. A second orbital CT scan with enhancement was performed, but no noticeable findings resulted, unlike in cases 1 and 3 (Fig. 4C). The patient was not overly concerned about the asymmetry of his upper eyelid. He was followed for 3 months and did not return for subsequent follow-up.

Ptosis is a common complication of orbital trauma, and is caused by damage of the levator muscle and aponeurosis.8 For that reason, upper eyelid retraction is a paradoxical response. There are few reports on posttraumatic upper eyelid retraction with latency periods ranging from several months to years.4-6 Putterman et al.4 reported upper eyelid retraction after a blow-out fracture, and hypothesized that lid retraction occurs secondary to overaction of Müller's muscle. This argument was supported by the fact that two patients were successfully treated with excision of Müller's muscle. In contrast, Conway5 reported upper eyelid retraction following a blow-out fracture of the orbit with enophthalmos and postulated that this was due to traction on the connective tissue sheath of the levator palpebrae muscle through its connective tissue interconnections with other extraocular muscles. Hatt6 also described three cases of posttraumatic upper eyelid retraction without apparent involvement of the superior rectus muscle after latency periods ranging from several months to years; however, he was uncommitted regarding the mechanism of eyelid retraction.

In our study, none of the patients had any systemic diseases and they all denied the possibility of preexisting retraction of the upper eyelid prior to trauma. If upper eyelid retraction is caused by overstimulation of the superior rectus and levator, lid lag should improve in downgaze, when innervation to these muscles is minimal.5 In our reported cases, patients had constant lid retraction in all fields of gaze and a significant lid lag in downgaze. These observations suggest a mechanical cause for lid retraction rather than a neuromuscular cause, such as levator overaction. Because thyroid eye disease may occur in the absence of clinical or biochemical evidence of thyroid dysfunction, thyroid orbitopathy cannot be easily excluded.9 However, sudden onset immediately after trauma and only affecting the traumatized eye support the role of adhesion rather than thyroid orbitopathy as the underlying mechanism of eyelid retraction.

In the first case, the patient complained of diplopia during downgaze and adduction. Since no limitation was noted at elevation and we relieved all of the incarcerated soft tissue during surgery, this diplopia may have been induced by involvement of the superior oblique muscle, as indicated by the CT scan (Fig. 1D). This hypothesis is similar to that proposed by Conway,5 who suggested that upper eyelid retraction is brought on by adhesion of the levator complex to adjacent connective tissue after a blow-out fracture. In the last two cases of our study, upper eyelid retractions were present without fractures. In case 3, considering the patient's history of trauma, we believe that an organizing hematoma or granulation tissue caused an adhesion to form around the levator complex, and this adhesion contributed to the upper eyelid retraction. In case 4, CT and laboratory tests showed no abnormalities, and we speculate that a slight adhesion not visualized by CT might have caused the upper eyelid retraction.

Cases 2 and 3 complained of eyelid retraction immediately after periorbital contusion without any latency periods. Case 2 especially differs from those previously described as there was no fracture or latency period. Conway5 reported lid retraction 2 months after a blow-out fracture and Hatt6 stated that it took several months to years before lid retraction occurs following periorbital trauma. In our study, it took one to two months to show lid retraction after trauma in the first and fourth cases, but retraction was immediate in cases 2 and 3. We are unable to propose a mechanism underlying this latency, but our cases demonstrate that it can vary greatly. Thus, when taking a history in a patient with upper eyelid retraction, a protracted trauma history should be considered.

Eyelid retraction persisted until recent follow-up in all four cases. Case 3 is very concerned about the eyelid retraction, and cosmetic surgery will be undertaken in the absence of improvement over the next 6 months.

In summary, eyelid retraction due to superior complex adhesion can occur after orbital trauma, and should be considered one of the complications of trauma. Moreover, adhesions that cause eyelid retraction are likely to be visualized by CT, but they may not be observed in all cases.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Case 1: (A) At his visit he showed mild swelling and bruising in the left eyelid, but no retraction was noted. (B) Left upper eyelid retraction developed one month after blow-out fracture repair. (C) CT scan showing a large left medial and inferior wall fracture and soft tissue incarceration. (D) One month after blow-out fracture repair, this CT scan revealed adhesion between the superior rectus and superior oblique muscles (arrow). |

| Fig. 2Case 2: (A) At his visit he showed swelling, bruising and retraction in the left eyelid. (B) Significant lid lag on downgaze in the left eye. (C, D) Eyelid retraction and lid lag persisted in the left eye one month after blow-out fracture repair. |

References

1. Hwang JM, Kim WB. Etiology of eyelid retraction in Koreans. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1998. 39:1069–1076.

2. Bartley GB. The differential diagnosis and classification of eyelid retraction. Ophthalmology. 1996. 103:168–176.

3. Meyer DR, Wobig JL. Detection of contralateral eyelid retraction associated with blepharoptosis. Ophthalmology. 1992. 99:366–375.

4. Putterman AM, Urist MJ. Upper eyelid retraction after blowout fracture. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976. 94:112–116.

5. Conway ST. Lid retraction following blow-out fracture of the orbit. Ophthalmic Surg. 1988. 19:279–281.

6. Hatt M. Post-traumatic upper eyelid retraction. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1985. 186:217–219.

7. Mauriello JA Jr, Palydowycz SB. Upper eyelid retraction after retinal detachment repair. Ophthalmic Surg. 1993. 24:694–697.

8. Finsterer J. Ptosis: Causes, presentation, and management. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003. 27:193–204.

9. Bartley GB, Gorman CA. Diagnostic criteria for Graves' ophthalmopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995. 119:792–795.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download