Abstract

Methods

A 60-year-old woman presented for removal of an itchy subconjunctival mass in her left eye. Her ocular findings were normal, except for a subconjunctival mass (1.5×1.5 mm).

The subconjunctival sparganosis is rare tissue helminthiasis which developed frequently in abdominal, urethral and vertebral cases. The first case of ocular sparganosis in Korea was reported in 2002, and five cases have been reported worldwide. Of these, two cases were found under the conjunctiva.1-3 We report the first Korean case of ocular sparganosis, which manifested as a subconjunctival mass and live form.

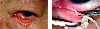

A 60-year-old woman was admitted complaining of an itching sensation in the medial conjunctiva of the left eye, for several months. At the initial examination, her visual acuity was 20/20, and the intraocular pressure was 16 mm Hg in each eye. Slit-lamp examination showed mild lens opacity in both eyes. A 1.5×1.5 cm sized, tender and yellowish mass was detected in the nasal conjunctiva of the left eye. Despite treatment with systemic antibiotics and anti-inflammatory agents for several months at another eye clinic, the patient continued to complain of intermittent symptoms. The mass was excised under a slit lamp (Fig. 1A, Fig. 1B). On excision, a white, flat, wrinkled, thread-like worm, 11 cm in length, was found in the nasal subconjunctiva of the left eye (Fig. 2).

On microscopic examination, it was a larva and a foreign body granulomatous reaction was seen in soft tissue. A section of worm had a non-cellular tegument, subtegumental cells, and parenchyma containing calcareous corpuscles and longitudinal smooth muscle fibers, which confirmed as a sparganum larva (Fig. 3).

Serodiagnosis using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay revealed increased titer of Sparganum specific IgG (1.51). The patient ate several snakes or frogs 20 years ago, and she she drank water from mountain springs for 6 months.

Three days after the excision, surgery was performed to find the scolex. But there was no scolex. Given its rarity and the considerable variation in the manifestations, it is difficult to diagnose and differentiate sparganosis from a wide variety of inflammatory and neoplastic disorders.

Human can serve as the intermediate host for several species of cestodes. For example, infections with Taenia spp. cause cysticercosis, and Echinococcus spp. cause hydatid disease.4 Human can also serve as the secondary intermediate host for some cestodes belonging to the order Pseudophyllidea. In these cases, sparganum, the metacestode stage of cestodes, which is known as a plerocercoid is infected and results sparganosis.4,5 Sparganosis is a zoonosis contracted from amphibians, reptiles, or mammals, and occurs occasionally in humans. The infection has been reported in many countries but is most common in eastern Asia.6

After ingestion by a human, the sparganum larvae migrate through the viscera and can end up in many different tissues, where they grow. Ocular sparganosis is the most common presentation found in Korea. A mass lesion is the most common clinical sign.7

The early symptom of subconjunctival sparoganosis is similar to that of asymptomatic subconjunctival mass, allergic conjunctivitis, or blepharitis. And the patient might be suffered from pain, epiphora, chemosis, and ptosis. In addition to these of symptoms, subconjunctival sparganosis can cause similar symptom of orbital cellulitis, exophthalmos, and expose cornea ulcer. If the worm invades orbit, it lead to severe inflammation or blindness.8

Human ocular sparganosis is a surgical disease because its diagnosis depends almost entirely on the demonstration of larva from the lesion.

However, these informations have not always been helpful for correct diagnosis, because human sparganosis show great variations in the manifestation. In the differential diagnosis of human sparganosis, we must take into consideration trematodes, which present a thinner tegument without folds besides having genital organs and an alimentary canal, and the larval forms of other cestodes such as cysticercus, coenurus and hydatid. These, having a cystic wall, a scolex, a rostellum, suckers or hooks, are usually easily recognizable.

The diagnosis is usually confirmed by postoperative histological examination. The immunologic serodiagnosis of sparganosis, using indirect immunofluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, is helpful. No medication has proven effective against sparganum, and the principal therapy is surgical removal.

In conclusion, although its rarity, parasitic disease should be suspected in a palpable subconjunctival mass unresponsive to the medical treatment.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Kim SH, Park K, Lee ES. Three cases of cutaneous sparganosis. Int J Dermatol. 2001. 40:656–658.

2. Griffin MP, Tompkins KJ, Ryan MT. Cutaneous sparganosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996. 18:70–72.

3. Suh Y, Choi YC, Choi YK. A Case of Ocular Sparganosis in Korea. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2002. 43:913–916.

4. Andersen K.L.. Description of musculature differences in spargana of Spirometra (Cestoda; Pseudophyllidea) and tetrathyridia of Mesocestoides (Cestoda; Cyclophyllidea) and their value in identification. J Helminthol. 1983. 57:331–334.

5. Cho SY, Kang SY, Kong Y. Purification of antigenic protein of sparganum by immunoaffinity chromatography using a monoclonal antibody. Korean J Parasitol. 1990. 280:135–142.

6. Park HY, Lee SU, Kim SH, et al. Epidemiological significance of sero-positive inhabitants against sparganum in Kangwon-do, Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2001. 42:371–374.

7. Norman S.H., Kreutner A. Jr. Sparganosis: clinical and pathologic in ten Case. South Med J. 1980. 73:297–300.

8. Sen DK, Muller R, Gupta VP, Chilana JS. Cestode Larva (Sparganum) in the anterior chamber of the eye. Trop Geogr Med. 1989. 41:270–273.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download