Abstract

Purpose

We present a case of orbital abscess following porous orbital implant infection in a 73-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis.

Methods

Just one month after a seemingly uncomplicated enucleation and porous polyethylene (Medpor®) orbital implant surgery, implant exposure developed with profuse pus discharge. The patient was unresponsive to implant removal and MRI confirmed the presence of an orbital pus pocket. Despite extirpation of the four rectus muscles, inflammatory granulation debridement and abscess drainage, another new pus pocket developed.

Infected porous orbital implants are, to date, rare. When they occur, implant removal has been the only successful treatment modality.1,2 Several cases of porous implant infection have shown that removal of the implant did not worsen the progression of orbital infection.3,4 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of orbital implant infection not controlled with implant removal.

A 73-year-old woman presented with purulent conjunctival discharge and pain in her left, enucleated eye. She had a medical history of oral steroid intake for rheumatoid arthritis and antihypertensive medication for several years. She had an ocular history of melting necrotizing scleritis, and it was so intractable that an enucleation had been performed a month previously. After enucleation, a synthetic porous polyethylene implant (Medpor®, POREX Surgical Inc., USA, 20 mm in diameter) wrapped with sterilized donor sclera was used to replace orbital volume.

A culture of the eye discharge revealed Propionibacterium acne, at which time systemic and topical antibiotic medication was started. Despite massive antibiotic treatment, the discharge was still seen from the conjunctival wound, and the infection continued to melt the conjunctiva and wrapping donor sclera. The Medpor® implant was eventually exposed a month after implantation. The patient was diagnosed with implant infection and underwent an implant removal.

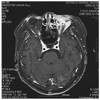

The wound seemed to recover well, but two months later, purulent discharge was again seen from the wound site. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left orbit revealed myositis of the four rectus muscles, inflammatory granulations, and abscesses around the orbit, especially around the optic nerve (Fig. 1). Extirpation of the four rectus muscles, removal of underlying inflammatory granulation, and abscess drainage were performed, and the wound was then soaked with betadine and antibiotic solution.

The wound recovered well, and a month after abscess excision, dermo-fat tissue harvested from the inguinal area was grafted to orbital defect site. The, graft failed to survive, and pus discharge from the wound developed once again. The graft was removed a month after implantation, but the discharge persisted (Fig. 2).

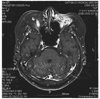

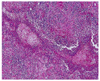

Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging two months after removal of the dermo-fat graft showed inflammatory granulations and abscess formation in the left orbit (Fig. 3). Out of concern that the inflammation might spread to the brain, we performed a partial exenteration of the left orbit. In this procedure, the skin and orbicularis muscle were dissected and removed, and tissue in the orbital apex was taken out of the socket (Fig. 4). Microscopic examination of the exenterated tissue around the abscess revealed massive inflammation, but no bacterial growth was identified in the specimen (Fig. 5). Thereafter, the wound healed well without any additional inflammation. One and one half years after the final surgery, the wound site was well resolved, and no infection or inflammation was found (Fig. 6).

Although implant exposure is the most common of the complications reported with various porous orbital implants,5,6 implant infection is the most serious because antibiotics are often ineffective, and removal may be necessary.3,6 Not only is implant removal traumatizing and destructive to the socket tissues, the additional intraconal surgery introduces the risk of damage to the extraocular muscles and their nerve supply. Exenteration also eliminates the main advantage of the porous orbital implant, that is, the potential for improved implant and prosthesis motility, especially when the improved implant is coupled with the orbital implant through a peg coupling system.5 Implant infection can often be resolved by implant removal. Organisms within a biofilm are difficult to eradicate by conventional antimicrobial therapy and can cause indolent infections. The presence of bacterial biofilms has been demonstrated on many medical devices including intravenous catheters, as well as materials relevant to the eye such as contact lenses, scleral buckles, suture materials, and intraocular lenses.7 Many ocular infections occur when such prosthetic devices come in contact with or are implanted in the eye. When orbital implants are truly infected, these biofilms render antibiotic therapy ineffective, and removal of the implant is necessary. In cases of infected hydroxyapatite orbital implants, inflammation treatment is typically successful after implant removal and additional surgical repair, such as Medpor® impalantation or dermis fat graft.8 In many cases of culture-negative presumed infection, medical antibiotic therapy was effective. This case is the first in which infection could not be controlled by removal of the orbital implant, or even by orbital exenteration including the rectus muscles.

It is unclear why surgical treatment was unsuccessful in this case. Underlying long term steroid treatment for rheumatoid arthritis might have caused greater susceptibility to infection.

This case provides further evidence that a patient who has risk factors for delayed wound-healing must be examined thoroughly when there is infection. Extreme care must be taken in planning and performing secondary surgery or, as in this case, more extensive surgery such as exenteration may be required.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1T1-weighted, gadolinium enhanced horizontal magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbits, showing myositis in all four rectus muscles, and an abscess pocket between the medial wall and medial rectus muscle (arrow). |

| Fig. 3T1 weighted, gadolinium enhanced horizontal magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbits 2 months after removal of dermo-fat graft. All four rectus muscles were removed. Previous abscess pocket was resolved, but new abscess pocket developed (arrow). |

References

1. Goldberg RA, Holds JB, Ebrahimpour J. Exposed hydroxyapatite orbital implants. Ophthalmology. 1992. 95:831–836.

2. Ainbinder DJ, Haik BG, Tellado M. Hydroxyapatitie orbital implant abscess: histopathologic correlation of an infected implant following evisceration. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994. 10:267–270.

3. Jordan DR, Brownstein S, Jolly SS. Abscessed hydroxyapatite orbital implants- a report of two cases. Ophthalmology. 1996. 103:1784–1787.

4. Oestreicher JH, Bashour M, Jong R, et al. Aspergillus Mycetoma in a secondary hydroxyapatite orbital implant - a case report and literature review. Ophthalmology. 1999. 106:987–991.

5. Kim YD, Goldberg RA, Shorr N, et al. Management of exposed hydroxyapatite orbital implants. Ophthalmology. 1994. 101:1709–1715.

6. Jordan DR, Brownstein S, Faraji H. Clinicopathologic analysis of 15 explanted hydroxyapatite implants. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004. 20:285–290.

7. Zegans ME, Becker HI, Budzik J, et al. The role of bacterial biofilms in ocular infections. DNA Cell Biol. 2002. 21:415–420.

8. You SJ, Yang HW, Lee HC, Kim SJ. 5 cases of infected hydroxyapatite orbital implant. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2002. 43:1553–1557.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download