Abstract

Methods

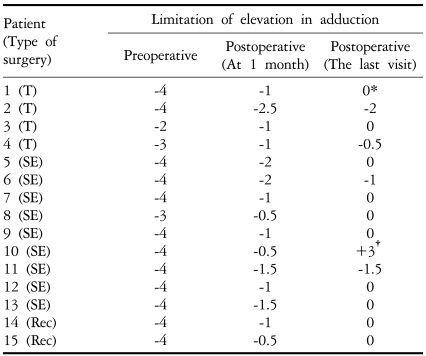

We reviewed the charts of 15 patients who underwent surgery for Brown syndrome. The limitation of elevation in adduction (LEA) ranged from -2 to -4 degrees. A superior oblique muscle (SO) tenotomy was performed in 4 patients, a silicone expander was inserted in the SO of 9 patients, and a SO recession was performed in 2 patients. The results of surgery were analyzed with a follow-up period of more than 6 months, 42.3±48.42 months on average.

Results

Nine female patients and 6 male patients with unilateral Brown syndrome were selected for this study. The left eye was the affected eye in 9 patients. The degree of preoperative LEA was -2 to -4 in 4 patients in whom SO tenotomy was performed, -3 to -4 in 9 patients treated with the silicone expander, and -2 to -4 in 2 patients treated with SO recession. The LEA was released after surgery in all patients without postoperative adhesion. However, unilateral overaction of the inferior oblique muscle due to excessive weakening of the SO occurred in 1 patient with tenotomy (25%) and in 1 patient with insertion of a silicone expander (11%).

Brown syndrome is an ocular motility disorder characterized by a limitation of elevation in adduction (LEA), which was first described by Brown in 1950. Severe mechanical restriction is present during attempts to elevate the adducted eye passively in the forced duction test (FDT), but the elevation in abduction is normal.1

The true syndrome includes only those patients who have a congenitally short anterior tendon sheath of superior oblique muscle (SO). A simulated sheath syndrome with identical clinical features may be caused by other factors such as anomalies of the tendon itself or of the trochlea, and includes all acquired cases.2

Management is dependent on cause, and includes both surgical and medical treatment. Spontaneous resolution may occur without any treatment. Surgery is performed when the patient has strabismus or abnormal head posture. The procedure is based on the weakening or the lengthening of the SO.3

Complete tenectomy of the SO was advocated by Jacobi4 and by Crawford.5 Crawford5 proposed a z-tenotomy of SO. The tenotomy that preserved the posterior capsule of the SO was designed by Parks.6 However, overaction of the inferior oblique muscle (IOOA) frequently occurs following a tenotomy or tenectomy of SO. in 1987, Parks and Eustis7 proposed a combined procedure of SO tenotomy with simultaneous IO recession. In 1991, Wright8 reported the effectiveness of a procedure involving insertion of a silicone expander. Graduated recession of the SO was proposed by Calderia9 in 1975 as a procedure for A pattern with SOOA. This is another SO weakening procedure and can be used for the purpose of correcting Brown syndrome.

In this study, we retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of surgery for Brown syndrome.

This study enrolled 15 patients that had been diagnosed with Brown syndrome and subsequently underwent weakening or lengthening surgery of the SO muscle, as indicated by strabismus or abnormal head posture. These patients exhibited a limitation of active elevation in adduction and a severe restriction in elevating the adducted eye with FDT. The angle of deviation was described by prism diopters or degrees by alternate prism cover testing. We used prisms or prisms being converted to the degree.

Three different procedures were used to correct LEA. SO tenotomy was performed in 4 patients, keeping the posterior capsule of the SO intact, following Parks' approach.6 In 9 patients, a silicone expander using a 240 retinal band was inserted into the SO after a transection of the SO tendon. It was made at the nasal side of the superior rectus muscle (SR), following Wright's procedure.8 The release of the LEA was confirmed with FDT. The silicone expander was presoaked in a gentamicin solution and cut into the desired length, ranging from 5.5 to 7 mm. It was sewn between the cut ends of the tendon.

SO recession was performed according to the method devised by Kaufmann.10 A superior-temporal quadrant incision was made 8mm from the limbus, and the SO tendon was isolated at the temporal side of the SR. After detachment, the SO was passed under the SR and recessed 8.5 mm in one patient. The other patient underwent an 8-mm recession, combined with a 5-mm loop suture, using 5-0 Mersilene.

The patients' charts were reviewed retrospectively. Visual acuity, ocular motility, angle of deviation, refractive error, sensorial function, and fundus were evaluated. We selected one of the procedures for each patient without any inclusion criteria.

The LEA was graded from 0 to 4. Improvement after surgery was defined as a reduction of vertical deviation and release of the LEA. The period of postoperative follow-up was more than 6 months (42.7±48.42 months on average).

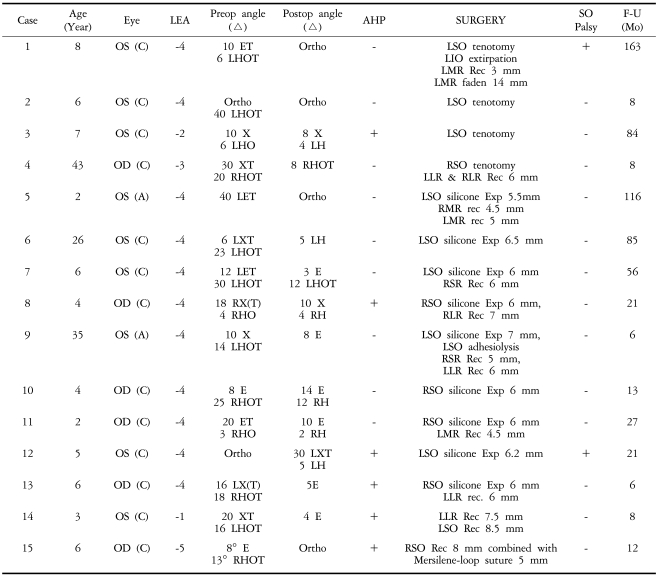

The causes of Brown syndrome were congenital in 13 patients and acquired in 2 patients. The acquired causes included both idiopathic causes and those secondary to the tucking of the SO in acquired SO palsy. Nine of the 15 patients were female. The left eye was involved in 9 of the 15 patients. There were no bilateral cases. Preoperatively, the amount of vertical deviation was 14.53±11.73 (0-40) prism diopters (PD), and the horizontal deviation was 13.86±10.70 PD (0-40). The mean duration of follow-up was 42.26±48.42 months, ranging from 6 to 163 months (Table 1).

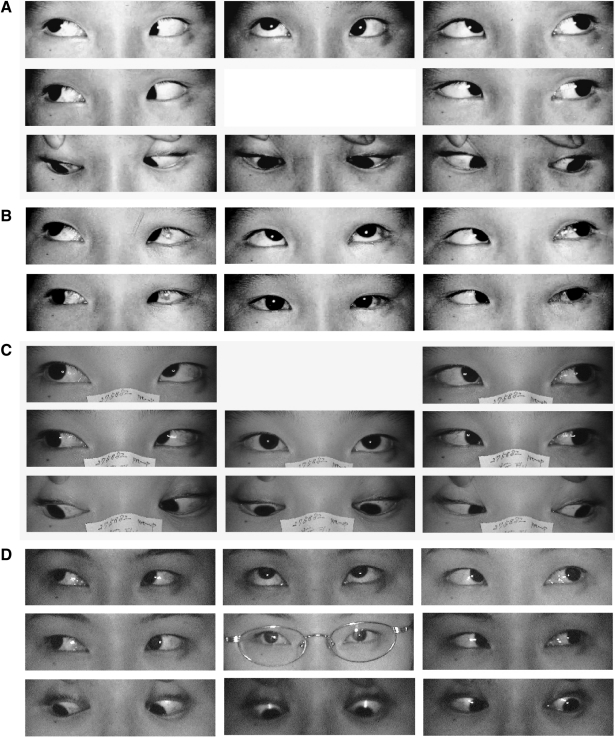

After tenotomy, the amount of vertical deviation improved from 18.0±16.08 PD preoperatively to 3.0±3.82 PD postoperatively. The preoperative LEA was from -2 to -4 degrees. One of 4 patients showed a complete elevation in adduction and 2 patients improved to -0.5 and -2 degrees of LEA, respectively (Table 2). Another patient showed +1 IOOA 2.5 years after surgery, which gradually increased to +3 IOOA after 6 years. Ipsilateral extirpation of the IO without denervation was performed (Fig. 1).

In the silicone expander group, the amount of vertical deviation improved from 13.0±11.6 PD preoperatively to 4.4±4.74 PD postoperatively. The LEA was from -3 to -4 degrees. After insertion of the silicone expander, 6 patients showed complete recovery, and 2 patients demonstrated some improvement to -1.5 ~ -1.0 degrees. Ipsilateral SO underaction (UA) and inferior oblique overaction (IOOA) developed in one patient one year after surgery. Postoperatively, initial mild under-correction appeared in all the patients. This disappeared after frequently moving the eye to the nasal-up direction in 6 patients. No evidence of adhesion was present after insertion of the silicone expander.

One patient underwent recession of the SO alone. In another patient, SO recession was performed combined with a 5-mm Mersilene loop suture to lengthen the SO tendon to 13mm. In these two patients, the preoperative hypotropia (HOT) in the involved eye was 16 PD and 13° in each patient. After SO recession, they showed no hypotropia.

Case 1. An 8-year-old girl presented with limitation of upward gaze of the left eye movement on August 7th, 1985. Examination revealed an inability to elevate the left eye in adduction (-4 grade) and in primary gaze. Abduction was normal. Movement of the right eye was normal. Best-corrected visual acuity was 1.0 in the right eye and 0.3 in the left eye. The refractive error was +0.25 + 0.50 × 90° in the right eye and -0.25 + 1.00 × 90° in the left eye. In the primary gaze, she presented with 10PD esotropia (ET) and 6PD HOT in the left eye at distance, and 35PD ET' and 6PD HOT' at near. A diagnosis of Brown's syndrome and accommodative esotropia was made. Bifocal glasses were prescribed and patching on the right eye was used to correct amblyopia of the left eye.

LEA (-4) was confirmed by FDT under general anesthesia and a SO tenotomy was performed in the left eye by one of the authors (YAC). The LEA was eliminated and normal ocular rotation was observed. The patient was lost to follow-up after surgery. Three years after surgery, esotropia of 20PD was found with ipsilateral IOOA +1. IOOA was gradually aggravated to +3 in the follow-up. SOUA (-1.5) was also shown. Seven years after the operation, the visual acuity in the left eye was 0.05 due to lack of follow-up checking. Then, 3-mm recession of the medial rectus muscle (MR) and IO extirpation without denervation were performed in the left eye. Nine years later, the 14-mm Faden operation on the MR was performed in the same eye. The eyes were orthophoric at the follow-up of 14 years (Fig. 1).

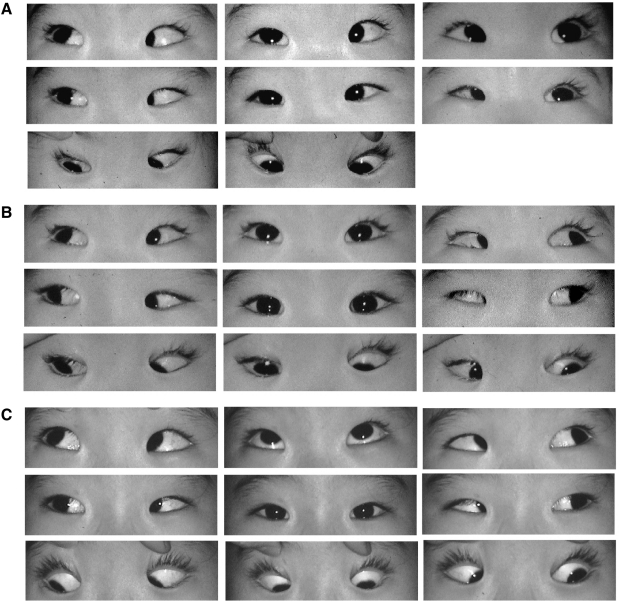

Case 5. A 20-month-old female presented with LEA in the left eye. In the primary gaze, she had 40PD ET at distance and 40PD ET 10PD HOT at near. Version revealed a -4 inability to elevate the left eye both in adduction and primary gaze. She was diagnosed with Brown's syndrome with esotropia. Her visual fixation was good, central and maintained (GCM) in each eye.

LEA -4 in the left eye was confirmed under general anesthesia at the time of surgery. Insertion of a 5.5mm silicone expander in the left eye and recession of the MR in both eyes (4.5mm in the right eye and 5mm in the left eye) were performed by YAC. Four months after surgery, -2 LEA remained with orothophoria in the primary gaze. However, the limitation was completely relieved to normal elevation on adduction (Fig. 2).

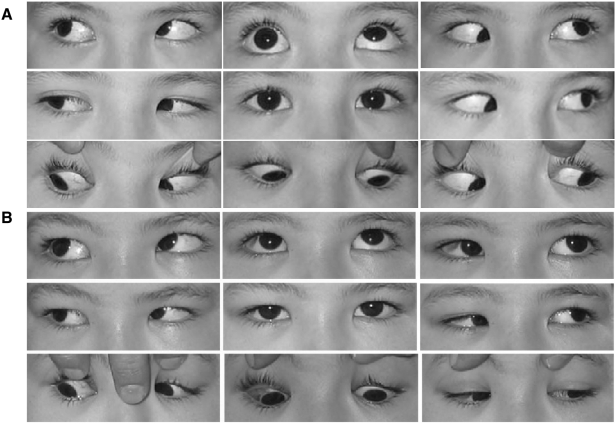

Case 15. A six-year-old boy had -4 LEA and -4 limitation of elevation in the primary gaze of the right eye. He also demonstrated eight degrees of esophoria with 13° of HOT in primary gaze, and he preferred 10 degrees of left head-turning. FDT revealed severe (-4) LEA of the left eye at the time of surgery. Eight mm of recession of the SO combined with a 5-mm Mersilene loop-suture was performed by MG to lengthen SO by 13mm. By one day after surgery, the LEA had disappeared and normal ocular movement was obtained in all gazes (Fig. 3). At 8 months postoperatively, he showed an orthophoria in primary gaze both at distance and near with 0-5° of head turn, and 15° of elevation in adduction.

For conditions involving SO weakening or lengthening, surgical corrections include tenotomy, tenectomy, recession, split lengthening, z-tenotomy, and SO recession.4-10 These procedures cause slackening of the SO tendon complex, but have with inconsistent results.

SO tenotomy is one of the most popular surgeries. Its major advantage is that it is easier and faster than other SO weakening procedures. It has proved to be successful in relieving LEA, but the results are not predictable in all situations because IOOA frequently follows.11 After the tendon is cut, the ends are released and are free to separate, despite the intact posterior part of the muscle capsule. Tendon separation is hard to control and can lead to variable results. If the cut ends separate widely, SO palsy may occur and IOOA may follow gradually. In an SO tenotomy nasal to the SR, the cut ends of the tendon may scar the sclera, creating a new insertion at the nasal border of the SR. This problem can be minimized by carefully preserving the intermuscular septum along the nasal border of the SR.8,12 If the two muscle reunite or are close together, under-correction results.13 Therefore an SO tenotomy can be dangerous in patients with bifoveal fusion or with cyclovertical diplopia.14.15 This is an especially difficult problem, since the ends of the tendon are hard to find, making the tenotomy procedure difficult to reverse. The possibility of iatrogenic SO palsy increases and ipsilateral IOOA frequently follows.7 Parks and Eustis7 proposed a combined procedure of SO tenotomy with simultaneous ipsilateral IO to reduce the effort of doing a second procedure.

In this study, 2 of 4 patients suffered under-action of the SO after tenotomy. An ipsilateral IO recession of 14mm was performed in one of the patients 3 years after the SO tenotomy. The other patient was lost to follow-up.

Wright8 designed a technique for inserting a silicone expander into the SO tendon, using a 240 retinal band, thus lengthening the short tendon. The surgical results were good and avoided disturbing SO insertion and adhesion. This technique has been appealing because it theoretically offers a controlled weakening of the SO tendon with the advantage of avoiding simultaneous surgery on a second muscle.8,16,17

Silicone expander insertion is a more time-consuming process than a tenotomy, however, offers the advantage of including tendon slack in a graded fashion without changing the characteristics of insertion. This procedure maintains SO function, preventing subsequent SO palsy. It also controls the amount of separation of the cut ends. The cut ends of the tendon can be retrieved, if necessary, because they are secured.

Wright et al16 reported that the incidence of post-operative SO paresis was significantly higher after a tenotomy, occurring in 30% of patients, than after the insertion of the silicone tendon expander (occurring in none of the patients). He advocated that the maximal length of the expander should be 7 mm because of the possibility of extrusion by over-lengthening.18 Residual overaction of SO can be greatly facilitated by the presence of a long silicone expander. A lower incidence of SO palsy after insertion of a silicone expander rather than a tenotomy was reported by Stager et al.19

In this study, we also inserted silicone expanders 5.5~7 mm in length, according to the severity of the LEA on FDT. IOOA caused by SO paresis was seen in only 1 patient (11%). A better result was obtained than with a tenotomy (25%IOOA).

Postoperative adhesion at the site of insertion causes under-correction and an ineffective result.8 Wilson et al.20 warned of the potential development of down-gaze restriction after this procedure. This complication may be due to adhesion to the SR or to the sclera. Surgeons should be cautious in avoiding postoperative adhesion.

Improvement of initial under-correction and over-correction continues with time.9 Therefore, long-term follow-up is encouraged. In our study, all patients experienced an initial mild underaction of the SO, which gradually improved to the normal functionally. Two patients had mild LEA at their last visit (-1~-1.5).

SO recession has the theoretical advantage of producing a graded weakening. The disadvantage is that it tends to collapse the normally broad posterior insertion of the SO tendon, thus altering the functional mechanics of the SO, although several surgeons9,10,21,22,23 report good results after SO recession.

Parks24 was concerned that the tendon fibers did not lend themselves to being sutured to the sclera easily, so that the result usually included a collapse of the tendon width. He also felt that moving the insertion site might cause an additional problem with cyclotorsion, although none was documented in the series. In a tenotomy, the broad posterior insertion of the tendon is preserved and maintains the functional mechanics of SO as an abductor, depressor, and incyclotorter.11,25 The insertion of the SO is also not disturbed during silicone-expander surgery.

Buckley22 suggested that unilateral recession enjoyed an advantage over tenotomy because recession allows for a controlled amount of weakening and the location of the tendon is known in the event that a reoperation is necessary. Our two patients also obtained good surgical outcome, in which LEA was released completely without any functional disturbance observed in follow-up of more than 6 months.

We used 3 types of SO weakening or lengthening procedures in 15 patients with Brown syndrome. The difference in correction between the techniques could not be statistically ascertained because the number of patients was small. However, the 3 procedures were effective in our patients although our results recommend more caution in avoiding SO paresis after performing a tenotomy or inserting a silicone expander. Two patients with SO recession did not have any complications after surgery.

Each procedure has its advantages. However, a surgical outcome may vary according to the particular cause of Brown syndrome and the surgeon's technique. Further study with a greater number of patients is needed.

References

1. Brown HW. Allen JH, editor. Congenital structural muscle anomalies. Strabismus Ophthalmic Symposium. 1950. St. Louis: Mosby;p. 205.

2. Brown HW. True and simulated superior oblique tendon sheath syndromes. Doc Ophthalmol. 1973; 34:123–136. PMID: 4706084.

3. Von noorden GK, Campos EC. Binocular Vision and Ocular Motility. 2002. 6th ed. St.Louis: Mosby;p. 466–471.

4. Jacobi KW. Tenectomy of the superior oblique in the tendon sheath syndrome (Brown). Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1972; 160:669–674. PMID: 4662719.

5. Crawford JS. Surgical treatment of true Brown's syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976; 81:289–295. PMID: 1258952.

6. Parks MM. Ocular Motility and Strabismus. 1975. Hagerstown: Harper & Row;p. 147.

7. Parks MM, Eustis HS. Simultaneous superior oblique tenotomy and inferior oblique recession in Brown's syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1987; 94:1043–1047. PMID: 3658365.

8. Wright KW. Superior oblique silicone expander for Brown syndrome and superior oblique overaction. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1991; 28:101–107. PMID: 2051286.

9. Caldeira JA. Bilateral recession of the superior oblique in "A" pattern tropias. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1978; 15:306–311.

10. Von Kaufmann H. Strabismus. 2003. 3rd ed. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag;p. 510.

11. Parks MM. Surgery for Brown syndrome. Symposium on Strabismus, Transactions of the New Orleans Academy of Ophthalmology. 1978. St Louis: Mosby;p. 157–177.

12. Parks MM. Atlas of Strabismus Surgery. 1983. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Harper & Row;p. 190–195.

13. Prieto-Diaz J. Superior oblique overaction. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1989; 29:43–50. PMID: 2645237.

14. Reynolds JD, Wackerhagen MV. Bilateral superior oblique tenotomy for A-pattern strabismus in patients with fusion. Binocular Vision. 1988; 3:33–38.

15. Parks MM. Commentary on "Bilateral superior oblique tenotomy for A-pattern strabismus in patients with fusion". Binocular Vision. 1988; 3:39.

16. Wright KW, Min BM, Park C. Comparison of superior oblique tendon expander to superior oblique tenotomy for the management of superior oblique overaction and Brown syndrome. J Pediatric Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1992; 29:92–97.

17. Wright KW. Wright KW, editor. Superior oblique tendon silicon expander in strabismus. Color Atlas of Ophthalmic Surgery Strabismus. 1991. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott;chap. 12.

18. Wright KW. Results of the superior oblique tendon elongation procedure for severe brown's syndrome. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2000; 98:41–48. PMID: 11190035.

19. Stager DR Jr, Parks MM, Stager DR Sr, Pesheva M. Long-term results of silicone expander for moderate and severe Brown syndrome (Brown syndrome "plus"). J AAPOS. 1999; 3:328–332. PMID: 10613574.

20. Wilson ME, Sinatra RB, Saunders RA. Downgaze restriction after placement of superior oblique tendon spacer for Brown syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1995; 32:29–34. PMID: 7752031.

21. Romano P, Roholt P. Measured graduated recession of the superior oblique muscle. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1983; 20:134–140. PMID: 6350556.

22. Buckley EG, Flynn JT. Superior oblique recession versus tenotomy: a comparison of surgical results. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1983; 20:112–117. PMID: 6864426.

23. Gräf M, Kloss S, Kaufmann H. Results of surgery for congenital Brown's syndrome. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 2005; 223:630–637.

24. Parks MM. The superior oblique tendon. 33rd Doyne memorial lecture. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U.K. 1977; 97:288–304. PMID: 345531.

25. Parks MM. Management of overaction superior oblique muscles. Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, Transactions of the New Orleans Academy of Ophthalmology. 1986. New York: Raven Press;p. 409–418.

Fig. 1

Case 1. (A) Before surgery. This patient experienced -4 limitation of upward movement of the left eye in adduction and up-gaze. Elevation in abduction was normal. The movement of the right eye was normal. She presented with 10 PD ET and 6PD LHOT at distance and 35PD ET' and 6PD LHOT' at near primary gaze. A diagnosis of Brown's syndrome and accommodative esotropia with high AC/A ratio was made.

(B) FDT at surgery revealed -4 limitation of elevation in adduction and -3 limitation in upgaze of the left eye. SO tenotomy was performed in the left eye. After SO tenotomy, LEA was eliminated and normal ocular rotation was obtained on postoperative day 1.

(C) Seven years after tenotomy. Ipsilateral overaction of the IO (+3) and SO underaction (-1.5) developed with 20PD of esotropia. A 3-mm recession of the MR and IO extirpation without denervation were performed in the left eye.

(D) After the 2nd operation. Upward and downward movement in adduction of the left eye were normal. Esotropia of 8PD was seen in the primary gaze.

Fig. 2

Case 5. (A) Befor surgery. A 20-month-old female presented with limitation of the left eye in adduction (LEA) with esotropia of 40PD. She also experienced an inability to elevate the left eye in adduction and primary gaze. A forced duction test revealed -4 LEA.

(B) After surgy. Insertion of a 5.5-mm silicone expander in the SO muscle of the left eye, a 4.5-mm recession of the right medial rectus and a 5-mm recession of the left medial rectus were performed. Orthophoria was obtained in primary gaze with -1 LEA in the left eye.

(C) Five years and four months after operation, LEA was completely relieved. The patient obtained orthophoria in all gazes.

Fig. 3

Case 15. (A) Before surgery. The six-year-old boy had -4 limitation of elevation in adduction (LEA) and -4 limitation of elevation in the primary gaze of the right eye. He had 8° esophoria and 13° hypotropia of the right eye. He preferred left head turning of 10°.

(B) After surgery. LEA -4 was confirmed by a forced duction test at the time of surgery. Recession of 8 mm of the SO, combined with a 5-mm Mersilene loop-suture was performed to lengthen the tendon of the SO by 13-mm. One day after surgery, the LEA had disappeared and normal ocular movement was obtained in all gazes.

Table 1

Patient Characteristics

Preop: Preoperative, Postop: Postoperative, LEA: Limitation of elevation in adduction, AHD: Abnormal head posture, SO: Superior oblique muscle, F-U: Follow-up, C: Congenital, A: Acquired, ET: Esotropia, E: Esophoria, XT: Exotropia, X: Exophoria, RHOT: Right hypotropia, LHOT: Left hypotropia, LHO: Left hypophoria, RHO: Right hyophoria, Exp: Expander, Rec: Recession, Mo: Month.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download